026_MineSafe

-

Upload

tri-febriyani -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of 026_MineSafe

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

1/28

MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006 1

MineSafeWestern Australia

Long traditionof mine rescue .................page 6

Addressingwork–life balance .........page 23

Road safetyon mine sites

Vol. 15, No. 4December 2006

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

2/28

2 MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006

In this issue

An article by State Mining Engineer Martin Knee about what the term ‘safetyculture’ might mean for the mining industry leads this bumper final issue of

MineSafe for 2006.There are also reports on the formal activities that Resources Safety isengaged in, such as the Conference of Chief Inspectors of Mines and MiningIndustry Advisory Committee.

We have articles and pictorial spreads on the Underground Mine EmergencyResponse Competition, held recently in Kalgoorlie, and the Mines SafetyRoadshow 2006. Participants’ feedback on the Roadshow is included.

Working hours and work–life balance were important discussion topics duringthe Roadshow. In this issue, we present information on the recently releasedcode of practice and include a report on a talk by Professor Linda Duxbury, awork–life balance expert.

In response to requests for information, we have started a themed section

on road safety on mine sites. The aim is to alert readers to the availabilityof information and what is happening in this field, and generate discussiontopics, especially with the inclusion of selected summaries from ResourcesSafety’s incidents database.

We continue the series on the functions of other divisions in the Departmentof Consumer and Employment Protection with an overview of LabourRelations. To round out the series, Resources Safety will feature in the nextissue of MineSafe.

In the safety and health representatives section, we introduce you to DinoBusuladzic, who is based in Perth. We also cover some of the activities thathappened in Safe Work Australia Week. Readers are encouraged to check outthe Resources Safety website regularly to find out what’s new — updates andnew information are posted there first, including toolbox presentations from

the Roadshow.There is also news relating to dangerous goods safety and a review of a locallypublished paste and thickened tailings book that might interest readers.

Do you know if your ore contains heavy metals? In this issue we ask ‘What’sin your dust?’ and provide information on how to reduce exposure to toxicmetals.

We also report on some safety innovations and awards, as well as passingon safety alerts released by other organisations but relevant to the WesternAustralian scene. Specific safety advice is included in the significant incidentreport on a service truck tyre failure.

As 2006 draws to a close, I wish MineSafe readers and their families a safeand happy new year, and thank you for your interest and support throughout

the year.

Alan GoochActing Executive Director, Resources SafetyDepartment of Consumer and Employment Protection

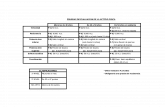

2. In this issue

3. Safety culture

4. Chiefs meet

4. Mine rescuers in real life scenarios

5. Diverse competitors travel distance to learn

6. Scenarios based on actual reports

6. Long tradition of mine rescue

7. Mount Charlotte tops

10. Road safety on mine sites Part 1

14. Mines Safety Roadshow 2006

16. About Labour Relations16. Bowler urges focus on workplace safety

17. Ask an inspector

18. Work Safety Award winners lead the way

18. Safe Work Australia Week a success

19. What’s in your dust?

20. Nick is a safe driver

20. Changes to Dangerous Goods Safety Act

21. Review of paste and thickened tailings guide

22. Working hours code of practice

23. Addressing work–life balance

24. MIAC’s first anniversary

25. Oil-filled circuit breaker failure

26. New technology for emergencyresponse monitoring

26. Training for new technologies

27. Significant incident report

28. What’s new on the web

© Department of Consumer and Employment Protection 2006

ISSN 1832-4762

MineSafe is published by the Resources Safety Division ofthe Department of Consumer and Employment Protection(DOCEP). It is distributed free of charge to employers,employees, safety and health representatives andmembers of the public.

Reproduction of material from MineSafe for widerdistribution is encouraged and may be carried out subjectto appropriate acknowledgement. Contact the editor forfurther information.

Mention of proprietary products does not implyendorsement by Resources Safety or DOCEP.

Comments and contributions from readers are welcome,but the editor reserves the right to publish only thoseitems that are considered to be constructive towardsmining safety and health. Reader contributions andcorrespondence should be addressed to:

Resources Safety, Locked Bag 14, Cloisters Square WA 6850

Editor: Susan HoEnquiries: (08) 9222 3573

Email: [email protected]: www.docep.wa.gov.au/ResourcesSafety

This publication is available on request in other formatsfor people with special needs.

List of contributors (from Resources Safety unless otherwise indicated):

Susan Ho Peter W Lewis Donna HuntMartin Knee Peter Drygala Peter O’LoughlinDenis Brown Lindy Nield Rhonda JogiaAnita Rudeforth Susan Barrera, Labour Relations Division, DOCEP

Robert Cooke, Paterson & Cooke Consulting Engineers, South Africa

Denis Brown was omitted from the list of contributors for the previousissue of MineSafe. We apologise for this oversight.

C o v e r i m a g e c o u r t s e s y o f K a l g o o r l i e M i n e r

( p h o t o : J o d i K i n g s t o n )

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

3/28

MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006 3

management and organisation factorsthat we now know contribute many ofthe causes of major accidents.

It is also critically important to recognisethat learning can occur not just withinthe mining industry, but also acrossindustrial sectors — such as aviation,

chemical or energy — precisely becausethe latent preconditions, rooted asthey are in organisational and humanbehaviour, are common to many sectors.

Learning also depends upon ourconception of the system. Although thephotograph of the donkey-cart mightappear humorous to us all — andvery far from the world of engineeringhazards — at a very general level thesystem failure that it represents can,and does, happen regularly, as depicted

by the aircraft in the other photograph.

We all talk about ‘safety culture’ fromtime to time, and it is one of the buzz-words that has crept into the discussionof safety in all industries. We often giveit a complex and pompous-soundingdefinition like:

‘The safety culture of an organisationis the product of individual and groupvalues, attitudes, competencies and

patterns of behaviour that determinethe commitment to, and the style and

proficiency of, an organisation’s healthand safety programmes. Organisationswith a positive safety culture arecharacterised by communicationsfounded on mutual trust, by shared

perceptions of the importance of safetyand by confidence in the efficacy of

preventive measures.’

A simpler and certainly a morehonest definition might be:

‘What people at all levels in anorganisation do and say when theircommitment to safety is not beingscrutinised’.

Organisations with good safetycultures commonly exhibit a ‘collectivemindfulness’ or ‘risk awareness’ — arealisation that they may be only aheartbeat away from a major accident.They are constantly, and at all levels,asking the question, ‘What is the worstthing that could happen here?’

Other organisations are less proactivein seeking out ways in which their safetymanagement systems might fail. Whilerisk awareness may seem intuitive,there may be in-built reasons why redflags or indicators of risk are ignored.

The first is the belief that ‘it can’thappen here’, based on conflictingtrusted, yet incorrect, information.Similarly, slowly building warning signscan be dismissed as just part of thenormal routine until, finally, somethinggives way catastrophically — or such

signs may appear only intermittently

and are simply out of sight, out of mind.

In other cases, there aremisunderstandings about exactly whatsignals a dangerous situation or whatmight be the cause. Even when warningsigns are detected, ’groupthink’,the pressure to make unanimousdecisions, can override doubt.

It is a common experience of the minesinspectorate that serious and majoraccidents can be traced to failuresin safety management systems, andinvestigations sometimes reveal thatthe systems in place are little morethan sets of manuals occupyingmetres of shelf space and bearing littlerelation to what actually goes on inthe workplace. They are ‘virtual’ safetymanagement systems — existing intheory but not in practice.

Critical issues for the industry,

particularly in the current climateof rapid expansion, staff mobilityand relative inexperience amongmany employees, are the loss ofcorporate knowledge coupled with andcompounded by the failure to learnfrom accidents and incidents — thismeans, in effect, that we have to learnthe same lessons over and over again.

The topic of learning from accidentsand incidents is a critically importantone for managers and engineers.Thirty years ago we commonly

attributed accidents and incidentssolely to ‘acts of God’, human error ortechnical malfunction. Those familiarwith the work of James Reason will beaware of his concept that an accidentwill only occur in a high-hazard systemif several of the in-built defences arebreached in succession. Near-misses,in particular, provide valuable learningopportunities, as they show how somebut not all of the defences can becomebreached in the future. However,accident analysis also has to take

account of the surrounding ‘latent’

Safety culture

From the State Mining Engineer

Varig cargo plane from Brazil parked at MexicoCity’s airport on 12 April 2006. Its cargo hadbeen unevenly distributed

‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.’ George Santayana, 1863–1952, The Life of Reason, 1905.

A P P

h o t o / E x e l s i o r — A

d r i a n R o g u e

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

4/28

4 MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006

The 48th Conference of ChiefInspectors of Mines was held inPerth on 8-9 November 2006.

The venue and chair for this annualconference rotate through therepresented States and Territoriesand observer countries Papua New

Guinea and New Zealand. Tasmania wasunable to host the conference this yeardue to the aftermath of the Beaconsfieldincident, so Western Australia steppedin at short notice, having last hostedthe conference in 2003.

The conference is important as it bringstogether the most senior technicalofficers with regulatory responsibilityand accountability for mining

Chiefs meetoperations in Australia to discussissues of common concern,including the National MinesSafety Framework.

Delegates also visited Alcoaof Australia’s Huntly mine andPinjarra Refinery.

Information on the functions ofthis group is available atwww.ga.gov.au/ccim

Left to right: Bill McKay (Cwlth), Simon Ridge (SA), Sue Kruze (Cwlth), Alan Gooch (WA), Kathy Harman (Cwlth), Mike Downs (Qld), JohnMitas (Vic), Martin Knee (WA), Clive Brown (WA), Rob Regan (NSW), Bill Taylor (NZ), Roger Billingham (Qld), Tim Gosling (NT), Rod Morrison(NSW), Kee Hah (NT), Greg Marshall (SA)

The 2006 Underground MineEmergency Response Competitionheld in Kalgoorlie in November sawthe Barrick Lawlers team scoop fiveawards, including best team.

This year’s competition venue was theimpressive KCGM Mount Charlotteoperation, which provided excellentconditions for the Barrick Lawlersteam, which also won the search andrescue, team skills, firefighting andteam safety awards.

The competition, the largest held in thesouthern hemisphere, even attracted ateam from Victoria, as well as 15 minerescue teams from across the State.

Mine rescuers in real life scenariosAccording to event organisers,The Chamber of Minerals andEnergy Western Australia, the eventis important in demonstrating theindustry’s commitment to safety andhealth across all Western Australianresource sites and locations.

Over some gruelling days before thecompetition weekend, teams workedup their fitness and skills to preparefor the backbreaking and intenseseries of scenarios they endured

over two days.With days starting at 4am to be on-siteready to go just after 5am, it can beexhausting just to watch.

Underground Mine Emergency Response Competition

S t o r i e s a n d s u r f a

c e p h o t o s b y P e t e r W L e w i s

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

5/28

MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006 5

But the competitors do their trainingand take the event very seriously — notonly professionally, but with dedicationand passion. Winning is great, butworking with mates and learningsomething new also inspires them.

Some of these ‘real-life’ scenarioswere based on actual seriousaccidents, with competitors having thebenefit of reading the incident reportsafter the event.

One such event was based on anincident that resulted in ResourcesSafety issuing Significant IncidentReport No. 78 Blasting Accidents.

wonderfully hosted by MC and localABC personality David Kennedy.

Guest speakers included EmploymentProtection Minister John Bowler andspecial guests Scott Franklin andJeremy Rowlings, from Stawell GoldMine, who gave a presentation on theirinvolvement with the blasting aspectsof the recovery efforts at Beaconsfieldearlier this year.

Ironically, the Beaconsfield rescue wasunfolding while the 2006 Surface MineRescue Competition was underwayin Kalgoorlie, and was in the back ofcompetitors’ minds at the time.

‘The fact that teams can leave thiscompetition with incident reports thatrelate to scenarios that they haveundertaken allows a lot of knowledgeto be gained,’ said competitioncommittee chairman Mark Pannewig.

Teams were put to the test withrealistic scenarios to evaluate theirknowledge and skills in fire fighting,first aid, search and rescue, roperescue, breathing apparatus skills,team skills and theory.

After two days of intense competition,all those involved prepared for agala presentation evening held atthe Miners’ Hall of Fame and again

There were all sorts of entrants at this

year’s Underground Emergency RescueCompetition, with one side travelling

from Victoria for the competition.

The Victorian competitors from

the Stalwell gold mine said they

enjoyed the opportunity to compete.

Spokesman Rob Stewart said the

competition here was twice as big as

those back home, and gave them an

opportunity to network and share skills.

‘We always learn something from the

WA guys, and we’ve been here training

in Kalgoorlie all week with Mick Nollas

from Riklan Emergency Service,’

Ron said.

Another team was made up of members

who met for the first time earlier in theweek, just before the competition, andwas led by team manager Lyn Van DenElzen. The Combined Kambalda MineRescue team consisted of six membersfrom five mines — Long Victor, Otter-Juan, Blair, Daisy Milano and Leviathan.

Captained by Jason Buswell, vicecaptain Barry Gresham, medic NickChernoff and Rick Broere, Jeremy Able,and Aaron Hendy, they commencedbonding and putting themselves

through some ‘gut wrenching’training after meeting.

‘This is a good experience for us and,since all the mines are within 30

Diverse competitors travel distance to learnminutes of each other, we are able to

help each other out and provide mutualaid,’ Lyn said.

‘This is giving us the confidence to workas a team, and this is great because wewouldn’t be able to compete as singlemines in this type of competition.’

But they were part of the spirit of thecompetition and came second in thenew team category and an impressiveeighth overall.

This year’s competition even attractedobservers from Argyle diamond minewho are planning to enter a team in the2007 competition, which is expected tobe even bigger.

The Combined Kambalda Mine Rescue team. Front left to right:Barry (Baz), Jason (Buzz), Jeremy (Jezza), Nick (Wild Man).Back: Aaron (Mad Dog), Rick, Lyn (Lynnie)The visiting team from Stawell, Victoria

Underground Mine Emergency Response Competition

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

6/28

6 MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006

The Chamber’s Nicole Roocke and DOCEP’sBrian Bradley and Peter O’Loughlin

Some of the ‘real-life’ scenariosin mine rescue competitions arebased on incidents that have beenthe subject of incident reports fromResources Safety.

This year’s first aid scenario wasbased on Significant Incident ReportNo. 78 Blasting Accidents, issued after

a series of three accidents in thespace of a few months in 1997.

The accidents resulted in one fatalityand two serious injuries, and allresulted from the injured beingtoo close to the face at the time ofdetonation.

The fatality and a serious injurywere caused by fly rock. In the thirdincident, the injured person washurled to the ground by concussionfrom the blast.

As the Resources Safety report pointsout, the cause of the death wasbecause the entry to a face, in which afuse had been lit, did not have a guardor warning notice and barricade toprevent access by personnel.

A second party of personnel enteredthe area to light the fuse, beingunaware that it had already been lit.

Scenarios based on actual reportsOn another occasion, a miner waslighting up 18 safety fuses individually.He had completed lighting thembut, before he could retreat to a safeposition, the first charge detonated.

Around the same period, a miner firinga longhole stope blast electrically witha shot exploder found he was unable

to initiate the detonator from the usualfiring position. He decided to resolvethis problem by moving closer to theblast area and shortening his firing line.

The competition scenario was extremelyrealistic, even to the extent that avehicle was partly covered in blastedrock and debris, while a pig’s headwas manipulated to demonstrate ashocking fatality. It demonstratedreal occurrences and represented achallenge to rescuers.

Resources Safety and The Chamberof Minerals and Energy WesternAustralia made a special presentationto invited guests Scott Franklin andJeremy Rowlings from Stawell Gold

Mine who were involved with therescue efforts at Beaconsfield earlierthis year.

The presentation of framed ancientcustoms of Occupation of the Minedriesin and upon the King Majesties Fforrestof Meyndeepe within His MajestiesCounty of Somsett, by then-Kalgoorlie

District Inspector of Mines PeterO’Loughlin, was well received.

Peter was also involved in thecompetition in an overall ChiefAdjudicator role, while Senior DistrictInspector of Mines Jim Boucaut wasan adjudicator in the new EmergencyResponse Coordinator’s event.

The competition was also attendedby the Department of Consumer andEmployment’s Director General,Brian Bradley.

The customs in the award date backto circa 1469, during the reign of KingEdward IV, and establish the strongtraditions of mine rescue.

Long tradition of mine rescueAn 18th century copy of the commonversion of the Mendip mining lawsshows the importance placed on life,and respect for miners, even in death:

‘That if any man by the meanes of thisdoubtful and dangerous occupacondoe by misfortune take his death as byfalling the earth upon him by drowningby stifleing wth fire or otherwise asin times past many have bene theworkmen of his occupacon are bound tofetch the body out of the earth and bringhim to Christian burial att theire owne

proper Costs and Charges althoughhee been threescore fathom under theearth as heretofore hath bene seene

And the Coroner or any other officer

att Jurye shall not have doe wth himnor them.’

It is a tradition that continues tothis day.

Underground Mine Emergency Response Competition

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

7/28

MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006 7

Mount Charlotte is probably one of thebest venues possible for undergroundmine rescue competitions.

Competition committee chairmanMark Pannewig said the still-operational mine offered a range ofoptions for the various scenarios thatare played out in exacting conditions,

and also had the benefit of beingclose to town.

‘It is the oldest underground mine inthe region and is unique in that it isone of the few existing mines that stillhas shaft access,’ Mark said.

The logistics behind the biggest eventof its type in the southern hemisphereinvolves hundreds — many behindthe scenes — with adjudicators, eventmanagers, committee organisers,‘casualties’ and assistants all playing

their part.Planning began in earnest monthsago with KCGM, owners of the mine,providing engineer Andrew Ross tohelp set up the event and staff whoput in much of the infrastructure forthe many scenarios.

Two of the events were held inan actual work area, effectivelysuspending mining, to add a real edgeto the competition.

‘It was one of the best we have run

— we are always trying to raise thebar and this year didn’t disappoint.We had a record 16 teams competing,where we normally have a maximumof 14, so putting an extra two teamsthrough all the events was a strategicchallenge,’ Mark said.

The committee began organisingthis event just after the surfacecompetition earlier in the year.

‘We have to bed down a site andfinalise the scenarios to ensureeverything is safe. As a fully self-funded event, we have to attractsponsors and put in the place the

logistics of the whole operation.’

The resources and costs of puttingon the events would be beyond whatindividual companies could afford oreven have access to. In fact, someof the teams were combined fromdifferent mines.

‘Considering most other competitionsare held on ovals with theinfrastructure built around them,it’s great that we can set them up ina real place on a real mine. Theseevents are paramount in trainingthese teams,’ Mark said.

Mark, who works as an undergroundoccupational health and safetytraining coordinator for Black SwanNickel Operation, has been involvedwith competitions for more than adecade, initially as a competitor, thenas an adjudicator before becominginvolved in the running of events.He was also chairman of this year’ssurface competition.

He said that occupational healthand safety was becoming far moreprofessional as an industry and ‘… lifeand limb are now more valued and theapproach is more professional and farmore legislated.’

Mount Charlotte tops

The Barrick Lawlers team took tophonours at the annual UndergroundMine Emergency Response Competition,winning the award for best team.

Barrick Kanowna was runner up, with

third place going to Oxiana Golden Grove.

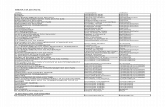

Awards

Team Skills:

Barrick Lawlers

Search and Rescue:

Barrick Lawlers

Fire Fighting:

Barrick Lawlers

Breathing Apparatus Skills:

Oxiana Golden Grove

Rope Rescue:

Barrick PlutonicTeam Safety:

Barrick Lawlers

First Aid:

Barrick Granny Smith

Overall First Aid:

Barrick Kanowna

Theory:

Oxiana Golden Grove

Individual Theory:

Mike Bowron (Oxiana Golden Grove)

Harry Steinhauser Award for

Excellence in Mine Rescue:

Rodney Goldsworthy

Emergency Coordinator:

Tim Campbell (Black Swan Nickel)

Best Scenario:

Fire Fighting and EmergencyCoordinator’s Events

Best New Captain:Ben Wither (Barrick Plutonic)

Best New Team:

Newmont Jundee

Best Captain:

Troy Johnson (Barrick Granny Smith)

Encouragement Award:

Mincor Operations

The top three new teams were Jundee,Kambalda and Cosmos.

Honour Board

Underground Mine Emergency Response Competition

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

8/28

8 MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006

Underground Mine Emergency Response Competition

P h o t o c o u r t s e s y o f K a l g o o r l i e M i n e r

( p h o t o : J o d i K i n g s t o n )

Competition chairman Mark Pannewig ready to start the firefighting event

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

9/28

MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006 9

Underground Mine Emergency Response Competition

P h o t o b y P e t e r W L e w i s

U n l e s s o t h e r w i s e

i n d i c a t e d , p h o t o s c o u r t s e s y o f M i k e L o v i t t

A w a r d p h o t o s c o u r t s e s y o f G o l d fi e l d s I m a g e W o r k s

Employment Protection Minister John Bowler presents Resources Safety’s Peter O’Loughlin with aframed picture in recognition of his 20 year service toGoldfields mines rescue. Peter is now based in Collie

Rod Goldsworthy (left), winner of the HarrySteinhauser Award, with Colin Steinhauser

Members of the Barrick Lawlers team with their Best Team Awards

Mick Nollas (left) of RiklanEmergency Management Systems,which sponsored the Best Captain Award won by Troy Johnson (right)of Barrick Granny Smith

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

10/28

10 MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006

Road safety on mine sites Part 1The introductory article by StateMining Engineer Martin Knee inthis issue of MineSafe is a timelyreminder of the importance ofa proactive ‘safety culture’. Inthe past few months, ResourcesSafety has received severalrequests for information aboutroad safety on mine sites. Somesafety and health officers areconcerned that, despite thebest intentions of most of the

workforce and the implementationof a variety of controls to addressroad safety issues, some peopleare ignoring workplace safety

requirements or forgetting hard-learned lessons.

Part 1 of this topic concentrates onfatigue and restraint use — two of thefour key behavioural issues associatedwith crashes (speed and alcoholare the other two). Future issues ofMineSafe will cover other factors thataffect road safety outcomes, including:

• road design and trafficengineering;

• road user behaviour;

• vehicle standards andmaintenance; and

• heavy vehicle dynamics.

The information presented isderived from a variety of sourcesbut is not exhaustive. Instead, thisthemed section aims to providediscussion points for workplacesto consider when identifying andassessing the hazards associatedwith vehicle movements ontheir site.

A selection of recent road safetyinnovations and past projects frommine sites around the world areincluded for interest.

A major cause of crashes and fatalitiesis fatigue. A search of ResourcesSafety’s incident database reveals a

variety of reports from the past tenyears indicating that the driver fellasleep. These include:

• Truck/mobile equipment collision— A truck driver fell asleep whiledriving his loaded truck towards thewaste dump. The truck veered offthe road and lodged in a windrow,damaging the steering rods.

• Truck/mobile equipment nototherwise classified — The driverof a dump truck received multiple

bruising to various parts of herbody and a fractured left thumbwhen the truck she was drivingwent up an embankment and thenback onto the haul road after she

fell asleep. She was not wearinga seat belt at the time and wasthrown around the cab.

• Truck/mobile equipment collision— A haul truck collided with thewindrow when the driver fellasleep while driving the truck out

of the pit.• Truck/mobile equipment not

otherwise classified — The driverof the contractor’s truck fellasleep while driving between theheadframe and the ROM stockpile.

Various statistics are available on therisks associated with lack of sleep.For example, going without sleep for 17hours apparently has the same effecton driving ability as a blood alcoholcontent (BAC) of 0.05%, and after 24

hours, the effect is equivalent to a BACof 0.10% (VicRoads Safer Driving Kit,2002, Fact Sheet 13: The Hazardsof Shiftwork, available from www.vicroads.vic.gov.au/saferdriving).

Driver fatigue Elsewhere (www.spinneypress.com.au/204_book_desc.html), it has beenestimated that the risk of a crash is fourtimes greater after missing a night ofsleep — the same as driving with a BACof 0.08%.

Particularly noteworthy for many mining

operations is the observation that shiftworkers face a greater risk than otherworkers because of driving when theywould normally be asleep, and gettinginsufficient or poor quality sleep.

Regardless of which statistics arequoted, the effects of fatigue on roadsafety are well known. In crashescaused by fatigue, the driver has eitherfallen asleep at the wheel or been soexhausted that he or she has madeserious or fatal driving errors. TheNOVA: Science in the News website(www.science.org.au/nova) has a wealthof information and related links underthe topic ‘Driver fatigue — an accidentwaiting to happen’.

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

11/28

MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006 11

Research started by a team at TheAustralian National University in 1997has led to the development of faceLAB,information and communicationstechnology (ICT) that can be used totrack the movement of a driver’s head,including head position and orientation,and which way the eyes are looking andblinking rate.

To commercialise the results, SeeingMachines Ltd (www.seeingmachines.com) was set up in 2000. In 2005,the company entered a research

collaboration agreement with NationalICT Australia (NICTA), which is

Australia’s ICT Centre of Excellence andreceives Australian Government andAustralian Research Council funding.The aim is to explore the use of ICT toreduce road accidents relating to driverfatigue by warning drivers before theybecome too drowsy.

The system was trialled successfullyin the United States earlier this year,when it was installed in trucks fora large oil field services and miningcompany, and it will soon be installedin trucks servicing oilfields in Canada.

Seeing Machines also has adevelopment agreement with an

Driver alert

In terms of managing fatigue at theworkplace, a recommended startingpoint is the Code of Practice — WorkingHours 2006, issued by the Commissionfor Occupational Safety and Health andits Mining Industry Advisory Committee.

The associated risk managementguidelines are a useful tool whenconsidering potential occupationalsafety and health hazard factors andrisks, such as fatigue, from workplaceworking hours arrangements.

A paper presented by Peter Simpson,of BSS Corporate Psychology Services,at the Mineral Drilling Associationof Australia’s Inaugural TechnicalSymposium: Promoting Safety andProfessionalism in Drilling, heldin October 2004, summarises amining case study on fatigue and its

management. It states that there areno simple solutions to the issues raisedin the study’s survey. Also, sleepingdisorders need to be considered inworkplace fatigue strategies.

Although there may be a role fortechnological solutions to fatigue insome situations, it is important thatemployees are given opportunities todevelop the attitudes and skills requiredto manage their own fatigue.

Some of the author’s recommendations

to improve management of these issueson site are:

• training supervisors to recogniseand appropriately manage fatiguedemployees — and extend training tosenior managers so they supportefforts to manage fatigue, including

employees’ and supervisors’willingness to self manage;

• educating at-risk employees toimprove their understanding ofhuman sleep physiology andfatigue, and increase theircapacity and willingness toprotect their fitness for work;

• providing training in sleep hygiene,particularly in relation to getting tosleep and staying asleep when onnight shift; and

• enabling isolated employees towork with or interact with others(e.g. relaxed radio rules betweenmidnight and 5am to allow driversto chat and conduct simple quizgames), as increased simulationbenefits alertness levels.

automotive industry supplier inGermany, with the aim of going into

serial production of driver monitoringsystems for heavy vehicles.

The work with the companies inGermany and North America led to therecent production release of the DriverState Sensor – Research (DSS-R), aresearch version of technology aimed atresearch organisations and fleet trials.

The product’s rugged design andfully automatic operations are saidto make it ideal for permanent andunsupervised installation in vehicles.The Australian mining industrywill no doubt keep an eye oncommercialisation of this product.

Road safety on mine sites Part 1

So how does the DSS-R work?The DSS-R finds the driver’s face,automatically generating a modelthat takes into account unique facialfeatures. This takes less than a second.

Once modelled, the DSS-R begins

real-time 3D head pose tracking andthe system will find and track eyelidclosure. This provides detection ofdriver attention and distraction.

All measurements are optimised so thatnatural head motion does not degrade headtracking performance.

For detecting fatigue, the DSS-R comes withtwo algorithms. One is a simple detection

of micro-sleep events characterised by thedriver closing the eyes for more than a pre-defined period. The second algorithm is awidely accepted standard called PERCLOS.

PERCLOS observes the eyelid closuresignal to establish a fatigue metric that

considers measurements taken overseveral minutes. Optional audio alarmscan be raised as a result of either ofthese metrics.

P h o t o s c o u r t e s y o f S e e i n g M a c h i n e s

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

12/28

12 MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006

In an ABC interview on 15 August 2006,Ian Cameron, Chief Executive Officerof the Office of Road Safety, indicatedthat Australians are forgetting theimportance of wearing seat belts,which is ironic given that Australia wasan international leader in introducingcompulsory seatbelt wearing 30 yearsago, saving many thousands of lives.

It has been reported (see www.spinneypress.com.au/204_book_desc.html) that the main cause of injury anddeath in a crash, at any speed, is whenthe driver and passenger are thrownaround in the vehicle. At 50 km/hr thisis like falling from the top of a three-storey building. A seatbelt prevents thisand greatly reduces the risk of injuryand death. It also prevents people beingthrown from the vehicle in a crash.

In the light of these observations, it

is interesting reading reports fromthe past decade in Resources Safety’sincident database that mention seatbelts in the summary. The incidentsinclude rollovers, loss of control anddriving over an edge.

Many of the reports indicate that, atthe time of the incident, the driver oroperator was wearing his or her seatbelt and was not injured. For example:

• Truck/mobile equipment overedge — A truck driver reversed his

dump truck up a windrow on an oredump. The bank gave way, resultingin the truck flipping over on its tray.

Fortunately, the truck driver waswearing a seat belt.

• Truck/mobile equipment rollover —An elevating scraper rolled onto itsside while returning to the pit fromthe feed preparation ore hopper.The operator was wearing his seatbelt and suffered no injuries.

In a few incidents, the person receivedminor injuries due to the seat belt, butthe consequences would probably havebeen more severe had a seat belt not

been worn. For example:• Truck/mobile equipment rollover

— The operator of a dump trucksustained bruising from the seatbelt when his vehicle toppledbackwards onto the ROM padfloor while dumping. The groundbeneath the back tyres of the truckcollapsed when the tray of thetruck was tipped.

• Light vehicle incident — A lightvehicle being driven around a

bend on the haul road slid on thewet road and rolled over when thedriver lost control of the vehicle.The driver was wearing a seat beltand only received a minor injury tohis shoulder.

In those incidents where the driveror operator was not wearing a seatbelt, the outcomes were usually not asfavourable. Some examples are:

• Truck/mobile equipment overedge — A truck driver received

lacerations to his scalp and arm;neck and back strain; and minorshock when his truck and trailer

Belt uprolled over the edge of the ROMstockpile. The side-tipping truckwas being unloaded when the tiphead area gave way. The truckcame to rest five metres belowthe head level. The driver was notwearing a seat belt.

• Truck/mobile equipment nototherwise classified — The driverof a dump truck received multiplebruising to various parts of herbody and a fractured left thumbwhen the truck she was drivingwent up an embankment andthen back onto the haul roadafter she fell asleep. She was notwearing a seat belt at the timeand was thrown around the cab.

• Light vehicle incident — A drillerfell out of a moving vehicleinjuring his head and shoulderwhen he attempted to close thecab door, which had opened asthe vehicle was going around acorner. As he grabbed the door,

it fell off its hinges pulling himout of the cab. He had not beenwearing a seat belt.

It is also clear that not only shouldseat belts be worn, but they needto be properly adjusted and fit-for-purpose. For example:

Truck/mobile equipment nototherwise classified — A truck driverreceived injuries to the head, neckand shoulders when travelling ona rough section of the road on the

surface waste dump. The tensionin the seat belt was insufficient torestrain the driver.

Road safety on mine sites Part 1

Visibility project

As reported in BHP Billiton’sSustainability Report 2006 (www.sustainability.bhpbilliton.com/2006/performance), the Six SigmaVisibility Project was a joint activitybetween the Mount Arthur Coal

operation in New South Walesand 3M, a diversified technologycompany. The impetus was thefinding that, in the majority of

near-miss incidents involving equipmentand vehicles at Mount Arthur, people hadreported not seeing the other vehicle.The aim was to increase the visibilityof equipment, vehicles and signs atthe mine. Twenty-two incidents wereanalysed — half occurred in the daylightand half were after dark.

Truck drivers involved in the incidentswere surveyed, revealing concerns aboutthe visibility of vehicles and signs onsite. A range of road signs and vehicle

markings was trialled. Driversfrom all crews were interviewed todetermine which performed bestin terms of improved visibility andsuitability for continued use.

New signage and vehicle markingshave been adopted as the sitestandard with the expectation that

the risk of vehicle collisions will begreatly reduced. The project hasalso enhanced operator attentionon road safety.

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

13/28

MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006 13

At the 2006 Queensland Road SafetyAwards held recently (see news sectionat www.racq.com.au), the Premier’sAward for Excellence in Road Safetywas presented for an awarenessinitiative designed to decrease fatigue-related motor vehicle crashes amongmine shift workers.

The recipient was a partnershipbetween the Mackay Road AccidentAction Group fatigue managementteam and the Mining Industry RoadSafety Alliance, who joined forces todevelop the initiative to inform mineshift workers in central Queenslandabout the dangers of driving while

tired. The program for mining worksites includes employee and contractoreducation presentations and othermaterial designed to maintainawareness on the hazards associatedwith driver fatigue.

The Mackay Road Accident ActionGroup comprises representatives

of the Queensland Police Service,Queensland Transport, Main Roads,local government, Queensland Fireand Rescue Service, QueenslandAmbulance and the Royal AutomobileClub of Queensland (RACQ).

The Mining Industry Road SafetyAlliance was formed in response to

Fatigue awareness program wins Queensland awardincreased traffic flows on highwaysand road systems resulting from theexpansion of mining activities in centralQueensland. Queensland miningcompanies operating out of the region,such as Anglo Coal Australia and BHPBilliton Mitsubishi Alliance (BMA), areworking with Queensland Transport

and the Queensland Police Service. Theaim is to address road safety initiativesto improve traffic flows and the safetyof road users, including improvedhighway infrastructure, bettercoordination of wide load movementsand education aimed specifically atthe mining industry.

Mine sites have particular issues withdelineating road edges after dark,especially on bends and curves. Thedelineating devices need to be robustand highly visible, given the propensityfor them to become dust collectors andthe need to be seen by both light andheavy vehicles, some with restrictedvision.

Solutions to assist driver judgementon roads in poor light conditionsinclude the use of wind-driven rotatingreflectors on roadside posts and

implementing regular wash-downs

of reflective devices.

There is now a new type of roaddelineator called ‘Dingo Eyes’,specifically designed to enhance visualguidance at night when traditionalmarker performance may be limited.Basically, Dingo Eyes are polesincorporating solar-powered LEDs,which shine continuously after darkor during inclement weather, andstandard reflective material. They canbe uni- or bi-directional and come in arange of colours. The bright LEDs arehighly effective at marking road edgesand getting the attention of drivers,increasing driver alertness andawareness of potential hazards.

See in the darkAccording to the Road and Mining

Supplies website (www.roadandmining.com.au), trials on winding public roadsin Norfolk, England, and Kwazulu-Natal Province, South Africa, were verysuccessful, with significant decreasesin recorded crashes.

Also, a Western Australian mine sitereported that Dingo Eyes resulted ina marked improvement for operatorson night shifts in sections of haulroads that were previously difficult todelineate effectively. The devices weresubsequently used on haul roads thatwere not thought to pose problems— the improvements were sufficientto make it worthwhile installing thedelineators elsewhere on site.

Road safety on mine sites Part 1

Contact us - Perth inspectors Mineral House, 100 Plain St, East Perth WA 6004Anil AtriSenior Inspector of Mines (Perth Region)

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 9222 3290Fax: 9325 2280

Denis BrownSenior Electrical Inspector

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 9222 3546Fax: 9325 2280

Dino BusuladzicSenior Mechanical Inspector

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 9222 3538Fax: 9325 2280

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

14/28

14 MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006

Mines Safety Roadshow 2006

In October 2006, Resources Safetytravelled from the Goldfields to thePilbara to the Southwest taking thesecond annual Mines Safety Roadshowto Kalgoorlie, Bunbury, Karratha,Newman, Tom Price, and Perth.

The Roadshow presented informationon recent legislative changes and

safety and health issues that affectthe minerals industry, including therecently released code of practice onworking hours.

Resources Safety staff, including theState Mining Engineer and inspectors,were joined by the WorkSafe WACommissioner (Nina Lyhne) andindustry and union representativeson the Mining Industry AdvisoryCommittee (Nicole Roocke andGary Wood, respectively).

The first event at Kalgoorlie wasopened by Employment ProtectionMinister, John Bowler, and the finalevent in Perth was opened by theDepartment’s Director General, BrianBradley.

There were over 450 registrants forthe full-day sessions, and over 50nominated to attend the afternoonsession only on the code of practice. Intotal, over 80 attended in Kalgoorlie,95 in Bunbury, 65 in Karratha, 50 inTom Price, 25 in Newman, and 200

in Perth. Participants representeda range of industry perspectives,including safety and healthrepresentatives, occupational healthand safety professionals, supervisorsand managers. About half the totalaudience were safety and healthrepresentatives, but the proportionvaried from at least 64% in Kalgoorlie,57% in Bunbury, 55% in Karratha, 48%in Tom Price, 61% in Newman to 35%in Perth.

Each Roadshow started at 9 am and

finished by 3 pm. Fifteen minutes wasallowed for morning tea and 45 minutesfor lunch. These times were shortenedas necessary to keep the program onschedule as much as possible.

The topics covered were:• Overview of duty of care

• Hot topic 1: Provision of personalprotective equipment to labour hireworkers

• Investigations

- Role of Resources Safetyinspectors

- Role of Safety and HealthRepresentatives

- Round-table discussions of

investigation scenarios• Hazard identification and reporting

- Importance of reportingaccident and incident data

- Approaches to hazardidentification

- Round-table discussion onreducing the risk of strains andsprains

- Hazards associated withmachinery and plant

- Round-table discussion on

reducing the risks associatedwith machinery

• Hot topic 2: Likely impact of theDangerous Goods Safety Act 2004on the mining industry

• Working hours code of practice

- Main features of code and howto use it

- Tripartite perspective of code

- Using risk managementguidelines to workshop working

hours scenarios• Access to Resources Safety

information.

Consistent themes of the Roadshowwere the importance of effectivecommunication and the role of safetyand health representatives.

About 55% of participants took up theoffer to complete a survey form at theend of the day’s sessions.

• Of those who responded, 83%

strongly agreed or agreed that theInvestigations session increasedtheir knowledge and understandingof occupation safety and healthissues in mining and exploration.

On the road againFor the Hazard identification andreporting session, it was 82%.Eighty-one per cent stronglyagreed or agreed that Hot topic 1 onthe provision of PPE for labour hireworkers increased their knowledgeand understanding, and for Hottopic 2 on the Dangerous Goodssafety legislation, the figure wasalmost 88%. Almost 93% stronglyagreed or agreed that the Workinghours code of practice sessionincreased their knowledge andunderstanding of working hours asan occupational safety and healthissue.

• About 87% of respondents stronglyagreed or agreed that the round-table discussions were useful.

• About 39% of respondents thoughtthat the ‘showbag’ of ResourcesSafety publications and otherresource material was excellent,and 57% said it was good, giving atotal of 96% well satisfied with thehandouts.

• About 96% of Kalgoorlieparticipants found the venue to besatisfactory, with a similar figurefor Bunbury. In Karratha andTom Price, the figure was 92%. InNewman, all respondents thoughtthe venue was satisfactory. InPerth, almost 93% were satisfiedwith the venue.

• Almost 70% said that theirexpectations were met, and 28%indicated that they were partially

met. Only one person wasn’t sure.• A common comment was a

request for employers, managersand supervisors to attend theRoadshow or safety and healthrepresentatives training, or both,so they become more aware ofwhat a representative can do andsupport their representatives andrecognise their importance inachieving good safety and healthoutcomes in the workplace.

• Participants also appreciatedthe opportunities for round-tablediscussions and to meet otherpeople in industry, as well as meetResources Safety representatives.

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

15/28

MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006 15

Mines Safety Roadshow 2006

Some people indicated a desire formore round-table discussions andexercises.

• One detailed comment includeda suggestion for safety andhealth representatives to invitesupervisors and general managersor alternates in an effort to educatethe higher management levels.The respondent indicated thatpeople must sit an exam to geta shift boss’s ticket in WesternAustralia, but asked at what time is

the occupational safety and healthinformation updated for thesepeople throughout their careerother than through their own safetyand health representatives.

• The programs presented in thefirst few venues identified timingconstraints that were addressed

in subsequent presentations. It isinteresting to note that differenttopics produced extended questiontimes at different venues, so timinghad to be flexible to accommodatethe varying needs of the audiences.

• Numerous topics were suggestedfor future Roadshows, MineSafearticles and other ResourcesSafety publications. These will beaddressed over the coming yearor so, and are broadly grouped asfollows:

- Legislative issues

- Standards

- What can go wrong

- Fatigue management andworking hours

- Role of safety and healthrepresentatives (SHRs)

- Information sources- Inspectorate notices

- Consultation andcommunication

- Safety practices

- Safety and health innovations

- Plant and machinery

- Drugs and alcohol

- Road safety

- Dangerous goods

- Specific safety topics such

as food in mining, confinedspaces, mining techniquesand ground control, workingalone, safety case andconstruction in mining

- Specific health topics such asbullying, asbestos, noise andheat stress.

Kalgoorlie

Kalgoorlie

Perth Tom Price Newman

Bunbury

Karratha

Bunbury

Karratha

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

16/28

16 MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006

Labour Relations is a division withinthe Department of Consumer andEmployment Protection. The majorfocus of the division is promoting fairer,safer and more productive workplaces.This is achieved by undertaking arange of activities such as:

• providing information and advicethrough the Wageline call centre;

• investigating alleged breaches ofState industrial relations laws;

• proposing changes to State

industrial relations legislation;• providing education services and

seminars;

• coordinating public sector labourrelations; and

• making submissions to theWestern Australian IndustrialRelations Commission and theAustralian Fair Pay Commissionin relation to award and minimumwage entitlements.

Work Choices, the federal legislationintroduced early in 2006, regulatesindustrial relations for constitutionalcorporations. State industrial relationslegislation continues to operate fornon-constitutional corporations. It isestimated that there are about 400,000employees still covered by the Statesystem. There are still, however, grey

areas in the definition of a constitutionalcorporation, and these will gradually bedetermined by legal processes.

Wageline provides employmentinformation to private sector employersand employees on employmentmatters. Some interesting facts:

• Wageline receives about 8,000calls each month.

• The majority of calls are clientswanting information on wages.

• Callers also enquire about issuessuch as apprenticeships andtraineeships, annual leave andsick leave, parental leave andhours of work and overtime.

• Wageline provides awardsummaries of the major Stateawards and these can beemailed, faxed or posted toclients on request.

The compliance area of LabourRelations investigates allegedbreaches of State laws, awards and

agreements. About 1,000 complaintsare investigated each year and about$1million in underpaid wages isrecovered. The division also investigatesalleged breaches of the children inemployment laws under the Childrenand Community Services Act 2004.

About Labour RelationsThis year the Government made changesto the minimum conditions of employmentin State industrial relations legislation.Amendments to the Long Service Act 1958enhanced long service leave provisions,and amendments to the MinimumConditions of Employment Act 1993dealt with reasonable hours of workand improved conditions for unpaidcarer’s leave and parental leave.

One of the major issues facingall businesses is staff shortages.Recognising that staff retention andattraction can be improved throughproviding flexible working arrangements,Labour Relations hosted the Work LifeBalance Conference in February 2006 andthe Linda Duxbury Seminar in November2006. Both events demonstrated theimperative for businesses to respondto work life issues to attract and retainskilled staff, and discussed practicalstrategies to achieve this end. Theseseminars were well attended by privateand public sector employers andemployees. Other education services

include employer and employeeseminars, individual consultancy servicesand award or agreement comparisons.

The telephone number for Wagelineis 1300 655 266 or you can visit theLabour Relations website atwww.docep.wa.gov.au

Employment Protection Minister JohnBowler used the National Safe WorkAustralia Week held in late October2006 to urge West Australians to focuson the importance of developing aculture of safety at work.

National Safe Work Australia Weekaimed to encourage people to updatetheir knowledge about workplace safetyand make their workplace as safe as

possible.

‘Workplace safety is not just aboutemployers and workers and the StateGovernment supports initiatives that

continuously promote safety as we strivefor fairer, safer and more productiveworkplaces,’ Mr Bowler said.

‘Workers and their families shouldnot have to experience the pain andsuffering due to work place injuries.Safety in the workplace must be thenumber one priority of industry andsmall business.’

As part of the National Safety at WorkWeek, information on the latest safetyinitiatives were shared during the WorkSafe 2006 Forum in Perth.

Bowler urgesfocus on workplace safety

The Minister said it was only by workingtogether, talking about safety and thenputting ideas into action that workplacescould reach their safety goals.

During Safe Work Australia Week, peoplenetworked and exchanged work safetyinformation, ideas and initiatives with awide range of industries and businesses.They were also able to learn from whatothers had put in place to reduce the

chance of injury in the workplace.‘Workplace safety is all about peoplelooking out for their mates,’Mr Bowler said.

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

17/28

MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006 17

Askan inspector

Safety and health representatives section

Mine managersshould ensurethey receivecomprehensivedetails of allrelevant safetyand healthinformationprovided by

designers,manufacturersand suppliers of

plant, according to mines inspectorDino Busuladzic.

Dino is the Senior MechanicalInspector and oversees the machinerysection of Resources Safetythroughout Western Australia.

‘There is a duty of care for suppliers,manufacturers, designers, importersand installers under the Mines Safetyand Inspection Act, and they shouldbe more proactive in warning aboutincorrect use of plant and providerelevant information on correctusage,’ Dino said.

‘In our regulations, manufacturers,suppliers et cetera must identifyall hazards and specify any knownproblems. When we investigateincidents we rely on feedbackfrom suppliers as well as the minemanager to determine the cause.’

He said as an inspector he would

like to see the mine manager sourcemore information from suppliers andthe sharing of knowledge with othermines when there are issues with thequality of products or problems.

‘While everybody is trying to savemoney, the costs of incidents can

be huge — a multiple of any moneysaved by shortcuts — and we areconcerned some suppliers aregetting away with inadequate safetystandards.’

Dino believes it is important formines to liaise with supplierseven for small incidents, and allinformation of this kind should beshared with other mines and safetyalerts issued.

He said while minor incidents were

more frequent, the attention usuallyonly focussed on the big incidents,and the small things were generallyignored.

‘The small things can lead tobigger incidents. By acting on smallincidents we can often prevent largerones, and that may involve bringingin the manufacturers at the earlystages of investigation for input.’

Dino has been in the industry formore than 15 years and holds a

Masters degree in MechanicalEngineering from The University ofWestern Australia. He has worked asa designer and site engineer, mainlyin the mining construction industry,working through Queensland, theNorthern Territory and WesternAustralia.

‘I think my industry experiencehas given me a good backgroundas an inspector, and I am aware ofthe problems faced in the different

stages of construction and thecommissioning of plant,’ he said.

‘Part of my role is to ensure all plantcomplies with Australian Standards,codes of practice and our regulationsso it can be operated safely andwithout incident.’

1 Small incidents canbecome big incidents, soinvestigate thoroughly andtry to get to the bottom ofthings so you understandthe nature of incidents andthe reasons they occur.

2 Try to share informationwith other mines, suppliersand manufacturers as thiscould prevent the sameincidents in other mines.It is better to learn fromothers’ experience, ratherthan your own.

3 For new equipment andplant, ensure adequatetraining of operators andalso people in management

— some equipment ispushed over the limits toincrease productivity andsometimes managersoverlook the safeoperational limits of plant.

4 Make sure equipment isused for the purpose forwhich it was designedand, if any changes aremade, ensure the originaldesigner or manufacturer is

consulted and their opinionconsidered.

5 Try to strictly follow allregulations to ensure youare operating on thesafe side.

Dino’s topsafety tips

Did youknow?

• In 2005-06, 973 safety and health representatives from the miningindustry received introductory training, out of 3,331 trained from allindustries — that’s over 29% of the total.

• At the beginning of December 2006, there were about 1,800 electedsafety and health representatives in the mining industry.

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

18/28

18 MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006

Ausclad Group of Companies, PW & CJBradford and Royal Perth Hospital – SirGeorge Bedbrook Spinal Unit are thewinners of the three award categoriesof the prestigious 2006 Work SafetyAwards WA.

The companies will now compete in thenational Safe Work Australia Awards.

Ausclad, category 1 winner for

best workplace safety and healthmanagement system, suppliesengineering solutions includingfabrication, construction andmaintenance services across arange of industries.

The company has an excellent safetymanagement system in place, resultingin a 39 per cent reduction in lost timeinjury and disease over the past year.

The Sir George Bedbrook Spinal Unitwon category 2 for the best solution

to an identified workplace safety orhealth issue.

Caring for patients with spinalinjuries, the unit was unable tocomply with the hospital’s no-liftpolicy when turning spinal patients,who were lifted vertically and turnedby four staff.

Management and staff developed the

Aeroplane Pillow, which allows twostaff to turn patients without lifting,significantly reducing the risk ofmanual handling injuries to staff.

Category 3 is for the best workplacesafety and health practices in smallbusiness, and was won by PW & CJBradford.

Peter Bradford is a farmer andvolunteer firefighter who recognisedthat lifting and positioning heavywater-filled hoses into water tanks

Work Safety Awardwinners leading the way

on vehicles was putting firefightersat risk of manual handling injuriesand exposing them to the hazards ofworking at height.

In response, he developed a standpipethat allows mobile tanks to be filledwith water from overhead, eliminatingboth the handling of heavy hoses andthe risks associated with working atheights.

WorkSafe WA Commissioner NinaLyhne said the three winners wereterrific examples of the manyexcellent workplace innovations andoccupational safety and health systemsbeing developed in Western Australia.

‘Awards such as these are all aboutencouraging best practice in safetyand health, and the three winners areleading the way by making a significantcontribution to reducing the injury tollin workplaces.’

Safe Work Australia Week a successThe Work Safe 2006 Forum held inOctober attracted more than 600delegates, largely occupational safetyand health representatives, whoattended to update their skills andknowledge and to network with otherswho share an interest in safety.

Delegates were told that in WesternAustralia, we are still averagingaround 19,000 injuries per year thatare serious enough for people to needtime off work.

On average, every 25 minutes aWestern Australian is injured atwork, and every 16 days on average aWestern Australian dies from injuriessustained while earning a living.

The forum was part of activities heldduring Safe Work Australia Week,which proved to be a great success,

with widespread participation aimedat raising awareness of occupationalsafety and health throughout thecommunity.

Minister for Employment Protection JohnBowler opened the forum and said thatworkplace safety was all about peoplelooking out for their mates.

WorkSafe WA Commissioner NinaLyhne made a presentation on WorkSafechallenges and choices — is what we are

doing working? , following an overview of thehistory of workplace safety by Commissionfor Occupational Safety and Health chairTony Cooke.

‘Terrific work has been done over the past18 years or so in WA to reduce the tragictoll of workplace illness and injury, andevents like Safe Work Australia Week canonly contribute to this and further reduceinjuries and illness,’ Ms Lyhne said.

Mr Cooke talked of changes since thepre-Robens days when the duty of carewas observed in the breach and it wascommon to sue for negligence rather thanpreventing the injury, to a modern cultureof behavioural change in workplace safety.

Delegates had a choice of twosessions from skilled practitioners inthe areas of PINS – What they are andhow they work, Bullying – developingstrategies and changing the workplaceculture, Work life balance and workinghours, OSH risk assessment, Incidentinvestigation – techniques and tips,

and Returning injured workers towork.

During the week, companieswere encouraged to undertakesafety-related activities in theirown workplaces. More than 70companies registered their SafeWork Australia Week activities onthe WorkSafe website.

They took part in activities suchas morning teas and breakfasts tomeet and greet safety and health

representatives, training sessionson safety issues, workplacecompetitions and e-mailing of safetytips to staff.

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

19/28

MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006 19

‘Hazardous substances’ is the termcurrently used to describe a varietyof materials that can damage ourhealth and well-being. This term isused by occupational safety and healthprofessionals to describe any of thefollowing agents:

• substances used directly in workactivities, like adhesives, solventsand cleaning agents;

• substances generated by workactivities, fumes from welding or

evolving from process reactions;

• biological agents including allmicro-organisms and their toxinsand allergens; and

• naturally occurring substances,especially dusts from ores likesilica and toxic metals such asmercury, arsenic and lead.

Some ores contain toxic metals thatare also referred to as ‘heavy metals’.The most common found in WesternAustralia are arsenic, lead, mercuryand vanadium.

Toxic metals cause a variety ofhealth effects. Exposure to highconcentrations can cause serioushealth effects immediately. However,delayed disease can occur in peoplewho have been exposed to low levelsfor a long time because the bodywill accumulate or store the metalfor extended periods, sometimes fordecades, in susceptible organs such askidneys, liver, nerve tissue and bones.

It is the duty of the employer to protectemployees from being exposed tohazardous substances includingtoxic metals. Therefore, whenever anoperator starts mining a new ore body,it is necessary to determine if toxicmetals are present in the ore. Thiscan easily be done by undertaking ananalysis of the ore using techniquessuch as inductively coupled plasma(ICP) analysis or vapour generation toquantify concentrations of all materialspresent in the ore. If the ore mineralogy

changes, repeat analysis may berequired.

Following identification, a riskassessment should then determine if

employees could potentially be exposedto any toxic metals in dust or fumes.For example, will any of the processesemployed at the site concentrate thearsenic, lead, mercury or vanadium?Commonly, very low concentrations ofheavy metals can concentrate in onepart of the refining process. If so, therisk assessment should determine whatopportunities there are for employees tocome into contact with dusts or vapoursbeing released. For example, willmercury vapour be generated following

roasting and refining of pyrite orescontaining gold and silver? Elementalmercury can also concentrate in goldelectrowinning circuits. Arsenic dustand fumes are commonly emitted fromrefining and smelting metals from orescontaining copper, lead and tin.

Best management practice forreducing exposure to toxic metalsincorporates a policy with functioningprocedures that ensure:

• no smoking or eating in exposure

risk areas;• specific washing and clothes

changing protocols before eatingor leaving site;

• on-site laundering to preventtaking the toxic metals home tothe family;

• regular airborne contaminant andexposure monitoring to measurerisk and efficiency of controls; and

• baseline and routine biologicalmonitoring followed up withspecific health surveillance basedon the real exposures.

More detail on managing toxic metalexposure is available from the NationalCode of Practice for the Control ofWorkplace Hazardous Substances.This document has recently beenreviewed for replacement by the DraftNational Code of Practice for the Controlof Workplace Hazardous Chemicals,which was released for publiccomment at the end of September

2006, and is available from theAustralian Safety and CompensationCouncil website at www.ascc.gov.au/ascc/AboutUs/PublicComment/OpenComment

What’s in your dust?

Mercury became infamous for itsrole in the so-called mad hatters’disease, where felt-workersused mercury to shape hats. Asthe name suggests, long-timeexposures to unsafe levels ofmercury cause disturbance of thenervous system. An early sign ismild tremors but health effects canprogress to severe and aggressivepersonality changes. It can alsocause kidney damage.

Most heavy metals can causediseases of the central nervoussystem and kidneys, but lead hasalso been known to cause anaemia,infertility in men and abnormalitiesin developing babies whenpregnant women are exposed.

P h o t o s c o u r t s e s y o f D a v e D y e t , w w w . d y e t . c o m / m i n e r a l

Cinnabar (mercury sulphide)ore from Nevada

Native mercury onrock from California

Galena (lead sulphide) — provenance not given

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

20/28

20 MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006

Nick is a safe driver

Nick Kramer, who works for CoogeeChemicals, is the 2006 DOCEPResources Safety Dangerous GoodsSafe Driver of the Year.

Nick has been in the industry forthe past 33 years and has clockedmore than 3.5 million kilometreswithout any significant accidents, agreat track record that has seen himtravel the length and breadth of this

huge state.

After training as a mechanic withVolvo, Nick started with GascoyneTraders on the tools before gettingbehind the wheel, and finallyheading to Kalgoorlie where hespent about 20 years.

Over the years he has worked forsuch companies as Brambles, Bells,Wesfarmers and Boral transportinga range of dangerous goods fromliquid cyanide, fertilisers and lime

to sulphuric, nitric and hydrochloricacid, caustic, ammonium nitrate andeven packaged explosives.

While Nick said he was honouredto receive the award, he said therewere thousands of guys out there

just as good.

‘I think to be successful in thisindustry you need to have a bit of

diesel in your blood, you have tolike the lifestyle, enjoy working longhours and be customer focussed,’he said.

He said these days he enjoyedtraining up the young fellows newto the industry and helping themalong.

‘You have to tell them that if theyhave any questions they have to ask,it’s the only way to learn.’

He said these days the industrytraining was more professional andthe laws were getting better.

In a coup for Coogee Chemicals,his colleague at the companyDennis Treasure was runner-up inthe Dangerous Goods Safe Drivercategory.

Nick recently received his awardin front of more than 200 people200 peoplewho attended the 2006 Western

Australian Road Transport IndustryAwards at the Parmelia Hilton inPerth.

Rewarding excellence in theWestern Australian road transportindustry, the awards recognise thepersonal achievement of individualsand promote best practice withinthe industry.

The event is organised by TransportForum, the state’s peak roadtransport industry for private freight

operators, formed in 2000 followinga merger between the RoadTransport Training Council and theWest Australian Road TransportAssociation. These organisationshave represented the requirementsof members for more than 75 years.

Transport Forum is affiliated withthe Australian Trucking Associationand is the Western Australianbranch of the Australian RoadTransport Industrial Organisation.

Transport Forum regularly consultswith community members, industryorganisations and governmentagencies.

Changes toDangerousGoods Safety ActOne of the ‘hot topics’ at the recentMines Safety Roadshow was asession by Resources Safety’s

Rhonda Jogia on what changes tothe Dangerous Goods Safety Act 2004

mean for the mining industry.Responses to the public

comment period will be placed onthe Resources Safety website early

in the new year, while it is expectedthat the proclamation of the new

dangerous goods legislation willoccur during the first half of 2007.

Current regulations hail back to the1960s and the legislative reforms

aim to incorporate national concernsabout security and terrorism.

The new legislation will see a shiftfrom telling people and businesses

what to do to a performance-basedrisk management approach for

dangerous goods safety.

Under the changes, responsibility

for managing dangerous goodssafety will rest with the risk

generator.

The new regulations willcover security risk substances(SRS), including some forms

of ammonium nitrate (as pernational guidelines), and a cradle-

to-grave approach to the import,manufacture, storage, transport,sale and use of explosives and

ammonium nitrate.

Legislative changes will resultin new security clearance

requirements for all explosives andSRS licence holders, introductionof a security card for all people

with unsupervised access toexplosives and SRS, new regulations

to cover major hazard facilitiesand provisions for explosivesmanagement plans and shotfiring

plans.Nick Kramer (at left) receives his award fromPeter Drygala, Director Dangerous GoodsSafety with Resources Safety

Dangerous goods safety news

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

21/28

MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006 21

The first edition of Paste andThickened Tailings — A Guide,published by the Australian Centrefor Geomechanics in 2002, played animportant role in helping academicsand practitioners establish commonterminology and understanding in thisrapidly advancing field.

Launched earlier this year, thesecond edition, edited by RJ Jewelland AB Fourie of the AustralianCentre for Geomechanics, includes

new chapters on slurry chemistryand reagents, and a substantiallyexpanded case studies chapter.

The following review of Paste andThickened Tailings – A Guide (SecondEdition) has been provided by DrRobert Cooke, a director of Paterson& Cooke Consulting Engineers PtyLtd, South Africa.

The revised publication comprisestwelve chapters, each written byinternationally recognised experts,covering all aspects of paste and

thickened tailings from preparationthrough to surface and undergrounddisposal and mine closure. Theeditors note that the guide is nota design manual. Rather, it isintended to provide guidance andadvice for professionals consideringimplementing a paste and thickenedtailings system.

The chapter on sustainability notesthat it is important to examine fulllife-cycle costs before selectinga tailings disposal system. Apartfrom reduced operating and closurecosts, paste and thickened tailingssystems may also offer non-monetarybenefits in terms of improved publicperception regarding environmentaland social issues. Increasingly,for many operations, production islimited by water availability.

A good appreciation of rheologicalconcepts is important inunderstanding the key processesrelated to paste and thickened tailings

systems — tailings dewatering,transport and disposal. The rheologychapter provides a detailed overviewof these concepts and includes thesuggestion that tailings disposal

systems be designed to meet therheology required for the selecteddisposal method.

The chapter on materialcharacterisation notes that sometailings properties change during thepreparation, transport and disposalprocesses — most significant of theseis the change in the tailings mixturerheology. Guidelines for relevantmeasurements for characterising thetailings for each of these processesare presented. The author warnsthat beach slope angles determinedfrom laboratory flume tests shouldbe treated with caution as there is noaccepted method yet for predictingdeposition slopes from laboratorytests. The chapter concludes with auseful checklist of material propertiesthat should be measured for thethickened tailings projects.

It may be the least accessible chapterin the guide, but the slurry chemistrychapter deals with issues that arecritical to implementing successfulsystems for tailings containing clayminerals. The authors describe howthe colloidal properties of the claysuspensions influence the tailingsrheology and behaviour duringsedimentation dewatering. It is likelythat future significant advances inpaste and thickened tailings willdepend on a proper understanding ofslurry chemistry.

The chapter on reagents providesan interesting history of the

development of flocculants andcoagulants. Dr Cooke notes thathe was pleased to finally learnthe difference between the termsflocculant and flocculent! Reagentsare a significant cost for many pasteand thickened tailings systems. Theauthors’ overview assists designersand operators to optimise reagentselection and dosage by providing agood understanding of flocculationand coagulation mechanisms andthe factors that affect reagentperformance.

The chapter on thickening andfiltration provides an excellentoverview of the thickener types andthe methodologies used for sizing

thickeners.They note thatsizing paste thickenersis largely based on experiencewith similar installations. The varioustypes of filters used to producepaste are described with the relativeadvantages and disadvantages ofeach type. Useful indicative costs areprovided for thickeners and filters.

The transport chapter discusses

the flow behaviour of paste andthickened tailings in pipelines. Therelative advantages and limitations ofcentrifugal and positive displacementpumps are reviewed, and the authornotes that life-cycle costs must beevaluated when selecting the pumptype. Transport of paste by truckand conveyor is discussed, althoughthese modes are not widely used forsurface tailings disposal. The chapterconcludes with a review of aspectsto consider when undertaking an

economic evaluation or comparison oftransport systems.

A balanced assessment of theadvantages and disadvantages ofsurface disposal of paste or thickenedtailings compared with conventionaltailings is presented in the aboveground disposal chapter. The authornotes that although the conceptof high density tailings disposaltechnology was first implementedover 30 years ago, the adoption ofthe technology for surface has been

slow. This is ascribed to the lackof reliable methods for producing

Review of paste and thickened tailings guide

Continued on page 22...

-

8/19/2019 026_MineSafe

22/28

22 MINESAFE Vol. 15, No. 4 — December 2006

and transporting tailings. With therecent advances in these areas, it is

expected that implementation rate ofpaste and thickened tailings systemswill accelerate. The chapter detailsconsiderations for design, operationand management.

The mine backfill chapter discussesthe interdependence of backfillcomposition, underground benefits andlegal compliance. This is illustratedby considering the benefits ofunderground paste disposal for basemetal, coal, gold and platinum mines.The author reviews undergroundrock mechanics requirements,environmental requirements andconsiderations for ensuring successfulpaste transport. Examples of twounderground paste disposal projects

are presented to illustrate theapplication of underground pastebackfill technology.