IndianJMedSci6611-3703196_101711

Transcript of IndianJMedSci6611-3703196_101711

-

7/24/2019 IndianJMedSci6611-3703196_101711

1/12

1

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 66, No. 1 and 2, January and February 2012

STRESS AND ITS RISK FACTORS IN MEDICAL STUDENTS: AN

OBSERVATIONAL STUDY FROM A MEDICAL COLLEGE IN INDIA

MADHUMITA NANDI, AVIJIT HAZRA1, SUMANTRA SARKAR, RAKESH MONDAL2,MALAY KUMAR GHOSAL3

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: Stress in medical students is well established. It may affect academic

performance and lead to anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and burnouts. There

is limited data on stress in Indian medical students. We conducted an analytical

observational study to assess the magnitude of stress and identify possible stressors

in medical students of a teaching hospital in Kolkata.MATERIALS AND METHODS:This

questionnaire-based study was conducted in the Institute of Post Graduate MedicalEducation and Research, Kolkata with consenting undergraduate students of 3 rd,

6th, and 9th (final) semesters, during lecture classes in individual semesters on a

particular day. The students were not informed about the session beforehand and were

assured of confidentiality. The first part of the questionnaire captured personal and

interpersonal details which could be sources of stress. The rest comprised three rating

scales the 28-item General Health Questionnaire to identify the existence of stress,

the WarwickEdinburgh mental well-being scale to assess the mental well-being, and

the revised version of the Lubben social network scale to assess the social networking.

The responses and scores were compared between the three semesters as well asbetween various subgroups based on baseline characteristics. RESULTS: Data from

215 respondents were analyzed approximately 75% were male, 45% came from

rural background, 25% from low-income families, and 60% from vernacular medium.

Totally, 113 (52.56%; 95% confidence interval: 43.35-61.76%) students were found to

be stressed, without significant difference in stress incidence between the semesters.

About 60% of the female students were stressed in contrast to 50% of the males, but

this observed difference was not statistically significant. The mental well-being and

social networking of stressed respondents suffered in comparison to their non-stressed

counterparts. CONCLUSIONS:The stress incidence in medical students in this institution

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Departments of Pediatrics, and 1Pharmacology, Instituteof Postgraduate Medical Education and Research,Kolkata, 2Department of Pediatrics, North Bengal MedicalCollege, Darjeeling, 3 Department of Psychiatry, MedicalCollege, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

Address for correspondence:Dr. Madhumita Nandi,6/6, Naren Sarkar Road, Barisha,Kolkata - 700 008, India.

E-mail: [email protected]

Access this article online

Quick Response Code: Website:

www.indianjmedsci.org

DOI:

10.4103/0019-5359.110850

PMID:

*****************************

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjmedsci.org on Saturday, January 02, 2016, IP: 125.161.213.32]

-

7/24/2019 IndianJMedSci6611-3703196_101711

2/12

2 INDIAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 66, No. 1 and 2, January and February 2012

INTRODUCTION

Stress in medical students is an established

phenomenon encountered worldwide and such

students seem to be under duress at all stages

of their academic career, including pre-clinical,

paraclinical, and clinical years.[1-4]Their overall

psychological distress is consistently higher

than in the general population and may impact

on their academic performance.[5,6]Stress may

foster anxiety, substance abuse, burnouts

leading to abandonment of studies, depression,

and even suicidal ideation.[3,7,8]

There are many possible stressors to which

medical students may be exposed. [9,10] The

pressure of a rigorous academic curriculumcoupled with frequent examination schedule

is an obvious factor. Various other perceived

sources of stress include personal factors

such as staying away from family, adjustment

to unfavorable hostel conditions, parental

expectations, etc., The medical education

system in India and the infrastructure in

medical colleges are generally not conducive

to amelioration of distress or facilitation of

coping. In fact, despite occasional reports,[11-14]

there are limited data regarding the magnitude

of the problem itself from the whole of the

country in general and eastern India in

particular. In view of the rapid pace at which

new medical institutions are coming up in India,

it is important to generate data regarding the

magnitude of student distress and its impact

on academic performance, dropout rates, and

professional development.

With this background, this study was conceived

as an analytical observational study to assess

the level of stress in medical students in a

teaching hospital in India, during various stages

of their MBBS course, and to identify factors

potentially responsible for inducing stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The population for this study comprised all

undergraduate (MBBS) medical students of

3rd, 6th, and 9th (nal) semesters of the Institute

of Post Graduate Medical Education and

Research, Kolkata. All students present in theirrespective class on the day of the study were

included. The participants were informed about

the nature and purpose of the study and were

assured of condentiality. It was explained that

responding to the questionnaire was voluntary

and there would be no monetary or other direct

benets from participation. Written informed

consent was obtained from each participant.

Those who refused were to be excluded. The

study protocol received clearance from the

Institutional Ethics Committee.

Permission was taken beforehand from

the teacher concerned on the day of the

study and the last 25 min of a 1-h lecture

class was utilized for conducting the survey.

The students were not informed about the

in India is high and is negatively affecting their mental well-being. Further multicentric

and longitudinal studies are needed to explore the incidence, causes, and consequences

of stress in our setting.

Key words:28-item general health questionnaire, medical students, revised Lubben social

network scale, stress, student distress, WarwickEdinburgh mental well-being scale

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjmedsci.org on Saturday, January 02, 2016, IP: 125.161.213.32]

-

7/24/2019 IndianJMedSci6611-3703196_101711

3/12

3STRESS IN MEDICAL STUDENTS

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 66, No. 1 and 2, January and February 2012

session beforehand. Those agreeing to

participate were asked to ll up a pretested

anonymous questionnaire to capture personal

data (excluding name and age), academic

performance, and stress inducing physical,

emotional, and social factors. These included

information on gender, percentage score in

last university examination, average monthly

family income, rural or urban background,

medium of study in school, whether staying

in hostel, and the number of siblings. The

rest of the questionnaire comprised three

checklists the 28-item General Health

Questionnaire (GHQ-28), WarwickEdinburgh

mental well-being scale (WEMWBS), andrevised version of the Lubben social network

scale (LSNS-R).

The GHQ-28[15,16]was used to assess current

mental health. This questionnaire was originally

developed by Goldberg et al. in 1979,[15] as

a 60-point screening questionnaire. Since

then it has been extensively used in different

sociocultural settings and in different abridged

forms. The GHQ-28 was designed from the

results of principal components analysis

based on the original GHQ. Its advantage

is that it assesses changes in individuals

daily functioning related to distress and not

personality characteristics. The GHQ-28

has four subscales: Depression, anxiety,

somatic symptoms, and social withdrawal.Each subscale contains seven items. The

respondent has to answer whether he or

she has experienced a particular symptom

or behavior recently. Each item is rated on a

four-point scale typically designated as not

at all, no more than usual, rather more than

usual, or much more than usual and the

bi-modal (0-0-1-1) scoring method is commonly

used to estimate the occurrence of stress

related to the item. Total score can range from

0 to 28. Total scores that exceed 4 out of 28

suggest caseness or distress. GHQ-28 is the

most well-known and popular version of the

GHQ. Adaptations of GHQ-28 have been used

in various countries and in various settings.[17-19]

The WEMWBS is a measure of mental

well-being focusing entirely on positive aspects

of mental health.[20,21] The scale consists of

14 items covering both hedonic and eudemonic

aspects of mental health including positive

affect (feelings of optimism, cheerfulness,

and relaxation), satisfying interpersonalrelationships and positive functioning (energy,

clear thinking, self-acceptance, personal

development, competence, and autonomy).

Respondents are required to select the

response that best describes their experience

of each statement over the past 2 weeks on a

5-point Likert scale none of the time, rarely,

some of the time, often, and all of the time.

All items are scored positively and the score

on each item ranges from 1 to 5. The overall

score is calculated as sum of the scores for

individual items, with equal weights, implying a

minimum possible score of 14 and maximum of

70. A higher WEMWBS score thus indicates a

higher level of mental well-being.

The LSNS-R was used to gauge perceivedsocial support received from family and friends.

It was originally developed in 1988 and was

revised in 2002.[22,23] The total score on this

scale comprises an equally weighted sum

of scores on 12 items used to assess size,

closeness, and frequency of contacts in a

respondents social network. All items measure

the level of perceived support received from

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjmedsci.org on Saturday, January 02, 2016, IP: 125.161.213.32]

-

7/24/2019 IndianJMedSci6611-3703196_101711

4/12

4 INDIAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 66, No. 1 and 2, January and February 2012

either family or friends, and the scores on

each item range from 0 to 5, with 0 indicating

minimal social integration and 5 indicating

substantial social integration. The total score

can therefore range from 0 to 60, with higher

scores indicating a greater level of social

support and lower risk for isolation. A score

less than 20 may indicate that the person has

extremely limited social networking and is at

high isolation risk.

Statistical analysis

The data were rst transcribed to an MSExcel

spreadsheet and then analyzed by Statistica

version 6 [Tulsa, Oklahoma: StatSoft Inc.,2001] and MedCalc version 11.6 [Mariakerke,

Belgium: MedCalc Software, 2011] statistical

software. Scores were not normally distributed

and have therefore been summarized by

median and interquartile range, in addition to

mean and standard deviation. Key proportions

have been expressed with 95% confidence

interval (95% CI). Subgroup comparisons

have been done between the three semesters

and by baseline characteristics. Scores

have been compared between subgroups by

MannWhitney U test (for 2-group comparison)

or KruskalWallis analysis of variance followed

by Dunns test for post hoc comparison (for

more than 2-group comparison). Categorical

data have been compared between subgroups

by Fishers exact test, with FreemanHaltonextension where necessary. All analyses

have been two-tailed andP< 0.05 has been

considered statistically signicant.

RESULTS

The institute has approximately 100 students

per year. None of the students present in class

on the day of the study refused participation,

but the response sheets of only those who had

lled up all four sections of the questionnaire

were analyzed. The responses of 74 students

in 3rd semester, 40 students in 6thsemester,

and 101 students in the 9 th semester were

analyzed (Total n= 215).

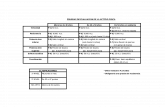

Table 1 shows the general characteristics

of the study population. It is noteworthy that

approximately 75% of the respondents were

male, 45% were coming from rural background,

25% from low-income (

-

7/24/2019 IndianJMedSci6611-3703196_101711

5/12

5STRESS IN MEDICAL STUDENTS

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 66, No. 1 and 2, January and February 2012

and 60% were unsatised with the available

social and recreational opportunities.

The frequency of these stressors was

equally applicable to all the three semesters

studied with few exceptions. Peer rivalry

appeared to peak during the nal semester

of study, while tension from political conicts

appeared to affect the 6thsemester students

most. There was no gender difference with

respect to the impact of these stressors, with

one exception. Of the 160 male students,

45 (28.13%) came from low-income families

in contrast to 8 (14.55%) of the 55 female

students (P = 0.047). Correspondingly,

52 (32.50%) of the male students felt

that financial constraints were negatively

influencing their academic performance,

in contrast to 9 (16.36%) of the female

students (P= 0.024).

There were no signif icant di f ferences

with respect to the occurrence of these

stress- inducing factors and basel ine

characteristics in the study participants, namely

with respect to ruralurban background,

stay in hostel versus home, English versus

vernacular medium background, and

presence or absence of siblings. However,

students from a rural background were more

Table 1: General characteristics of study cohort

Characteristic Overall(n=215) (%)

Semester 3(n=74) (%)

Semester 6(n=40) (%)

Semester 9(n=101) (%)

P value

Male gender 160 (74.42) 52 (70.27) 26 (65.00) 82 (81.19) 0.082

Rural background 95 (44.18) 28 (37.84) 14 (35.00) 53 (52.48) 0.071

Staying in hostel 152 (70.69) 54 (72.97) 24 (60.00) 74 (73.27) 0.270

Studied earlier in vernacular medium 129 (60.00) 42 (56.76) 20 (50.00) 67 (66.34) 0.156

From low-income families 53 (24.65) 14 (18.92) 10 (25.00) 29 (28.71) 0.342

No siblings at home 66 (52.80) 30 (40.54) 9 (22.50) 27 (26.73) 0.071

ThePvaluein the last column is from comparison between the three semesters by Fishers exact test (with Freeman-Haltonextension)

Table 2: Perceived frequency of individual stressors

Specifc question Overall(n=215) (%)

Semester 3(n=74) (%)

Semester 6(n=40) (%)

Semester 9(n=101) (%)

P value

Do you feel your socioeconomic status is coming inthe way of better performance in studies?

61 (28.37) 18 (24.32) 10 (25.00) 33 (32.67) 0.463

Are you satised with hostel/canteen facilities? 26 (12.09) 9 (12.16) 2 (5.00) 15 (14.85) 0.269

Are you satised with the library facilities? 49 (22.79) 20 (27.03) 6 (15.00) 23 (22.77) 0.347Are you satised with the examination system? 66 (30.70) 30 (40.54) 10 (25.00) 26 (25.74) 0.082

Do you feel there is excessive parental pressure toperform better?

31 (14.41) 10 (13.51) 7 (17.50) 14 (13.86) 0.816

Do you feel there is excessive competitive attitudeamong students?

137 (63.72) 46 (62.16) 24 (60.00) 67 (66.34) 0.732

Do you feel there is unhealthy peer rivalry andjealousy among students?

127 (59.06) 37 (50.00) 20 (50.00) 70 (69.31) 0.015

Do you feel the situation in the campus has becomeunhealthy due to excessive student politics?

174 (80.93) 58 (78.38) 38 (95.00) 78 (77.23) 0.030

Are you involved in a serious romantic relationship? 85 (39.53) 22 (29.73) 15 (37.50) 48 (47.52) 0.057

Are you satised with the social life/recreational

activities in college campus?

84 (39.06) 27 (36.49) 15 (37.50) 42 (41.58) 0.794

ThePvalue in the last column is from comparison between the three semesters by Fishers exact test (with Freeman-Haltonextension)

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjmedsci.org on Saturday, January 02, 2016, IP: 125.161.213.32]

-

7/24/2019 IndianJMedSci6611-3703196_101711

6/12

6 INDIAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 66, No. 1 and 2, January and February 2012

likely than urban students to be staying in

hostel (P< 0.001), coming from a vernacular

medium background (P< 0.001), and belonging

to low-income families (P= 0.007), although

they did not feel that these factors impacted

their performance more than their urban

counterparts (32.63% for rural vs. 25.00% for

urban,P= 0.227).

On analyzing the GHQ-28 scores of the three

semesters separately, 35 students of 3 rd

semester (47.30%), 24 of 6thsemester (60.0%),

and 54 of 9 th semester (53.47%) scored

5 or more by bi-modal method. So a total

of 113 (52.56%; 95% CI 43.35-61.76%)students scored in the positive range of

stress by GHQ-28. Although the percentage

of stressed students in each semester was

quite high, there was no statistically signicant

difference in stress incidence on comparing

the three semesters (P= 0.480). By the same

parameter, 50% of the male respondents and

60% of the female respondents were stressed,

though this observed difference was not

statistically signicant (P= 0.214). As depicted

in Table 3, there was also no statistically

signicant difference in the incidence of stress

by the other baseline characteristics, with the

incidence being approximately 50% in each of

the baseline subgroups.

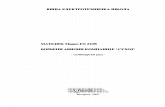

The numerical scores obtained by the various

instruments are summarized in Table 4.

With the exception of GHQ-28 anxiety

subscale score, which peaked in the final

semester and the LSNS-R friend component

score, which was least in the 6th semester,

there was no difference in scores across the

three semesters. There was no gender wise

difference in GHQ-28, WEMWBS, or R-LSNS

scores. There was also no signicant difference

in scores by ruralurban background, by hostel

versus home stay, low-versus high-income

families, and sibling status. In the R-LSNS

ratings, respondents who had studied in a

vernacular medium had higher median scorefor the family component and lower score

for the friends component than their urban

counterparts, and these differences were

statistically signicant (P= 0.014 and 0.040,

respectively). However, the median total scores

were comparable (P= 0.663).

Finally, Table 5 summarizes the scores

obtained by stressed and non-stressed study

participants on the WEMWBS and revised

LSNS-R. As expected, the mental well-being

and social networking of stressed respondents

suffered in comparison to the non-stressed

students. Also, as expected, GHQ-28 total

score showed strong but negative correlation

Table 3: Frequency of stress occurrence (by score >4 on 28-item General Health Questionnaire) in various

baseline subgroups

Subgroup Number stressed (%) Subgroup Number stressed (%) P value

Male (n=160) 80 (50.00) Female (n=55) 33 (50.00) 0.214

Rural background (n=95) 54 (56.84) Urban background (n=120) 59 (49.17) 0.275

Staying in hostel (n=152) 81 (53.29) Staying at home (n=63) 32 (50.79) 0.766

Vernacularmedium (n=129)

45 (52.33) English medium (n=86) 68 (52.71) 1.000

Low-income family (n=53) 27 (50.94) Low-income family (n=162) 86 (53.09) 0.874

No siblings at home (n=66) 32 (48.48) Siblings at home (n=149) 81 (54.36) 0.461

ThePvalue in the last column is from comparison between the two subgroups concerned by Fishers exact test

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjmedsci.org on Saturday, January 02, 2016, IP: 125.161.213.32]

-

7/24/2019 IndianJMedSci6611-3703196_101711

7/12

7STRESS IN MEDICAL STUDENTS

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 66, No. 1 and 2, January and February 2012

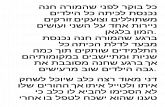

with the WEMWBS in the study cohort as a

whole [Figure 1] (Spearmans rank correlation

coefficient 8.21), although the correlation

with LSNS-R score was poor (Spearmans

rank correlation coefcient 3.11). There wasdirect and good correlation (Spearmans rank

correlation coefcient 5.04) between mental

well-being and social networking scores.

DISCUSSION

Assessing the stress burden in medical

students is important and such assessment

would be the rst step towards institution of

remedial measures. There is increasing interest

in the concept of positive mental health and

its contribution to all aspects of human life.

The World Health Organization has declared

positive mental health to be the foundation for

well-being and effective functioning for both

the individual and the community and dened

it as a state which allows individuals to realize

Table 4: Summary of scores obtained by study cohort on various study instruments

Scale Overall(n=215)

Semester 3(n=74)

Semester 6(n=40)

Semester 9(n=101)

P value

GHQ-28 somatic subscale score 2.01.98 2.02.09 1.0 1.51.58 2.12.02 0.223

1.0 (0.0-3.0) (0.0-3.0) 1.0 (0.0-2.0) 2.0 (0.0-4.0)

GHQ-28 anxiety subscale score 2.62.23 2.12.00 2.42.07 3.02.38 0.035

2.0 (1.0-4.0) 2.0 (0.0-4.0) 2.0 (1.0-4.0) 3.0 (1.0-5.0)

GHQ-28 social dysfunction subscale score 1.91.84 1.61.45 2.31.97 2.02.00 0.364

1.0 (0.0-3.0) 1.0 (0.5-2.0) 2.0 (0.5-4.0) 1.0 (0.0-3.0)

GHQ-28 depression subscale score 1.11.57 0.91.34 1.51.89 1.11.59 0.495

0.0 (0.0-2.0) 0.0 (0.0-1.0) 1.0 (0.0-2.5) 0.0 (0.0-2.0)

GHQ-28 total score 7.45.87 6.55.17 7.65.91 8.16.29 0.398

6.0 (2.0-12.0) 5.0 (3.0-8.0) 7.5 (2.0-11.5) 6.0 (2.0-13.0)

Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale 50.310.92 50.79.24 47.89.87 51.012.33 0.093

51.0(44.0-58.0)

51.0(45.0-56.0)

49.0(42.0-54.0)

53.0(44.0-59.0)

Revised Lubben social network scale-familycomponent score

14.56.16 15.06.98 14.55.39 14.25.85 0.573

14.0

(11.0-19.0)

16.0

(9.0-20.0)

14.0

(11.0-19.0)

14.0

(11.0-17.0)Revised Lubben social network scale-friendscomponent score

18.05.89 19.95.13 16.76.4 17.25.90 0.005

18.0(15.0-22.0)

20.5(17.0-24.0)

18.0(12.0-21.0)

17.0(13.5-21.0)

Revised Lubben social network scale-totalscore

32.59.88 34.810.33 31.110.16 31.49.22 0.073

32.0(26.0-39.0)

35.5(27.0-43.0)

33.0(24.0-40.0)

31.0(27.0-37.0)

GHQ-28=General health questionnaire-28-item version, Values depict meanstandard deviation and median (interquartile range),TheP valuein the last column is from comparison between the three semesters by Kruskal-Wallis test

Table 5: Comparison of scores obtained by

stressed (by score >4 on 28-item General Health

Questionnaire) and non-stressed study participants

Specifc question Stressed(n=113)

Non-stressed(n=102)

P value

Warwick-Edinburgh mentalwell-being scale

46.610.78 54.49.59

-

7/24/2019 IndianJMedSci6611-3703196_101711

8/12

8 INDIAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 66, No. 1 and 2, January and February 2012

their abilities, cope with the normal stresses of

life, work productively and fruitfully, and make

a contribution to their community.[24,25] The

capacity for mutually satisfying and enduring

relationships is another important aspect of

positive mental health. Therefore in our study,

we assessed the stress burden in conjunction

with mental well-being and social networking.

There is no single universally accepted

instrument to quantify stress in medical

students. In addition to GHQ-28, various

other rating scales have been used, such as

the medical student stress prole[26] and the

Maslach burnout inventory-student survey.[27]

However, the later scales have not been

used widely in different sociocultural contexts.

Biomarkers have also been employed, such

as blood pressure, salivary cortisol, circulating

cytokines, and sperm count, but these are more

in the context of acutely stressful events such

as impending examinations.[12,28-30]

We therefore

settled for GHQ-28 which is not restrictive

to the context of an individual being solely a

medical student rather than a member of the

community in general. The GHQ is actually

available in multiple versions including 12,

28, 30, or 60 items. The 28-item version is

used most widely. This is not only because

of time considerations but also because

it has been used most widely in various

working populations, allowing for more valid

comparisons.

We included three different semesters

in our study as our intention was also to

examine whether the magnitude or profile

of stress change with advancement of the

academic career through predominantly

pre-cl in ical (3 rd semester 2 nd year),

mixed (6 th semester 3 rd year) , and

predominantly clinical (9thsemester 5thyear)

involvements. First-year medical students were

deliberately left out as we felt that they were

yet to be exposed to the full extent of the stressburden and were unlikely to have evolved

personal coping strategies. As it turned out, the

extent of stress and the possible determinants

appeared to be uniformly distributed for

students of all three semesters, unlike in an

earlier Indian study where stress was more

in the latter years compared to the 1styear of

study.[14]

This questionnaire-based survey revealed

a high rate of stress and emotional distress

in medical students, affecting 52.56% of

those studied. An earlier study on Indian

medical undergraduates, published more

than 10 years back, had revealed stress in an

even higher proportion (73%) of students. [14]

Studies from Iran[31]

and Saudi Arabia[32]

report

Figure 1: Scatter plot depicting correlation between28- i tem Genera l Hea l th Ques t ionna i re and

WarwickEdinburgh mental well-being scale scores inthe study cohort. The regression line is shown

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjmedsci.org on Saturday, January 02, 2016, IP: 125.161.213.32]

-

7/24/2019 IndianJMedSci6611-3703196_101711

9/12

9STRESS IN MEDICAL STUDENTS

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 66, No. 1 and 2, January and February 2012

stress in over 60% of respondents. An US

study suggested psychiatric illness in 15-20%

of medical students needing some kind of

medical intervention.[33] A study on British

medical students, reported an incidence of

emotional disturbances in 31.2% of students.[34]

Some other studies have also revealed high

prevalence of depression and anxiety among

medical students, with levels of overall

psychological distress consistently higher than

in the general population.[4-8]

A higher percentage of female students

confessed to have stress compared to their

male counterparts, though the difference was

not statistically signicant. Some other studies

have also revealed higher prevalence of stress

in female students,[32-35] though the previously

mentioned Indian study does not reveal any

gender predilection.[14]Higher prevalence of

stress in female students could be due to their

experience of working in an environment still

largely populated by men than women, thoughthis scenario has changed considerably over

the years.

The possible inducers of stress in medical

students could be infrastructural factors such

as unsatisfactory living conditions in the hostel

and inadequate library facilities, academic

factors such as pressure of studies and

frequent examinations, and interpersonal

factors such as excessive competitive attitude

among students, political conicts, and jealousy

and peer rivalry over love affairs, all of which

could come in the way of natural friendship

and cooperation. Limited data are available

regarding the exact contribution of these

factors to student distress and its impact on

academic performance, dropout rates, and

professional development. [1,36] Low-income

family is another factor and socioeconomic

disparity among students, whether real or

perceived, could add to the difculties and the

emotional turmoil. However, it is noteworthy

that the extent of stress appeared to remain

at the same level in all the subgroups in our

study based on presence and absence of

these individual stressors. Such wide range of

stressors and additional ones have also been

reported in earlier studies. In a recent survey

on seven US medical schools, the authors

found a distinct relationship between pass/fail

grading and curriculum structure with well-being

among pre-clinical medical students.[37] The

British study identied talking to patients and

presenting cases, dealing with death and

suffering, and relationship with consultants

as common factors inducing stress in medical

students.[34]

Stress in medical students can have

professional ramications, including damagingeffects on empathy, ethical conduct, and

professional ism, as wel l as personal

consequences such as substance abuse,

burnouts, broken relationships, and suicidal

ideation. Therefore, it is the responsibility of

the society in general and medical schools

in particular, to acknowledge stress among

future doctors, identify sources of stress,

assess the individual students coping ability,

and undertake alleviatory measures.[38] Some

of the suggested stress reducing measures

could be improving the living conditions

and infrastructural facilities available to

students; reducing the incidence of campus

conicts; giving more importance to ongoing

academic performance rather than on marks

obtained in summative evaluations; and

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjmedsci.org on Saturday, January 02, 2016, IP: 125.161.213.32]

-

7/24/2019 IndianJMedSci6611-3703196_101711

10/12

10 INDIAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 66, No. 1 and 2, January and February 2012

ensuring availability of well-trained student

counselors and specic programs to promote

stress resilience and self-care in medical

students. [2,4,6,39,40] Our study revealed a

direct correlation between mental well-being

and social networking scores. Therefore,

encouraging measures to improve social

networking on campus, such as college

festivals and sports, are also important

stress-alleviating measures. Efforts to reduce

student distress should be viewed as an

essential component of broader programs to

promote overall student well-being.

Our study has its share of shortcomings.

Although we included over 40% of the students

currently on our institutions rolls, conducting

the study as a multicentric survey would have

improved the generalizability of the ndings.

We were unfortunate that on the particular

survey date, we could obtain analyzable data

from

-

7/24/2019 IndianJMedSci6611-3703196_101711

11/12

11STRESS IN MEDICAL STUDENTS

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 66, No. 1 and 2, January and February 2012

2006;81:354-73.

2. Al-Dubai SA, Al-Naggar RA, Alshagga MA,

Rampal KG. Stress and coping strategies of

students in a medical faculty in Malaysia. Malays

J Med Sci 2011;18:57-64.

3. Dahlin M, Nilsson C, Stotzer E, Runeson B. Mental

distress, alcohol use and help-seeking among

medical and business students: A cross-sectional

comparative study. BMC Med Educ 2011;11:92.

4. Jurkat HB, Richter L, Cramer M, Vetter A,

Bedau S, Leweke F, et al. Depression and stress

management in medical students. A comparative

study between freshman and advanced medical

students. Nervenarzt 2011;82:646-52.

5. Haight SJ, Chibnall JT, Schindler DL, Slavin SJ.

Associations of medical student personality and

health/wellness characteristics with their medical

school performance across the curriculum. Acad

Med 2012;87:476-85.

6. Park J, Chung S, An H, Park S, Lee C, Kim SY,

et al. A structural model of stress, motivation,

and academic performance in medical students.

Psychiatry Investig 2012;9:143-9.

7. Prinz P, Hertrich K, Hirschfelder U, de Zwaan M.

Burnout, depression and depersonalisation-Psychological factors and coping strategies in

dental and medical students. GMS Z Med Ausbild

2012;29.

8. Fan AP, Kosik RO, Su TP, Lee FY, Hou MC,

Chen YA, et al. Factors associated with suicidal

ideation in Taiwanese medical students. Med

Teach 2011;33:256-7.

9. A l -Dabal BK, Koura MR, Rasheed P,

Al-Sowielem L, Makki SM. A comparative studyof perceived stress among female medical and

non-medical university students in Dammam,

Saudi Arabia. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J

2010;10:231-40.

10. Hsieh YH, Hsu CY, Liu CY, Huang TL. The levels of

stress and depression among interns and clerks in

three medical centers in Taiwan: A cross-sectional

study. Chang Gung Med J 2011;34:278-85.

11. Behere SP, Yadav R, Behere PB. A comparative

study of stress among students of medicine,

engineering, and nursing. Indian J Psychol Med

2011;33:145-8.

12. Khaliq F, Gupta K, Singh P. Stress, autonomic

react iv i ty and b lood pressure among

undergraduate medical students. JNMA J Nepal

Med Assoc 2010;49:14-8.

13. Nagpal SJ, Venkatraman A. Mental stress among

medical students. Natl Med J India 2010;23:106-7.

14. Supe AN. A study of stress in medical students

at Seth G. S. Medical College. J Postgrad Med

1998;44:1-6.

15. Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the

General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med

1979;9:139-45.

16. Jackson C. The General Health Questionnaire.

Occup Med 2007;57:59.

17. Guthrie EA, Black D, Shaw CM, Hamilton J,

Creed FH, Tomenson B, et al. Embarking upon

a medical career: Psychological morbidity in rst

year medical students. Med Educ 1995;29:337-41.

18. Nagyova I, Krol B, Szilasiova A, Stewart RE,

van Djik JP, van den Heuval WJA. General Health

Questionnaire-28: Psychometric evaluation

of the Slovak version. Studio Pysholoiga2000;42:351-61.

19. Shariati M, Yunesian M, Vash JH. Mental health

of medical students: A cross-sectional study in

Tehran. Psychol Rep 2007;100:346-54.

20. Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, Platt S, Joseph S,

Weich S, et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental

well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development

and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes

2007;5:63.21. Stewart-Brown S, Tennant A, Tennant R, Platt S,

Parkinson J, Weich S, et al. Internal construct

validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being

scale (WEMWBS): A Rasch analysis using data

from the Scottish health education population

survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:15.

22. Lubben J, Gironda M. Measuring social networks

and assessing their benets. In: Phillipson C,

Allan G, Morgan D, editors. Social networks

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjmedsci.org on Saturday, January 02, 2016, IP: 125.161.213.32]

-

7/24/2019 IndianJMedSci6611-3703196_101711

12/12

12 INDIAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Indian Journal of Medical Sciences Vol 66 No 1 and 2 January and February 2012

and Social exclusion: Sociological and policy

perspectives. Farnham, Surrey, United Kingdom:

Ashgate Publishing Limited; 2004. p. 20-35.

23. Rubinstein RL, Lubben JE, Mintzer JE. Social

isolation and social support: An applied

perspective. J App Gerontol 1994;13:58-72.

24. Herman H, Saxena S, Moodie R, edi tors.

Promoting Mental Health: Concepts-emerging

evidence-practice: Summary Report. Geneva:

Department of mental health and substance abuse,

world health organization; 2004. Available from:

http://www.who.int/mental health/evidence/en/

promoting mhh.pdf. [Last accessed on 2012 Sep 3].

25. World Health Organization. Strengthening

mental health promotion [Fact Sheet No. 220],

2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/

mediacentre/factsheets/fs220/en. [Last accessed

on 2012 Sep 3].

26. ORourke M, Hammond S, OFlynn S, Boylan G.

The medical student stress prole: A tool for

stress audit in medical training. Med Educ

2010;44:1027-37.

27. Galn F, Sanmartn A, Polo J, Giner L. Burnout

risk in medical students in Spain using the

maslach burnout inventory-student survey. Int

Arch Occup Environ Health 2011;84:453-9.

28. Hulme PA, French JA, Agrawal S. Changes in

diurnal salivary cortisol levels in response to an

acute stressor in healthy young adults. J Am

Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 2011;17:339-49.

29. Kamezaki Y, Katsuura S, Kuwano Y, Tanahashi T,

Rokutan K. Circulating cytokine signatures in

healthy medical students exposed to academic

examinat ion st ress. Psychophysio logy

2012;49:991-7.

30. Lampiao F. Variation of semen parameters in

healthy medical students due to exam stress.

Malawi Med J 2009;21:166-7.

31. Koochaki GM, Charkazi A, Hasanzadeh A,

Saedani M, Qorbani M, Marjani A. Prevalence

of stress among Iranian medical students:

A questionnaire survey. East Mediterr Health J

2011;17:593-8.

32. Abdulghani HM, AlKanhal AA, Mahmoud ES,

Ponnamperuma GG, Alfaris EA. Stress and its

effects on medical students: A cross-sectional

study at a college of medicine in Saudi Arabia.

J Health Popul Nutr 2011;29:516-22.

33. Lloyd C, Gartrell NK. Psychiatric symptoms

in medical students. Compr Psychiatry

1984;25:552-65.

34. Firth J. Levels and sources of stress in medical

students. Br Med J 1986;292:1177-80.

35. Backovi DV, Zivojinovi JI, Maksimovi J,

Maksimovi M. Gender differences in academic

stress and burnout among medical students

in final years of education. Psychiatr Danub

2012;24:175-81.36. Dyrbye LN, Harper W, Durning SJ, Moutier C,

Thomas MR, Massie FS Jr, et al. Patterns of

distress in US medical students. Med Teach

2011;33:834-9.

37. Reed DA, Shanafelt TD, Satele DW, Power DV,

Eacker A, Harper W, et al. Relationship of

pass/fail grading and curriculum structure

with well-being among preclinical medical

students: A multi-institutional study. Acad Med2011;86:1367-73.

38. Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Commentary: Medical

student distress: A call to action. Acad Med

2011;86:801-3.

39. Jurkat H, Hfer S, Richter L, Cramer M, Vetter A.

Quality of life, stress management and health

promotion in medical and dental students.

A comparative study. Dtsch Med Wochenschr

2011;136:1245-50.40. Thomas SE, Haney MK, Pelic CM, Shaw D,

Wong JG. Developing a program to promote

stress resilience and selfcare in rstyear medical

students. Can Med Educ J 2011;2:e32-6.

How to cite this article:Nandi M, Hazra A, Sarkar S, MondalR, Ghosal MK. Stress and its risk factors in medical students: Anobservational study from a medical college in India. Indian J MedSci 2012;66:1-12.Source of Support: Nil. Conict of Interest:None declared.

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjmedsci.org on Saturday, January 02, 2016, IP: 125.161.213.32]