Linne_eng

-

Upload

james-barrett -

Category

Documents

-

view

224 -

download

0

Transcript of Linne_eng

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

1/48

A

RL

LIN

N

U

by

GunnarBroberg

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

2/48

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

3/48

Carl Linnaeusby Gunnar Broberg

Swedish Institute

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

4/48

Gunnar Broberg is Professor of the History of Science

and Ideas at Lund University.

Gunnar Broberg and the Swedish InstituteNew edition e author alone is responsible for the opinions expressed

in this book.

Translation by Roger Tanner

Graphic design by BIGG, Stockholm

Cover illustration: Carl Linnaeus, painting byJ.H. Scheffel,

Paper: Cover, Tom & Otto silk g

Inside, Linn white g

Printed in Sweden by Danagrds Grafiska,

ISBN----ISBN-----

THE SWEDISH INSTITUTE (SI) is a public agency establishedto disseminate knowledge abroad about Swedens socialand cultural life, to promote cultural and informationalexchange with other countries and to contribute to in-creased international cooperation in the fields of educationand research. e Swedish Institute produces a wide range

of publications on many aspects of Swedish society. esecan be obtained directly from the Swedish Institute orfrom Swedish diplomatic missions abroad, and many areavailable on Swedens official website, www.sweden.se.

In the SWEDEN BOOKSHOP, Slottsbacken 10 in Stockholm,as well as on www.swedenbookshop.com, you will findbooks, brochures and richly illustrated gift books onSweden, a broad selection of Swedish fiction, childrensbooks and Swedish language courses. ese publications

are available in many languages.

e Swedish InstituteBox SE- StockholmSweden

Phone: +--Fax: +--E-mail: [email protected]

www.si.se

Do you have any views on this SI publication?Feel free to contact us at [email protected].

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

5/48

Contents

Preface 5The young medic and botanist 9

Everything in order: the new natural science 17Professor in Uppsala 23

Linnaeus the traveller 27The Linnaean project 33

The Apostles 37The sexual system and the binary nomenclature 43

Chronology in brief 44

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

6/48

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

7/48

ARL LINNUS (17071778) is Swedens most famous natural scientist. Heset out to list and order the whole of Creation. His importance, however,is not confined to the international history of science. In a way he is alsoa part of Swedish everyday life today, as the author of living classics whichpeople still read. e Swedes, perhaps, look on him primarily as a traveller

and explorer of their own country, while to others he is the father of themodern classification of flora and fauna. But he was much more than this.For example, he was an inspiring teacher who sent his students on voyagesof scientific discovery all over the world.C

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

8/48

6

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

9/48

7

THE MAIN CHARACTER of this publication hasa variety of names. Swedes know him asCarl von Linn, the name he took when raisedto the nobility in . In the Anglo-Saxon

world he is normally referred to as Carl

Linnaeus, which is the name he was givenat his baptism. e Latin ending of his sur-name indicates academic status, without

which he would have been called Carl Nilsson,after his father. (On one occasion Linnaeusstyled himself Carl Nelin, a cryptonym ofCarl N/ilsson/ Linn. at was in a prizecompetition, which he failed to win eventhough the alias probably deceived no-one.)en again, Linnaeus has been calledPrinceps botanicorum, the Prince of Botanists,e Pliny of the North, e Second Adamand other names besides. To present-daybotanists and zoologists who concern them-selves with matters of taxonomy, he is justplain L., the letter which indicates thenaming of an outstandingly large number

of important organisms.

A Swedish proverb says that a loved childhas many names. Perhaps the same goes foran important person, and it was certainlyno common occurrence for a scientist andprofessor to be elevated to the nobility.

Not many scientists were accorded equalityof status with Pliny, the great natural historianof antiquity. And of course it was grander stillto compare Linnaeus with the ruler ofParadise and the first namer of animals.ousands of plants and animals remind us ofthe person who named them, and innumerablegarlands of flowers have been tied in honourof Linnaeus. Every Swedish province has itsemblematic flower, and the Twinflower,provincial emblem of Smland, is calledLinnaea after the great son of that province,putting all Swedes in mind of him personally.Not until the Earth once more lies emptyand desolate will the name of Linnaeus beforgotten.

THE PRINCE OF BOTANISTS, THE PLINYOF THE NORTH, THE SECOND ADAM, L.

Linnaeus coat of arms. He was ennobledin 1757.

OPPOSITE PAGE

Cowslips on the Baltic island of landto which Linnaeus made one of his famous

journeys in 1741.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

10/48

8

Linnaeus made rather a big thing of his hum-ble origins. A great man can step forth froma small hovel, he wrote in one of his autobio-graphies. (He wrote no less than four of them,

which is usually quoted as evidence of his

self-infatuation, but that is not really fairbecause the biographies are more in the natureof curricula vitae and memoranda for subse-quent memorial addresses. is also explains

why Linnaeus writes them in the third personand not subjectively. And when he lists hisexploits this is perfectly in order, because they

were many and irrefutable.)

However charming and uncomplicated hemight seem, he was supremely career-minded.is, however, is to moralise, and as a historianone ought rather to emphasise the social mo-bility so typical of Swedish society at the time.Linnaeus grandfather was a peasant, his fatherentered the Church, he himself became a phys-ician and eventually a professor and a member

of the nobility. One could scarcely advance

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

11/48

9

any further than that. Sweden was a relativelyopen society whose agrarian population wastraditionally endowed with strength andliberty.

rough the centuries, the culture of theparsonage has been the backbone of scienceand the arts in Sweden. is is due to the closeconnection between Church and State inSweden during the th century, knownin Swedish as the Age of Greatness.e Lutheran Church was indispensable tothe State as an educator of the peasant popu-lation in peacetime and as a shepherd of soulsin the great wars of the period. e glory andthe misery of the time demanded moral fibre.

When the bubble burst, with the death ofCharles XII on his Norwegian campaign in, the established Church remained topilot the country into the more pacificand culturally fertile Age of Liberty.

The young medic and botanist

LINNUS HIMSELF MAINTAINED that he was pre-disposed for botany by growing up in a beauti-ful part of Sweden, Smland, as the son of akeen botanist. e fact of his being born just

when spring was at its loveliest and the cuckoowas proclaiming summer was in itself an augu-ry of the scientific flowering that was to follow.His father had created a small garden contain-ing many unusual plants which he appreciatedmore for their beauty than for their utility.

And during her pregnancy, his mother couldfeast her eyes on it, so that Linnaeus becamea botanist while still in the womb. Subsequentbiographers have elaborated the theme ofLinnaeus mother, Christina Brodersonia, deco-rating his cradle with flowers. All this, coupled

with his humble origins, has been turned intoan edifying national saga, with Linnaeus asthe embodiment of an impoverished, exhaustedsmall nation rising to maturity, power andauthority. e saga of Linnaeus is one of the

highlights of Swedens national mythology.

LINNUS BECAME A BOTANISTWHILE STILL IN THE WOMB

OPPOSITE PAGE

The 32-year-old Linnaeus in his wedding finery.

Oil painting by J. H. Scheffel, 1739.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

12/48

10

Born at Rshult in , Linnaeus was theeldest son of a typical Swedish clerical family.He had three sisters and a brother, Samuel,

who was to succeed their father as vicar ofStenbrohult in Smland. Samuel is known as

the author of a work on bee-keeping, a subjecttrue to the th century interest in useful sci-ence. A Church career was pre-ordained forCarl but required one or two years at university.

Linnaeus attended grammar school in nearbyVxj and, if legend is to be believed, was alack-lustre pupil; this again is a traditionemanating from Linnaeus himself and his notaltogether reliable autobiographies. His physicsteacher, a doctor called Johan Rothman, spot-ted his genius and supported his interest in theless utilitarian study of plant life. (In schoolsof the past there was nearly always a mentor ofRothmans kind, may their names be praised.)He told the worried parents that their first-born should abandon theology for medicine.

is is indeed what happened, but the paren-

tal anxiety was understandable. Medical postsin Sweden were extremely few in number,

whereas theologians had a guaranteed jobmarket. en again, they had heard rumoursabout the godlessness of medical science, for

after all, it was the physicians who, a genera-tion or so earlier, had imported the seditiousdoctrines of Descartes to the universities.

From Vxj Grammar School, Linnaeusventured forth to the relatively new LundUniversity in the province of Skne. Linnaeuscapacity for finding benefactors is attributablenot only to his rare ability but also to hischarm and boldness. is time it was theProfessor of Medicine, Kilian Stobaeus, whotook Linnaeus into his home, though the mis-tress of the house objected to the new residentreading in bed by candlelight, thereby threat-ening to send everything up in flames.

Lund suited Linnaeus purposes for only a year

or so. In he moved to Uppsala in the

OPPOSITE PAGE

Rshult in the prov ince of Smland,Linnaeus birthplace.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

13/48

11

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

14/48

12

province of Uppland, where there was a biggerand more ancient university, founded in .ere he found two Professors of Medicine,Olof Rudbeck the Younger and Lars Roberg,both of them on the point of retirement.

Linnaeus naturally took a sidelong glance attheir positions and was anxious to display hiscapabilities then and there. With a few inter-missions he spent seven years in Uppsala.e intermissions were occasioned by journeysto Lapland () and Dalarna (). Most ofhis studies were pursued unaided, but he alsogot a foot inside the door of Olof Rudbeck the

Younger. Linnaeus ministered to the Rudbeckfamily until, for uncertain reasons, MistressRudbeckia showed him the door. He alsoearned the confidence of Lars Roberg. Roberg

was an interesting man, a cynic in the philo-sophical sense and outstandingly erudite. Hehad a reputation for being rather oddbadlydressed and the owner of a great librarybutLinnaeus rightly admired him.

e early medical studies reflected by Linnaeusnotes from this period present a remarkableblend of traditional belief or superstition andmodern mechanistic medicine. One is certainlyintrigued to find Linnaeus, visiting his family

in Stenbrohult, saving his sister from the agueby wrapping her in the carcase of a newlyslaughtered sheep. In his lectures he tells hisstudents that, if you apply snaps to a puppy it

will remain small, and that the male progenyof a white woman and a black man acquiresa black penis. He is famous for his persistentbelief that swallows did not migrate southwardsbut hibernated at the bottom of lakes, as if theyhad gills and fins. (is popular belief has beenput down to the fact that swallows fly close tothe surface of the water in pursuit of insects,but one is entitled to demand better things ofan academic naturalist.) Mistakes like thismay seem embarrassing, but they are moreappropriately to be regarded as tensions ina culture of many different strata.

OPPOSITE PAGE

Copper engraving of Carl Linnaeus byAugust Ehrensvrd, 1740.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

15/48

13

At the same time, as hinted above, Linnaeuswas convinced of the truth of the new mech-anistic physiology, readily summarised in thethesis of Homo machina est, i.e. man isa machine. Lars Roberg, for example, could

put this in the following terms: e hearta pump, the lung a bellows, the stomach amixing bowl. Coupled with another ofLinnaeus favourite adages, Homo est ani-mal, this way of looking at humanity hada bold and modern ring. e fundamentalnotion was that of the simple plan of Nature,as confirmed by the new physics, and ulti-mately by Newton. In other words, on closer

inspection Creation proved to be based ona few sensible laws and not on a welter ofexceptions. Nature, thus viewed, was readilycomprehensible, which can sometimes excusethe conclusions which Linnaeus and others

jumped to, including breathtaking analogiesbetween the natural kingdoms and betweennature and culture.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

16/48

14

Linnaeus was above all attracted to natural his-tory, and especially botany. He was a divinelytalented botanist, but like any other great sci-entist or artist still had to work hard to achievehis position. During excursions of different

kinds in and around Uppsala and through histeaching in the University Botanical Gardens,originally laid out by Olof Rudbeck the Elderin the s, he gained knowledge, contactsand reputation. Olof Rudbeck the Younger,his employer and benefactor, showed him thefamous bird book he had painted in the s,based partly on material from a journey toLapland, Swedens first scientific expedition.

Also in Uppsala at that time was Petrus Artedi,another medical student and Linnaeus inter-locutor and rival in terms of scientific acumen.Together they hatched magnificent plans fora reformed science characterised by order andbreadth of perspective. At home in his studentsden, Linnaeus collected more and more naturalexhibits, books and manuscripts of his own

writing. A quotation:

Reader, you should have seen his museum,which was open to the listeners, and, full ofadmiration and delight, you would have lovedits host. e ceiling he had adorned with birdskins, one wall with a Lapp costume and other

curiosities, the other wall with large plants andcrustaceans, while both the others were linedwith books of natural science and medicine,and with docimastic* instruments and stonesneatly arranged. e corners of the room wereoccupied by high branches of trees which hehad taught birds of nearly thirty species toinhabit; on the inside of the windows, finally,there were large clay vessels filled with soil in

which rare plants found nourishment.

Linnaeus prepared for his professional dbut,but to qualify for a doctorate in medicine hehad to travel abroad. Since the second half ofthe th century, it had become customary forSwedes to travel to Holland for their doctoral

* Docimasy: the assaying of ores or metals.

OPPOSITE PAGE

Linnaeus study in the Linnaeus Museum,Uppsala. In Linnaeus day both the house andthe garden were an international centre

for scientific research and teaching.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

17/48

15

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

18/48

16

disputations. e country had thus becomean important influence on Swedish intellectuallife. (Artedi arrived there at the same time asLinnaeus but drowned one dark evening inan Amsterdam canal.) e Netherlands were

also a much more suitable place for publishingworks of scholarship. As an experience,a foreign stay of this kind was invaluable and,given the chance, would be extended in bothtime and space. Linnaeus was to spend threeyears on the continent of Europe, mostly inthe Netherlands, but with brief visits to Franceand England. Not that this really made hima cosmopolitanmodern languages, for exam-

ple, did not come easily to himbut the aca-demic contacts and friends thus acquired wereimmensely beneficial in the long run. It wasthrough them that he was to gain a worldwidereputation.

A few weeks later Linnaeus had taken his doc-torate at the little university of Harderwijk.

e subject of his thesis was ague caused by a

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

19/48

17

spannerclay, actuallyin the human works,a truly modern, mechanistic exposition,presented with the massive self-assurancethat typifies all Linnaeus medical writings.In addition, the little collection of botanical

rules entitled Fundamenta botanica ()was printed, together with greater and lesserworks like Bibliotheca botanica (), Generaplantarum () and Classes plantarum (),the illustrated workHortus Cliffortianus(),his friend Artedis posthumous Ichtyologia() and a few more besides. Linnaeus washis own science industry. He had been put incharge of the garden at Hartecamp, an estate

belonging to the wealthy banker GeorgClifford, and his duties there sometimesprevented him from seeing his own writingsthrough the press. Instead he enlisted the aidof his friends. He certainly didnt waste time!

It was in the Netherlands, then, that Linnaeusmade a name for himself and, after a couple of

detours to France and England, one feels he

might very well have settled in Europe for good,but in he returned home to Sweden, neveragain to venture into the great wide world.

Everything in order:the new natural science

IN AMSTERDAM HE WAS lucky enough to makefriends with a kindred spirit, the wealthy nat-ural historian Johannes Burman, who promisedto help him publish his Systema naturae(),the manuscript of which he had brought withhim from Sweden. If ever there was such athing as the Linnaean project, this was it.

Typographically, not least, the composition ofits great tables was a magnificent achievement.Perhaps the Systema naturaewas originallyintended to consist of a number of maps

which could be put up on the wall, illustratingthe three kingdoms of Nature, with everythingdisplayed, both the great units and the pro-gressively smaller individualities. Quite often,

in fact, he referred to his system as a kind of

IF EVER THERE WAS SUCH A THING ASTHE LINNAN PROJECT, THIS WAS IT

Title-page of the first edition of LinnaeusHortus Cliffortianus, Amsterdam 1737.

OPPOSITE PAGE

The botanical garden in Harderwijk. The gingkobiloba tree is the oldest in t he Netherlands and

may even have been planted by Linnaeus.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

20/48

18

military mapping: Nature, like society, consist-ed of kingdoms, provinces, districts and indi-

vidual smallholdings from which the soldierwas collected. Linnaeus having grown up dur-ing the great wars, the analogy came naturally.

Not that he was an adherent of the old politicalsystem which had now been toppled, but hewas almost obsessed with lucidity and order.On one occasion he appointed himself generalof Floras army, an apt title in spite of thatgoddesss peaceful attributes.

Linnaean science was founded on divisio etdenominatio, division and naming, which

meant breaking Nature down into a numberof larger or smaller boxes to be labelled andput in the right places. As the criteria of div-ision, Linnaeus used, for plants, their sexualcharacteristics, which had been discovered atthe end of the th century but were by nomeans universally accepted. One could go togreat lengths in interpreting Linnaeus fascina-

tion with the ubiquitous procreative games of

Nature, from which not even the innocentflowers were excluded. In addition to perhapsthe first explanation that springs to mind,that Linnaeus was a kind of Peeping Tomof natural history, one can also identify a reli-

gious motif, that of Nature, in obedience to itsCreators call, being fruitful and multiplying.is, to Linnaeus, is its prime task, and it is inthis way that life is sustained in all its diversity.His delight in the resemblance of plants to manalso harks back to ideas concerning the simpleplan of Nature. Further inspiration may havecome from alchemy, which excelled in a kindof scientific nuptial metaphor very similar to

Linnaeus. Plants also celebrate weddings,in a whole variety of configurations, eitheropenly as in the case of the phanerogamsor secretly as with the cryptogams.

e animals, in turn, are divided accordingto more varied criteria: the quadrupeds, oras Linnaeus would perceive and term them,

Mammalia, were divided, among other things,

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

21/48

19

according to the number and position of theirbreasts/udders. Minerals or stones, similarly,

were divided according to external characteris-tics and not with reference to any chemicalcomposition. Like plants and animals, they are

arranged in the Linnaean hierarchy beginningwith the largest and ending with the smallest,viz regnum, classis, ordo, genusand species. edifferent species were given long names tobegin with, but from (Species plantarum)and (Systema naturae, tenth edition, ani-mal section), they were given the dual names

which have since become standard practice innatural science. e white anemone is still

calledAnemone nemorosa and the domestic catFelis domestica, both with L. added to show

who named them.

ese are technicalities, of which Linnaeanscience has many. Not that this makes it dif-ficult; on the contrary, it can be reduced to arefined hobby. On the other hand, the device

has been infinitely effective as a means of get-

ting a mental hold of Nature and in this waygaining control of it. ere is more to a namethan meets the ear.

e late editions ofSystema naturaescan the

entire range of creation, from the stars downto the microorganisms. e extra-terrestrialworld, admittedly, commands only a mentionbut is nonetheless important as a framework.Linnaeus is more exhaustive on some pointsthan others. As usual the insects predominate

while only the rough outlines of the crypto-gams were known. us the path descendingfrom the stars through the whole of creation

is a jagged one. Often the diversity was over-whelming; sometimes the right transitionswere lacking. Linnaeus was really contendingwith a fundamental difficulty, because at oneand the same time he was looking for differ-ences and connections, both ladders andchains, as it were. e former fitted in better

with the emphasis of traditional religion on

mans supremacy, for example. e latter was

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

22/48

20

LARGE PICTURE

Aquilegia vulgaris

SMALL PICTURE

Paeonia festiva

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

23/48

21

LARGE PICTURE

Aesculus pavia

SMALL PICTURE

Lilium bulbiferum

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

24/48

22

more in keeping with the thinking of thetimes. A new epistemology and a successionof new discoveries in natural history demon-strated the impossibility either philosophicallyor scientifically, of keeping Nature within

bounds. John Lockes critique of essentialism(that is, the theory that species could be de-fined in terms of essence) and a number ofobserved borderline organismssuch as thefreshwater polyp, the corals and the primatescame as challenges to the old structure.

One of the patterns of thought most dear tothe th century was the concept of the great

chain of being. To Linnaeus this became moreand more important. Naturally he regardedCreation as a hierarchy with man at the top;his startling positioning of the human race inthe same order as the apes has endured, manbeing dubbed in Homo sapiensof theorder ofPrimates. But the chain had to hangtogether at the bottom, and Linnaeus searched,

through his reading and through colleagues,

for transitional human beings. He lent hisconfidence to dubious reports of a capturedmermaid, and he wrote longingly of the possi-bility of examining her. He also allowedhimself to be deceived by other travellers

tales, which seemed to confirm the existenceof sub-humans with tails or humans withthe arms of apes. ese are even admitted toSystema naturae, under names like Homotroglodytes(referring among other things toalbinos) and Homo lar(the gibbon). ese ele-ments bear witness to his aim of doing justiceto the diversity and coherence of Nature, twoproperties which not only agreed with what

scientific research seemed to be saying but alsowith the concept of an infinitely wise andgenerous Creator. ey are at one and thesame time unprejudicedpre-Darwinistand prejudiced.

e Linnaean project had begun. Cast in themould of the Linnaean books of rules, it also

had the purpose of listing and ordering the

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

25/48

23

whole of Creation. All that now remained wasto carry it out.

Professor in Uppsala

LINNUS, THEN, HAD LEFT the Netherlands.Traditional biographies usually put this downto his promise to his betrothed, Sara LisaMoraea. (us the autobiography: Travelledstraight to Falun to see his beloved, who fornearly four years had been waiting for her dearUlysses.) But it is also conceivable that heneeded to put his house in order in a more ma-terial sense. At all events, this love story was no

coincidence. Sara Lisas father was physician atthe Falun copper mine, which was one of thebest appointments open to a Swedish physicianand something worth banking on if the aca-demic plums fell in the wrong direction. Herbetrothed was a promising young medic,a future somebody. By all the laws of higherromance, Linnaeus ought to have returned

home earlier.

ere was in any case no endur-

ing romance about their ensuing marriage.Sara Lisa was a worthy woman and Linnaeus

was probably made to keep his distance. Butonce again, let us not romanticise yesterdaysloves nor expect great men to be uncalculating

and their wives to be self-sacrificing slave girls.

Linnaeus spent a couple of years in medicalpractice in Stockholm before, after a goodmany ins and outs, becoming Professor ofMedicine in Uppsala in . Once in positionhe displayed a rare degree of energy rivalledonly by that of Olof Rudbeck the Elder. Hisprofessorial duties involved teaching dietetics,

materia medica, and natural history. He wasin charge of the botanical gardens, the successof which must be weighed against the eco-nomic and climatological difficulties he hadto contend with. Nor must we forget that italso involved looking after a small menagerie.Linnaeus was several times Vice Chancellorof Uppsala University, which had something

like a thousand students. For many years he

AT ALL EVENTS, THIS LOVE STORYWAS NO COINCIDENCE

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

26/48

24

was Inspector to the Smland Student League(a sodality of students from that part ofSweden). In addition he was several timesPresident of the Royal Swedish Academy ofSciences, founded by himself and a number

of like-minded people in . He also be-came, in , Secretary to the UppsalaScientific Society. From time to time, and

with mixed feelings, he served as a kind ofcourt naturalist to the King and Queen inStockholm. In the summer he went on hisprovincial tours.

Above all, though, Linnaeus was responsible

for large groups of students and tutored nofewer than dissertations, nearly all of

which he wrote himself. Over the years animmense quantity of scientific writings camefrom his pen, to the quite considerable finan-cial benefit of his publisher. To this must beadded his prolific correspondence, only aminor portion of which has been published,running to about twenty volumes. e full

quantity was once estimated at upwards of, letters, but the true figure is muchhigher.

is efficiency is hard to account for, but let us

once more indulge in a climatological specula-tion. A colleague during the Romantic period,geobotanist Gran Wahlenberg, declared in that Linnaeus, then, in common withhis science, is an excellent child of the naturalhistory of his native countrythe brief, in-tense summer when the long daylight allowslate nights of study, the cold winter whichhones the intellect. Above all Wahlenberg

points to the combination of forest and plainresulting from the intrusion of the UpplandRidge into the landscape. To this is added theimpact of the air on the slopes, stimulatingand capable of activating the senses. Or rather,sensual lifea necessary attribute of thenaturalist-researcher. Such are the surround-ings suitable for universities and successfulscientists.

OPPOSITE PAGE

Alexander Roslins portrait of Linnaeusfrom 1775.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

27/48

25

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

28/48

26

Compass, magnifying glass and pocket bookwith Linnaeus notes from the Lapland journeyof 1732.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

29/48

27

Linnaeus the traveller

IN SWEDEN, LINNUS IS KNOWN above all for histravel books. Topographical writings are popu-lar everywhere because they have so much totell us about past ages. Another of the attrac-tions of the Linnaean journeys is that they are

written in Swedish, and a very bracing Swedishat that. ey are not so uncontrived as Linnaeusimplies when, with false modesty, he disclaimsmembership of the nightingales of Pliny, butthey are less stilted than other contemporary

writings and outstandingly concrete. Linnaeuscuriosity and immense knowledge of his sub-

ject are an unfailing guarantee of the mot juste.

He was capable of clothing his impressions ina concise, often antithetical and reiterative style la Baroque, with dashes of classical mytholo-gy, hastily jotted down as he went. Even todaythey are a favoured travelling companion ofthe Swedish reading public.

It is tempting to see in them the foundations ofa specific Swedish feeling for nature. ey were

already viewed in this light, for example, bythe statistician Gustav Sundbrg when, in ,he published an influential collection of aphor-isms about the Swedish national character.Swedes, unlike Danes, are uninterested inpeople but very interested in nature, and thislove of nature was greatly inspired by Linnaeus.Invariably, he mistakenly continues, the focusof attention is on summer. For Linnaeus, bothsummer and winter in the Nordic countrieshave their peculiar merits, though winterscome often in disguise. In all fairness, theSwedish feeling for nature is certainly rootedin Linnaeus, but it did not begin growing in

earnest until the turn of the last century, asthe old agrarian society became urbanised andindustrialised. But be this as it may, Linnaeus

journeyings are Swedish classics, and it is a pitythat their delights should largely be accessibleonly to Swedish readers.

e first of these provincial journeys, toLapland, was financed by the Uppsala

IN SWEDEN, LINNUS IS KNOWNABOVE ALL FOR HIS TRAVEL BOOKS

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

30/48

28

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

31/48

29

Scientific Society at the instance of OlofRudbeck the Younger. Linnaeus was then a

vigorous -year-old. It was a journey full ofprivations. Later on, it is true, he was to exag-gerate its length and the perils it entailed, buthis narrative (which remained unpublished un-til ) inspires admiration enough. Linnaeustravelled on his own along the east coast ofSweden up to Lule, where he turned in to-

wards the mountains, crossing them on footand continuing as far as the Arctic coast on theNorwegian side. Returning the same way, hecontinued, with various minor detours, roundthe Gulf of Bothnia and down the coast of

Finland, crossing back to Sweden and Uppsalaby way of the island of land. In five monthshe had covered over , km. e scientificharvest was a rich one. e Flora Laponica() was a trump card in his Dutch publish-ing. An unknown corner of Europe had nowbeen described and published. ere was alsothe harvest of personal experience. e timespent in the mountains and together with the

Sami (Lapp) people had convinced him of thesuperiority of the simple life over urban com-forts. When it suited him, Linnaeus readilypreached a kind of medical primitivism andgreenwave gospel.

e purpose of the Lapland journey in wasprimarily scientific (although the list of topicsfor investigation included some fairly oddproblems, such as the question as to whetherNoahs Ark had come to rest on the reskutanmountain peak in the province of Jmtland).Linnaeus travelled on his own and took consid-erable risks. His journey to Dalarna, in ,

was commissioned by the Governor of thatprovince in Falun and had the economicpurpose of identifying common assets in thecountry at large as well as unknown natural re-sources and, for example, collecting intelligenceabout Norwegian mining activities at Rros.is time Linnaeus headed a small group ofstudents who assisted him and at the same timereceived instruction from their young leader.

OPPOSITE PAGE

Title-page and may tree from rtaboken,Linnaeus earliest known manuscript from 1725.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

32/48

30

e pattern resembles that of the journeysundertaken by Linnaeus as an Uppsala profes-sor in the s. e first of those journeys,to the islands of land and Gotland in ,preceded his inauguration; the subject of hisinaugural lecture was the necessity of explor-ing ones own country. ese expeditions

were paid for by the Estates (i.e. Parliament),in the hope of a payback through the reformof economic policy. Linnaeus journeys, accord-ingly, were to be published, and publishedin Swedishthe sole exception to this rulebeing the recurrent Latin descriptions of spe-cies. It is very doubtful, though, whether the

Swedish peasantry paid all that much attentionto Linnaeus writings, which were not to be-come best-sellers until much later.

We find ourselves travelling in the companyof an all-seeing eye, a horseman continuallydismounting to scrutinise the flowers at theroadside, making notes and gathering material.e utilitarian aspect is very much in evidence,

OPPOSITE PAGE

Hortus Cliffortianus, both the book and anallegory by Jacob de Wit.

Linnaeus painted in his Lappish costume byMartin Hoff man, 1737. When he went to theNetherlands in 1735 he took the costume,his herbarium and the manuscript ofFloraLapponica with him.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

33/48

31

for example, in the Vstergtland Journey(), which took Linnaeus to the smallmodel society of Alingss with its industries,

which were cherished by the Hat* rgime andviewed with approbation by Linnaeus, and toGteborg (Gothenburg), where he felt thespindrift of Holland. Much is made ofLinnaeus feeling for some kind of pristinenatural environment, but he was also favoura-bly disposed to towns, so long as they con-formed to his image of a modern community.e town, admittedly, could mean vanity andidleness, but it could also echo with the ham-mer blows of honest toil.

e journeys, then, reflect not only Linnaeuslove of nature but also his patriotism. And it

was above all the cultivated landscape whichcommanded his attention. On the last of hisprovincial journeys, to Skne in , he

* e prominent, pro-reform political party between the sand s.e Caps were their principal adversaries.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

34/48

32

UPPER LEFT

Echinops ritro

UPPER RIGHT

Tropaeolum majus

LOWER LEFT

Sempervivum tectorum

LOWER RIGHT

Papaver orientale

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

35/48

33

travels in style, by coach, and in the midst ofpouring rain and bad temper he delights inthe fertility of the soil. As he grew older, it wasman-made Skne rather than the thin, stonysoil of his native Smland which became hisideal province and landscape. He was no trueRousseauan.

The Linnaean project

THE LINNAN PROJECT WAS a combination ofthemes religious and secular. It was mans dutyto wonder at Creation in all its diversity and indoing so to give thanks to the Creator for Hisgenerosity. Linnaeus never tires of praising the

deity, but as a Creator, not as a Saviour. erewas a certain element of tactics involved here:natural science, natural history, could benefitfrom the backing of religion, but this gratitudealso contained the seeds of a worldly interestin nature, concerned with things beneficial toman. e utilitarian aspect is one of the fore-most characteristics ofth century Swedenand Linnaeus was one of its leading lights.

Everywhere he saw a purpose in Nature, eachindividual thing had its purpose and useful-ness, and most things, in the ultimate analysis,existed for mans benefit. On the other hand,Linnaeus did not lapse into a trite enumera-tion of all the benefits derived by man fromdivine benevolence. His optimism is counter-balanced by lamentations over mans wretch-edness and by a profound insight into the

workings of Nature.

To this very subject of the workings or inter-action of Nature he was to devote a number ofdissertations, such as Oeconomia naturae()

and Politia naturae(). Nature has threeconsecutive stages:propagatio, conservatio anddestructio. ese are so ingeniously connectedthat, in the blunt words of the Swedish prov-erb, one mans death is the other mans breath.In destructio, for example, Natures police, thepredators, dominate the scene. ey too areneeded, and they keep Creation clean andbeautiful. is version of the old theodicy

EVERYWHERE HE SAWA PURPOSE IN NATURE

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

36/48

34

Linnaeus home and place of work for 35 yearsin Uppsala now houses the Linnaeus Museum.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

37/48

35

problemthat of reconciling a good andomnipotent deity with the presence of imper-fections and evil in Creationis not original,but Linnaeus solution, instead of beingRococo and superficial, is sincerely felt andredolent of blood and pain. It also incorpor-ates man, who like everything else is includedin the cycle of Nature. e following excerptcomes from the Vstergtland Journey, asLinnaeus, in a churchyard, muses lightheart-edly on a serious subject:

When I dig the soil of churchyards, I takethe parts which have constituted and been

transformed by human beings into humanbeings; if I take them to my kitchen gardenand put plants in them, from this I get cab-bage heads instead of human heads, but ifI boil these /cabbage/heads and give them topeople, they are transformed once again intopeoples heads or to other parts etc. us wecome to eat up our dead, and in so doing

we prosper.

One can of course attempt to attributeLinnaeus infatuation with order to some innerunease. at certainly existed and there wouldindeed be justification for pursuing a morepsychological line of interpretation. (If so,of course, one must guard against tarringpresent-day taxonomists with the same neu-rotic brush.) But there is also a big-Swedishmegalomania, rooted in the Rudbecks, fatherand son, who also entertained grandiose butimpossible plans for covering the whole ofNature, all ages, full scale and in great detail,conclusively. It all sounds like a Gothic dream,a patriotic thought that everything great and

remarkable should emanate from the ancientScandinavians, but the remarkable thing ishow very nearly it came true. Above all weshould note the fruitful inspiration of modernscience, which was well on its way toward inte-grating every corner of Europe. Linnaeus wasa disciple of Bacon and wanted to be a Newtonof the life sciencesNewton whom, otherwise,he barely comprehended.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

38/48

36

e Linnaean project was outstandingly suc-cessful. Innumerable people were induced, andstill are, to take part in it. All over the world,research is working on it. But in one sense it

was a fiasco, namely because it cannot bebrought to a conclusion. Linnaeus, dubbed thesecond Adam by one of his colleagues, clearlybelieved that fairly soon, and at all events dur-ing his lifetime, he would have created for him-self a comprehensive view of Creation. His dili-gence was enormous and a growing network ofcontacts left him no rest. And so the variouseditions of his Systema naturaegrew in numberand bulk, from the folio pages of the first

() to the , pages of the twelfth (), including something like , mineral,plant and animal species. Classifying and nam-ing such an immense number was a remarkableachievement, but of course it was only the be-ginning of what can never be finished. Alreadyby the end of the th century, the number ofspecies on Earth was estimated at one million,

while nowadays there is talk of some to

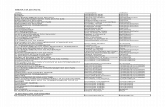

Carl Gustaf Ekebergs zoological wall chartswith notes, ca. 1749. The Latin namesare believed to have been added byLinnaeus himself.

LINNUS CHARISMA WAS ESPECIALLY BESTOWED UPON

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

39/48

37

million, perhaps more, untold numbers ofwhich will never come to be described.

Linnaeus must, sometime or other, havedoubted the possibility of completing his task,or at least of doing so personally. Confrontedby the bottomless wealth of Nature, he musthave felt not only enthusiasm but alsoexhaustion.

The Apostles

LINNUS WAS A MODERN PROFESSOR, a projectcreator and organiser with excellent contactsin the community at large. He was capable of

inspiring his pupils to great deeds, and heknew the right strings to pull when money wasneeded. Benefactors included the King andQueen (Adolf Fredrik and Lovisa Ulrika) andthe Swedish East India Company. Linnaeuscharisma was especially bestowed upon aninner circle, known as the Apostles, who weresent forth on voyages of exploration. Many ofthem actually suffered martyrdom in the field,

sacrificing their lives for science and its master.ey travelled in all directions: one large group

voyaged eastward, in the direction of the EastIndies and China. On their way they stoppedoffin Spain and at the Cape, often for consider-able periods, and these places were an impor-tant research field for some of them, including

Anders Sparrman and Carl Peter unberg.Once in China, their movements were severelyconstricted. Pehr Osbeck, for example, washounded back to his ship from innocent botan-ical excursions by Chinese boys throwing stones.Similar conditions prevailed in Japan, whichunberg visited with the Dutch East India

Company. rough patience and cunning,unberg overcame the difficulties, therebybecoming the pioneer of modern research intothe Japanese flora. To cover the interior of Asia,Linnaeus was planning to dispatch Pehr Kalmto China overland through Russia, but nothingcame of this. Instead it was Johan Peter Falck

who travelled eastward. His findings provedamong other things to be of ethnographic

LINNUS CHARISMA WAS ESPECIALLY BESTOWED UPONAN INNER CIRCLE, KNOWN AS THE APOSTLES

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

40/48

38

Lfling Berlin

Hasselquist

Forsskl

Falck

Trnstrm

Adler

a, b, c

a

b

c

EUROPE

ASIA

AFRICA

NORTHAMERICA

SOUTHAMERICA

NORTHAMERICA

SOUTHAMERICA

AUSTRALIA

ANTARCTICA

A R C T I C O C E A N

A T L A N T I C O C E A N

A T L A N T I C O C E A N

P A C I F I C O C E A N

I N D I A N O C E A N

S O U T H E R N O C E A N

CaspianSea

Black

Sea

Iceland

Spitsbergen

South Georgia

Cape Horn

Riiser LarsenPeninsula

Cape ofGood Hope

Kerguelen

Madagascar

Arabia

Ceylon

India

Greenland

Sumatra

JavaTimor

Borneo

Formosa

NewGuinea

Japan

Hawaii

NewZealand

New

Cale-donia

NewHebrides

Fiji

Tonga

Tahiti

Marquesas Islands

EasterIsland

Arctic Circle

Tropic of Cancer

Equator

Tropic of Capricorn

Antarctic Circle

AdlerAfzelius

BerlinFalckForssklHasselquistKalmLflingMartin

OsbeckRolander

RothmanSolanderSparrmanThunbergTornTrnstrm

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

41/48

39

interest. e unfortunate Falck took his ownlife in Kazan, while the benign, ever useful Kalm

went on the long voyage to North America, call-ing on Benjamin Franklin and visiting Niagara,of which he penned the first scientific description.

Anton Martin travelled to the Arctic Ocean, suf-fered frostbite in his legs and spent the rest of hisdays in a miserable condition. Daniel Rolandertravelled to South America, returning in a stateof mental confusion. Linnaeus favourite pupil,Pehr Lfling, died in Venezuela after successfulbotanical researches there. Fredrik Hasselquist,supported both by Linnaeus and by the Uppsala

faculty of theology, went to the Holy Land butdied in Smyrna, after which his collections werepurchased by the Queen of Sweden, LovisaUlrika. Peter Forsskl, one of the really interest-ing disciples and of dissident political persua-sions, joined a Danish expedition to Arabia,

where he and the other members, except fortheir leader, Carsten Niebuhr, died of malaria.

e results of these enormous efforts mayseem relatively limited. e travellers senthome descriptions of plants and animals,

wrote in wonderment about the life of strangepeoples and the magnificence of the naturalscene. e travel descriptions, several of them

published by Linnaeus, evidently sold well,even though they consist mainly of descrip-tions of species for the initiated. Often theexplorers did little more than scratch at thesurface of things. But perhaps the main signif-icance of their journeys was symbolic, as a sci-entific adventure and form of sacrifice. ey

were also of importance for the future, in the

sense of scientists thus having assured them-selves of a place on the great voyages by landand sea. Linnaeus pupils Anders Sparrmanand Daniel Solander circumnavigated theglobe with James Cook, and when, just overhalf a century later, HMS Beagle set out on its

voyage round the world, there was a place onboard for the young Charles Darwin.

OPPOSITE PAGE

Linnaeus sent his apostles around the worldon perilous voyages of discovery. Many of themdid pioneering scientific fieldwork; some ofthem failed to return.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

42/48

40

Linnaeus left his personal imprint on a greatdeal ofth century science, not only inSweden but in the whole of the western world.His concentration on collecting and classify-ing may sometimes appear quirky, but clearlyit fills an important gap. Natural history had

closed the lead which physics had gained inthe scientific revolution of the th century,and it did so very much by continuing witha kind of Baroque rationalism and system-building. Lesprit de systme, the urge to trapreality in a comprehensive net, is typical ofthis Linnaean th century. To this end, in-creasingly specialised manuals and journals

came into being, as well as popular presenta-tions, e.g. for women. Rousseau, that sorrow-ful amateur botanist, for example, wrote hisLettres sur la botaniqueaccording to Linnaeanmethod.

e passion for system extended beyond thethree realms of natural history, to which acolleague of Linnaeus wished to add a fourth,

namely the aquatic kingdom. Linnaeushimself went to a great deal of trouble toclassify diseases in his nosology* (Generamorborum, ); Jeremy Bentham accordedmuch the same treatment to the virtues, whileother writers classified books or economy in

Linnaean fashion. e classification of humanraces, an activity which in time was frequentlyto produce questionable results, also begins

with Systema naturae. In all this, and inother things besides, one can speak of aLinnaeanism of the time, the boundariesof which had yet to be defined by historicalresearch.

Linnaeus, then, achieved remarkable success.During his lifetime he was elected to member-ship of most existing academies. After hisdeath the Linnean Society of London wasfounded, based on his collections, which hadbeen sold to England by his widow, Sara Lisa.

* e classification of diseases.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

43/48

41

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

44/48

42

Soon afterwards came the foundation ofthe Socit Linnenne in Paris, which was toflourish soon after the Revolution of.For various reasons beyond the scope of thisessay, Linnaeus was internationally viable. He

was needed, not least by virtue of the language

reform he had introduced. Linnaeus created akind of Linnaean which is not spoken but isstill being written. With his Systema naturaehe gave research an overriding task, a project.

And in Sweden, as we have already seen, hecreated a special way of travelling and of ex-periencing nature.

Was Linnaeus a satisfied man? What joy did hehave of his success? Laudatur et algethe is

renowned but feels coldwas Linnaeus motto.And so, for his own use and for the edificationof his rather unruly son, the ageing Linnaeuscollected examples of the darkness of humanlife, a theologia experimentalis, which hecalled Nemesis divina, over all the injustices

committed by other people, adversaries andthose who envied him, against their ownkinsmen, against God and against Nature.Natures interpreter was not the happiest ofmen. His miraculous memory was obliteratedby a stroke, after which he admired his own

writings but could not understand that hehimself was the author of them. His only son,

Carl, succeeded him but lived for only a fewmore years after his fathers death in .

The sexual system and the binary nomenclature

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

45/48

43

Linnaeus first published his sexual system in in the Systema naturae, laterapplying it to every then known species in the Species plantarum (first edition), which was based to a great extent on material from his garden. e sexualsystem is not now accepted as a classification corresponding to the actual rela-

tionships between plants, and it has therefore been abandoned, but at the timeit represented a method of definition and classification far surpassing anythingpreviously known. Linnaeus was aware of the theoretical weaknesses and artifi-cial character of the sexual system, but quite justifiably he remained convincedof its practical usefulness until the end of his life.

e sexual system first divides the plant kingdom into classesaccording tothe number of stamens (I Monandria, II Diandria, etc) or, from No. XII on-wards, according to the arrangement of the stamens or sex distribution between

the flowers. Class XXIV represents the cryptogamia, with concealed sexualorgans. It is exemplified in the garden by the ferns. e number of the class iswritten in Roman numerals.

e classes are divided into ordersaccording to the number of styles or pistils inthe flowers. e designations of the orders are similar from class to class.Monogynia (with style), Digynia (with styles or pistils), etc., to Polygynia(with a great number of styles or pistils). e number of the order is written inArabic numerals.

e orders are divided intogenera, many of which agree with those we recognisetoday(Linnaea, Betula), although others have been subdivided or recombinedsince Linnaeus day. us Linnaeus genus designations are not always the sameas those we use now.

e genera are divided into species, which have double names (the system ofbinary nomenclature which Linnaeus introduced) e.g. Linnaea borealis, Betulanana. Linnaeus species classifications have by and large survived, although forvarious reasons many of their names have had to be changed.

Georg Dionys Ehrets original illustration of Linnaeus sexual system from 1736.

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

46/48

Chronology in brief

Born at Rshult, Smland Studies in Lund Studies in Uppsala Travels to Lapland Travels in Dalarna Travels to Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, England and France

Takes his doctorate of medicine at Harderwijk, NetherlandsFirst edition ofSystema naturae

Fundamenta botanica

Flora Laponica Medical practice in StockholmFounder member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and its first PresidentMarries Sara Lisa Moraea

Professor of Medicine, Uppsalaland and Gotland Journeys

Secretary of the Uppsala Scientific Society Flora Suecica Vstergtland Journey Fauna Suecica

Skne Journey Philosophia botanica Species plantarum Ennobled Buys Hammarby, near Uppsala

Tenth edition ofSystema naturae Linnaeus last edition ofSystema naturae Dies in Uppsala Death of Carl Linnaeus the Younger Linnaean collections sold in England

Picture credits

Cover photo and page 8 photo Teddy Thrnlund, UppsalaUniversity art collection

pages 2, 20, 21 and 32 Edvard Koinbergpages 4 and 6 Johnrpage 7 Riddarhusetpage 11 photo: Carina Glanshagen lmhults kommunpages 13 and 36 Centre for the history of science, Royal Swedish

Academy of Sciencespage 15 Olle Norling, Upplandsmuseetpage 16 Milieucentrum de Hortus, Harderwijkpage 17 bo Academys picture collectionpages 18 and 19 Tiofotopage 25 Nationalmuseumpages 26 and 30 Sren Hallgren and the Linnaeus Museumpage 28 photo: Lund University Library, Vxj City Librarypage 31 Teddy Thrnlund and t he Linnaeus Museumpage 34 Anders Damberg and t he Linnaeus Museumpage 38 Stig Sderlindpage 41 Helena Bergengren, TioFoto

page 43 photo: Uppsala University Library

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

47/48

-

8/2/2019 Linne_eng

48/48

CARL LINNUS (17071778) is Swedens most famous natural scientist.He set out to list and order the whole of Creation. His importance, however,is not confined to the international history of science. In a way he is also

a part of Swedish everyday life today, as the author of living classics which

people still read. The Swedes, perhaps, look on him primarily as a traveller

and explorer of their own country, while to others he is the father of the

modern classification of flora and fauna. But he was much more than this.

For example, he was an inspiring teacher who sent his students off onextraordinary voyages of scientific discovery all around the world.

2007 is the 300th anniversary of the birth of this great scientist whose

legacy lives on into our own age.