Hasegawa Hat a 94

Transcript of Hasegawa Hat a 94

-

8/12/2019 Hasegawa Hat a 94

1/4

NON-PHYSIOLOGICAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN MALE AND FEMALE SPEECH:EVIDENCE FROM THE DELAYED FO FALL PHENOMENON N JAPANESE

Yoko Hasegawa Kazrre HafaUniversity of California, Berkeley

Department of East Asian LanguagesBerkeley, CA 94720-2230, USA

ABSTRACTThere is a perceptual difference between male and

female speech in fbndamental frequency and, lesssignificantly, in formant frequencies. These characteristicsare physiologically determined to a great extent, and thusspeakers exert little control over these characteristics intheir normal utterances. The present study investigateswhether some characteristics of hndamental frequency arealso manipulated by speakers to make speech quality morefeminine. The results of our experiment show that thedelay of the FO fall that signals a lexical accent isassociated with femininity in Japanese.

I. INTRODUCTION1 1 Comparisons of Male and Female Speech

Because male speech and female speech are evidentlydifferent, people usually have no difficulties inidentification of a speaker's gender. On average, femalespeakers have higher fbndamental frequency (FO) [I] andhigher formant frequencies [Z] the former being moresignificantly different than the latter between male andfemale groups [3]. Male speakers typically use low FO,which is associated not only a large body size but alsocharacter traits such as aggressiveness, assertiveness, selfconfidence, and so forth [4]. By contrast, high FOsuggests that the speaker has a small body, is non-threatening, submissive, subordinate, and in need ofothers' cooperation and good will [4].

FO is certainly influenced by anatomical differencesbetween male and female speakers; however, it has alsobeen reported that observed FO differences are muchgreater than those that can be attributed to anatomy.Many researchers have pointed out that FO differences aremore of a social phenomenon, reflecting different socialnorms laid down for men and women [5-111. Societyassigns different social roles to men and women andexpects different behavioral patterns fiom each group;language simply reflects this social fact [5]. Americanfemales, for example, make great use of rising intonation[6], and, when using formal and polite register, Japanesefemale speakers use higher FO than female speakers ofother languages [lo, 111.

The frequent use of higher FO and rising intonation

Speech Technology LaboratoryPanasonic Technologies, Inc.

Santa Barbara, CA 93 105, USA

are non-physiological aspects of female speakers. In thisarticle, we present yet another gender difference observedin Japanese speakers; viz. Japanese female speakers tendto delay the FO peak that signals a lexical accent. Thisphenomenon is known s the del yed F O fall (oso-sagariin Japanese). which is explained in the next section.1.2 Delayed FO FallThe Tokyo dialect of Japanese is a prototypical pitch-accent language in which accent is realized solely by achange in pitch, not by a change in loudness or durationsuch s found in English. Phonologically, it is widelyassumed that the accented syllable in Japanese has a hightone. and the post-accent syllable a low tone; phonetically,the accentual hi h tone is realized by a higher FO value onthe accented syllable than on surrounding syllables [12].This accentual FO peak, however, frequently occurs on thepost-accent syllable, without listeners detecting anychange in accent placement. For example, in lnamidd'tears' (Noun) the lexical accent falls on the first syllablelnd, however, the actual FO peak may occur on thesecond syllable/mi/ nd yet /na/ is perceived as accented.This phenomenon, originally called oso-sagari (delayed FOfall), was first reported by Neustupnf 1131

Investigating the delayed FO fall phenomenon, Sugitodiscovered that the most significant acoustic correlate ofthe Japanese accent is a falling FO contour of the post-accent syllable, rather than the FO peak location; i.e.,native speakers of Japanese perceive an accent on asyllable when it is followed by a falling FO contour [14].n the lnamidd example above, if the post-accent syllable

lmil contains a FO fall, lnal is perceived as accented, evenif the FO peak occurs on /mi/Although its occurrence varies between speakers as

well as between words uttered by the same speaker,delayed FO falls are more fiequently observed in wordswith an accent in certain positions or segmentalenvironments. In Sugito's data, about 36 of 3-, 4-, 5-syllable words with the accent on the initial syllable haddelayed FO fall [14]. In Hasegawa and Hata, we reportedthat 37 of the words beginning with l(C)VmVl wereuttered with delayed FO fall [IS]. We also found in thesame experiment that the phenomenon occurs much more

-

8/12/2019 Hasegawa Hat a 94

2/4

frequently in female speakers' utterances than those ofmale speakers (38 vs. 5 of the time). Our subsequentexperiment confirmed the same tendency [16].

Based on our previous experiments, we havehypothesized that the delayed FO fall is associated withfemininity in Japanese. i.e.. it makes speech sound morefeminine. To test this hypothesis, we conducted aperceptual experiment using a synthetic voice. Subjectswere asked to evaluate femaleness for each pair ofsentences which was prepared with and without a delayedFO fall. The result has supported our hypothesis.

11 Experiment2 1 Materials

Using a MITalk-based system, we synthesized thefollowing sentences. Each sentence contains a targetword (shown in Italics), which has the lexical accent onthe first syllable.

B frrmari kore desu ne. 'You mean this, don't you?'C. kutagaitai. 'I have sore shoulders.'D. kcuiari omosiroi. 'It's fairly interesting.'

The FO contour of sentencesA, C, and D was a rise-fall shape with the starting FO at 230 Hz and ending atabout IS0 Hz. Sentence I contains a tag question, andthus had a slight rise at the end of the sentence. Theglobal FO peak always occurred within the target word.

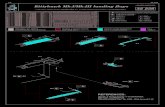

Each sentence had two variations: in one the targetword was made with a delayed FO fall @-token), and theother without it (ND-token). Figures and 2 representthe two types of FO contour within a target word.

In the D-tokens, the peak (300 Hz) occurred at 30msec into the second vowel, followed by a 7-semitone FOfall. Once the fall reached 200 Hz he FO was sustainedinto the third syllable. The ND-tokens had the peak (270Hz) in the middle of the vowel of the lexically-accentedfirst syllable, decreasing to 200 Hz at the onset of the thirdvowel.

Figure 1:FO contour of a target wordwith a delayed FO fall @-token)

imsec

Figure 2: FO contour of a target wordwithout a delayed FO fall (ND-token)

We have chosen two different peak frequencies forthe D- and ND-tokens in order to balance the perceivedoverall pitch ranges. Because the ND-tokens have moregradual FO change, if the peak 6equency were 300Hz, asis the case for the D-tokens, each N token as a wholewould sound much higher than the corresponding D-token. Comparing several ND-tokens with varying FOpe k fiequencies, we have determined that a 270-Hz peakrenders a voice range most compatible with the D-tokens.Other characteristics (e.g. formant frequencies, amplitude,speech rate) are identical in both types of tokens.

Having obtained eight distinct sentence-tokens (4sentences x 2 variations), we coupled the D-token andND-token of the identical sentence in two orders: 1) theD-token first and then the ND-token and (2) the NDtoken first and then the D-token, as shown below.

BE. D-ND B2. ND D fumuri kore desu ne.C1. D-ND C2. ND-D kalagaitai.Dl. D-ND D2. ND-D kmm omosiroi.

These eight pairs were duplicated and thenrandomized. We then added four red-herring pairs at thebeginning and recorded a total of 20 pairs. The generalinstructions of the experiment were given to the subjectsin written form as well as in spoken form using thesynthetic voice. This precaution was taken in order tofamiliarize the subjects with the synthetic voice quality.2 2 Procedure

32 subjects (19 males and 13 females, all nativespeakers of Japanese) participated in this experiment.They were told that one of the tokens in each pair wasuttered by a male speaker and the other by a femalespeaker, and that the.recorded voice was normalized withrespect to pitch and length. The subjects then listened tothe stimuli and decided which one sounded more female-like. In answer sheets they circled 1 if they thought thatwas likely to be uttered by a female speaker, and circled 2otherwise.

-

8/12/2019 Hasegawa Hat a 94

3/4

2 3 ResultsFigure 3 summarizes the results. The abscissa showshow many D-tokens each subject identified as uttered by afemale speaker, and the ordinate shows how manysubjects obtained the indicated score.

Dtd errsjudged s uttere byferFigure 3: Results of the experiment

There were 16 token-pairs, half of which had the D-N order and the other half the ND-D order. Therefore,if there is no perceptual difference between the D-tokensand ND-tokens, we expect the average of the subjects'judgments of D-tokens as m ore feminine to be close to 8(50 ). The result, however, shows that the responses areskewed: the average is 9.47 (59.19 ) with a standarddeviation of 2.2 1. The difference is highly statisticallysignificant (t (3 1) = 3.7526, two-tailed p 0.001). Thisresult was surprising because all subjects expressed, afterthe experiment, that they could not hear any differencebetween the two tokens in each pair, and that they circlednumbers randomly. The statistics, however, stronglysuggest that the difference was perceived, although thesubjects were not consciously aware of it.

It has been reported in the literature that not lllisteners utilize the same strategy in detecting FOprominence. Fo r example, among four cues for Englishaccent (FO. duration, amplitude, spectral patterns), FO isreported to be most significant [17], and yet, other cuesbeing equal, some listeners do not respond to FO changesalone in determining pitch peaks [18] Therefore, it isimportant to separate the subjects according to theirstrategies in FO-perception expe riments [19].As seen in Figure 3, there is a great variability in theresult of our experiment. One subject associated Dtokens with a female speaker 14 times out of 16. It isunlikely that the subject obtained this score by mere

guessing. We investigated how con sistent the subjects'responses were. Because each order of tokens wasduplicated, if subjects unconsciously perc eive d D-tok ensas more feminine, they would give the sameresponses for the identical pairs.For this purpose, we counted only thoseresponses, that indicated (A) the D-token morefeminine twice (consistent D-feminine responses) or(B) the ND-token more feminine twice (consistent

ND-feminine responses) for each identical pair ofstimuli. W e then divided (A) by the total consistentresponses (A B) and obtained the result shown inFigure 4.The average of consistent D-feminine responseswas 67 , the mode was 80 , and five of the 32subjects gave 100 consistent D-feminine responses.

On he other hand, one subject each delivered 0, 20,and 30 consistent D-feminine responses. W econclude, based on this result, that delayed O fall isa significant cu e to femininity in Japanese, bu t not allnative listeners are sensitive to it.

of consistent D - f e m a l eFigure 4: Consistent D-female Responses

III. DiscussionDelayed FO fall has been discussed in the literature forsome time to account for intonational meanings. Ladd,for example, proposes a binary feature [+/-delayed peak]for the relative temporal alignment of the H-tone and theaccented syUable [20]. If the H is late in the syllable, i.e.[+delayed peak], we get a rise; if it is early, [-delayedpeak], w e get a fall. H e claims that the difference betweenSwedish Accen ts 1 and 2, as well s he accentual patternsin Norwegian and Serbo-Croatian, can be representedwith this feature.Gussenhoven, who proposes the feature [delay] tooperate not only on falls but also on rises, claims that themodification delay has some intonational meaning: Thismanipulation is very non-routine, very significant' [21].He notes that delay in speech to children, where itgenerally occurs more frequently than in other types ofspeech, indicates the adult speaker's concern for beingunderstood by the inexperienced and possibly inattentivelanguage user. For example, when the sentence Wo uld

you rather have your Mummy take you to the hospital?' isaddressed to a sobbing child, the adult speaker may utterthe word ummy with a rise-fall c onto ur ([+delay]) ratherthan with an unmodified simple fall .These works have demonstrated that delay in thealignment between H-tones and accented syllables can besignificant in language; however, how this significanceactually signals mky differ according to language types.Because ll languages cited above can be categorized as

-

8/12/2019 Hasegawa Hat a 94

4/4

intonation languages [22], delays in the alignment of H- orL-tone and accented syllables are less restricted than thosein pitch-accent languages like Japanese. For example, theEnglish word rafher.which has the lexical prominence onthe first syllable, can be uttered with a noticeable FO peak(and a subsequent fall) on the second syllable. Thisdifference was exploited in British English until the earlytwentieth century to indicate an upper-class pronunciationof the exclamation meaning 'Yes, very much so' [21].

In Japanese, on the other hand, if the FO peak isdetected on the post-accent syllable. the perceived accentwill inevitably shift to that syllable, resulting in ananomalous pronunciation. Therefore, when the peak isdelayed, the fall rate after the peak must be significantlygreat to compensate for the delay. The later the peaklocation, the greater the fall rate required to maintain theaccentual pattern of the word [23]. Furthermore, themagnitude of delay has an absolute limit beyond which thedelayed FO fall phenomenon does not occur [23].

Based on the result of the present experiment, weconclude that the feature [delay] is a legitimate propertyof language, which can be exploited in language-specificways, and that in Japanese, this feature is used to expressfemininity.eferences

[I] Peterson, G. E., and Barney H. L. (1952).Control methods used in a study of the vowels, J.

Acoust. Soc. Am. 24, 175-184[2] Chiba, T., and Kajiyama, M. (1941). Zhe Vowel

Its Nature mid Structure (Kaiseikan, Tokyo).[3] Coleman, R. 0 . (1976). A comparison of the

contributions of two voice quality characteristics to theperception of maleness and femaleness in the voice, J.Speech Hear. Res. 19, 168-80.

[4] Ohala, J. J. (1983). Cross-language use of pitch:an ethnological view, Phonetica 40, 1-1 8.[5] Trudgill, P. (1974). Sociolinguistics: u

b~trod~tctionPenguin, Hannondsworth).[6] Brend, R M. (1975). Male-female intonation

patterns in American English, in Language and Sex:Drflerence and Dominance, edited by B. Thorne and N.Henley (Mewbiry, Rewley).

[7] Lakoff,R (1 975). Language avid Woman s Place(Harper Row, New York).

[ ] Brown, P., and Levinson, S. C. (1978).Polife~iess: Some Universals in Language Usage(Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge).

[9] Edelsky, C. (1979). Question intonation and sexroles, Lg. Sci. 8, 15-32.

[lo] Jugaku, A. (1979). Japanese Language andWometi (In Japanese) (Iwanami, Tokyo).

[ I I] Loveday, L. (1981). Pitch, politeness andsexual role: an exploratory investigation into the pitchcorrelates of English and Japanese politeness formulae,Lg. Speech 24,7 1-89.

[12] Pierrehumbert, J. B.. and Beckman, M . E.(1988). Japanese Tone Slnrclure (MIT, Cambridge, MA .[13] Neustupny, J. V. (1966). Is the Japanese accent

a pitch accent?, Onsei Gakkai Kaihoo 121 Reprinted inM. Tokugawa (1980). Akusenro (Yuuseido, Tokyo), 230-39.

[14] Sugito, M. (1968). Dootai sokutei ni yorunihongo akusento no kaimei, Gengo Kenkyuu 55.Reprinted in M. Sugito (1982). Nihotlgo ahserrto tiokenkyuu (Sanseidoo, Tokyo), 49-75.

[15] Hasegawa, Y., and Hata, K. (1988). Delayedpitch fall in Japanese, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. Suppl. 1.83,S29.

[I61 Hata, K. and Hasegawa, Y. (1992). A study ofFO reset in naturally-read utterances in Japanese, Proc.ICSLP, 1239-42.

[17] Fry, D. B. (1958). Experiments in theperception of stress, Lg. Speech 1, 126-52.

[I81 Hata, K. and Hasegawa, Y. (1991). The effectof FO fall rate on accent perception in English, Proc.Berkeley Linguistics Society, 12 1-29.

[19] Bartels, C. and Kingston, J. (1994). Salientpitch cues in the perception of contrastive focus, J.Acoust. SOC. 5,2973.

[20] Ladd, D. R (1983). Phonological features ofintonational peaks, Lg. 59,721-59.

[21] Gussenhoven,C. (1984). On the Grammar andSemantics ofSentence Accent (Foris, Dordrecht)[22] Cruttenden, A. (1986). Infonatioti (Cambridge

Univ. Press, Cambridge).[23] Hata, K., and Hasegawa, Y. (1988). Delayed

pitch fall in Japanese: a perceptual experiment, J. Acoust.SOC.Am. Suppl. 1.84, S156.