Rupam_11

Transcript of Rupam_11

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

1/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

2/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

3/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

4/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

5/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

6/70

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in 2010 with funding from

University of Toronto

http://www.archive.org/details/rupamind11indi

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

7/70

RUPAMA JOURNAL OF ORIENTAL

ART

} m

n

\

mi7//>i^^>^

]CjfaLi%lni| luaiSLn

f^\^ . ^**fc

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

8/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

9/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

10/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

11/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

12/70

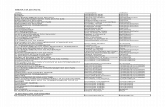

CONTENTS. Page*=-!. A Tibeto-Nepalese Image of Maitreya .. ... ... 7

II. Irdian Sculpture. By Eric Gill, O.S.D. (London) ... .. ... 7

III. Exhibition at the Government School of Art. By Agastya (Canopus) ... 7IV. Indian Art in Europe. By Dr. S. Kramrisch (Santi-niketan).. ... 8V. Indian Columns. By Dr. P. K. Acharya (Allahabad) ... ... 86

VI. A Visit toaSaint: "Chhari Shahmadar" ... ... ... 8VII. Notes on Raginis. By Kannoomal (Dholepur) ... ... ... 9

VIII. Exhibition of Indian Arts and Crafts ... ... ... ... 99

Reviews ... ... ... ... ... 101

Notes ... ... ... ... ... 107

All Rights of Translation and Reproduction are strictly reserved.

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

13/70

IA TIBETO-NEPALESE IMAGE OF MAITREYA.EVER since the early days of Mahayana,

the worship of Maitreya (Tibetan,byantM-pa ; Chinese, mi-lo-fo) theBuddhist Messiah has been a very popularcult. Indeed he is the recipient of homageequal to, if not more than, the Founderof Buddhism himself. li is believedthat Sakya-muni visited Maitreya inTushita heaven and appointed himas his successor, as the next Buddhato come to earth and to establishthe * dharma ' again in its purity after itwas forgotten by a degenerate world. Hisworship was at its height, in the days ofFa-Hian's visit to India. His image figuresamongst the earliest of the Gandhara sculp-tures, where he is depicted as an Indian princewith all the Bodhisattva ornaments, and canbe already differentiated by his symbol ofthe vase of nectar (amrita'kalasa) thoughhis other symbol of the naga pushpa is yetwanting. In the earlier type he is generallyrepresented as standing with the vase in theleft hand. The Chinese images are general-ly standing ones, though there are examplesin some of the Chinese caves which are

seated in the European fashion. The Mongo-lian specimens represent the image asseated with the legs closely locked (padma-sana) and are probably derived from theNepalese and the Tibetan models.

As an example of the Nepalese tj^je, thecopper gilt figure of Maitreya reproduced inthe frontispiece is of singular interest. Itbelongs to the most elaborately ornamentedtype of copper scidpture of seventeenth andeighteenth century Nepal, and approximatesto the style of the best specimens of Tarawell laiown to collectors of Nepalese Art.Besides the ordinary symbols of the vase andthe champa flower, we have an additionalattribute of the skin of the antelope. Theurna on the forehead is in oblong form. Thetwo hands are in the attitude of the vitarka(argument) and i;ara (charity). Possiblythis was the attitude in which Maitreyataught the Arhats in Tushita heaven. Theelaborate ornaments richly set with jewelswhich even figure on the decoration of the

border of the dhoti are very well knownfeatures of a period of the Nepalese school.But the necklace and the baj us on the upperarms offer here two very unique designs.The latter bears an intricate design of hansa-mithuna, a pair of swans interlocked at thenecks which are well known in earlierBuddhist ornamnents. In the necklace wehave a pair of peacocks which are introducedwith lot of life and charm. The tiara withfive jewels are carved with conventionalornaments specialised in Nepal. But theeffect of the elaborate decorations unhappilytends to overshadow the rhythmic andpassionate gesture of the trunk. There is avery significant movement emanating almostfrom the navel, which inclines for a time to-wards the left and graduaJly recover^ iispoise, coming to a halt, as it were, at theneck, where the head slightly mcved to theright, slowly descends on the shoulders inexquisite equilibrium. It is a variation ofwhat is technically known as the avangapose, and is a very characteristic and originsddevice of Nepalese sculptors. To very fineaesthetic qualities the example offers anotherinterest

inits inscriptions

on the lotuspedestal. The one claims it as a Nepsdeseproduct and the other claims it for TibetWe have attempted to meet both the claimsby characterizing the figure as a Tibeto-Nepalese specimen. We have more thanonce commented on the fact that out and outNepalese images are labelled and describedin many museums as Tibetam works, and thewhole relation of Tibetan to Nepalese Art hasbeen misunderstood or deliberately ignored.The Lamaistic School was the result of adirect pupilage 'to the Nepalese tutors;

and although it developed many spe-cial features the groundwork of theNepalese style was always a staple partof all Tibetan work. Evidences are nowpointing to the fact that many Nepaleseimages must have been made to order forthe use of Tibetan worshippers. The twoinscriptions on this image in the Newari andTibetan characters may well bear out oursuggestion. If the image was meant for

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

14/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

15/70

75

so Beauty is not to be confused with loveli-ness. Beauty is absolute, loveliness relative.The lovely is that which is or represents thelovable. The lovely is lovable relatively toour love of it Beauty is absolute and inde-pendent of our love. God is beautifulwhether we love him or do not; but the tasteof an apple is lovely only if we taste it andlove the taste. " Avalokitesvara " ^is beau-tiful with an absolute Beauty. A portraitof a lady is lovely because it portrays thatkind of woman who is lovable to those wholove that kind of woman and in that kind ofattitude, which is charming to those who arecharmed by it.

Beauty is therefore a thing of religioussignificance, ineffable, independent of fashionor custom, time or place, and not to be judgedby the material criteria of a commercial

civilization or by the threadbare culture ofan irresponsible governing class.

Now for the Sculpture of India we mayclaim at once that it is, genersdly and as op-posed to modern European sculpture, thework of men, who believed in the absolutevalue of Beauty. It is the work of men whoregarded Beauty not merely as a thing minis-tering to man's comfort and pleasure, butas a thing having a value utterly independ-ent of any pleasure it might give to men orof any power it might have of making hu-man life endurable.

It is not to be denied that works of artdo in fact give pleasure and do in fact makelife endurable, it is only to be denied that suchgiving is primarily the function of the artist.Nor is it to be denied that such worksas those of the Indian sculptors are pleasing.It is only because of their denial of the abso-lute value of Beauty that English people donot as a rule find pleasure in them. We havebecome so accustomed to regard the artistmerely as a purveyor of the lovable thepriest as a moral policeman the philosopheras a sort of " young man's guide to know-ledge "that we are incapable of viewingjustly the work of men who regard the artist,the priest and the philosopher as prophets ofGod.

Nor is it only the works of Eastern andof alien peoples that we view thus unjustly.We do the same injustice to the work of pre-renaissance and post-impressionist artists in

Europe. We are blind to the Beauty in thedrawings of children, we see nothing in thembut the quaint and ingenuous. We find novalue in anything unless we can weigh it hithe scales of human comfort. Thus we s&ythat an unhappy marriage is no marriageand that an unpleasant thought cannot betrue. Whereas, God is just as well as merci-ful and what God has joined cannot be putasunder.

So in this matter of Indian Sculpture wesay that because few men have more thamtwo arms, therefore an idol with ten arms isugly forgetting or not knowing that veri-similitude has no necessary connection witheither Beauty, Goodness or Truth. We saybecause, from the point of view of marrying,a woman with a figure like that of the Venusde Medici is more desirable, therefore the

wide-hipped, glove-breasted images of Patti-ni are necessarily ugly, bad and false. Wego to a game of football and bleune the play,,ers for infringing upon the rules of cricket.We apply the standard of a mechanical andgodless commercialism to wr.rks which areboth man-made and godly.

We can, however, claim the quality olinconsistency for we have not hitherto toany large extent denied the worth of any butimitative music, though the modern develop-ment of programme music may very likely

lead us to do so, and we do not as a rule insistthat all words shall be onomatopoetic.But how can we see that in which we do

not believe and what would be the good if wecould? The connoisseur's appreciation leadsnowhere but to an aesthetic snobbery, to theapotheosis of the dealer in works of art andto the filling of our museums. Such apprecia-tion does nothing to stem the tide of destruc-tion the destruction not merely of thingsof Beauty that is comparatively unimport-ant such appreciation does nothing to re-create in the people that attitude of mind inwhich alone Beauty is credible and to recreatein the life of the people those conditions underwhich alone the production of things ofBeauty is possible.

However, the appreciation or deprecationof Indian Sculpture or of any other sculptureor of any artistic productions is now a matterof very little importance, for any attemptto obtun either is in effect locking the stable

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

16/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

17/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

18/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

19/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

20/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

21/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

22/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

23/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

24/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

25/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

26/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

27/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

28/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

29/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

30/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

31/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

32/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

33/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

34/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

35/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

36/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

37/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

38/70

96

PATMANJARI RAGINI 5.44 & 45. This Ragini is describeid to be

an extremely emaciated female witheringaway in separation from her lover to such adegree that her life is despaired of. She has

on her neck a garland of withered flowersand she has abstained from food, drink, sleepand speech and is smarting under the pangsof separation. The dominant note of thisRagini is Pancham and is sung in thesecond part of the night in Spring.

RHETORICAL INTERPRETATION.The Nayaika (heroine) is a modest and

polite woman devoted to her husband who hasgone to a distant country on business. TheNayak (hero) is Dhirodatta and the pre-vailing sentiment is Vipralambha Sringarthe erotic sentiment which at its heightremains unsatisfied owing to the unavail-ability of the lover.

' IVDIPAKARAG.46. This Rag has sprung from the eye

of the sun and is seated on a mad elephant,radiating in the effulgence of his body, whichputs pomegranate flowers to shame. He isexceedingly handsome and wears a necklaceof matchless pearls and is surrounded bywomen. The Rag is sung in the Kharajnote in

Summer atnoon.

RHETORICAL INTERPRETATION.The Nayak (hero) is a crafty fellow

showing love to many women without beingtrue to anyone while his women are faithful,young, passionate and skilful in all the artsof pleasure. The prevailing sentiment isSambhog Sringar.

DESI RAGNI.47. This favourite Ragini of Dipaka-

Rag is of an extremely beautiful appearancewearing green garments and fine ornaments.She is lasciviously disposed and is seated ona couch by the side of her sleeping lover in arestless mood.

The dominant note of this Ragini isKharaj and is sung in Summer at noontime.

RHETORICAL INTERPRETATION.The Nayaika is a fully developed young

woman intent upon having her lover. Herlover is Dhirodhata. The prevailing senti-

ment is of mutual enjoyment with percep-tional feelings.

KAMODNI RAGINI 2.48 & 49. The Ragini is well dressed

in a fine yellow-coloured sari and a whitecorset. Her underwear is of red cloth andshe speaks sweet as a cuckoo (koel). She ilooking about in all the ten directions forthe arrived of her lover and sitting in theforest in a concentrated mood of mind.

This is sung in Dhaivatswar in Summerat noontime.

RHETORICAL INTERPRETATION.The Nayaika is a fully developed young

woman full of passion. Her lover is Dhiro-dhata. The prevailing sentiment is Vipra-lambha Sringar.

NATA RAGINI 3.50 & 51. She is dressed in a red sari

and decked out with all kinds of ornaments.She is clever, charming and radiant like gold.She is very careful of her secrets, and by hercharms, captivates the heart of her lover.She takes delight in acrobatic antics, and inthe course of indulging in such a gambol,her hand is resting on the neck of a horse.

The Kharaj swar is her dominant note

and her time of singing is the fourth part ofthe day in Summer.

RHETORICAL INTERPRETATION.The Nayaika is a young unmarried girl

full of passion and so skilful in the arts ofpleasures that her lover does not like toleave her even for a moment and is totallyenamoured of her. Her Nayak is Anukul,one who is most favourably disposed to-wards her. The prevailing sentiment isSambhog Sringar the feeling of love in thecourse of mutual enjoyment attended withsuch perceptions as seeing, touching, etc.

KEDAR RAGINI 4.52. This Ragini is shown to be guis-

ed like a female ascetic. A snake is castathwart her body for a holy thread, the infantmoon is worn on her head and the Gangesrests in the coil of her hair. This Ragini issung in Nesadhswar in Summer at noontime.

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

39/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

40/70

98

him. The Nayak is Dhirodhata and thesentiment is Vipralambha Sringar.

BASANT RAGINI 4.63 & 64. She is of a lovely, dark appear-

ance as the sweet smell comes out of her

lotus-like mouth and a swarm of black beesgather about her face and make a hummingsound. She has the beauty and lustre of theperson of Cupid and youth that captivatesyoung men. Her breasts are hard andshe holds buds of mangoe plants in her lotus-like hands.

This Ragini is sung in Kharaj swar inSpring in the second part of the day.

RHETORICAL INTERPRETATION.The Nayaika is a young passionate

woman who is well skilled in all the arts ofpleasure and who moves about in search ofher lover. Her lover is Dhirodhata. Thesentiment is Vipralambha Sringar.

ASAVARI RAGINI 5. (lUus. Fig. 1.)65 & 66. 'Her bewitching appearance

is that of a cloud and she is dressed in finewhite garment. She is sitting under a kadamtree entertwined with snakes in a coolwatery place.

This Ragin! is sung in Dhaivatswar inHemant or early cold season in the first halfpart of the day by experts in music.

RHETORICAL INTERPRETATION.The Nayaika is a bold public woman

moving about in white clothes on a full-moonnight in search of her lover. Her lover isDhirodhata and the sentiment is VipralambhaSringar the intense feeling of love not ful-filled by the meeting of the lover. '

VI MEGHMALAR RAGA.67. This Raga has spnmg from the

sky. He is dressed in dark-coloured gar-ments. He is white complexioned andwears a crown of coiled hair on the head.Being a soldier he holds a sword in the handand is of such a handsome appearance thathe subdues the hearts of all men. ThisRaga is sung by experts in music in beautifultones in the fourth part of the night in rainyseason.

RHETORICAL INTERPRETATION.The Nayak (hero) is Dhirprasant i.e.,

one possessing all the qualities of a Nayakand is of high birth. The Nayaika is anunmarried girl not bound by conventionalrules. The sentiment is Vipralambha

Sringar.TANKA RAGINI.

68. In order to avoid the heat of theaffliction of her heart, she is lying on alotus-made couch burning with the pains ofseparation from her lover and heaving deepsighs. The dominant note of this Ragini isKharaj and is sung at night in a rainyseason.

RHETORICAL INTERPRETATION.The Nayaika is a modest, polite and

faithful woman in her teens, who is expertin all the arts of pleasure and owing to theseparation from her lover, is afflicted atheart Her lover is Anukul or one favour-ably disposed towards her. The sentimentis Vipralambha Sringar.

MALARRAGINI 2. (lUus. Fig. 2.)69 & 70. She is of extremely delicate

white limbs and exuberant youth and lookssurpassingly lovely and charming. Shehas a lovely neck and charming voice,and is struggling with the anguishes of sepa-ration with utmost fortitude. She is playingbeautifully on a Vina (guitar) held in herhand, well remembering the good qualitiesof her lover but her face is covered withtears. This Ragini is sung in the Dhaivat-swar in the last three parts of the night inrainy season.

RHETORICAL INTERPRETATION.The Nayaika is a young passionate

woman endowed with the qualities of mod-esty, courtesy and extreme devotion to herhusband who has gone to a distant country onbusiness. Her lover (husband) is Anukul orone favourably disposed towards her. Thesentiment is intensely erotic but held incheck owing to the lover not being close by.

GURJARI RAGINI 3.71 & 72. This Ragini wears a red sari

and yellow corset and is exceedingly beauti-ful. Her waist is slender, her hair fine and

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

41/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

42/70

lOU

fifth of its kind that has been organised throughthe zeal and initiative of Mr. Cousins, who is nowthe Secretary of the Art Section of the 1921 Club.

I may perhaps add that the Art Section itself isfree from politics, though the Club is a distinctpolitical organisation.

The Exhibition rooms were very plainly and

tastefully set out. A white back-ground shows upthe seventy and odd representative pictures whichare mounted on simple white or coloured cardboardas the artistic necessities of the picture may de-mand. The pictures in groups (as in the case ofthe sketches by Mr. Haldar) were pinned on wood-en screens. The exhibition gave one the impressionof simplicity humility and repose.

Mr. Cousins, to whom I wrote for an inter-view, kindly received me at the Exhibition rooms,and I give below the full report of the interviewwhich vrill throw a flood of light on the art that isunfortunately little understood by Indiansthemselves.

Question. What is the fundamental differ-ence between the art of the West and of theNeo-Bengal School?

Answer. The answer to this question was,1 think, unconsciously given by two visitors to thegallery, both Europeans. One dismissed theentire collection as being stiff and uninteresting,with the possible exception of one picture thatof a man shotting an arrow at a pair of doves on atree. The other, evidently moved by somethingin the collection, passed slowly from picture topicture. I hazarded the question as to whether hecared for them. He replied: "They fascinateme." "Why?" 1 asked. "Because," said he," every one of them expresses soul." I think thatis just the difference. Western art has been giventhe Dharma of expressing the muscularity, vigourand emotion of life. The Bengal artists (indeed,one might say, all true Indian artists) are thenatural expressors of the higher mental and spiritu-al aspects of humanity and nature. Western surtrepresents things as they are viewed from the out-side. Eastern art interprets things from the inside.

Question. To a Western art-critic thecharacteristics of the Bengsd School appear to beits gloominess, its lack of courage and humour, anda very imperfect knowledge of drawing except inone or two isolated cases. Have these charges anybasis?

Answer. The " gloominess " is a matter oftaste

or, perhaps, I should rather say habit which

has become prejudice. Painting may be the directexpression of the artist's genius and environment,but it may also be the expression of some counter-balancing need. Western artists seek the shortsummer light because for eight months in the yearthey live in semi-darkness. Indian artists seekfor relief from the constant superfluity oflight and heat in the short but magicalmorning and evening hours, just after dawnand before sunset. I do not understand thecharge of " lack of courage " though, I think,

I understand the mental limitations wsee courage only in physical action,fail to see it in the exquisite calm exprsion of mental and spiritual vision. Humourthe comic paper variety is certainly not presentany extent in these pictures, save perhaps incase of Mr. G. N. Tagore's somewhat keen-edgesatires. But it appears to

methat humour

valuable in the West as a set-off to the tragicment which is inherent in the Western conceptioof Life and Death. Whereas in India the ideaLife as a continuous succession, of whichpresent life is only one phase, takes the tragedyof things. The Sanskrit drama, for example,the reason I have stated, has no tragediesTragedy and comedy belong to the lower slof the hill of life: the Bengal artists paint fromsummit. As to bad drawing, I remember hearthis charge levelled against AE in Irelandago. Yet, people used to come from Americaattend his exhibitions and carry his paintings has trophies. The pictures of the Bengal Sc

are not to be classified as " drawings." Theyvisual expressions of moods and visions ofsoul, in which there is a higher accuracy thanof the inch-tape. Many of the paintings aretomically normal, and indicate purpose inpictures which do not agree with the conventionahabit of the eye.

Question. Then, agjun, there is the chthat the artists of the Bengal School ignorerules of proportion in their drawing of theand of the hands. What is your own view regaing this?

Answer. My view is that a littleobservation and thought would put this chargeof court, as happened in my own case. I resenthe elongated eyes and snaky fingers of the Bepictures when I first saw them. But afterwardswhen I saw these same features on visiting BenI realised that I had been labouring under themental disability as most Europeans andIndians, in assuming that what I was familiarwas the normal and accurate, and that naturaany variation from it was abnormal and inaccurateThere is this also to be remembered thatthe artists are depicting Divinity and Suhumanity they revert to the ancient Shastricfor such depiction. Two excellent examplesthe difference between these methods werethe walls of the Exhibition, Dr. A. N. Tagor"Buddha" and his "Divine Craftsman: Vikarman " which was exhibited for the firstthis year in Calcutta. The first is a suprembeautiful expression of the calm of illumination.The proportions are perfectly normal. The seis built entirely on the so-called " false anatomBut this anatomy is that of the Shastras wprovide conventional idealistic form and measument for the expression of that which is beform and measurement. When one acceptsconvention, as one accepts the convention ofing in drama, one is then free to comprehend

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

43/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

44/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

45/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

46/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

47/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

48/70

106

girls, place on a decorative motif representing athrone, the happiest of the young wives of theiracquaintance, as an incarnation as it were of love andconnubial fidelity, with the object of securing anequal felicity in their own married lives and ofbeing inspired ^th similar ideas a worship ofthe housewife in excelsis which may appearstrange to our Western friends.

It is in no carping spirit that we mention afew very minor inaccuracies in transliteration andtranslation which we hope will receive theauthoress's attention when the second Edition ofthe book come to be published. ' BahadouliVrata ' (p. 37) should be ' Bhadouli Vrata ' and' Basoudara ' in p. 72 ' Vasoudhara.' In p. 26 whathas been accurately translated as ' la ceremonie despieds de Hari ' should be transliterated as ' Hari-charan Vrata ' and not as ' Harisharan Vrata.' Inp. 55 it is said of the young Moon

" Elle cherche son dieu soleilpar toute la terre "

In the originad text it is the Sun who goes in searchof his beloved as wrill appear from Mr. Tagore'sown Translation quoted above. At p. 31 the petalsof the Aubergine are described as faded and lan-guishing'K' fanes et languissants ') but in the Ben-gali original the leaves of the brinjal plant areclearly described as ' dhola dhola ' adjectiveswhich are used in common parlance tosignify leaves that are ' broad and luxurisuit.'

No coloured plate has been reproduced fromthe origined work to provide an example of colour

painting done in the Zenana, but we owe it to MKarpeles to add that an artist herself and ofordinary merit she has selected some of the vbest examples from Dr. Tagore's wide collectionillustrate the letter press.

It is needless to state that all the beautyAlponas and their associate cults all that ispoetry and art in them is due to the gracious psence of women and their soft and refininginfluence. Dr. Tagore has very clearly broughout the contrast in his account of Kulai Thakuceremony observed by young cowherd boyswhich representation of sound and - movemenreplaces the Alpona a mere ebullition in fact,boyish sportiveness, which has no art or artistryabout it.

Now that Dr. Tagore is the Bagesw^ariProfessor of Indian Art in the Calcutta University,may we not hope that an English edition ofvaluable work will be brought out under the apices of the University for the benefit of Engjish-knowing readers who have no acquaintance withBengali language and as a penitential coursestudy for those unfortuna'te post-graduate studentswho never had a modicum of art or aestheticstheir curricul^^ and at ^vhom even the genDr. Tagore has a fling, so that they may learnrespect at least the artistic endowment ofwomanhood of Bengal, even if they cannot brithemselves to sit at the feet of their young wivand sisters to learn the first principles of Hindecorative art.

G. D. S

DANCING AND THE DRAMA, EAST AND WEST, BY STELLA BLOCH, WITH AN INTRODUC-

TION BY ANArjIDA COOMARASWAMY, 13 PP., ILLUSTRATED. ORIENTALIA,NEW YORK, 1922.THIS is a brilliant little pamphlet discussing

the essence and ideals of the Eastern andWestern Theatre, and is the. result of herrecent tour through the Far East and India.

The title is very significant; for, in the East, Danc-ing and the Drama are not two distinct things: itis in the medium of dances and gestures that theDrauna unfolds itself. Miss Bloch, whose brilliantlittle essays are already familiar to our readers, thuscharacterises the structure of an ideal drama asgleaned from the East : " It is only at the heightof a culture that the architecture of true Drauna up-

lifts itself ; at the moment when temples are builtand the epic arises ; when life is seen in legends andthese legends become symbols; and the symbols arecarved on stones, and the stones built into a palacefor the king or the gods. It is then that the wallsof a temple are the manuscript of life itself. Theepic rushes through the lips of every bard and noneintrudes a personal grace upon the divine parable.

" Sacrifices and rites are performed accordingto formalities laid down by the gods themselves. Itis in this devout spirit that the carver learns theraft of image-making, the singer prays, and the

philosopher expounds the great principle. It isthis spirit that the actor advances upon the staghis whole constitution inspired by faith in the actiowhich he shzdl take part in unfolding. ForDramatist, as for eJl other craftsmen, the themealready fixed and only calls for orchestration :manner of its presentation is a tradition, andfunction lies in directing the players accordingthat lore w^hich accompanies the performancethe epic. His work is that of one, who, in obedienceto an architect, supervises the building of a houand indicates to the workmen every detail of p

cedure. Whence arises the superstition that a pmerely set down in words to be spoken is DramaThe Drama has no reserves and makes use of evehuman device of expression. All the Arts are inservice. The Dramatist must be learned in theand combination of these according to the severebiws set down by the gods.

" It is for the multifarious expressions of TGreat Tale that the theatre exists : for the humpresentation of the adventures of gods and gremen. No imitation of ev^-yday life shall be represented- here only the doings of fvinities.

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

49/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

50/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

51/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

52/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

53/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

54/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

55/70

109

Our artist introduced cubism in India, and atonce cubism shows another aspect. It is not thestatic and crystallic, but the animate and dynamicwhich crystalize into cubes, cones, etc. Here thecubes do not build up a systematic structure, butthey express the radiating, turbulent, hovering orpacified forces of inner experience. The designof every composition therefore is based on a dia-gonal movement which connects the right cornerabove with the left corner below. Emotion thus istransformed into diagonal composition, which coin-cides with the brush stroke. In Europe on the otherhand the characteristic feature of a cubist designconsists in its static vertical-horizontal arrangement.

The transformation of cubism, as a principleof composition from a static order into an expres-sive motive is the artist's contribution to Indian artand to cubism alike.

Notwithstanding however the intrinsic meritof these first cubistic contributions of the artist thequestion has to be faced how far the cubist formulais suited to the Indian expression. The answer isgiven by the compositions themselves. Throughthe dynamic conception of a diagonal design theylead to an unconscious, but steadily prog,ressingdestruction of cubism.

Indian cubism is a paradox, for the ever moved,flowing life of an Indian work of art is opposite tocubism which essentially is crystallized static.Forms of difiFerent civilisations are incompatible.

Modern Western art evolves formulae for ren-dering a psychical reality. The important part ofit is the consciousness of this reality and not thefeatures of the formulae. This consciousness how-ever confirmed by Western psycho-analysis belongsto the whole world and no expression of modern

spiritual life can escape it, although within everycivilisation it has its own trend.

Cubism therefore has its mission in Indian art,if it becomes absorbed by it; for it does not meananything else but the newly awakened conscious-ness of spiritual reality which knocks at the door ofIn(an art, disguised in a strange form. In orderto enter, it has to throw off the masque.

STELLA KRAMRISCH. Hi

EUROPEAN INFLUENCE ON MODERNINDIAN ART. In an interesting littleparagraph a local contemporary has raisedthe question whether it is possible for a

modern Indian artist to avoid and ignore theinfluence of Europe in his works. " There are thosewho seek in the work of Indian artists the subtleinfluence of the East and bewail the introduction ofwhat they consider a factor which detracts muchfrom the value of the pictures as expressions of thenational life of the Indians. It may, however, bequestioned if it is possible for an artist to ignorethe influence of the West, or of any other country,if he comes under it. In Japan, Western influence,in spite of the conscious efforts of the leaders inthe world of art, is asserting itself, and

is not felt in a palpable manner is China;but Chinese artists have not come into intimateChina ; but Chinese artists have not come in intimatecontact with the West." The question ofinfluence depends on the mental and physicalenvironment of the artist. It is a well known factthat a considerable portion of India is living inabsolute detachment and untouched by the contactof European ideas \%^ich British dominion has im-ported into India. In the world of the arts andcrafts it is yet possible to find a few craftsmenstill working each in his old indigenous way true tothe traditional spirit and method of his ancestorswithout any influence from Europe suchas has affected his brethren brought upin the Government Schools of Art. Evenamong the artists, who live in the Presidencytowns in intimate contact with Europeanideas and breathe so to speak the typicalmodern atmosphere impregnated with foreignideas (using the word foreign in a harmless sense),it is not difficult to find tendencies and inclinationswhich owe nothing to European influence and areevolved from the artist's individual and nationaltemperament. Where his contact with Europeanideas has brought about a change in his own mentalcalibre it may be possible, though hardly com-mendable for him to suppress the colour, of hisown mind. In indicating the influence of Europein the most sincere form of flattery many anIndian artist has performed the so-called impos-sible feat of suppressing the colour, the texture andthe mood of his ov/n individual and national tem-perament and has produced works in which theevidence of an Indian hand or the expression ofan Indian mind has completely disappeiured. As apiece of psychological jugglery such a phenomenon

has no equal in any other part of the world butalso as a piece of artistic insincerity and hypocrisyit has also no rival. The crux of the whole questionlies in an intellectual and spiritual synthesis ofEastern and Western culture in which the ques-tion of " influence " is an irrelevant and misleadingtopic. The word " influence " inevitably suggests adomination or the supremacy of one over the other.In \ the field of art to produce worksunder the domination of an outside in-fluence is the worst form of aestheticcatastrophe. The freedom of the indivi-duaJ and the sincerity of the form of expression isthe first condition of the production of a work ofart. The moment the outside influence is absorbed

and made part of one's own mentsJ equipment itceases to be an influence because it ceases todominate on the mind or sterilise it it has becomean enriching factor, a fertilising medium. Thebest minds of all countries are awaiting to seethe modern Indian mind evolve a new form enrichedbut not dominated by the thought and culture of theWest. If India is to benefit by her contact withnew ideas she must absorb, assimilate, " conquerand make them her own. Her own mindmust act and react upon them and nation-alise them. In the field of art, the opportunity

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

56/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

57/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

58/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

59/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

60/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

61/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

62/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

63/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

64/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

65/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

66/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

67/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

68/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

69/70

-

8/6/2019 Rupam_11

70/70