88013__911180898

-

Upload

ludovic-fansten -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

0

Transcript of 88013__911180898

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

1/21

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

This article was downloaded by:

On: 29 June 2010

Access details: Access Details: Free Access

Publisher Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-

41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Environmental PoliticsPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713635072

Cross-movement activism: a cognitive perspective on the global justiceactivities of US environmental NGOsJoAnn Carmina; Elizabeth Bastba Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA b

International Program, Friends of the Earth US, USA

To cite this Article Carmin, JoAnn and Bast, Elizabeth(2009) 'Cross-movement activism: a cognitive perspective on theglobal justice activities of US environmental NGOs', Environmental Politics, 18: 3, 351 370

To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09644010902823550URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09644010902823550

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial orsystematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply ordistribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contentswill be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug dosesshould be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss,

actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directlyor indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713635072http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09644010902823550http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdfhttp://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdfhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09644010902823550http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713635072 -

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

2/21

Cross-movement activism: a cognitive perspective on the global

justice activities of US environmental NGOs

JoAnn Carmina* and Elizabeth Bastb

aDepartment of Urban Studies and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology,USA; bInternational Program, Friends of the Earth US, USA

Environmental NGOs often create new campaigns or extend their ongoingactivities from the principal issue arena in which they work to othersubstantive domains. Although this is a common practice, scholars havenot assessed how NGOs position their work within different arenas orwhether these activities represent an extension of or deviation from anorganisations mission and values. To understand the nature of cross-movement activism, the global justice activities of four environmentalorganisations are examined. All four participated in the global justicemovement in ways that reflected their long-standing interpretations of the

source of environmental problems and their deeply-held views of how toaddress these problems. Thus the cross-movement activism of environ-mental NGOs not only draws on their longstanding repertoires of action,but is consistent with their mission and core values.

Keywords: global justice; environmental organisations; social movements;frames; tactics

The rapid globalisation of the world economy over the last 30 years, along with

the promotion of export-oriented economies and free trade by international

institutions and multinational corporations, has engendered criticism from

many progressive movements, organisations, groups, and individuals. The rise

of activism around the issue of economic globalisation and its impacts has

become known as the global justice movement. The justice label reflects the

idea that the economic policies promoted by institutions governing trade and

development, in addition to the global business model being pushed by

multinational corporations, are increasing the level of inequality between rich

and poor on a global scale. Accordingly, global justice activists typically focus

their efforts on one or more of four primary targets: international financial

*Corresponding author. Email: [email protected]

Environmental Politics

Vol. 18, No. 3, May 2009, 351370

ISSN 0964-4016 print/ISSN 1743-8934 online

2009 Taylor & Francis

DOI: 10.1080/09644010902823550

http://www.informaworld.com

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

3/21

institutions, trade organisations and rules, multinational corporations, and the

governments of wealthy countries.

As the global justice movement has matured, the number of individuals and

organisations that identify with its goals has increased. For example, the WorldSocial Forum, a regular gathering, now counts attendance in the tens of

thousands. Participants in the Forum, and in the movement more broadly, not

only include grassroots and largely informal actors, but a wide variety of

formalised and professionalised nongovernmental organisations (NGOs).

Some of these formal NGOs were founded with the intent of working on

global justice. Most, however, were established to address other issues. Cross-

movement activism refers to those situations in which an NGO founded to

work in one issue arena extends its efforts to a different substantive domain.

Just as environmental NGOs are central actors in the global justice movement,they also contribute to a variety of other issue arenas ranging from labour

equity to peace to human rights (Rose 2000, Obach 2004, Rootes 2005).

Although many environmental NGOs engage in cross-movement activism,

scholars have not investigated how organisations position their efforts within

alternative movements or the extent to which these activities are aligned with

NGOs organisational mission and goals. Gaining insight into the basis of cross-

movement activity is important given that the prominence of environmental

NGOs in domestic and global governance in recent years has been accompanied

by challenges to their legitimacy the perception or assumption that the actionsof an entity are desirable, proper (Suchman 1995, p. 574) as social and political

actors. In general, NGOs are empowered to take action on the basis that their

efforts benefit society and address issues of public concern (Keane 1988, Cohen

and Arato 1992, Edwards and Hulme 1996, 2003). The way each NGO seeks to

enact this mandate is expressed by its mission and reflected in its values. If

working in a different substantive arena represents a departure from these core

attributes, then an environmental NGO may undermine its legitimacy.

To understand how they situate their activism within alternative issue

arenas and the legitimacy of this behaviour, we examine the relationship of one

set of cognitive factors diagnostic and prognostic frames to the cross-

movement activities of environmental NGOs. This research draws on

interviews with representatives from four environmental organisations in the

United States as a means to understand how frames shaped their global justice

activism. The patterns thus found extend our knowledge of the activities of

environmental NGOs by demonstrating that when it comes to cross-movement

activism, these organisations seek cognitive alignment and, as such, orient their

efforts within alternative issue arenas in ways that are aligned with the values

and aims embedded in their diagnostic and prognostic frames.

Structural and cognitive dimensions of cross-movement activities

Social movement theorists suggest that, in their early stages, nascent social

movements will take root in existing organisations formed for other purposes.

352 J. Carmin and E. Bast

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

4/21

As movements mature, it is expected that organisations dedicated to the specific

cause will emerge (Tarrow 1998). In contrast to this theorised trend, many

contemporary movements rely on the ongoing participation of organisations and

actors from other issue arenas. Thus the global justice movement has beencharacterised as a movement composed of a loose network of organisations

founded with various purposes but united by a common goal (della Porta 2007).

Cross-movement activities in the global justice arena, as well as in other

substantive domains, tend to take one of several forms. These include

participating in formal coalitions and building informal alliances comprised of

organisations from across issue arenas (McCarthy 2005). A further approach,

and our focus here, is when NGOs take independent action and extend their

existing activities or establish new campaigns in other or emerging domains.

Social movement scholars associate both structural and cognitive factorswith the extension of organisational activism into new issue arenas. Although

most studies look at participation in coalitions, these findings provide a point

of departure for understanding cross-movement activism more broadly. The

most relevant structural explanations that apply from coalition research are

that participation takes place when an organisation believes it can make a

distinctive contribution or can better achieve its own goals. When NGOs

engage new issue arenas, they typically overlap with their pre-existing efforts

(Rose 2000, Van Dyke 2003, Obach 2004, della Porta 2005, Rootes 2005, Smith

and Bandy 2005). By extending, rather than deviating from current practices,an organisation may be able to bring its distinct capabilities to the other

movement and, in the process, mobilise a broader base of support for its work

(Zald and McCarthy 1980, Hathaway and Meyer 1997). Cross-movement

activities also may help NGOs develop new niches for their activism (Levitsky

2007) and tap more diverse pools of resources to support their work

(Hathaway and Meyer 1997, Arnold 1994, Brown and Fox 2001). Further,

cross-movement activism may make it possible for an NGO to increase the

efficacy of its action. By extending its work to other movements, an

organisation can benefit from the achievements and activities of other

NGOs, particularly those employing different repertoires of action and

engaging different targets (Zald and McCarthy 1980, Staggenborg 1986,

Hathaway and Meyer 1997, Tarrow 1998).

Capitalising on differentiation and taking advantage of new opportunities

are two of the structural motivations associated with NGO participation in

cross-movement activism. From a cognitive perspective, however, it is not

differentiation but similarities and shared perspectives that motivate NGOs to

extend their activism to new issue arenas (McCarthy 2005), and explain where

within the new movement they position their work. For instance, concerns

about different dimensions of the same issue or the presence of a commonenemy often serve as catalysts for NGOs to pursue a course of action

(Gerhards and Rucht 1992, McCammon and Campbell 2002, Van Dyke 2003,

Reese 2005). An equally important factor is shared values. Individual

environmental NGOs tend to have collectively held values ranging from the

Environmental Politics 353

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

5/21

desired relationship of humans to nature to the appropriate role of political

authority (Dalton 1994, Dreiling and Wolf 2001, Carmin and Balser 2002).

Values such as these shape organisational assessments of external conditions

and influence strategic and operational decisions. Given the centrality andcritical nature of core values, when determining whether or not to address a

new issue or extend the substantive arena in which they work, most NGOs will

make decisions that reflect and reinforce these critical factors (Schein 1985,

Oliver and Johnston 2000, Zald 2000, Carmin and Balser 2002).

The deeply held values of NGOs, as well as their missions, are reflected in

the way in which they frame problems and issues. Framing refers to the

development of cognitive models that an organisation uses to simplify and

make sense of its experience. NGOs also use frames to communicate their

views and grievances to others (Snow and Benford 1988). Diagnostic andprognostic frames serve important functions in shaping collective under-

standing and action. Diagnostic frames help NGOs identify the source of the

problems they seek to address while prognostic frames provide means for

understanding what needs to be done to resolve these problems, including

delimiting appropriate targets and tactics (Snow and Benford 1988, Benford

and Snow 2000, Snow 2004). Given the orientation and interpretations driving

each of them, diagnostic frames generally reflect shared values while prognostic

frames tend to be more closely linked to the organisational mission and aims.

Consequently, frames provide a bridge between cognition and action as theynot only shape understanding of the sources of problems, but provide a means

of action for problem resolution. Given the import of cognitive alignment, it is

likely that these diagnoses and prognoses influence where an NGO positions its

activism when it extends its work to a new movement.

Studying the global justice activities of US environmental NGOs

To understand how NGOs situate their activities within other movements and

determine whether cross-movement activism represents an extension of or

diversion from organisational mission and values, we investigated the relation-

ship between the diagnostic and prognostic frames of four professional

environmental movement organisations and their global justice activities. In

selecting these organisations, we limited the population to environmental NGOs

that were registered in the US, so that the national context was held constant.

Drawing on the definition of professional NGOs advanced by McCarthy and

Zald (1977), we only considered organisations that were in existence for at least 15

years, were run by full-time, paid employees, and were supported by grants or by

dues-paying members who were not involved in routine management, decision-

making, or programmatic activities. We further narrowed the population byrequiring that the organisations have an environmental focus as evidenced by

their mission statement and be engaged in some form of global justice activism.

Our selection was limited since most of the large conservation organisations do

not forge ties to other movements and, at the time of this study, none was engaged

354 J. Carmin and E. Bast

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

6/21

in global justice activism (cf. Nordhaus and Shellenbergers (2007) critique of the

US environmental movement). From the organisations that met our two criteria,

we sought to identify four that varied along the dimensions single versus multi-

issue and US affiliate of an international organisation versus national US-basedorganisations without international branches.

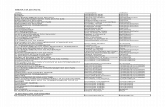

As summarised in Table 1, the multi-issue affiliates of international

organisations included in this research were Friends of the Earth (FoE) US and

Greenpeace USA. The two single-issue, domestic organisations were Interna-

tional Rivers (IR) and Rainforest Action Network (RAN). All of the

organisations have engaged in protest as a tactic for political change, but

RAN and Greenpeace are known specifically for their use of non-violent direct

action, while IR and FoE rely more on policy-oriented analysis and advocacy.

Interviews were conducted with a minimum of three representatives fromeach of the organisations. Individual respondents were selected because they

were knowledgeable about the development and activities of the organisations

global justice work. Most of the interviews were conducted in person, but in

two instances we conducted telephone interviews and in another we relied on

an email exchange. In each, a series of questions was asked regarding the core

values and beliefs that characterise the organisation, the ways in which the

organisation was involved in global justice activism, and its perceived

contributions to the movement. The in-person and telephone interviews

ranged from 45 to 90 minutes. All the interviews were recorded and therecordings were transcribed. Interviews and email exchange were supplemented

with information posted on organisation websites, published studies and

descriptions of the organisations, newspaper articles, and archival materials.

We reviewed the transcripts and secondary materials with the goal of

identifying statements and passages related to frames. Diagnostic frames were

regarded as statements that reflect the perceived sources of environmental

problems while prognostic frames were those related to how the problem

should be resolved. Since we were looking for collectively held frames, we

Table 1. Characteristics of participating organisations.

Friends ofthe Earth US(FoE US)

GreenpeaceUSA

InternationalRivers

RainforestActionNetwork (RAN)

Year offounding

1969 1979 1985 1985

Single/multi-issue

Multi-issue Multi-issue Single issue Singleissue

US affiliate Domesticaffiliate ofinternationalNGO

Domesticaffiliate ofinternationalNGO

Domesticorganisationwith nointernationalbranches

Domesticorganisationwith nointernationalbranches

Environmental Politics 355

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

7/21

triangulated across the interviews and documents to identify consistent

perspectives. Finally, we looked for relationships between stated diagnoses,

prognoses, and action. Once these patterns were identified, we organised the

findings for each organisation as short case narratives.

The global justice activities of four environmental NGOs

The sections that follow present brief narratives of the global justice activities

of Friends of the Earth US, Greenpeace USA, International Rivers Network,

and Rainforest Action Network. Each case presents the diagnosis or dominant

views that staff members hold regarding the sources of environmental problems

and the prognosis that is advanced. It also illustrates how these frames reflect

environmental values and organisational mission and, in the process, establisha basis for the organisations global justice activism.

Friends of the Earth US

Friends of the Earth (FoE) was founded in 1969 in San Francisco by David

Brower. Brower, who had just resigned as executive director of the Sierra Club,

wanted to establish a new environmental organisation that would be

international, aggressive, and uncompromising (Carmin and Balser 2002).

Building on this vision, FoE developed a reputation as a hard-hitting politicalorganisation with an aggressive style. In its early years, FoE launched

campaigns against clothing made from wild furs and feathers, dams and other

projects that threatened rivers, supersonic air transport, and whaling (FoE

2007a).

In 1988, FoE US, the Oceanic Society, and the Environmental Policy

Institute, an organisation established in 1972 by former FoE staff members,

merged under the FoE label. Over the next two years, the re-formed FoE

redefined its priorities and began to focus on three major areas: toxics and

pollution in food, air, water, and soil; poverty, inequality, and war; and control

of new technologies. Drawing on the approaches traditionally used by each of

the now merged organisations, FoE relied on a breadth of tactics, including

policy analysis and reports, lobbying, media work, and direct action. The

breadth of the campaigns and tactics employed after the merger was indicative

of the transformation that was taking place within the organisation. As

exemplified in the name of its initial newsletter, Not Man Apart, from the outset

FoE was founded on the premise that humans are not separate from nature

(FoE 1992) and that civilisation must respect natural resources (Oakes 1980).

While this perspective remained, it was expanded to more explicitly incorporate

human-centred views derived from the Environmental Policy Institute.Since the merger with the Environmental Policy Institute, FoE US has

distinguished itself within the American environmental movement by its

emphasis on the nexus between environmental problems and economics. In its

international work in particular, FoE US has increasingly addressed human

356 J. Carmin and E. Bast

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

8/21

rights and social equity, particularly as the Friends of the Earth International

network has grown to include more groups from the global South. The view

that natural and social systems are interrelated, and of equal importance,

however, has been a consistent characteristic of the organisation:

[At] Friends of the Earth . . . we take an unusual stance among environmentalgroups, in that we focus almost as much on social justice issues as onenvironmental issues, and we are very interested in the intersections betweenenvironmental and social issues. (FoE 2004b)

While these views generally are maintained across the organisation, they are

particularly evident in the diagnoses that staff members working on

international campaigns make about the source of environmental degradation

and social inequities. They concluded that these problems could be attributedto prevailing economic policies, particularly inequalities in the development

process. While there are notable variations across the FoE network (Doherty

2006), in keeping with many of the member groups (Rootes 2006), FoE US has

made a commitment to challenge the current model of economic and

corporate globalisation, and promote solutions that will help to create

environmentally sustainable and socially just societies (FoE 2007b).

It was a natural step from the diagnosis that a faulty model of economic

development is in place, to the view that addressing the root cause of

environmental problems requires targeting development institutions andpolicies. International activism within FoE US that is based on these

diagnostic and prognostic frames stretches back over several decades. For

instance, after the merger in 1988, a coalition being led by the Environmental

Policy Institute to reform the World Bank became a FoE campaign that was

expanded to the IMF and other multilateral development banks. While FoE

US has since continued to target financial institutions, it extended its work to

trade policy issues in the early 1990s when members realised that the then

proposed North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) would not only

threaten a number of US environmental regulations, but would propagate the

development model that they were working to oppose.

The deeply entrenched view that the development process is a critical source

of environmental problems, and therefore that environment can not be

separated from human rights and social equity, shapes the specific ways in

which FoE engages the global justice movement. Whether focusing on financial

institutions or trade rules or multinational corporations when they propose

activities viewed as environmentally unsound and socially unjust staff

members of FoE regard these targets as important means for advancing the

organisations integrated mission:

I think on a gut level, we go after the root causes of environmental destruction.We go after corporate power and we go after economic incentives that create aprofit for people to exploit the environment. So, theres a strong justicecomponent that underpins what we do. (FoE 2004a)

Environmental Politics 357

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

9/21

Consideration of environmental degradation in the context of social justice

leads staff members working on international issues to place emphasis on

ensuring that the rights and interests of people affected by international

institutions, trade deals, and government actions are appropriately advanced.While employing their traditional range of tactics, including policy reports,

lobbying, and direct action, rather than imposing a particular approach, staff

members leading global justice-related campaigns seek to implement their values

by adopting FoE Internationals commitment to local voice (Rootes 2006). As a

result, international campaigners in FoE US work closely with national groups in

the FoE network and with civil society groups in developing countries to set the

agenda and shape the approach that is taken. By having strong ties to developing

country communities and grassroots groups, representatives from FoE US gain

greater understanding of the social and economic difficulties faced by developingcountry populations issues that in the global South are clearly intertwined with

environmental destruction and the organisation incorporates those issues into

its global justice outlook and work.

Greenpeace USA

Jim and Marie Bohlen and Irving and Dorothy Stowe were Americans who

moved to Canada for political reasons, including opposition to US

involvement in the Vietnam War. When they heard about the US governmentsplans to test nuclear bombs in the Aleutian Islands, Marie Bohlen suggested

that they adopt the Quaker idea of bearing witness and sail a ship to the

detonation site as a form a protest. They agreed on this and planned to take

action under the auspices of the Sierra Club. However, the Sierra Club office in

the US disapproved. Rather than be dissuaded, the Bohlens and Stowes, along

with Paul Cote, formed the Dont Make a Wave Committee and, in 1970,

started planning for the voyage. During this time the group began calling itself

Greenpeace. The committee officially changed its name to the Greenpeace

Foundation in 1972 and, over the years, expanded from a small group with a

strict focus on nuclear testing to an international organisation that works on a

range of environmental issues (Brown and May 1991; Bohlen 2001; Carmin

and Balser 2002).

Greenpeace USA was established in 1975, and officially recognised in 1979

(Brown and May 1991). In its early years, Greenpeace USA engaged in direct

action campaigns on nuclear dumping issues and toxic waste, employing tactics

such as plugging outflow pipes and creating blockades to target local and

national governments. By 1981, the organisation began to explicitly acknowl-

edge corporations as the source of environmental degradation. However, it was

not until 1989, when activists occupied a water tower, hung a banner, andblocked the transport of chlorofluorocarbons (CFC) at the Dupont Plant in

Deepwater, New Jersey, that Greenpeace USA began to focus its direct action

against corporations rather than relying solely on pressuring governments into

promulgating stricter regulations.

358 J. Carmin and E. Bast

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

10/21

Greenpeace USA aligns its efforts with those of Greenpeace International

and adopts the broader organisational mission to expose global environmental

problems, and to force the solutions which are essential to a green and peaceful

future. Greenpeace Internationals goal is to ensure the ability of the earth tonurture life in all its diversity (Greenpeace 2007). The Greenpeace mission also

acknowledges the interconnectedness of all species, suggesting that humans are

just one of the many forms of life on the planet (Greenpeace 2007). As a result,

the approach that staff members take toward environmental protection

typically includes a critique of power inequities based on the perspective that

neither humans nor the environment should be subservient to the other

(Carmin and Balser 2002). The emphasis on balancing the concerns of all

species has led the organisation to be uncompromising in the priority it places

on protecting environmental quality:

I think there are two schools of thought within the environmental movement . . .Its either the environment has an intrinsic value on its own and deserves to beprotected for that reason or, on the other hand, its that humans are stewards ofthe environment. And . . . for Greenpeace . . . it has an intrinsic value and webelieve that it has a right to be protected on its own without any compromise.(Greenpeace 2004a)

Greenpeace USA locates the source of environmental problems in an

inequitable distribution of power. In its earliest years, the organisation asso-ciated this inequity with governments. However, with the rise of multinational

corporations and the spread of economic globalisation, Greenpeace USA has

become increasingly sensitised to the impact of corporate power and

domination on the environment, and, as one campaigner noted (2004b),

supports the views and approaches in this domain that are advanced by

Greenpeace International:

Greenpeace opposes the current form of globalization that is increasing corporatepower. Trade liberalization at all costs leads to further environmental and social

inequity and undermines democratic rights. It does not lead to povertyalleviation . . . In promoting global environmental standards and opposingtransnational corporations double standards, we advocate a new approach:forms of global governance, including trade and finance, that are open,transparent, fair, equitable and under democratic control. (Greenpeace 2001,p. 21)

As this suggests, staff members of Greenpeace USA believe that

corporate practices are fostering policies such as trade liberalisation that, in

turn, not only harm the environment, but undermine poverty alleviation.

This diagnosis linking environmental problems to power differentials istightly coupled with the prognosis that change will only be realised by

exposing the negative impacts of multinational corporations. Accordingly,

Greenpeace USA primarily focuses its global justice efforts on anti-corporate

activities.

Environmental Politics 359

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

11/21

Greenpeace USA has been viewed by many activists and organisations as

keeping its distance from the global justice movement. However, as one

campaigner notes, we are not a part of the anti-globalization movement in the

opinion of many, but we are against the current model of globalization(Greenpeace 2004b). While the relationship may not be explicit or formalised,

this stance has resulted in the organisation engaging in activism and developing

ties to the global justice movement. According to one campaigner (2004b), to

the extent that Greenpeace USA has engaged in global justice activities, the

organisations focus on consolidated power and corporate hegemony has

resulted in it aligning its activities with those of Greenpeace International,

primarily by engaging the anti-corporate stream of global justice activism.

[Greenpeace] has always been a leading voice for environmental protection overprofit, but the organization has also sensed a shift that has occurred in the contextof globalization . . . in recent years, with the increasing globalization ofeconomies, we have also found that corporations have globalized their methodsof profit, monopoly and environmental destruction. (Greenpeace 2001, p. 21)

While corporations are the organisations primary target and link to the global

justice movement, Greenpeace USA still engages in activities that strive to

change the policies of the US government as it remains one of the most

powerful governments in the world and therefore is viewed as an appropriate

target. For example, in 2000 it participated in organisation-wide efforts topressure the US and G8 governments to implement their commitments to

sustainable forest management (Greenpeace 2000). The organisation has also

pushed for President Bush to join forces with the other G8 countries to stop

global warming (Greenpeace 2007).

Greenpeace is renowned for engaging its targets by means of non-violent

direct action. The early Greenpeace idea of sailing a ship to the Aleutians came

from the Quaker practice of bearing witness to an injustice the practice of

observing the unjust action so as to be aware of what occurred and to take

responsibility for that knowledge rather than maintaining ignorance. This

concept of bearing witness is still very much connected with Greenpeace today,

where non-violent direct action is used to communicate and raise awareness of

environmental problems. While Greenpeace uses media extensively, and has

also expanded to use scientific analysis, lobbying, and litigation, the use of

direct action has played out across their campaigns, including those addressing

global justice.

International Rivers

Founded in 1985, International Rivers (IR) was one of the earliest projects ofEarth Island Institute, an organisation founded by David Brower in 1982. IR

began as an all-volunteer group of veteran activists concerned about the

impacts of dams. Although many of the founding cadre had significant

environmental experience, their efforts to create a network of river activists

360 J. Carmin and E. Bast

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

12/21

throughout the world led them to develop new insights into both the

environmental and social implications of development projects.

The organization was started by people who had experience fighting big damprojects in the United States . . . And upon our first international conference, [we]very quickly [learned] that large scale river damming projects were being built allover the developing world, and that the impacts were often even far worse thatthey had been in the United States. And the immediate understanding of thoseimpacts had a lot to do with the environment and a lot to do with loss of rightsassociated with people who were being forcibly displaced, or who were losingtheir land, or who were suffering the consequences of these projects. (IR 2004b)

In 1989, IR started to employ a full time, paid staff of activists trained in a

variety of social and natural science disciplines (IR 2004c). By the early 1990s, theorganisation had become active in countries throughout the world. IR started

working in China in 1991 when it attempted to halt international financing of the

Three Gorges Dam. In the early 1990s, members also worked to stop the Arun

hydroelectric project in Nepal and the Lesotho Highlands Water Project, the

largest infrastructure project in Africa. Over the years that followed, IR

continued to provide support to communities and local grassroots groups

worldwide to protect rivers and watersheds and to stop large dam projects, as well

as to change policies and practices of banks and other funding agencies.

Building on the insights gained from their first international conference,most of IRs work is driven by the idea that the construction of large dams

poses more than simply environmental problems. As indicated in IRs mission

statement, the organisation maintains that impacts on environmental quality

often are accompanied by abuses of social justice and human rights:

IRs mission is to halt and reverse the degradation of river systems; to supportlocal communities in protecting and restoring the well-being of the people,cultures and ecosystems that depend on rivers; to promote sustainable,environmentally sound alternatives to damming and channeling rivers; to foster

greater understanding, awareness and respect for rivers; to support the worldwidestruggle for environmental integrity, social justice and human rights; and toensure that our work is exemplary of responsible and effective global action onenvironmental issues. (IR 2004c)

IR locates the problems stemming from development not in the projects per se,

but in the economic system on which they are based:

We saw these projects, while problematic on their face, were also indicators ofsomething else. They were indicators of a particular model of economicdevelopment that consistently underserved poor populations, consistentlyunderserved indigenous people, consistently underserved women, and this wasnot a coincidence. (IR 2004b)

Since members attribute environmental problems and social injustice to the

rise of neoliberal policies, they frequently target international financial

Environmental Politics 361

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

13/21

institutions, including the World Bank and IMF. According to one staff

member, this focus grew out of the realisation that the World Bank is a huge

influence, because they really have been the primary funder of large dams, the

builder of large dams for decades (IR 2004a). Between 1989 and 1996, one waythat the organisation worked to hold these institutions accountable was to

produce the magazine Bank Check Quarterly, which focused on the activities

and politics of the World Bank and the IMF. Although the organisation had a

stated focus on rivers and dams, the magazine was dedicated to issues related

to economic globalisation. More recently, IR has continued its work

campaigning against the World Bank for its part in financing dams, while

expanding its range of targets to include private banks and export credit

agencies for their part in financing destructive dams in developing countries

(IR 2004b).IR has engaged in the stream of global justice activism that targets

international financial institutions. In addition to focusing on these institutions

directly, it also strives to achieve its global justice goals by supporting local

organisations and communities that seek to alter the behaviour of these

institutions. Members maintain that working with local communities is a

critical aspect for both understanding and addressing the environmental and

human rights issues associated with large dams and river infrastructure

projects:

As an international NGO what were trying to do is to support the work of localorganizations that are working on different efforts to protect the rivers and thepeople and life that depend on rivers. So . . . the campaigns arent strictlyenvironmental, nor are they strictly human rights oriented, nor are they strictlysocially oriented, but theyre a real combination of those things. (IR 2004b)

Members of IR employ a variety of tactics in order to support groups on the

ground, including writing reports, publications, lobbying the World Bank,

protesting, and boycotting companies. These approaches to understanding

local perspectives and supporting communities in their opposition to dams and

river projects are integral aspects of all of IRs campaigns, including those

focusing on global justice.

Rainforest Action Network

Rainforest Action Network (RAN) was founded by Randy Hayes in 1985.

Like IR, RAN initially was a project of David Browers Earth Island Institute

that developed into an autonomous organisation. As the name suggests, the

initial intent of the organisation was to cultivate a network among activists

working to preserve rainforests. In pursuit of this goal, one of RANs earliestactivities was to organise an international conference. This was attended by

representatives from 35 organisations from around the world. During the

course of the meeting, these organisations worked together to devise a plan of

action for rainforest protection (RAN 2007).

362 J. Carmin and E. Bast

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

14/21

Over time, RANs work has increasingly focused on US corporate targets.

However, the organisations Old Growth campaign to protect forests and its

Global Finance Campaign targeting private banks, in particular, maintain

strong links with civil society groups and activists in other countries, eitherwhere forests are being destroyed or where bank-financed projects are causing

environmental harm. As indicated in the organisations mission statement,

since its inception, RAN has campaigned:

for the forests, their inhabitants and the natural systems that sustain life bytransforming the global marketplace through grassroots organizing, educationand non-violent direct action. (RAN 2007)

The protection of forests is central to RANs mission. In seeking to realise thisgoal, members of the organisation determined that corporations pose the

greatest single threat to rainforests and old growth forests throughout the

world. As noted by one staff member, this view is based on their assessment

that corporations directly engage in extractive practices, fund tree harvesting,

and contribute significantly to climate change through pollution:

Our primary purpose has been to save the worlds last remaining rainforests andpreserve the rights of their inhabitants, and our strategy for doing that is bygetting US corporations to take responsibility for what theyre buying and

to make sure they arent contributing to the destruction of rainforests. (RAN2004a)

Given the diagnosis that corporations are a major source of forest

destruction, the organisation focuses on altering their practices (RAN 2004b).

RANs first, and highly successful, direct action campaign was held in 1985

when the organisation led a boycott against Burger King for its importation of

inexpensive beef from tropical countries where rainforests were being clear-

cut in order to create pasture for cattle to graze (RAN 2007). RAN followed

this campaign with actions against Scott Paper, Conoco, and Texaco. In the

late 1990s, RAN turned its campaigns against corporate logging companies,

including Mitsubishi, MacMillan-Bloedel and Georgia-Pacific (Motavalli

1997). RAN also launched a campaign that targeted Home Depot, the

largest retailer of wood products in the world, to deter the company from

selling timber that was harvested from endangered forests (Ring 2000).

RAN has more recently targeted Boise Cascade and Weyerhauser to pressure

them to eliminate wood and paper products from endangered forests in their

products.

RANs early campaigns focused on corporations that were involved in

resource use and extraction. Over the years, the organisation has expanded itsviews of how forest destruction plays out on a global scale. One extension of

this view is reflected in the Global Finance Campaign which targeted large

banks, including Citigroup and Bank of America, with the goal of getting them

to agree to environmentally responsible investment policy. The decision to

Environmental Politics 363

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

15/21

target private banks was a result of an analysis of threats to rainforests and

their inhabitants:

The impetus for the campaign . . . is the recognition that there are a multitude ofthreats that we now understand to rainforest ecosystems and their residentcommunities. Among them are mining, hydropower, oil exploration . . . So whenwe looked at the threats facing the rainforest, we came to one commondenominator, which was the capital investment necessary to fuel all these differentactivities . . . . also threaten the rainforest as a whole. (RAN 2004b)

A second extension of their view of how forest destruction plays out on a

global scale stems from their analysis of supply chains for forest products. In

reflecting on how supply chains function and how they affect environmental

quality, members honed in on the impact that climate change could have onforests worldwide. One of their major conclusions was that oil dependence is a

major driver of global warming and that this dependence is being fostered by

multinational corporations. Following this analysis, the organisation devel-

oped a campaign that pressured car companies to make vehicles with greater

fuel efficiency and that eliminated their greenhouse gas emissions.

In general, the perception of global problems stemming from business

practices has led RAN to situate its efforts within the anti-corporate stream of

global justice activism. The organisations focus on forest preservation crosses

over to the global justice movement by highlighting and working to reformwhat the organisation sees as the hegemonic power and undemocratic nature of

multinational corporations. The interrelationship of these domains of activism

was acknowledged by one activist who noted, economic interests cant be

considered without also considering the environmental and the social interests

(RAN 2004a). In targeting corporations, RAN often will develop a set of

requests or demands and make an initial attempt to work collaboratively. If

this does not work, then they may pursue direct forms of action to publicly

shame a corporation into altering its practices, either directly or by mobilising

local organisations and student groups. Whether in response to their initial

request or to subsequent actions, once a corporation agrees to change its

behaviour, RAN typically maintains a dialogue to ensure its commitments are

fulfilled. While collaborative tactics may appear reform-oriented, the

organisation consistently is critical of corporate power, uses diverse forms of

interaction to pursue its corporate agenda, and locates its global justice

activism in this domain.

Cognitive alignment and cross-movement activities

Over the years, environmental organisations have extended their work fromtraditional issues of pollution reduction and natural resource preservation to

areas associated with other movements including labour, peace, human rights,

and global justice (Rose 2000, Obach 2004, Rootes 2005). On the face of it, it

may appear that engaging in cross-movement activism is a deviation from an

364 J. Carmin and E. Bast

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

16/21

organisations focus. However, for the organisations in this study, extending

their work from the environmental to the global justice movement represented

a natural extension of deeply embedded patterns of activism that were rooted

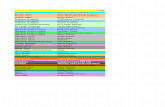

in their mission and values.The diagnoses that organisations make of environmental problems tend to

be rooted in their values and expressed in their discourse regarding the

appropriate relationship of humans to nature (Dalton 1994, Brulle 2000,

Dreiling and Wolf 2001). As summarised in Table 2, in each of the four NGOs,

interpretations of the source of environmental problems led to mission-related

assessments of the best means for addressing these problems. In particular,

FoE US and IR attributed environmental degradation to a faulty economic

development model while Greenpeace USA and RAN regarded corporate

hegemony and consolidated capital as the locus of environmental problems.Each organisation then advanced a prognosis that flowed from its diagnosis.

This prognosis determined the targets that the environmental NGOs engaged

in their ongoing environmental work; it also determined the global justice

targets and stream of global justice activism they pursued.

The relative emphasis an organisation places on social justice in its

diagnosis appears to be a pivotal factor in determining the specific stream of

global justice activism in which it participates. For instance, FoE and IR

maintain that the model of development being pushed by international

institutions the World Bank for both organisations, extending to tradeinstitutions and agreements for FoE violate human rights and harm the

environment. These institutions are not a primary source of pollution.

However, they are viewed as having policies and funding projects that promote

environmental degradation that, in turn, affect human rights and social justice.

For NGOs such as FoE and IR, social justice is an integral aspect of their

environmental critique and therefore serves as a driver for their targeting

international financial and trade institutions as well as providing them with a

rationale for linking their work to this domain of the global justice movement.

In contrast, Greenpeace and RAN focus on protecting the environment at

all costs. Since corporations are viewed as the driving force behind pollution

and environmental degradation, they are the primary global justice target for

these organisations. Greenpeace and RAN do consider social justice and equity

in their work but they tend to do so when it is associated with an ongoing

campaign rather than it being a catalyst for their activism in itself. For

example, in their forest campaigns, both organisations acknowledged the

impacts of multinational corporations on forest peoples as well as on the

environment. While staff members are concerned that corporate power affects

local peoples, their emphasis is on saving the forests by targeting corporations

initiating destruction. The perceived negative impacts of corporate power arecentral to the global justice movement. Consequently, given their efforts to

increase awareness of corporate practices and take action to improve corporate

responsibility, Greenpeace and RAN have situated themselves within this

stream of the movement.

Environmental Politics 365

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

17/21

Table2.

Globaljusticeframesandactivit

iesofenvironmentalNGOs.

Friendso

ftheEarth

US(FoE

US)

GreenpeaceUSA

Internatio

nal

Rivers(IR

)

Rainforest

Action

Network(RAN)

Diagnosisofsourceof

environmentalissues

Faultyeconomic

developmentmodel

Corporate

hegemony

andcon

solidatedcapital

Faultyeconomic

developmentmodel

Corporate

hegemony

andcon

solidated

capital

Prognosisinrelationto

globaljustic

eactivities

Addresse

nvironment

andsocialjustice

Stopcorpo

ratepollution

Addresse

nvironment

andsocialjustice

Changeco

rporate

practices

Primaryglobaljusticetarget(s)

Internatio

nalfinancial

institut

ions;trade

agreem

ents

Corporatio

ns

Internatio

nal

financialinstitutions

Corporatio

ns

Globaljustice

tactics

Policyrep

orts;lobbying;

media;

directaction

Directaction;media

Policyrep

orts;lobbying;

media;

directaction

Directaction;media;

localorganising

366 J. Carmin and E. Bast

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

18/21

Previous research suggests that structural differentiation (Zald and

McCarthy 1980, Staggenborg 1986, Hathaway and Meyer 1997) and cognitive

alignment (Arnold 1994, McCammon and Campbell 2002, Van Dyke 2003)

influence coalition membership, and by extension, cross-movement activismmore broadly. The potential to bring unique strengths and competencies to

alternative movements may be a relevant consideration when NGOs are

deciding whether to extend their existing work or develop new campaigns.

However, in each of the four cases examined, the ways the environmental

organisations engaged the global justice movement reflected a political critique

that was rooted in their deeply-held interpretation of the source of

environmental problems and the import placed on social justice as a means

for resolving these problems. In other words, these patterns suggest that

cognitive alignment, as reflected in diagnostic and prognostic frames,determines where within an alternative movement an organisation will situate

its efforts.

The presence of cognitive alignment demonstrates that NGOs tend to stay

true to their missions and values when engaging in cross-movement activism.

In an era when questions are being raised about the legitimacy and

accountability of environmental NGOs, this provides evidence that these

organisations are seeking to realise their societal mandate. This finding not

only has relevance to organisational legitimacy, but also to movement vitality.

It has been suggested that in order for the US environmental movement toachieve important gains, NGOs must expand their focus and relationships with

other organisations and movements (Shellenberger and Nordhaus 2004).

While, in theory, doing so could undermine the basis on which they are

empowered to act, the patterns in this study suggest that when environmental

NGOs extend their activism beyond their own movement, they are not

deviating from their goals or acting in ways that are antithetical to their

legitimate base of activity. Rather, cross-movement activism is a way in which

environmental NGOs work to realise their missions, enact their values, and

ensure that the movement remains relevant and energised.

Acknowledgements

We thank Deborah B. Balser for her input on the research protocols, Chris Rootes,Klitos Papastylianou and Stacy D. VanDeveer for comments on earlier drafts of thispaper, and the representatives from the environmental organisations who participatedin this study.

References

Arnold, G., 1994. Dilemmas of feminist coalitions: collective identity and strategiceffectiveness in the battered womens movement. In: M.M. Ferree and P.Y. Martin,eds. Feminist organizations: harvest of the new womens movement. Philadelphia:Temple University Press, 276290.

Benford, R.D. and Snow, David A., 2000. Framing processes and social movements: anoverview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 1139.

Environmental Politics 367

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

-

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

19/21

Bohlen, J., 2001. Making waves: the origin and future of Greenpeace. Montreal: BlackRose Books.

Brown, D.L. and Fox, Jonathan, 2001. Transnational civil society coalitions and theWorld Bank: lessons from project and policy influence campaigns. In: M. Edwardsand J. Gaventa, eds. Global citizen action. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Press,4358.

Brown, M. and May, J., 1991. The Greenpeace story. New York: Dorling Kindersley, Inc.Brulle, R.J., 2000. Agency, democracy, and nature: the U.S. environmental movement

from a critical theory perspective. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Carmin, J. and Balser, D.B., 2002. Selecting repertoires of action in environmental

movement organizations: an interpretive approach. Organization and Environment,15 (4), 365388.

Cohen, J. and Arato, A., 1992. Civil society and political theory. Cambridge, MA: MITPress.

Dalton, R.J., 1994. The green rainbow: environmental groups in Western Europe. NewHaven, CT: Yale University Press.

Della, Porta, D., 2005. Multiple belongings, tolerant identities, and the construction ofanother politics: between the European social forum and the local social fora. In:D. Della Porta and S. Tarrow, eds. Transnational movements and global activism.Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 175202.

Della, Porta, D., 2007. The global justice movement: an introduction. In: D. della Porta,ed. The global justice movement: cross-national and transnational perspectives.Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers, 128.

Doherty, B., 2006. Friends of the Earth International: negotiating a transnationalidentity. Environmental Politics, 15 (5), 860880.

Dreiling, M. and Wolf, B., 2001. Environmental movement organizations and political

strategy: tactical conflicts over NAFTA. Organization and Environment, 14 (1), 3454.Edwards, M. and Hulme, D., 1996. Beyond the magic bullet: NGO performance and

accountability in the post cold war world. West Hartford, CT: Kumarian Press.Edwards, M. and Hulme, D., 2003. NGO performance and accountability: introduction

and overview. In: M. Edwards and A. Fowler, eds. The Earthscan reader on NGOmanagement. London: Earthscan, 187204.

Friends of the Earth (FoE), 1992. Interview with FoE representative. 27 October,San Francisco, CA.

Friends of the Earth (FoE), 2004a. Interview with FoE representative. 2 March,Washington, DC.

Friends of the Earth (FoE), 2004b. Telephone interview with FoE representative. 18

March.Friends of the Earth (FoE), 2007a. Friends of the Earth US website. At http://

www.foe.org [Accessed 6 May 2007].Friends of the Earth (FoE), 2007b. Friends of the Earth International website. At http://

www.foei.org [Accessed 6 May 2007].Gerhards, J. and Rucht, D., 1992. Mesomobilization: organizing in two protest

campaigns in West Germany. American Journal of Sociology, 98, 555595.Greenpeace, 2000. Against the law: the G8 and the illegal timber trade. Amsterdam:

Greenpeace International.Greenpeace, 2001. In: Safe trade in the 21st century: the Doha edition Greenpeace

comprehensive proposals and recommendations for the 4th Ministerial Conference of

the World Trade Organisation. Amsterdam: Greenpeace International.Greenpeace, 2004a. Interview with Greenpeace representative. 2 February, Washington,

DC.Greenpeace, 2004b. Email correspondence with Greenpeace representative, received 10

March.

368 J. Carmin and E. Bast

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

http://www.foe.org/http://www.foe.org/http://www.foei.org/http://www.foei.org/http://www.foei.org/http://www.foei.org/http://www.foe.org/http://www.foe.org/ -

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

20/21

Greenpeace, 2007. Greenpeace USA website [online]. At http://www.greenpeaceusa.org[Accessed 9 May 2007].

Hathaway, W. and Meyer, D.S., 1997. Competition and cooperation in movementcoalitions: lobbying for peace in the 1980s. In: Thomas R. Rochon and David S.Meyer, eds. Coalitions and political movements: the lessons of the nuclear freeze.Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 6179.

International Rivers Network (IR), 2004a. Interview with IR representative. 13January, San Francisco, CA.

International Rivers Network (IR), 2004b. Telephone interview with IR representative.17 February.

International Rivers Network (IR), 2004c. IR website [online]. At http://www.irn.org[Accessed 9 May 2004].

Keane, and John, 1988. Democracy and civil society. London: Verso.Levitsky, S.R., 2007. Niche activism: constructing a unified movement identity in a

heterogeneous organizational field. Mobilization, 12 (3), 271286.McCammon, H., Campbell, J., and Karen, E., 2002. Allies on the road to victory:

coalition formation between the suffragists and the Womans Christian TemperanceUnion. Mobilization, 7 (3), 231251.

McCarthy, J.D., 2005. Velcro triangles: elite mobilization of local antidrug issuecoalitions. In: D.S. Meyer, V. Jenness, and H. Ingram, eds. Routing the opposition:social movements, public policy and democracy. Minneapolis, MN: University ofMinnesota Press, 87115.

McCarthy, J.D. and Zald, M.N., 1997. Resource mobilization and social movements:a partial theory. American Journal of Sociology, 82 (6), 12121241.

Motavalli, J., 1997. The Rainforest Action Networks founder targets big timber:interview with Randy Hayes. E Magazine [online], 8 (4), JulyAugust. Available

from: http://www.emagazine.com/oldissues/julyaugust_1997/0797conversations.html[Accessed on 17 October 2008].

Nordhaus, T. and Shellenberger, M., 2007. Break through: from the death ofenvironmentalism to the politics of possibility. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Oakes, J., 1980. Introduction. In: David R. Brower, ed. Environmental activist, publicist,and prophet. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Regional Oral History Office,The Bancroft Library.

Obach, B., 2004. Labor and the environmental movement: the quest for common ground.Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Oliver, P.E. and Johnston, H., 2000. What a good idea! Ideologies and frames in socialmovement research. Mobilization, 4 (1), 3754.

Rainforest Action Network (RAN), 2004a. Interview with RAN representative.12 January, San Francisco, CA.

Rainforest Action Network (RAN), 2004b. Interview with RAN representative.12 January, San Francisco, CA.

Rainforest Action Network (RAN), 2007. RAN website [online]. At http://www.ran.org[Accessed 7 May 2007].

Reese, E., 2005. Policy threats and social movement coalitions: Californias campaignto restore legal immigrants rights to welfare. In: D.S. Meyer, V. Jenness, and H.Ingram, eds. Routing the opposition: social movements, public policy and democracy.Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 259287.

Ring, E., 2000. A man for all Forests. EcoWorld: Nature and Technology in Harmony

[online]. 30 October. Available from: http://www.ecoworld.org/Home/Articles2.cfm?TID328 [Accessed 17 October 2008].

Rootes, C., 2005. A limited transnationalization? The British environmental movement.In: D. Della Porta and S. Tarrow, eds. Transnational movements and global activism.Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2143.

Environmental Politics 369

Downl

oad

ed

At:16

:1429

June2010

http://www.greenpeaceusa.org/http://www.irn.org/http://www.emagazine.com/oldissues/july-august_1997/0797conversations.htmlhttp://www.ran.org/http://www.ecoworld.org/home/Articles2.cfm?TID=328http://www.ecoworld.org/home/Articles2.cfm?TID=328http://www.ecoworld.org/home/Articles2.cfm?TID=328http://www.ecoworld.org/home/Articles2.cfm?TID=328http://www.ecoworld.org/home/Articles2.cfm?TID=328http://www.ecoworld.org/home/Articles2.cfm?TID=328http://www.ran.org/http://www.emagazine.com/oldissues/july-august_1997/0797conversations.htmlhttp://www.irn.org/http://www.greenpeaceusa.org/ -

8/8/2019 88013__911180898

21/21