3179972

-

Upload

marinavidenovic -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

0

Transcript of 3179972

-

8/4/2019 3179972

1/20

A Developmental Method to Analyze the Personal Meaning Adolescents

Make of Risk and Relationship: The Case of Drinking

Robert L. SelmanHarvard University

Cambridge, MA

Sigrun AdalbjarnardottirUniversity of Iceland

Ber er hver a baki, nema sr brur eigi.(Ones back is bare without a brother.)

Njals Saga, 13th century

Thegoal of this article is to demonstrate theapplication of a psychosocial developmen-tal frameworkandinterpretive method ofanalysistodata gathered throughin-depthinterviews. The article applies this analysis in the context of a case comparative design,

drawing on interviews with two 15-year-old Icelandic boys who drank alcohol fre-quently,but in different waysand withdifferent consequences.Thisarticle describes theutility of a developmental approach to the analysis of the risks adolescents take, espe-cially to their health.It illuminates theparallels betweenthelevels ofawareness individ-uals have of the risks they take, and the quality of the meaning they make of their closesocial relationships. It demonstrates therolea cultural perspective plays in thedevelop-mental interpretation of the data. Finally, the article touches on the implications of thiskind of analysis for psychosocial prevention practices and policies.

The Parameters of the Problem

Im not worried about getting to be an alcoholic.If it comes a time I think I cant stop drinking,when its no more fun, thats when Ill stop. Mydad drank for about 15 years, even got drunk alot, but when the doctor put him in the hospitaland said hewould reallyget sickor even die ifhekeptdrinking,hestopped.Ifhecanstopanytime,so can I. (Gunnar, age 15; Reykjavik, Iceland)

If I becameanalcoholic, I would make the de-cision to stop. Naturally, however, it is harder tomake that decision if you are an alcoholic. But Icould for sure now. My father stopped drinking[because] he is an alcoholic, but he is verystrong-willed. I am notsure I am as strong-willed

yet,butmaybeIwillbemorelikemymother.She

drinks in moderation and I intend to drink inmoderation as well when I grow up. (Bjorn, alsoage 15; also from Reykjavik)

By the age of 15, almost all teenagersmanythrough firsthand experience, others through familyhistory, courses in school, or messages from the me-diaknow the risks of drinking alcohol. They knowthat alcohol can be highly addictive. They know it canhave powerful effects on social judgment and physicalcoordination. They know that excessive drinking canbe quite harmful to mental as well as physical health;they know that alcoholism puts families at risk, eco-nomically as well as psychologically. Yet, over thecourse of the past 50 years teenagers have begun todrink more often, and at an earlier age; and, more re-

cently, the number of younger girls who drink has beenon the rise (Johnson & Gerstein, 1998; Johnston,OMalley, & Bachman, 1995).

Why, if society publicizes the many risks of heavydrinking, do increasing numbers of adolescents chooseto take these risks?What accounts for this seeming gapbetween their knowledge of potential dangers to theirhealth and well-being, and their risk-taking behav-iorbetween awareness and action?

We believe that a developmental framework andmethodology, based on listening closely and carefully

47

Applied Developmental Science Copyright 2000 by2000, Vol. 4, No. 1, 4765 Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

We received the following support for this article: to Robert L.Selman, grantsfromthe Spencer, W.T. Grant,and Carnegie Founda-tions and a Fulbright Senior Scholar award; to SigrunAdalbjarnardottir, grants from the Icelandic National Science Foun-dation and theResearch Foundation of theUniversity of Iceland. Thelatter foundations also supported the research project under Dr.Adalbjarnardottirs direction from which we drew the case materialpresented and discussed here.

RequestsforreprintsshouldbesenttoRobertL.Selman,HarvardUniversity, Graduate School of Education, 609 Larsen Hall, AppianWay, Cambridge, MA 02138.

-

8/4/2019 3179972

2/20

towhatteenagersthemselveshavetosay,canprovideuswithnewinsightsaboutadolescentrisk-takingbehaviorin general and, in this case, the problem of adolescentdrinking. Therefore, we focus this article on our meth-odologyandspeaktoitsutilityforresearchandtouchonits implications for practice. This article marks the firstpublishedillustrationofthisnewqualitativemethod.By

new, we mean the integration of our previous man-ual-based method to analyze developmentally the per-sonal meaning of health risks (e.g., Levitt & Selman,1996), with our manual-based research on thedevelop-mental analyses of perspectives on close personal rela-tionships (e.g., Adalbjarnardottir & Selman, 1989;Selman, 1980). In essence, we describe a replicable sci-entific methodforasking questionsof youth,anda wayto listen to and code their responses.

For example, at first glance, the comments of Gun-nar andBjorn quotedpreviously might seem quite sim-ilar. But there are significant differences betweenthem, and these point to what we maintain are impor-

tant developmental differences in the ways these twoadolescents understand and respond to the pleasuresand risks of drinking. Before we consider the cases ofGunnar and Bjorn in depth, as reflected by these andother statements they made when interviewed in Reyk-javik, Iceland, we need to put their words in theoreti-cal, empirical, and historical context.

Theoretical Perspectives on Adolescent

Risk-Taking

There is much at stake here. For example, in thecase of alcoholic drinking, epidemiological studies

show that the earlier in life an individual starts drink-ing, the more likely he or she is to have serious prob-lems managing alcohol later in life (Kandel,Yamaguchi, & Chen, 1992; Robins & Przybeck, 1985;Stacy, Newcomb, & Bentler, 1993). Other studies re-veal a strong connection between the early onset ofheavy drinking, theabuse of other drugs, andantisocialbehaviors like vandalism, theft, and violence (Brook,Cohen, & Brook, 1998; Donnermeyer, 1992;Ellickson, Hays, & Bell, 1992; Kandel et al., 1997;Loeber, 1988). And, of course, underage drinking isassociated with educational problems, such as poorschool performance or dropping out of school, whichhave serious long-term consequences for both the indi-vidual and society as a whole (e.g., Boyd, Howard, &Zucker, 1995; Cairns & Cairns, 1994; Irwin, 1993).

Social scientists do not lack for theories into whyearly adolescents (ages 1015) choose to engage inrisky activities in the face of the clear-cut knowledgethey possess of the potential harm to their well-being(Buchanan, 19901991; Helweg-Larsen & Collins,1997; Johnston & OMalley, 1986; Nichter, Vukovic,Quintero, & Ritenbaugh, 1997). Over thepast 50 years,theoristswhofocus on thepsychology of the individual

have proposed a seriesof explanations for theoften ob-servedgapbetweentherelativematurityofadolescentssocial thought and the variable maturity of their socialaction. These explanations range from an immature orundeveloped future time perspective, the supposedtunnelvisionofyouth,anaturalornativerebellious-ness against authority and society (Erikson,

1950/1963,1968),toalibido-drivenquasi-regressiontoan adolescent form of egocentrism (Arnett, 1995;Elkind, 1974; Greene, Rubin, Hale, & Walters, 1996).They point out that, of course, adolescents understandthe dangers of health risks like smoking or drink-ingthey simply believe they can quit these habits be-fore they do themselves serious or permanent harm(Brook, Whiteman, Cohen, & Shapiro, 1995; U.S. De-partment of Health and Human Services, 1994).

Other observers have pointed out that for some ado-lescents it may not be the case that they are unable toconsider the power of psychological or physical addic-tion or the future costs of smoking or drinking to ex-

cess. It may simply be easier for adolescents to weighlightly the far-off, future risks of smoking or excessivedrinking because they value highly the immediate ben-efits they receive from these activities in the present(Burton, Sussman, Hansen, Johnson, & Flay, 1989).Finding ways to manage unruly, newly felt, and pow-erful feelings of sexual attraction, or to fulfill the ur-gent need to be included in, or lead, a particular socialgroup, tops the to-do list of many adolescents. Ifsmoking or drinking, in addition to providing stimula-tion, relaxation, or distraction, helps to facilitate theseroles and relationships, so much the better. It is notsimply because they think they are invulnerable in the

future that adolescents take these risks with theirhealth. It is because they are determined to do whatthey perceive as necessary to thrive in the present (Ep-stein, Botvin, Diaz, & Schinke, 1995).

Observers of adolescence from other social sciencedisciplines have focused their inquiries beyond thelevel of the single individuals actions. They are lesslikely to locate the primary explanations for behaviordangerous to personal health in the developing psycheof an individual and more likely to look to the natureand dynamics of the social groups to which adoles-cents belong and bond (Bahr, Marcos, & Maughan,1995; Flannery, Vazsonyi, Torquati, & Fridrich, 1994;Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992). From the point ofview of a social psychologist, resistance to societalknowledge is seen as a transition marker, a means bywhich adolescents make a claim on maturity throughtheir individual lifestyle choices (Jessor, 1998; Jessor& Jessor, 1977). The emphasis at this level of analysisis on the importance to adolescents, in particular, offeeling a sense of belonging, of being part of a mutu-ally supportive peer group. When mutual support ex-ists, there is a decrease in potentially harmfulrisk-taking among all members of the group (McBride

48

SELMAN AND ADALBJARNARDOTTIR

-

8/4/2019 3179972

3/20

et al., 1995). Weak social and community bonds, onthe other hand, release adolescents from group normsthat discouraged negative risk-taking behaviors(Duncan, Tildesley, Duncan, & Hops, 1995; Krohn,Massey, Skinner, & Laurer, 1983).

Beyond the dynamic but subtle influences of socialgroupings on individual adolescents, are the even less

tangible, but no less powerful, cultural currents withinwhich these individuals and groups operate. Over thelast 30 years, social scientists have gained a muchbetter understanding of how cultural diversity, within,as well as across national boundaries, influences ado-lescent identity development (Cooper, 1999; Garrod,Smulyan, Powers, & Kilkenny, 1992; Hurrelmann &Hamilton, 1996; Lightfoot, 1997). We have becomeincreasingly aware of the importance that membershipin an identifiable cultural group has for the interpreta-tions that adolescents make of behaviors that may af-fect their health (Brannock, Schandler, & Oncley,1990; Way, 1998). For some adolescents, membership

may come thorough entry into an affinity group with areputation for being on the experimental edge of sub-stance use (Jessor, 1992, 1993). Or, it may mean per-sonal identification with an ethnic background thatincludes a long-standing tradition of embracingcertainkinds of risky behaviors, like drinking whisky orsmoking cigarettes (Earls, 1993).

Over the last several decades, large-scale nationalsurveys in the United States and Europe have docu-mented the changing behavior patterns of adolescentsfromdifferent backgrounds toward cigarettesand alco-hol as well as other potentially addictive and harmfulsubstances (Institute for Health Policy, Brandeis Uni-

versity, 1993; Partnership for a Drug Free America,1997; U.S. Department of HealthandHuman Services,1994). For instance, in Iceland, the site of this study, byage 15, drinking prevalence rates have increased from25% in the 1970s to above 75% currently, among teen-age girls (Adalbjarnardottir, Davidsdottir, &Runarsdottir, 1997; Olafsdottir, 1982). In the UnitedStates, the smoking prevalence rates among AfricanAmericanninth-gradeyouthhave increasedfrom6.6%in 1992 to 12.2% in 1996 (U.S. Department of HealthandHuman Services, 1998). Whyhave these particularcultural groups shifted their attitudes toward thesehealthrisks?We donot have enoughinformation topro-vide an answer, but the results of these surveys havedemonstrated that we should indeed take seriouslycul-tural factors, especially ethnicity and gender, in our at-tempt to understand risk-taking among adolescents.

Although surveys contributeneeded information bydocumenting trends in adolescent attitudes and behav-iors, they alone cannot detect the deeper developmen-tal and cultural foundations in meanings that underlieattitudes and actions. For example, a survey can indi-cate that middle-classgirls smoke because they believeit will keep down their weight and help them deal with

interpersonal conflicts. But why, in both a develop-mental and cultural sense, do they think it personallymeaningful to control either their weight or their emo-tions? Surveys do not tell us what adolescents them-selves can tell us, if only we ask them to take seriouslyquestions that probe the deeply embedded psychologi-cal, social, and cultural meanings that lie just under the

surface of their attitudes and actions.Our review makes it clear that there can be no sim-ple single discipline explanation for the fact thatmany adolescents drink to excess in spite of theirknowledgethat doing so is dangerous. Because teenag-ers act not only as individuals, but also as members ofparticular peer groups, communities, and different cul-tures, the task of understanding excessive teenagedrinking, and of devising ways to combat it, calls forinnovative approaches that can integrate and build onthe insights provided by many different social scienceperspectives (Jessor, 1998;Lerner, 1995;Schulenberg,Maggs, & Hurrelmann, 1997).

A Developmental Analysis of

Teenagers Perspectives on Drinking

That drinking has increased in recent years amongyounger adolescents, who in turn are more highly vul-nerable to lifelong addiction, strongly suggests weneed a more adequate scientific knowledge base onwhich to build more effective prevention practices andpolicies. For such purposes, it would be useful to inte-grate the collection of data about actual behavior withmethods that interpret the adolescents awareness ofthe feelings and motivations behind that behavior. To

do so, we need to engage in serious conversations overtime with diverse samples of adolescents. Recent sys-tematic in-depth psychological interview research hasdescribedwhat adolescents have to say about how theyconnect the health risks they face to their social and so-cietal relationships (Berkowitz, Begun, Zweben, &James, 1995; Brown & Gilligan, 1992; Feldman &Elliott, 1990).

Muchof this recent qualitative in-depth psychologi-cal research has oriented toward thecontent analysis ofthe different themes adolescents raise in their reflec-tions on risky experiences and close relationships(Giese, 1998; Lightfoot, 1997; Way, 1998). In this arti-cle, we describe how we applied a developmental anal-ysis to these themes and issues. Our methodologyrelies on in-depth interviews with teenagers, in whichwe ask a number of structured and open-ended ques-tions, and then listen carefully to their responses, bothdevelopmentally and thematically. We believed that adevelopmental analysis can make an important contri-bution to the way we ask questions of adolescents. Italso provides a way to listen to what adolescents sayabout the complexity of their social lives and the riskychoices they face in these contexts.

49

RISK AND RELATIONSHIP IN ADOLESCENTS

-

8/4/2019 3179972

4/20

Basic Assumptions and a Brief

History of Our Approach

What do we mean by a developmental analysis? Forover 25 years, our Group for the Study of InterpersonalDevelopment (GSID) worked to construct an evolvingtheoretical framework to study the development of in-

dividuals perspectives on social relationships. Morerecently, we have focused our research on their per-spectives on risks (e.g., Levitt & Selman, 1996; Levitt,Selman, & Richmond, 1991). In the first phase of ourwork, we focused on the growth of childrens interper-sonal understanding, for example, on their developingconceptions of friendship or of peer relationships(Selman, 1980). Mapping the growth of interpersonalunderstanding also exposed a gap between this kind ofunderstanding and social behavior in manyyoungsters.We found we needed a theoretically consistent way todescribe the relations between levels of interpersonalthought and interpersonal action. In the second phase,

we incorporated a developmental analysis of chil-drens developing interpersonal negotiation skills (i.e.,thoughts about solving social conflicts) and interper-sonal negotiation strategies (i.e., observed strategiesfor dealing with issues of conflict and closeness). Wedid this work primarily in the complexity of real lifesocial contexts for intervention, for example, publicschools, after school programs, day and residentialtreatment (Adalbjarnardottir & Selman, 1989; Schultz& Selman, 1998; Selman and Schultz, 1990).

When we tried to promote childrens social growthas a means to prevent them from getting into positionsof isolation or alienation from others (e.g., through

counseling children in pairs) we found the need to in-clude a personal meaning component to build a strongtheoretical connection among levels of interpersonalunderstanding, skills, and action. For example, adoles-cents with both the understanding and skills to dealwith interpersonal conflict or to avoid fights, wouldfight because of the personal meaning fighting had forthem in a particular situation in a particular culturalcontext. In the third phase of this work (Selman, Levitt,& Schultz, 1997), we conceptualized a developmentalanalysis of adolescents awareness of the personalmeanings they make of risks they take (e.g., fighting).In this article, for the first time, we connect explicitlyour method for the analysis of the understanding, man-agement, and awareness of personal meaning that ado-lescents make of the risks they face (in this casedrinking) to their awareness of their relationships tofamily and close friends.

From the earliest construction of our framework,we have built on the foundations of the social philoso-phy of George Herbert Mead (1934) and the develop-mental epistemology of Jean Piaget (1932/1965), inthe latter case as translated into a developmental psy-chology of moral judgment by Lawrence Kohlberg

(1969).1 A basic assumption promoted by each of thesetheorists was that the developing human capacity tocoordinate ones own perspective and that of other(s)one of the most, if not the most, essential ingredient indetermining the quality of human social relationships.We believe social perspective coordination to be a uni-versal social competence that operates in all individu-

als similarly at its core, even if it manifests differentlyacross cultures. In fact, we assume we are more likelyto take healthy, rather than harmful, risks in life whenwe consider our choices through the increasingly mu-tual coordination of our own perspectives with thoseabout whom we care. These assumptions inform ourmethods of analysis and the following working hy-pothesis:

To the extent adolescents can develop perspec-tive on the complex connections between theirown biological, personal, and cultural relation-ship histories and their own individual health

choices in daily life, they are more likely to keepthemselves out of harms way.

Our Scientific Aim

Our primary aim in presenting our comparativeanalysis of these two cases is methodological: to dem-onstrate how to use our in-depth interview method andtheoretical risk-and-relationship framework. Throughour comparative analysis of the anatomical structureof two adolescents psychosocial development, we aimto demonstrate thekey role theability to coordinate theperspectives of others with ones own plays in the dy-

namics of health risks like teenage drinking. We em-bed the analysis in the human ecology of Iceland todemonstrate that a levels analysis focused on indi-viduals thoughts and actions can be interpreted mean-ingfully only in their cultural context. Thismeaning-centered approach to psychosocial develop-ment aims to illuminate how the way an individual

50

SELMAN AND ADALBJARNARDOTTIR

1Theother influentialsource ofthisworkis less well-known tode-

velopmental psychology, but familiar in the literature on preventionof poorhealth habituations:the health promotiondisease preventionhealth-policy framework of Julius B. Richmond (e.g., Richmond &Kotelchuck, 1984). Richmonds three-part heuristic model definesthree components necessary for effective psychosocial preventionand public health programs at the national level. These are an under-standing of the scientific knowledge base pertinent to the risk, a rep-ertoire of social strategies to deal with it nationally, and the politicalwill to carry an agenda forward. In Richmonds model, the organ-ism under examination is the nation and its health. The core opera-tion of the approach is the promotion (development) of an enlight-ened national perspective on health policy (e.g., the reduction in thepopulation of lung cancer due to habituation to smoking, etc.). In ef-fect, these three societal components, which also can be seen to bedevelopmental, are the sociological analogues to the threepsychosocial components (interpersonal understanding, interper-sonal strategies to managerisk,and theawareness of personal mean-ing) we use in our analysis at an individual psychological level.

-

8/4/2019 3179972

5/20

deals with risks to his or her health corresponds to thedevelopmental maturity of theway he or shedeals withmeaningful social relationships.

The Research Context and

Epidemiological Background

WenowturntoourinterviewswithGunnarandBjorn,the two boys whose comments introduced this article.These individuals participated in a longitudinal researchproject, The Reykjavik Adolescent Risk-Taking Studythat Sigrun Adalbjarnardottir designed and directed toshed light on the problems that teenage drug and alcoholabuse pose for Icelandic society (Adalbjarnardottir,Davidsdottir, & Runarsdottir, 1997;Adalbjarnardottir&Hafsteinsson, 1998). A highly homogeneous society byinternational standards, Iceland has a strong workingclassandlittleextremepovertyorwealth,andthereforearelativelymodest discrepancyamongthedifferentsocialclasses (Olafsson, 1990). At the time of the study, it

rankedamongthetopfivenationsoftheworldaccordingto such quality-of-lifemarkers as levelsof infantmortal-ity, life expectancy, life satisfaction, and literacy rates(Euromonitor, 1999a, 1999b; Olafsson, 1990, 1997;United Nations, 1997), as well as low unemploymentrates (International Labour Office, 1998). Iceland hasbeenabletomaintainaclosesenseofcommunity,itsownlanguage, and a sense of national identity. In some waysthen, this small nation does not face the same severity ofsocial problems that weigh heavily on many other coun-tries (Gunnlaugsson, 1998).

In fact, contrary to some stereotypes about northerncultures, Icelanders do not drink more alcohol per per-

sonthan inhabitants of most other countries. Among 37countries in EuropeandNorth andSouth America, Ice-land rates the fourth lowest in sold liters of alcohol perperson (Produktschap Voor Gedistilleerde Dranken,1995). According to a cross-national study of 24 Euro-pean countries, only NorwayandTurkey (most citizensof thelatter areMuslims,whosereligion prohibitsalco-hol) have lower rates of adolescent drinking at age 15thanIceland(Hibelletal.,1997).YetinIceland,aselse-where,timesarechanging.Overthepast30years,therehave been significant shifts in drinking patterns amongthe youth in Iceland. For example, a 1970 survey indi-cated that 39% of Icelands 15-year-old boys and 24%of its 15-year-old girls reported that they had trieddrinking. Only 10 years later, by 1980, this proportionhad risen to 80% for 15-year-old boys and, even moredramatically, to 76% for girls in this age range(Olafsdottir, 1982). Although rates of drinking among15-year-olds in Iceland have held relatively stable forthe last 15 years (Adalbjarnardottir et al., 1997), thereare indications of disturbing new drinking patternsamong Icelandic adolescents in the last decade that ap-pear to be related to other troubling behaviors(Adalbjarnardottir, Rafnsson, & Hafsteinsson, 1999).

On any given occasion, when 15-year-old Icelandicadolescents drink, they tend to drink more heavily thando their peers in most other European countries (Hibellet al., 1997). In addition, compared to adolescents inother European nations, both boys and girls in Icelandhave among the highest rates of getting into trouble(scuffles, unwanted and unprotected sex, as well as be-

ing victimized by robbery or theft) when under the in-fluence (Hibell et al., 1997). One of the two boys onwhom our discussion focuses fit this pattern of bingedrinking and problem social behavior; the other, whoalso drank regularly, did not binge nor did he bully oth-erswhendrunk.Whatmightaccountforthisdifference?

Basedontheresultsofasetofsurvey-typequestion-naires administered to the entire sample in the Reykja-vikAdolescent Risk-Taking Study, we selected a smallcohort of teenagers for in-depth interviews. In this, ourfirst report of the analyses from that smaller sample ofteenagers,wedescribeourmethodfortheinterpretationof our interviews with Gunnar and Bjorn, two of the

teenagers who reported they were frequent drinkers.

The Anatomy of

Psychosocial Competence:

A Developmental Analysis

The Interviews

Our comparative developmental analysis of Gun-nars and Bjorns attitudes and perceptions towarddrinking and toward relationships adapts and integratestwo distinct GSID in-depth interview protocols: the

RiskyBusiness Interview(e.g.,Levitt & Selman, 1993)andtheRelationshipInterview(e.g.,Schultz,1993).Wedesigned these interviews to study the psychosocialfoundations of any risky behavior and of any meaning-fulsocialrelationship.TheRiskyBusinessInterviewin-cludes standardized hypothetical dilemmas andopen-ended questions that address the specific risk weexamine (e.g.,fightingor smoking).Here,as noted,thatrisk is drinking alcohol. We structure the interviewquestions to focus, in turn, on three related functionalcapacities, or areas, which we call the understanding,management, andpersonalmeaning oftheriskybehav-ior.Theinterviewyieldsresponsesthatreflectthematu-rity of each of these three functional areas within theindividual.Toassessthisdegreeofmaturity,weanalyzeandclassify responses using a perspective coordinationanalysisorganizedby developmental levels. (SeeTable1 for the kinds of questions that guide the interview.)Each interview lasts from 1 to 2 hr, and each is tape re-corded and transcribed for in-depth developmental andthematic analysis.

The Relationship Interview reverses figure andground to study the particular risk under examinationin the broader context of the maturity of the adoles-

51

RISK AND RELATIONSHIP IN ADOLESCENTS

-

8/4/2019 3179972

6/20

cents reflections on the dynamics of his or her per-sonal relationshipsin the case of this study withparents and peers. It does so in two ways. First, we ex-plore the dynamics of these relationships by asking theadolescent how he or she shares personal experienceswith parents and peers, and how he or she understandsand deals with the kinds of conflicts that arise betweenthem. Second, unlike theRisky Business Interview, theRelationship Interview is relatively unstructured. Al-though the protocol contains standard questions to

keep the conversation on course (see Tables 2 and 3), itdoes not automatically probe for responses that we canfit into one or another level on a predetermined devel-opmental scale. The aim here is to encourage partici-pants to express spontaneously emerging personalthemes and to narrate concrete incidents in a particularrelationship. Put another way, this interview gauges anindividuals capacities for intimacy (shared experi-ence) and autonomy (interpersonal negotiation) inclose social relationships.

This means we use this second interview in aground-up ratherthan a top-down way. We want toallow meaningful themesrelated to the twokinds of so-cial relationships (here with parents andpeers), and thetwo kinds of interpersonal dynamics (intimacyclose-ness, autonomyconflict) to rise from the responses ofthe participants. The interview protocol encourages adiscussion of risky behaviorsin this case the heavyuseofalcoholtoemerge,butonlyinthecontextofthebroader conversation about closeness and conflict inmeaningful social relationships. Afterwe identify rela-tional themes, such as not wanting to be pushedaround or wanting to look cool in the eyes of thegroup, weapplyourdevelopmentalanalysis to theevi-

dence. We examine the form of negotiations adoles-cents report using and the level of self-awareness (per-sonal meaning) they make of these themes.

The Framework

Generally, we believe that adolescents are morelikely to take healthy rather than harmful risks in theirlives if they are able to coordinate their own perspec-tives with those of others about whom they care. Fur-

ther, we believe that this ability develops over time.More specifically, we theorize that an individualscoreoperational capacity to coordinate points of view to-ward in-common social experiences develops in recip-rocal interaction with each of the three distinct, butclosely related, psychosocial competencies we infor-mally identified earlier in the brief history of our pro-ject. We now formally introduce them:

1. The general level of understanding individualshave of the facts about the nature of the risk inthe context of social relationships.

2. The repertoire of interpersonal strategies indi-viduals have available to manage risks.

3. The self-awareness individuals have of the per-sonal meaning of the risks they take in connec-tion to the quality of the personal relationshipsthey maintain.

Examples of these connections between risks andrelationships abound. Among early adolescents theyinclude the risk of joining a gang, of repeatedly gettinginto physical fights, of smoking twopacks of cigarettesa day, of trying to do well in school or dropping out, of

52

SELMAN AND ADALBJARNARDOTTIR

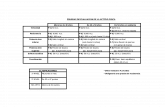

Table 1. The Risky Business Interview: Psychosocial Components, Issues, and Key Questions

Psychosocial Components Issues Key Questions

Understanding of the risk (here drinking) Initial (past) experiment Why do you think someone your age starts to drink beeror other alcoholic drinks?

Current purposes Why do people your age like to drink these days?Future consequences What can happen to people your age if they continue to

drink? Is it more difficult for some people to stop

drinking than others? Why?Interpersonal strategies (from hypothetical

dilemmas with parentsa and peersb)Definition of the problem What is the problem in this dilemma?Alternative strategies What are some ways they can solve these problems?Best strategy What is the best way to solve this problem?Evaluation How would they know the problem is solved?

Personal meaning of the risk Past motivation for experimenting When you first began drinking, why did you decide togive it a try?

Present atti tude What are the reasons for your drinking now?Future orientation Do you think at some time you might decide to change

yourdrinking habit? If youdecided tostopdrinking, doyouthinkyou couldstickto that decisionif youwantedto? How do you know?

aGunnar/Gudrungoestoapartyoneweekendeveningandcomeshomelateanddrunk. His/herdadiswaitingforhim/herwhenhe/shecomeshomeand is very angry. He tells Gunnar/Gudrun that he/she is to be grounded for a month. Gunnar/Gudrun feels this is too severe a penalty and that

he/she is old enough to decide for himself/herself whether he/she drinks or not. How can Gunnar/Gudrun deal with his/her father?bSee text for the dilemma between Jon and Dori.

-

8/4/2019 3179972

7/20

drinking and getting drunk.2 With respect topsychosocial functioning the mind is never static; it isalways acting within a particular social and culturalcontext. Although our model is structuralthat is, itrepresents development in terms of hierarchical levels,each level following and building on the one that camebeforeit is understood that few (if any) of us alwaysact in ways that represent thehighest level of compe-tence we are capable of bringing to bear on a given sit-uation. Nor does the model place greater importanceon the levelsof thought or actionexpressedin the inter-

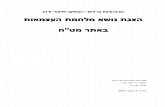

view than on its thematic content.Figure1 represents ourattempt todepictan anatomy

of psychosocial development. Looking down (i.e., top-ographically), thetop surface of thefigure describestheconnections between the core developmental capacitytocoordinatesocialperspectivesasitappliestothethreepsychosocial components of any given riskrelation-ship. From this birds eye view, the reciprocal arrowsacross areas highlight the transactional relationshipamongthepsychosocialcomponents(therelationofthethree areas of psychosocial functioning to each other).Arrowstoandfromthecenteremphasizetheconnectionof each area of functioning to the core developmentalcapacity to coordinate social perspectives.

TheconicalshapeofFigure1representsthedevelop-mental dimension of our conceptual picture. Thiscone-shaped aspect of the figure symbolizes the likeli-hood of increasing differentiation and integration ofpsychosocial functioning both within and across thethree areas withits developmentalaspect (theevolutionoflevelsofperspectivecoordinationwithintheindivid-ual). Following the approach of Heinz Werner (1948),this figure suggests that we can assess independentlyeach of the three psychosocial components along a de-velopmental continuum from immature (undifferenti-

ated and unintegrated) to mature levels (differentiatedandhierarchicallyintegrated).Byourstandards,thepo-tential for growth in an individualspsychosocial func-tioningisdirectlyrelatedtothatindividualscapacitytoputintoperspective therisksheor shemustconfront andthe relationships he or she holds as important.

We realize that for these theoretical terms to bemeaningful, we must describe in concrete and reliablymeasurabletermsthewayeachlevelinthecoordinationof social perspectives manifests itself in each area ofpsychosocialcompetence. By knowing in detailthe de-velopmental characteristicsof each of thethreeareasofcompetency, we can analyze how individuals functionalong each of the three developmental continuum, bothatanygivenmomentandovertime.Withthesetools,wecan chart long-term growth and progress as well as os-cillationor regressionindependently in the understand-ing,management,andpersonalmeaningofrisks,inthiscase to health, and social relationships.

To bring this abstract and theoretical discussiondown to earth, we return to Gunnars and Bjorns re-sponses to questions about drinking in the Risky Busi-ness Interview. First, we locate where their responses,as we interpret them, fall on the developmental contin-

53

RISK AND RELATIONSHIP IN ADOLESCENTS

2Our model can examine any domain of risky activity in the con-

textofthequalityofanyofanindividualsspecificinterpersonalrela-tionships. In our analysis of the responses given by Gunnar andBjorn,we focused on their relationships with their parents andpeers,the relationships of greatest significance to each of them. The list ofmeaningful social relationships to connect to risks is not limited,however, to just these two categories. It could easily expand to in-clude grandparents, siblings, other kin, teachers, coaches, mentors,andothers. Which socialrelationships we study dependon which areimportant to the individual in the context of the risks in question.

Table 2. The Relationship Interview: Parents

Topics Focal Issues Key Questions

General description of interpersonalrelationships with parents.

Closeness How would you describe how you get along with your parents? Inwhat ways do you feel close to your parents (father, mother)?

Conflict Resolution What kinds of conflict do you have with your parents? How are yourvalues similar or different? To what extent do you feel a sense ofautonomy in your relationship to your parents?

Specific Risk-related Incidents/Actualreal life situations with parents Drinking How did your parents react when they learned you drink? What conflictcomes up between you and your parents around matters of drinking?How do you resolve these conflicts?

Table 3. The Relationship Interview: Peers and Close Friends

Topics Focal Issues Key Questions

General description of interpersonalrelationships with peers and close friends

Closeness In what ways do you feel close to your friends? Why are yourclose friends important to you?

Conflict Resolution What kinds of conflict do you have with your friends? Whousually decides what to do when you cannot agree?

Specific risk-related incidents/Actual reallife situations with peer and close friends

Drinking What kinds of things do you and your friends do when you aredrinking?Whyisdrinkingimportanttoyouandyourfriends?

-

8/4/2019 3179972

8/20

uum for each of the three areas of our psychosocialframework. Then we examine the connection betweentheir perspectives on the risk of drinking and the matu-rity of the ways they reflect on their relationships withothers.

Applying Our Psychosocial

Development Framework to the Risky

Business of Drinking

Understandings of the Risks of

Drinking

The first set of questions we asked Gunnar andBjorn focused on their knowledge of alcohol use intheir own world. We wanted to understand the psy-chological theories each holds about why adolescentsand adults in general (not only their own friends andparents) do or do not drink. We were also interested intheir knowledge of Icelands national health policiestoward alcohol and their sociological theories aboutwhy these policies exist. For example, Gunnar knewthe government does not permit advertising about al-cohol on television. When we asked him what hethought was the basis for this policy, he replied, Sothat more alcohol wont be sold. So people wont drinkso much. Bjorn also knew that television advertise-ments for alcoholic products are forbidden by law inIceland, but his explanation for why these laws hadbeen passed was In order not to encourage youngstersto drink alcohol. Its soeasy to influence them, they areso unmolded somehow. They cando themselves seri-ous harm; they dont reallyknow what they aredoing.

Individuals derive factual knowledgeabout the risksof drinking from several sources. One kind of knowl-edge is derived from the physical and biological sci-ences (e.g., that the percentage of alcohol by volumevaries in different kinds of alcoholic beverages, for ex-ample,orhowalcoholaffectsthebrainandotherorgansofthehumanbody).Asecondkindmightbetermedso-

cial knowledge (e.g., that by law, advertisements thatpromote sale of alcoholicbeverages arenot allowed ontelevision,innewsarticles,ormagazinesinIceland;thataddiction most often has detrimental effects on familyrelationships). An individuals developmental under-standing of risks to health in our framework, however,means the level of perspective coordinationan individ-ualusestointerpretknownfactsabouttheriskunderex-amination in connection to his or her understanding ofthe natureand pattern of social relationships. This kindofunderstanding,ofnecessity,occursthroughthecoor-dinationofsocialperspectives,betheybetweenselfandother,selfandthepeergroup(orfamily), orbetweenself

and society (see Selman, 1980).Gunnar and Bjorn have the same factual knowledgeabout Icelandicnational policies toward alcoholic bev-erages. They both knew the government does not per-mit companies to advertise alcohol on television. Yet,we find important developmental differences in theircapacity to integrate these facts into their social per-spectives, that is, to coordinate the relevant andsignifi-cant social points of view. Gunnar seemed to see thelaw as a blanket rule. To him, the law represented an at-tempt by them, meaning the government, to manageor control peoples behavior. He seemed to interpretthe governments point of view as single-minded, uni-

lateral, and aimed solely at controlling people.Bjorn, on the other hand, acknowledged that differ-

ent people have different perspectives, and focused onthe coordination of perspectives between society andthe individual. He seemed to be able to put himself inthe role of what George Herbert Mead (1934) calledthe generalized other. From that position, heempathetically realized that societys youngsters donot have the facts or the understanding (perspective)necessary to protect themselves against the powerfulforces and influences of commercial advertisements.Because young children, or their parentsguardians,may not be able to do it themselves, society must blockadvertisements for alcohol from reaching the minds ofunmolded youth. Said differently, Bjorn was awarethat younger children, whose media literacy is limited,need protection.

From our perspective, compared to Gunnar, Bjornexpressed a more differentiated point of view. Hebetter expressed, and probably better understands, thesocial concerns behind governmental health policies.Wedo not ruleout the possibility that Gunnar may wellunderstand how vulnerable young children are to thelure of advertising. The bar of understanding over

54

SELMAN AND ADALBJARNARDOTTIR

Figure 1. A psychosocial view of risk (e.g., alcoholic drinking)

and relationship (e.g., friendship, parentadolescent) competen-

cies within a developmental framework.

-

8/4/2019 3179972

9/20

which he is able to vault may be higher than we think.Even if so, he certainly did not choose to reveal this un-derstanding in his discussion with us.

Strategies for Managing Drinking in

Social Contexts

Our construct of interpersonal strategies to managerisks has the same underlying developmental structureas our construct of the understanding of risk. To ana-lyze strategies to managetherisks of drinking we inter-pret the actual strategies expressed (or observed) inrelation to how the individual coordinates perspectiveswith others in the use of a particular strategy at a partic-ular time. The evolving forms these strategies take,viewed developmentally, range from impulsive andunilateral at lower levels to higher level strategiesoriented toward reciprocity, compromise, and collabo-ration (see Adalbjarnardottir & Selman, 1989; Selman& Schultz, 1990). Indeed, in our risk and relationship

framework, the strategies individuals use to managetheir own health risks are, in essence, interpersonalstrategies.

To assess their repertoire of strategies, we askedGunnar and Bjorn impersonal questions about twohypothetical social drinking dilemmas: one involvingparents, the other involving peers. Both of these sce-narios centered on individuals their own age who (asthey themselves sometimes do) were dealing with adifficult interpersonal situation that involved decisionsabout drinking. For our focus on the risk of drinking inthe context of a peer relationship, we presented the fol-lowing dilemma:

Jon is a boy about your age and is against drink-ing. His best friend, Dori, knows about a partywheretheycanbringsomebrewanddrinkwithfriends. Dori says he is going to the party andplans to drink and urges Jon to join him. WhenJon hesitates, Dori teases him, saying that Jon ischicken, and pressures him to come along.

We then asked questions structured to focus, in se-quence, on how Gunnar and Bjorn construct the natureof the problem, the range of strategies to resolve it,what the best solution might be, and possible out-comes. For example, we asked both Gunnar and Bjorn,What do you think is the best way Jon can deal withDori in this situation? Gunnars response was Justtell Dori to go out and have a good time with the otherkids. Bjorn said, Jon should try to explain to Dorithat he has a right to his own opinion, and that friendsshouldnt force each other to do things. Jon could sayhe will go along but stick to his own decision not todrink.

When we asked Gunnar what he would do if hewere Jon, he said, Id go with Dori and get drunk.

When probed, he responded somewhat defensively,Just because its a lot of fun. When we asked himwhy getting drunk is fun, he brightened a bit, saying,Its so much fun to be high, [you] feel good and thatfascinates me. When we put these questions to Bjorn,he said, Id probably go along with Dori, I am not thatmuch against drinking alcohol, even though Im not

exactly in favor of it. I would try to convince him thatwhen you drink liquor its not just to get drunk.Our developmental analysis classifies the form of

the interpersonal strategy each adolescent suggests.The form of Gunnars suggestion to solve Jons drink-ing in the context of a peer relationship di-lemmaJust tell Dori to go out and have a goodtimeis predominantly unilateral. When Gunnarsays just tell, we take him to mean that he believesthat to resolve this conflict, one individual (here it isJon) simply tells, in a non-negotiable way, the other(Dori) what to do. According to Gunnar, the othershould just listenand, presumably, obey. Regardless

of the level of perspective coordination of which he iscapable, in Gunnars mind when it comes to resolvingthis conflict he entertains only one perspective. Saidanother way, even if he can coordinate multiple per-spectives, Gunnar attends to the will of only one indi-vidual at a time in this particular context ofinterpersonal negotiation.

Bjorn, on the other hand, suggests a compromisestrategy that involves respect for the perspectives ofboth participants in the negotiation. He says, Jonshould try to explain to Dori that he has the right to hisown opinion, and that friends shouldnt force eachother to do things. The difference between Gunnars

use of the word tell (reflecting a unilateral orienta-tion to relationships) and Bjorns use of the word ex-plain (indicating, at minimum, a reciprocalorientation) is crucial to the validity of our analysis.

Awareness of the Personal Meaning(s)

of Drinking

To understand an adolescents behavior in a givendomain of risk we need to know about more than his orher understanding of its pitfalls, or the repertoire ofskills he or she has to deal with it. We need to knowwhat taking a risk, at a particular time and place, meansto that individual in relation to his or her personallifehis or her passions, aspirations, frustrations, andanxieties. Personal meaning is sensitive to both theparticular context (place) and to the effects of past per-sonal experiences (time).

We classify the level of awareness of personalmeaning of any risk considered taken based on thedepth of perspective the individual is able to hold atthe time of the interview. The least differentiatedlevel is an orientation that dismisses, or does not see,the personal meaning of the risk to the self. The most

55

RISK AND RELATIONSHIP IN ADOLESCENTS

-

8/4/2019 3179972

10/20

insightful level is an orientation that connects themeaning of the risky action to how it effects the qual-ity of the relationship of the self to others. It is likelythat individuals operatesay, mean, and dothingsin ways that are interpretable simultaneouslyat several levels of personal meaning. Nevertheless,we limit our developmental interpretation of their in-

terview responses to the prodominant level of per-sonal meaning we believe underlies the particularstatement (see Levitt & Selman, 1996; Selman et al.,1997). A developmental analysis of the personalmeaning of any risky action requires us to interpretthe level of perspective coordination we believe theactor is taking to heart in the specific comments ex-pressed at that particular moment.

To assess the personal meaning Bjorn and Gunnarand other adolescents make of their own patterns ofdrinkingweaskedquestionsdesignedto elicittheir per-spectives on their past, present, and future behavior.Whydidtheystarttodrink?Whatdoesdrinkingmeanto

them now? What place do they think drinking will havein their lives in the future? Table 4 shows how somesample answers to these questions fit into our develop-mental frameworkand illustrates, by implication,how an individuals capacity to take different perspec-tives might evolve as he or she matures.

In response to our past-oriented question, why hepersonally started drinking several years ago, Gunnarsaid, I started just for fun, like everybody else. Fun tobe at parties. Its fun being drunk, you know, down-town. With reference to Table 4, we interpret Gun-nars response as being primarily rule-based andimpersonal. He seems to suggest a blanket rule that

applies to the motivation of all individuals who act ashe does. We take him to mean that he believes his owninitiation into drinking was, and is, no different from

that of anyone else who drinks. He seems to suggest animpersonal rulethat drinking is fun for everyonewho tries itto guide a very personal decision.

When we asked Bjorn to think back on why he firstbegan to drink alcohol, he said,

Because I thought it was exciting. I just wanted

to try it and feel what being high was like. IwantedtotrynotbeinglikeIam.Ihavebeenmy-self for 15 years, and I wanted to try somethingthat would change, like, my personality.

Bjorn takes a personalized and self-reflective per-spective on his own past actions. He sees his own indi-viduality as a cause of his actions and differentiates hisown personal needs from those of others. His com-ments seem based on an awareness of his own personalconfiguration of psychological needs. Accordingly, wecode the personal meaning of his response at aneed-based and self-reflective level.

WhenweaskedGunnar,Inwhatwayareyoudiffer-entnow from peoplewhodont drink? Gunnar repliedwith a careless smile, Umm, humm. I drink and theydont. Is that the only difference? the interviewerasked. Impatiently, Gunnarsaid, No, they enjoy them-selves less. We interpret this comment as a relativelyimpersonal blanket (that is, rule-based andundifferen-tiated) statement, perhaps even a bitdismissive in toneand substance toward nondrinkers or even toward peo-ple who drink in moderation. According to Gunnarsrule-based and undifferentiated level of expressedself-awareness, all drinkers, of which he is one, enjoythemselves,andallnondrinkersarelumpedtogetherasa

classofpeoplewhoarereallymissingoutonsomething.Bjorn thought for a moment before answering the

same initial question, and then replied in this way: I

56

SELMAN AND ADALBJARNARDOTTIR

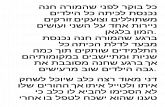

Table 4. A DevelopmentAnalysis of thePersonal Meaningof Drinking.Examples of Five Developmental Levels ofAwareness forEach of Three Selected Issues (Experimenting, Continuing, Stopping in the Future)

Developmental Analysis of

Awareness Dimensions

Past Reasons for Drinking

(Experimenting) I started

drinking because

Present Attitude Toward

Drinking (Continuing)

I drink because

Future Orientation Toward

Drinking (e.g., When to Stop

Drinking) I will stop

Dismissive Level (of Awareness) Everyone drinks. Just for the hell of it. When I am fed up with it.

Rule-Based: Impersonal Level Makes kids feel cool. Its a habit. If everybody stopped.

Rule-Based: Personal Level I had to, in order to fit in. It makes me feel loose. If I cant handle it.

Need-Based: Self-Reflective Level I felt I was more grown-upbecause I could handlemy liquor.

It helps me communicatearound sensitive issueswith my friends if I amless inhibited.

If I felt I wasnt strong enough tomanage it well.

Need-Based: Contextual Level It was a part of my culture.My friends and familylike to drink when theyare together.

As long as it does not takeover me. It is part of mysoial life that brings us(friends) together.

If I felt I wasnt strong enough tomanage it well. But, its hard tostop because it is all around. It isnot simply an automatic choice.Its part of the fabric of oursociety.

-

8/4/2019 3179972

11/20

might be more curious; just more daring. And maybe Ihaveadifferentfamilysituation.But,Imean,allsortsofpeople drink and all sorts of people dont drink. I dontthink theres a lot of difference. To us it seems thatBjorn does notsimplydisagree with Gunnars perspec-tive,healsodisplaysdeeperself-awareness.Hedoesnotbelieve a general differenceexists between adolescents

whodrinkandthosewhodonotbasedonthatfactalone.Instead of making impersonal blanket or rule basedstatements, he identifies what differences there are be-tween him and other peoplebased ona range of person-ally connected factors of which he is aware. Theseinclude individual differences in the needs of differentpersonalities (I might be more curious more dar-ing) andin thepatternsof ones interpersonal relation-ships (I have a different family situation).

ForaglimpseofhowBjornandGunnarlookintothefuturewe refer back to the longerstatements we quotedatthebeginningofthisarticle.ForGunnar,tosayhisdadcouldstopdrinkinganytimedoesnotseemtotakethe

perspective of someone who seems only to be able tostop drinking on the threat of death. Bjorn, on the otherhand,differentiatestheeaseofdecisionsmadecurrentlywith those decisions in a future time under conditionswhen the self is in an addictive state.

Most social scientists would agree that both Gunnarand Bjorn are at risk for having problems with drink-ing because each has a history of alcoholism in thefamily. In our view, however, Bjorn seems to exhibit alevel of self-awareness and social perspectivein-cluding the awareness that he and others change overtimethat could help himin the futurebetterdeal withthe risk factor they share. In this sense, he appears to us

to be psychologically more resilient than Gunnar. Ourhunch is that on average, adolescents whose patterns ofpsychosocial development resemble Bjorns will bebetter able to learn how to drink well without caus-ing severe or permanent damage to themselves, thanthose whose patterns are like Gunnars.

Comparing Gunnars and Bjorns

Perspectives on the Risks of Drinking

To us, the evidence suggests that across each of thethree areas of psychosocial competence, Bjorn is ableto express a greater capacity for coordination of per-spective than is Gunnar. He responds, on average, at ahigher level, and his observations are more consis-tentlyhigh levelacross psychosocialareas. In partic-ular, the Risky Business Interview provides us withevidence that Bjorn has a more differentiated aware-ness of what meaning drinking has for himself person-ally than does Gunnar. Bjorn generally articulates aneed-based and self-reflective level of expression(see Table 4). Gunnar has not provided us with muchevidence that he is capable of this level of understand-ing of himself and of others. Of course, under different

conditions he may be able to express what we wouldconsider a more mature perspective. Certainly the evi-dence (if true) that he has not yet developed a more ma-ture understanding does not mean he will not in thefuture. Nevertheless, by our standards, across the ter-rain of our entire interview with him, statement bystatement, his conversation has a predominantly

rule-based flavor to it, sometimes impersonal, some-times personal.

Two Theoretical Concerns

At this point in our discussion, we need to addresstwobasic andrelated concerns that challenge thevalid-ityof theconnection between actual risk-taking behav-ior and psychosocial development. The first concern isthis: How can we be sure each of these boys does whathe says? Did Bjorn act within his social world (e.g., hisactual drinking behavior) in accordance with his rela-tively enlightened expressions of self-awareness, or

did he just talk a good game with us? Conversely, howcan we be so sure that Gunnar was as dismissive orrule-based in his deeds as he was in his words? Did heact as unilaterally as he said he did, or might his com-ments reflect some kind of noncompliant reaction tothe interview or the interviewer?

Second, how can we be sure each boy is able to saywhat he really means? Did Gunnar mean to sound sodismissive andunreflective, or might he lack thewordsto express a more mature level of self-awareness?Con-versely, did Bjorns comments really emerge from awell-differentiated awareness of his personal needsandsocial relationships, or arewe givinghimtoomuch

interpretive credit, reading too deep a level ofself-awareness into his language? How valid are ourpsychosocial interpretations of Bjorn and Gunnars re-sponses to our interview questions?

In the absence of observational evidence, to increaseour confidence in the credibility and dependability ofour developmental interpretations of Bjorn and Gun-nars perspectives on risk, we need to expand our scope.We need to include information about the anatomy oftheir view of their close relationships. Beyond this,however, we aimed to demonstrate the developmentallinkages betweenmaturity of perspectives on risk to ma-turity of perspectives on relationships.

Perspectives on the Quality

of Close Relationships

What additional evidence do we need to support ourmethods to assess teenagers levels of psychosocialmaturity? Our Relationship Interview can deepen andenrich our analysis in at least two ways. First, it en-courages each boy to discuss how he relates to individ-uals important to him. Second, it allows each to

57

RISK AND RELATIONSHIP IN ADOLESCENTS

-

8/4/2019 3179972

12/20

express his personal point of view toward his owndrinking patterns in thebroader context of his own per-sonal social relationships. Just as risks and relation-ships mingle within the psychosocial anatomy of eachboys mind, material from our two interview protocolsflows together, each providing needed illuminationand clarification of the other.

To summarize our analysis of the data from the Re-lationship Interview we begin with a brief descriptionof how each boy reports his family dynamics; howeach views the quality of his relationships with hismother and his father. We pay particular attention tonegotiation of closeness (intimacy) and themes of con-flict (autonomy). We then draw excerpts from their in-terviews to summarize the way each boy depicts hisparents view toward his own use of alcohol and whatkinds of ongoing negotiationscommunications he andhis family engage in around matters of drinking. Werepeat this process with Bjorns and Gunnars descrip-tions of their peer relationships, focusing in particular

on each boys relationship with a friendhe considers tobe among his closest.

What Gunnar Says About His

Relationships With Parents and Peers

How close is Gunnar to his parents? At 15, Gunnarlives with his parents and his younger brother. His fa-ther, a fisherman, and his mother, who works in a gov-ernment agency, are in the process of separating. Witha slight edge to his voice, Gunnar describes his fatheras being so shut off but says that his mother cares a

lot about me and all that. Although he reports that hespends very little time with his mother, he claims hefeels closer to her than to his father. Yet he also claimsto confide little in either parent, neither sharing hisconcerns with them nor being interested in hearingtheir problems with anysympathy or understanding: Ijust, really, can hardly be bothered to listen to it, hesays, referring to my mothers personal problems.

How does Gunnar say he manages conflicts with hisparents? Gunnar enumerates three primary subjects ofconflict with his parents: his attendance at dinner, hisschoolwork, andhisdrinking. At first he claimsthat hisparentsknowthathedrinksbutnothowmuchhedrinks.Then he contradicts himself, saying, Sometimes theyknow, sometimes they dont. Like now, they alwayscheck in the morning. They always know about it. Idont care. When asked why he doesnt care, he re-spondsquickly,Idontknow.Thenheadds,MaybeIdrink often, but I never get very drunk; I get drunk, ofcourse, but not really dead drunk very often.

How does Gunnar connect his relationship to hisparents to his drinking behavior? Gunnar says hismother drinks moderately, and his father is an alco-holic who now doesnot drink atall. He claimshe is not

concerned that his parents know about his drinking,only that he suffers from their knowing financially,that is, they dont give him his weekly allowance ifthey think he has been drinking. He snarls that whenhis parents first found out that he drank they made allsorts of threats I wouldnt be allowed out, and craplike that, on weekends. And then they saw it didnt

work. Then, becoming contrite, he says, Because Icare about my parents, I am willing to give it a breakfor a while, if they get angry, so they will not botherme. On the other hand, Gunnar also acknowledgesthat his parents concerns have some legitimacy; theyarise, he concedes, out of a family history of alcohol-ism and a concern for his health.

In what ways is Gunnar close to his peers? Gunnarentwines his drinking inextricably with his friendshipsand peer relationships. He tells us he drinks almost ex-clusively with his male friends. He reports to have hisbest times with friends when he is drinking on week-ends.Contrary to his feelings about sharing any of his

problems with his parents, Gunnar tells us he feelsclosest to his best friend when they have family prob-lems to discuss with each other. Not surprisingly, alco-hol seems always to play a major role in this intimateactivity: He [Gunnars friend] was really blind drunkontheLaborDaylongweekend.Hisdadisdeadandhewas telling me about it, and all that. Telling me abouthisemotions andall that crap.When we asked Gunnarwhat he likes about this friend, he said, He just helpsme sometimes, if I get into trouble or something [like afight]. He would do anything for me and I would doanything for him. He admits there are things or emo-tions, he avoids talking about with his friends, but he

does not say what they are. A discussion of the degreeto which Gunnar and his friends spend time drinkingtogether dominated our interview with him.

How does Gunnar say he deals with conflicts withfriends? Material here is sparse but very telling. Gun-nar reports that he andhis friends have conflictsaroundminor matters, usually choices of movies to attend, orways to go to a party and the like. He emphasizes thatwhenever disagreements arise with his close friends heseems to be the one to defer. If the other person reallycares so much, Gunnar grumbles, then he is the onewho is always willing to go along.

How does Gunnar connect his relationship with hispeers to his drinking behavior? Gunnar makes verystrong connections between his social life and drink-ing. Drinking has become a habit, Gunnar admits.Its more fun to dance when high, and its a way to fitin. He does see the problems to which drinking canlead. All the tough guysby which he means theguys a little bit older than he isare messed up be-cause they do drugs, something which he claims toavoid. However, drinking on the weekend plays a ma-jor part in Gunnars life. Going out and having funmeans to drink heavily, to get drunk, but not blind

58

SELMAN AND ADALBJARNARDOTTIR

-

8/4/2019 3179972

13/20

full. When he gets dead drunk, he claims, hisfriends are there for him to rely on.

Although Gunnar minimizes conflicts with friendsby accommodating somewhat passively, he notesthere is quite a bit of conflict between his friends andother groups of boys his age. These intergroup con-flicts often become physical and violent, and Gunnar

acknowledges that they often occur at parties wherealcohol is easily available or on the city streets afteran episode of drinking. Passive within his own group,as a part of that group Gunnar is aggressive.Friends, Gunnar says, are there to help one an-other when they get into a difficult situation with oth-ers, like when we go downtown. We dont like to bepushed around. Gunnar also admits to some inci-dents of vandalism. However, he seems to suggestthat being under the influence of alcohol at leastpartly relieves him of responsibility for the trouble hecauses others or the damage he does to propertyor,more typically, he defensively blames others.

Not all of Gunnars reflections on his drinking ex-periences are positive. Once mugged when drunk, headmits he does not like to get into the habit of drinkingjust for drinkings sake: In the winter when it is toocold outside to hang arounddowntown, its nothing butcrap. He reports becoming quite scared when at onepoint he mixed too many types of drinks and ended upgetting alcohol poisoning. Looking toward the fu-ture, Gunnar claims he could stop drinking just likethat, if I want to, just like my father did. Nevertheless,he adds, wistfully, You cant stop drinking over thesummer, its so much fun.

Perhaps the most salient theme that emerged from

our conversations with Gunnar was how drinking hadseeped into every important aspect of his social life. Itdefines what he and his parents fight about and it facili-tates his closeness with peers; it is there when he is introuble and when he parties.

What Bjorn Says About His

Relationships With Parents and Peers

How close is Bjorn to his parents? Bjorns parentsseparated several years ago, but still relate to one an-other. He lives with his mother but claims to have agood relationship with his father. He stays overnightonce a week at his fathers place and reports that his fa-ther comes often to hismothers house fordinner. Bothparents are graduates of the national university, andboth of them work in small businesses.

Bjorn says he is very close to his mother. We talkabout everything, he reports, and laugh a lot to-gether. He goes on to say, Its a very good talking re-lationship and were almost always friends. Hewillingly tells her about the girls he has crushes on andreceives some reciprocal revelations on his mothers

part. Unlike Gunnar, Bjorn reports a high degree of in-terest in his mothers personal problems. He says he isable to connect with his father by doing things to-gether, but reports that his father has a great deal ofdifficulty talking about emotions and [is] sort of shutin himself.

How does Bjorn say he manages conflicts with his

parents? Bjorn reports he has no chronic disagree-ments over major issues with either of his parents butdoes acknowledge irritable flare-ups. It does happenifit reallygets onmy nervesand Im a bit tense aswell,[if] Im doing something important, too, then I mightsay, Cut it out, will you, but it happens very seldom.How do Bjorn and his parents resolve conflicts? Ac-cording to Bjorn, We talk things out, as we have avery democratic relationship.

How does Bjorn connect his relationship to his par-ents with his drinking behavior? Bjorn reports that hismother is a moderate drinker. His father, an alcoholic,hasbeen sober forseveral years. Bjorn is sure his father

will not take a tumble because he is strong-willedand theres nothing positive about alcoholics whodrink, of course. Bjorns parents know that he drinks,andhefindsitimportantthattheyknow:Idontwanttodo things behind my parents back. If they were to findoutaboutitsometimelaterthatIhadbeenlyingtothem,then, of course, if we cant trust each other then no onewill trust me. Bjorn describes his mothers attitude to-ward his drinking as being somewhat ambivalent: Shethinks its just really quite normal that youngstersstarttryingthingsoutShesnotterriblygladaboutit.Ohh, she thinks Its a bit early, see? She thinks Ishouldwait until I have started grammar school. Bjorn

assumes his father does not disapprove, or even that heendorseshissonsdrinking,buttoustheevidence(Af-terall,hedidgetmeabottleonIcelandicNationalDay)seems a bit flimsy.

In what ways is Bjorn close to his peers? Bjorn sayshe holds two or three close friends in high esteem: Wealways play together and go out for a game of soccerand the like. Although other peers confide in him,Bjorn says, he himself talks about his own personalproblems andworries only with his twoclosest friends:Its mainly when were talking about something like,some personal matter girls or something like that.

How does Bjorn deal with conflicts with friends? Itis interesting that, like Gunnar, Bjorn often feels he istoo submissive in his peer relationships. This happenswith one of his friends in particular:

Heoftentries,like,tohavehiswayandIfeelitsoften a bit humiliating for me. If I finally well,he says to me, Do it, do it, do it! without end,and then, if I say yes, I always feel like hes forc-ing me and he always finds a way to get me togive in.

59

RISK AND RELATIONSHIP IN ADOLESCENTS

-

8/4/2019 3179972

14/20

In the case of this friend, whom he experiences asvery pushy, Bjorn is often displeased with himself fornot standing up for what he wants to do; at the sametime, however, he explains this friends actions as be-ing a sign of insecurity. Finally, Bjorn reports that ingeneral he challenges his close friends when they dis-agree over decisions like what to do or where to go

and that his goal is to achieve a balance as to whogets to choose. How does Bjorn connect his relationship to his

peers with his drinking behavior? Bjorn does not linkhis drinking behavior with his friendships to the samedegree Gunnar does; drinking does not seem to domi-nate either his shared experiences with friends or hisconflicts with them. Two important themes, however,do emerge from our conversation with Bjorn aboutwhat drinking means to him in the broader context ofhis social life. First, Bjorn says he values drinking be-cause it enhances his social skillsby which he meansin particular that it helps him manage his strong feel-

ings of interpersonal attraction to girls. Drinking helpshim overcome what he feels is his natural shyness:

For instance, if you were really stuck on somegirl, eh Youremaybe talking to hernormally,like then when youre drunk and see her, you cancome up with Oh, Ive always been in love withyou and the like. And if it looks like maybe its just nothing but drunken blabbering, just thesame, you know, shell remember it but shewont feel stupid. Youre not stupid even if yousaysomething like that, because youwere drunk.But it has an effect all the same, you know.

Second, like Gunnar, Bjorn speaks of the costs anddangers of drinking to him personally, but from a dif-ferent perspective. Clearly, to him the worst of these isthe humiliation he would feel if he were to lose hisself-control while under the influence. He says,

More than anything, I dont want to make a foolofmyselfagainlikethetimeIgotsickatafamilyparty and was carried out feeling enormouslyembarrassedandashamedofmyself.Idontwantto lose memory and do things I would really re-

gret. You know, I dont want to wake up insome alley with my pants down around my an-kles and a used condom beside me.

Adamant in his belief that becoming a man means be-ing able to manage ones alcohol, Bjorn has no desireto abstain, but he wants to be able to control hisdrinking. In the same breath, he confesses he does notwant to get addicted and confidently predicts he willfollow in the footsteps of his mother rather than thoseof his father.

Comparing Gunnars and Bjorns

Perspectives on Relationships With

Peers and Parents

Gunnar and Bjorn are the same age, attend the sameschool, and come from families of roughly the sameeconomic status. However, their parents differ in edu-

cational level. Both parent couples have struggled withtheir marital relationships and are either separating ordivorced. Both Gunnars father and Bjorns fatherhave a history of struggling, apparently with some de-layed success, with alcoholism. Both Gunnar andBjorn are the eldest children in the family and both areregular drinkers. Here, within a developmental analy-sis, the more obvious similarities end.

Bjorn claims he shares his feelings about personalmatters with his mother in a mutual way. He says it iscrucial his parents trust him to be open and honestabout his drinking, so they will trust each other in gen-eral. Gunnar does not express any interest in doing so;

in fact, he scornfully rejects the closeness his motheroffers. He does not really want to inform his parentsabout his drinking, but says he is willing to do so,partly out of some consideration of their concerns. Pri-marily he does it to avoid their anger and to get his al-lowance. Gunnar tells us he deals with conflicts in hisfamily around his drinking in unilateral ways or theyare not discussed at all.

Drinking for Bjorn means improved relations withgirls and the challenge of maintaining someself-control. Bjorn claims to discriminate among hispeers, and says he finds it very valuable to share per-sonal matters with those friends whom he trusts the

most. When conflicts arise between them, he believesit is important to find some balance of power, althoughhe reports that he is not always successful in doing so.He feels uneasy about unequal decision making andstrives to attain some kind of reciprocity. Gunnar alsodislikes feeling he is always the one to accommodate,but he does not seem to make much effort to find abetter balance with his friends. Drinking, for Gunnar,means connection with his close male friends, whoprovide him with protection when he becomes unin-hibited and subsequently aggressive.

From our developmental perspective, we interpretBjorns responses to suggest that he has discoveredand begun to consolidate a third-person perspective onrelationships between himself and his closest friends.He also appears to be working hard to achieve a senseof mutuality in his relationships with his parents. Gun-nar on the other hand, is still struggling to secure a re-ciprocal foothold with his friends, but at this point, heseems to have no easy way to move beyond a unilat-eraland seemingly difficultrelationship with hisparents. From a developmental point of view, Bjornseems to be able to achieve greater perspectivethatis, he has a greater capacity to understand and coordi-

60

SELMAN AND ADALBJARNARDOTTIR

-

8/4/2019 3179972

15/20

nate multiple perspectiveson both risks and relation-ships than Gunnar is capable of doing.

Risk and Relationships:

Parallel Tracks

Anydevelopmental analysis must locatean individ-

uals words and actions within a broader cultural con-text (Edelstein, 1983; Rogoff & Chavajay, 1995) toenrich their meaning. Looking at cultural factors thatmight affect our interpretation of the differences in un-derstanding, management, and personal meaning ofdrinking that we hear expressed by Bjorn and Gunnar,extends our understanding of the connections betweenalcohol, risk-taking, and relationships.

Contexts, Culture, and Connections

Forcenturies, Icelandicculture hasinfused in itsboysthe belief that the ability todrinkwell is a valued com-

ponent of adulthood. In Egils Saga (1986), written inIcelands own language in the 13th century, the10th-centuryhero, Egill Skalla-Grimsson, is given alco-hol (mjur), at the ageof three, by a slave at a farmersparty. While under its influence the child produces apoem of such skill and accomplishment about this eventthat it has been recognized and admired in Iceland eversincethat is, since the 10th century. Sagas like Egils,that recount the drinking exploits of adventurous heroeshave helped develop the Icelandic identity, and are stillreadbyschoolchildrentodayaspartoftheireducation.ItwouldseemthatinIcelandicculturethebenefitsofdrink-ing well have been valued for a long time.

This recounting helps us understand one element ofthe importance of drinking to both Bjorn and Gunnar:Forculturalaswellaspersonalreasons,foreachofthemit is a part of the transition from boyhood to manhood.Actually, Bjornacknowledges this.Thedifferences be-tween the two teenagers lie in what function alcoholservesforeach. Gunnars behavior fits the troublesomepattern of high levels of heavy drinking and aggressivebehavior seen among teenage boys in Iceland today(Hibell et al., 1997). Does this mean that his cultureviewsthisbehaviorandthedamageitcausesasaninevi-table toll that adolescent boysand the rest of soci-etymust pay as they travel the road to adulthood?Certainly not! Today both Icelands policymakers andthe nations society as a whole rank excessive alcoholuseby adolescents, and itsconnection to other drug useand aggressive behavior, among its most serious soci-etal problems (e.g., Ministry of Justice, 1998).

Why, then, according to the epidemiological datacited earlier, are so many Icelandic youth not able todrink well? The findings of our study resonate with an-other echo from Icelands pastone that suggests anadditional link here between drinking and the qualityof personal relationships. In Njals Saga, also written

in the 13th century, the narrator tells us, Ber er hvera bak, nema sr brur eigi, which can be literallytranslated as Ones back is bare without a brother(Njals Saga, 1982, p. 338). What does this statement,also a popular saying in Iceland, mean? Differentthings to people at different developmental levels, wewould expect. Let us consider its possible personal

meanings to Gunnar and Bjorn in the context of alco-hol, risks, and peer relationships.At this point in his life, Gunnar seems to operate in

terms of the most literal, obvious meaning of the say-ing. He wants social ties but seems to expect to give orreceive littlemore than reciprocal self-protection in hisrelationships with peers. Bjorn seems to value a degreeof intimacy with peers both in and of itself and becauseit provides a chance for dialogue and mutual support.Whereas Gunnar appears to want to use alcohol to beable to cast off the ties of inhibition, Bjorn wants toloosen these bindings just enough to connect with oth-erswith girls, in particular, but also with close

friends with whom to share experiences. For bothboys, it is their capacity to make personal meaning thatmediates between their understanding of risks and thequality of their relationships with others.