Dixit Etal 96

Transcript of Dixit Etal 96

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

1/27

The Determinants of Success of Special Interests in Redistributive Politics

Avinash Dixit; John Londregan

The Journal of Politics, Vol. 58, No. 4. (Nov., 1996), pp. 1132-1155.

Stable URL:

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-3816%28199611%2958%3A4%3C1132%3ATDOSOS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-S

The Journal of Politicsis currently published by Southern Political Science Association.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available athttp://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtainedprior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content inthe JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained athttp://www.jstor.org/journals/spsa.html.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printedpage of such transmission.

The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academicjournals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers,and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community takeadvantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

http://www.jstor.orgMon Jan 14 17:45:40 2008

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-3816%28199611%2958%3A4%3C1132%3ATDOSOS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Shttp://www.jstor.org/about/terms.htmlhttp://www.jstor.org/journals/spsa.htmlhttp://www.jstor.org/journals/spsa.htmlhttp://www.jstor.org/about/terms.htmlhttp://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-3816%28199611%2958%3A4%3C1132%3ATDOSOS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-S -

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

2/27

T h e Determinants o f Success o f Special Interestsi n Redistribu tive Politics

Avinash Dix itPrinceton University

John LondreganUn iversity of California, Los Angeles

We examine what d eterm ines whether an interest gr oup will receive favors in pork-barrel politics,using a model of majority voting with two competing parties. Each group's membership is heteroge-neous in its ideological affinity for the parties. Individuals face a trade-off between party affinity andtheir own transfer receipts.

T h e model is general enou gh to yield two often-discussed b ut com peting theories as special cases. Ifthe parties are equally effective in delivering transfers to any group, then the outcome of the processconf orm s to the swing voter theory: both partie s woo the grou ps that are politically central, and mos twilling to switch their votes in response to eco nomic favors. If groups have pa rty affinities, and eachparty is more effective in delivering favors to its own su pp ort group, then we can get the machine pol-itics outcome, w here each party favors its core su pp or t grou p. We derive these results theoretically,and illustrate their operation in particular examp les.

INTRODUCTIONE c o n o m i c redistribution occurs at two very distinct levels in the political pro-cess. T h e first kind is grand or progra mm atic redistribution. T h is reflects the pre-vailing ideological beliefs about equality and is carried out using income taxes(som etime s and in som e cou ntries wealth taxes) and the general social welfare sys-tem. These redistributive programs are relatively fixed for large periods of timeand change only when there is a major ideological shift in the population. In theUnited States, for example, a relatively egalitarian phase lasted from the 1930sthrough the 1970s and reversed only in the early 1980s. In the U nited Kingdo m, asimilar cen ter and m oderate-left consensus prevailed after World War I1 until theTh atch erite shift of 1979.

We are grateful to seminar audiences at Princeton, Cal Tech, UCLA, MIT, Harvard, Geneva,Georgetown and G eorg e Mason universities for their com men ts. We also express ou r thanks for finan-cial sup po rt: Dixit 's work was suppo rted by the National Science Founda tion and Londreg an's by aRichard A. Lester Prece ptorsh ip at Princeton University,

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

3/27

1133h e Determ inants of Success of Special Interestssecond kind of redistributio n, w hich m ight be called tactical, goes on con tin-

uously even while a given policy of grand redistributio n rema ins unchanged. T h istakes a variety of forms: subsidies or tariff protection to par ticu lar ind ustrie s, loca-tion of military bases and construction projects in particular districts, and otherschemes comm only labelled pork barrel. In the Un ited States, and elsewheretoo, such tactical redistribution is mu ch more the subject of everyday policymakingthan t he grand prog ram ma tic kind, and it is the main focus of our article.'

Previous theoretical research on such tactical redistribu tion has adopted on e oftwo comp eting models. T h is diversity in perspective is perhaps d ue to the hetero-geneity of redistributiv e politics itself. So me times, politicians appear to take careof their own ; consider the disprop ortiona te share of patronage benefits provideddurin g the first half of the twe ntieth centu ry by the Chicago political machine to itsloyal Irish supp orters (Rakove 1975). In other cases, loyal supp orters appear to betaken for granted, while redistributive benefits are targeted at groups of swingvoters. T h is form of redistribu tive politics recently became the target of com-plaints from New York De mo crats disappointed by th e sparse share of the particu-laristic benefits being channeled to the ir state, which had favored C linton by a wideelectoral margin in 1992, while the Clinto n White H ouse gives priority to the po-litical feeding and care of California, even though that state favored the presidentby a muc h narrower m argin; see Purd um (1994).

In this article we develop a more general framework that allows us to encom passboth considerations and d etermine when the one or the other w ill dominate. Wecon struct a model of political com petition in which two pa rties vie for voters' elec-toral upp port.^ Voters are heterogeneous in their affinities for the two parties. Inaddition, they care about particularistic benefits, and this interest tempers theirbasic party loyalties. The willingness of voters to compromise their party affinitiesin response to offers of particularistic benefits gives rise to red istributiv e politics inour m odel. Differences in the parties' abilities to deliver suc h benefits to differentgroups are w hat generate different outcomes.

If the parties are equal in their abilities to allocate redistributive benefits to allgroups, then the outcom e of tactical redistribution is governed by the different po-litical positions of the g roup s, and their d ifferent responses to the prom ises of eco-nomic benefits. Both parties favor groups of voters with relatively many politicalmoderates who are indifferent between the two parties and gro ups with rela-

tively high willingness to abandon their ideological preferences in exchange forparticularistic benefits, namely ex cludable con sum ption, in the fo rm of individualtransfers of income or in the fo rm of spen ding on projects which only benefit mem-bers of the target grou p. T h e result that b oth p arties may compete for the votes of

'T h e distinc tion between the two typ es of political processes is well recognized in the literature, butthere is no unanimously agreed terminology to express it. So me have called the ideological kind redis-trib utiv e politics, and the tactical or pork barrel kind distributiv e politics.

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

4/27

1134 Avinash Dixit and John Lon dreganthe same mo derate blocs of voters was noted by L indbeck and W eibull(1987), b utthey did not obtain all the implications of this case. We do so, and find some othe rattribu tes of voting gro ups tha t are conducive to th eir success in the game of tacti-cal redistribu tive politics.

In this settin g, largesse for some minor ity interes t groups enjoys bipartisan sup-port-both parties comp ete for the title of farmers' best friendn-while othe rgroups face equally dismal prospects for taxation in the postelection programs ofboth parties. Moreover, the net recipients of redistributive benefits need not con-stitute a majority of the electorate. In fact, the sheer num ber of members in a grouptur ns ou t not to affect the power of the gro up in the game of redis tributiv e politics.A very different pictur e emerges when the blocks of voters are identical in theirideological affinities for the partie s and in their willingness to sell their votes inexchange for particular istic benefits. In this settin g differences in th e parties' abil-ities to target redistrib utive benefits to different grou ps are the key determ inan ts ofthe outcomes. Such differences can arise when each party has its core groups ofconstituents whom it und erstands well. Th is greater understanding translates intogreater efficiency in the allocation of particu laristic benefits: p atronage dollars arespent more effectively, while taxes may impose less pain per dollar. Here ourdefinition of core con stitue nts resembles that used by Cox and M cCubb ins(1986). A party's core constituencies need not p refer its issue position. I t is theparty's advantage over its comp etitors at swaying voters in a group with offers ofparticularistic benefits that m akes the gro up core.

If parties are equ al in their abilities to levy taxes but are better able to spend pa-tronage benefits within core constituencies, the n we find the classic patte rn ofmach ine politics-parties favor their own core constituencies most, while target-ing taxes at grou ps of outsiders such as the core con stitue nts of the othe r party.T h is was the case analyzed by Cox and M cC ubb ins (1986). If partie s differ as wellin their abilities to levy taxes, the m atter becomes m ore co mp licated. If the taxingadvantage dominates, partie s may adopt a strategy of efficiently taxing their coreconstituents and using the proceeds to buy t he loyalties of more distant groups.We illustrate our model using some examples from U.S. pork barrel politicsduring the last century. In each case we examine how well the example meets theassumptions of our m odel, as well as how well it bears out the o utcome s predictedby the model. Protection of the garment industry offers a good example of theswing voter case, while many episodes from city govern ments of a cen tury ago

conform to the machine politics view.

The model developed here acknowledges three important factors at work in re-distributive politics. First, voters care about the redistribution to themselves of

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

5/27

1135h e De term inan ts of Success of Special Interestsmachine to a S und ay evening feast. Secondly, voters are attached to pa rties for rea-sons other than their own receipts from tactical econom ic redistribu tion. Fo r some,the reason is a strong attachm ent to a party's issue positions, including such mat-ters as interna tional diplomacy a nd defense, or the balance between citizen's rightsand the need s of law and order; for others there are personal loyalties to the partiesthemselves. We refer to all such attachm en ts to pa rties as ideological preferences oraffinities. T h ir d , redistribution plans mu st recognize resource con straints.

Som e models of political competition em phasize the redistributive q uestions inisolation, considering how a pie is likely to be divided under majority rule (e.g.,Shepsle and Weingast 1981). O the r mod els emphasize primarily the position-issueaspect of political c om pe tition (e.g., Do wn s 1957). An oth er strain of analysis, ofwhich this a rticle is a part, c onsiders individuals who care both about redistribu-tion a nd position issues. For example, a person w ith strong views on abortion willweigh these when comparing offers of redistributive benefits from competingcandidates.

For a political moderate, relatively indifferent between the political programs ofthe parties, differences in redistributive policies become decisive in the voting de-cision. In co ntrast, individuals with strong a ttachm ents to th e parties' issue posi-tion s will be very reluctant to trade the ir votes for redistrib utiv e benefits. As Riker(1982) put it, these people want to apply putatively universal values to all. Thismeans enforcing their religious affiliations or beliefs about legal abortion on all ofsociety, includ ing nonbelievers. To live und er policies that contra dict these val-ues is m uch worse than to lose in the market (204). For strong political adher-ents, losing means being emotionally deeply deprived (206).

In our stylized model of political competition, parties (and their candidates)draw o n personal loyalties and take issue positions in ways that change slowly overtime. We focus on interparty competition over tactical redistribution, holding is-sue positions as fixed for a given election cam paign. T h is is realistic. For exam ple,it has taken a generation for the De mo cratic party in the southe rn Un ited States tocomp lete the shift of its issue positions on civil rights. O n th e other hand, there isconsiderable flexibility in making cam paign prom ises regarding tactical redistribu-tion of private benefits. Politicians can raise a tariff here, subsidize the price of acrop there, and channel money for highway construction almost anywhere. Thu s,in our model, redistributive benefits may be thou ght of as soft money : the super-collider pro ject in solidly Rep ublican Texas sudden ly lost federal fun din g if not sci-entific me rit when the Clinto n ad min istration took office, while resources quicklymoved to the Fu sion P roject at Liverm ore La bs in the swing state of California.

Wh ile politicians can relocate redistributive p rivate con sum ption benefits fromone set of recipients to another, and do so relatively quickly, they are subject toan overall resource constraint. For many state governments whose constitutionscontain balanced budget provisions the budget constraint is obvious. For other

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

6/27

1136 Avinash Dixit and John Lon dreganborrow from those who believe they will subsequently be repaid. H owev er, taxpay-ers are not infinitely rich nor potential lend ers infinitely credu lous, so even govern-ments w ithou t explicit balanced b udget p rovisions are still bou nd by resource con-straints. We keep the d etermina tion of the resource constraints in the backgroundand take as given the sum that is available for tactical redistribution. Others in-cluding Cox and Mc Cub bins (1986) and Lindb eck and W eibull(1987) have studiedtactical redistribution under budget constraints; we will discuss their models ingreater d etail below.

My erson (1993) has examined th e incentives for candidates or pa rties to favor asubset of the voters at the e xpense of the rest. In his model, all voters are identicalto start with and do not have any ideological affinities. All that matters to them isthe tax they pay or the transfer they receive. Correspondingly, all that matters toparties is the size of their electoral coalition. They can gather the right amount ofsupport by picking voters at random and targeting the chosen ones for benefits.But in reality, tactical redistrib ution does not proceed by such ran dom selection ofbeneficiary g roup s of the right size. Th e electorate consists of identifiable distinctgroups, some of whom receive benefits because th eir g roup characteristics are con-ducive to success in the political game, while others lose because their groups areless well placed. Our model focuses on such differences and helps us understandwhy certain groups come to be favored. In this respect we modify, generalize, andenrich Myerson s analysis.We are thus asking how sho rt-run political com petitio n will take place in a set-tin g in which par ties issue positio ns are relatively fixed and tactical reallocationsof the budge t are relatively flexible. We ask what d eterm ines the recipients successin this process.

We consider electoral competitio n between two parties, labelled left L and rightR for mnem onic convenience. T h e two can differ from each other in their issue po-sitions (ideology) and their tactical redistributive promises to the voters. Recallthat we are assuming th e parties ideologies to be fixed within th e time-ho rizon ofinterest. Promises of tactical redistributive benefits are very much a matter ofchoice and t he focus of our analysis.

The voters are numerous and distinguished by the degree of their ideologicalaffinity to one p arty or the other.3 We model th e voters as a con tinu um distributedalong the real num bers ; a voter located at has an ideological preference forparty R over party L The voters also care for economic material benefits, mea-sured by consumption C Finally, the voting population consists of G identifiablegroups, distinguished by their occupation, geo graphic location, or some such char-

We have no better solution than does anyone else to the q uestion of why people vote at all when they

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

7/27

1137h e Determ inants of Success of Special Interestsacteristic. People within each group are heterogeneous in their ideological affini-ties, and the groups differ in their willingness to compromise the political prefer-ences in retur n for economic benefits. M ost importantly, the parties' redistributivepolicies can link taxes and transfers to th e mem bers hip of one of these groups; forexample, each farmer or senior citizen can be promised so many dollars. We willlabel the groups by the s ubscript i ranging from 1 to G. We denote by Q (C ,) theutility of a member of group i with consumption C,, and assume that U, is an in-creasing and strictly concave function, that is, the marginal utility of consumptionU 1,(C ,) s decreasing.Sup pose a memb er of group i, with the ideological preference X for part y R, willenjoy consum ption C IL f party L wins and implem ents its promised policies, andlikewise C I R rom part y R. T h en we assume that this voter will vote for party L ifhis or her extra utility of con sum ption from L's victory exceeds his or her ideologi-cal preference for R, that is,

Define the critical value or cutpoint X for grou p by

T h en all the mem bers of group i with values ofX less than X , will vote for part y L,and all the rest for party R. We den ote by a, . he cum ulative frequency distribu-tion of members of group i over the range of X, so the proportion to the left of X iis If the total num ber of voters in group i is N ,, then the num ber from thisgroup voting for party L will be N, @,(X,).Ad ding over gro ups, the total vote VLfor party L is then given by

Similarly, the n um bers voting for party R are

Within each identifiable group, individual voters vary in their affinities for thepolitical parties. We find Millian conservatives among the poor and socialistsam ong th e rich. How ever, th e distribution of political preferences is likely to dif-fer systematically across groups. We allow for these differences by letting thewhole functional form of the distribution a, . epend on i Of course it is per-missible for these distributions to be identical for two or more groups; that is a

Som e readers may prefer to interp ret this as Hotelling-type spatial model. T h e ideological prefer-

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

8/27

38 Avinash Dixit an d John Londre ganspecial case of our analysis. The possible differences of ideological affinity distri-butio ns across group s will have importa nt implications for the outcom e of politicalredistribution.

We will often find it useful to derive detailed results and interpret them bychoosing a special form for the utility function:

where E 0. T h e n th e marginal utility of an extra dollar of consum ption is

As C increased from 0 toward the marginal utility falls from toward 0 A onepercent increase in causes an E percent fall in the marginal utility. If party Lpromises to deliver an extra dollar to each member of gro up i it will shift the cut-point in its favor by

T h e great merit of this form of the utility func tion is that it lets us capture the vot-ers' trade-offs between political ideology and economic benefit in terms of twosimple parameters. We now explain this.

T h e E parameter captures the degree of diminishing returns to private con-sum ption. N ote that a dollar of extra consum ption sh ifts a group's cu tpoint by anamo unt equal to the m arginal utility of consum ption of each of its mem bers. If E issmall, marginal utility of consumption falls slowly as the level of consumptionrises. Therefore values of E near zero imply that even wealthy individuals remainvery sensitive to offers of income red istribu tion. For large values of E the willing-ness to compromise one's party affinities for more private consumption benefitsfalls rapidly with increased income. Thus, with large E, the parties can attract thevotes of the poor relatively more easily by offering them small economic benefits.We use the same E for all gro ups because differences only serve to make the nota-tion m ore complex withou t changing the basic intuition.

T h e parameter K measures the relative importance of consumption as againstthe ideological position, and here possible differences across groups do make animporta nt difference to th e analysis. A higher K mean s that an ex tra dollar of con-sumption offered to group i shifts its cutpoint by a greater magnitude. In otherwords, grou p i is more respo nsive to promises of econom ic benefits. Th u s , we maythink of K as mea suring how apolitical (or greedy) the voters of a grou p are. Anexample will show the nature of this effect. Newiy arrived immigrants in a south-ern state may care little wheth er th e con federate flag flies over the sta te universityand so may be relatively willing to vote for the candidate prom ising more g eneroussubsidies for their industry regardless of his or her position on the flag question.T h e low salience for the imm igrant of the issue position on th e flag corresponds toa high value of K . However, a long-time resident of the state, whose grandfather

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

9/27

1139h e Dete rm inan ts of Success of Special Interestscandidate offers no redistributive subsidies. This differing depth of political con-viction is represented in the model by differences in values of across groups.

It remains to specify how the parties' policies translate into consumptionbenefits or losses for different grou ps. We suppose that the incom es of workers inthe absence of any redis tribu tive policies are exogenous to our analysis and write Yfor the income of each member of group before any tactical redistribution. Th us ,we are leaving out of the analysis the possibility that the taxes and transfers usedfor red istribu tion also have efficiency effects on the economy, for example by dis-tor ting resource allocation and lowering the aggregate national prod uct. B ut we doallow some effects of this kind in an indire ct man ner as indicated below. Also, weare leaving grand or programmatic redistribution in the background, so the Yshould be t ho ug ht of as the result after any general income taxes, positive or nega-tive, have been levied.

Let (TiL; 1 ,2 , G ) denote the transfers promised by party L to each mem-ber of the different identifiable group s of voters, a nd similarly let T I R ) be the cor-respondin g transfers offered by pa rty R . As noted in the introduc tion, som e par-ties' issue positions, such as the Democrats' stand on programmatic incomeredistribution to the poor, have substantial budgetary implications, but we areleaving these in the background , and taking the amoun t available for tactical redis-tribution as given. Theref ore larger subsidies to some voting blocks mu st be bal-anced by smaller subsidies or larger taxes levied on oth ers. Wr iting B for th e avail-able b ~ d g e t , ~e have the budge t constr aint that res tricts the policies of each party:

GN Tik for k L , R.

i =

We allow the transfers to occur via a leaky bucket-of the Tkdollars offered byparty k to each member of group i, only a fraction may get through. Moreover, thefraction may depend on the identity of the group and the party; this captures thepossibility that each party has some core supp ort groups it understands bette r,and it can deliver benefits to them with greater efficacy. Lett ing tik denote the con-sumpti on benefit the grou p members actually receive, we write

where oi which we assume lies between 0 and 1, is the fraction lost during trans-port in the leaky bucket. In the machine politics model, if group i is a core groupfor party k, it will be able to target the benefits more effectively and ik willbe small. In the swing voter model, benefits are determined by the political pro-cess but delivered by an impersonal bureaucracy, so the identity of the party isimmaterial.

There is also a possibility of leakage in raising taxes, and it can in principledepend o n the relationship between group and party. Th us , a party may be able to

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

10/27

1140 Avinash D ixit and John Lond reganextract revenues from it s core su pp or t group m ore efficiently because the surveil-lance needed to attain compliance is easier given the com mun ity connection. T h e nthe party may persuade its core support groups to make sacrifices for politicalgain-pay mo re taxes so the proceeds can be used for purs uit of votes of othe rgroups in ord er to attain o r retain power. In this case we can write

H e r e y t k , which we assume to be positive, is the excess cost of raising a dollar oftax. It will be sm aller if i is a core sup por t group of party k. We regard this case asrelatively unlikely; core supporters will not long tolerate a party that deliversbenefits to o utsid ers. B ut we will inclu de so me analysis of thi s case for sake of logi-cal comp leteness.T h e consumption promised by party k to each member of group i is

Le t us recapitulate the struct ure of the model. Giv en the parties' tax and trans-fer strategies, the consu mptio n q uantities im plied for the various groups are deter-mined by equations a), (9), and (10). These in turn fix the groups' voting cut-points according to equa tion ( l) , and therefore their votes for the two p arties as inequation s (2) and 3 ) .We assume that each party seeks to maximize its vote. T h e parties' com petitionfor votes is a constant-sum game, and we look for its Na sh equilibrium , namely aconfiguration of strategies such th at neither part y can do bette r by unilaterally d e-

viating from it.

T h e intuition behind th e working of the model can be developed very simply byconsidering what one pa rty gains or loses by making a small margina l change in itstransfer policies. We do this usin g a simple diagram an d relegate th e formal alge-braic analysis of the equilibrium to th e app endix.Consider part y L's decision of whether to offer a little mo re to one gro up, say 1,at the expense of offering a little less to an othe r, say group 2 T hi s is illustrated infigure 1. T h e variable on the horizontal axis (in both t he top and the botto m halvesof the figure) is the e xten t of ideological preference X for party R. T h e upper halfshows the population density N (X ) of voters in g roup 1 at X ; similarly thelower half shows the densi ty N2+2( X) the for g roup 2. Initially, suppose the par-ties' strategies are such that th e cut-point X for group 1 is at point P shown in theupper half of the figure; similarly the cutpoint X2for grou p 2 is at P2in the lowerhalf. T h e density of population of group 1 at P is the height PI D 1; his equals NlC ~(X~).imilarly P2D 2 N2+2 (X 2) for group 2.6

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

11/27

I

ttachment to Party

ttachment to Party

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

12/27

1142 Avinash Dixit and John L ondreg anNow suppo se party L dec ides to spend a small incremental sum , say 1, on eachmember of group 1. Because the fraction O L leaks, each member actually receives

only (1 OIL ) ollars. T hi s causes some group-1 individuals who were close to thecutpoint shift their votes to party L ; this shifts the cu tpoint X to the right. T h emagnitude of the shift is found using equation (6); it equals the extra consum ptionmultiplied by the marginal utility ofco nsu mp tion , namely (1 OIL )K I (CIL)-E Inthe figure the new cut-point is at Q 1 .Writing E l for the point on the density curvevertically above Q the num ber of voters who switch to party as a result of theinducem ent is the area PlD l E I Q 1 . Since the increment in consum ption is small,the width PIQ is also small, so the area can be well approximated by the produc tof the height PID l and the width PIQ namely

To obtain the N 1 dollars spent on group 1, party L must raise (1 y z L )N 1 ol-lars from group 2. For this, it must tax each member of group 2 an amount(1 y2L)N1/N2.T ha t shifts groups 2's cutpoint X 2 from P2 to Q2 as somegroup-2 individuals close to the previous cutpoint abandon their s upp ort of partyL. By calculation similar to that above, we see that the length of P2Q2s (N1 N2)(1 -y2L)~ 2(C2L) -E ,nd the loss of group-2 votes to party L is

Th is is the area P2D2E 2 Q 2 n the lower half of figure 1.Comparing the two formulas and canceling the common factor N1, we see thatparty L will find the small shift of policy toward grou p 1 and away from grou p 2 toits advantage if

We can learn mu ch abou t the party's incentives to allocate its redis tribu tive favorsacross groups by examining the various term s in this expression.First, a higher K I in relation to K~ is conducive to gro up 1 being favored overgrou p 2. A group that is less attached to its political ideology and is more ready toswitch its votes in response to prom ises of economic benefits is treated more favor-ably. Moreover, this consideration applies to both parties, so we expect such a re-sponsive grou p to be pursued by both partie s and therefore do particularly well asa result of the parties' political c ompetitio n.Second, a higher 1(X1) relative to 2(X2 ) is conducive to grou p 1 being fa-vored over group 2. A group whose voters are relatively numerous at the cutpointgets favorable treatment. T h is is because more of its members switch their votes inresponse to a marginal improvement in the promised benefit. Once again this cal-

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

13/27

1143h e Determ inants of Success of Special InterestsIf the two pa rties have equal abilities to give benefits,or collect taxes from each

group, then in equ ilibrium the cutpoint will be at the center of the ideology spec-trum, namely X X2 0; the appendix offers a formal proof. Th en the grou psthat are densely represented at the center will be beneficiaries of redistributivepolitics. Groups that are numerous but concentrated at large positive (or largenegative) values o f X will not partake in th is benefit: they w ill be w ritten off by oneparty an d taken for granted by th e other.

T h ir d , if is low relative to G then for equal transfers C1 is low relative to C 2,and m arginal utility of consum ption is higher for group 1. Th eref ore its cutpointshifts by more p er dollar of favors. Th is ten ds to favor group 1 in the politicalgame. T h e effect is stron ger th e larger is E and the effect is again equally present inboth parties' calculations. Thus, other things equal, we should expect the poor todo well in tactical redistrib utive politics. H owev er, the reason is not that any ethi-cal considerations ente r the parties' calculations. Instead, it is a cold calculation ofvotes-the poor voters switch more readily in response to econom ic benefits be-cause the incremental dollar matters m ore to them .

Fou rth, the total population sizes of the two gro ups, N l and N 2 completely can-cel out of the calculation. T h e reason is that to give a dollar to each member of thesmaller gro up, it is necessary to tax each memb er of the larger gro up by less than adollar, an d therefore its cutpoint shifts by a smaller magnitude. T h e effect on thetotal votes gained or lost at the margin then does not depend on the group size. Infigure 1, a change in group size causes proportional and offsetting changes in thevertical and the horizontal dim ensions of the areas D E Q i Of course a change inthe num bers of a group, holding the out put per capita constant, changes the totalnational product and hence the consu mp tion am ounts that all voters receive. T hi seff'ect emerges in t he appe ndix, w hen we de term ine th e full equilibrium.

In the appe ndix we also derive a formula that combines all these parameters toprovide a quantitative m easure of the power of each grou p to attract tactical re-distributive favors; see equation (17) there.

Finally, the leaky bucket effects are specific to a party-group pair. Wh en partyL is bette r able to target its benefits to grou p 1, that is, when is small, pa rty L ismore likely to favor group 1. T hi s conform s to the core sup por t group view.However, if party L is less able to raise taxes from its noncore group 2, so Y ~ Lslarge, it is less likely to favor gro up 1. T hi s goes against the core s up po rt groupview; the pa rty mig ht even be driven to tax its core sltpporters to buy the votes ofother groups and get into power. But as we said above, we regard this outcome asunlikely, at least over any appreciable leng th of tim e.

Of course all these inferences are based on the examination of just one party'sincentive to alter its policy at the margin; given the policy of the other party.Formal proof that the same results also hold in the equilibrium, when each partychooses its strategy as a best response to the other's strategy, can be found in the

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

14/27

Avinash Dixit and John Lond regan

We now offer some examples to illustrate an d elucidate the analytical results inthe preceding section.The Swing Voter Outcome

If the political parties are approximately equal in their abilities to redistributebenefits once in office, as might be expected to be the case if policies are adminis-tered by an impersonal civil service bureaucracy, our model implies that they willtend to pursue symmetrical strategies. In this setting we saw that the followingtypes of groups will have an advantage in redistributive politics: (i) groups withrelatively many moderates whose relative indifference between the ideologicalprograms of the two parties can be resolved by offers of redistributive benefits,(ii) groups that are relatively indifferent to party ideology relative to private con-sumption benefits, (iii) low-income groups whose marginal utility of income ishigher, making them more willing to compromise their political preferences foradditional private consumption.She er num bers are relatively unim portan t. As the size of a group falls, so doesthe cost of buy ing an additional percentage point of vote share amo ng its mem bers.In a way we made m ore precise in the p revious section , these two offsetting effectsof grou p size approximately cancel in equ ilibrium.O ur m odel's p rediction th at groups containing relatively m any political moder-ates will receive largesse is consistent w ith the unflagging gene rosity of the C linto nadm inistr ation toward California. As a swing state in presiden tial politics Cali-fornia contains relatively ma ny voters near the threshold of indifference betweenClinton an d his potential Rep ublican challengers. In ad dition to reb uilding schoolsand freeways, disaster relief for California is geared toward refurbishing the win-ning vote m argin C linton received in California in the 1992 election.

T h e result is also consistent with t he favorable treatm ent received by senior citi-zens who are basically a cross-section of the whole population and therefore arewell-represented near the political cente r of the population, a nd the unfavorabletreatm ent received by urba n minorities who are clearly in the dom ain of one partyand not likely to switch to the o ther.Ga rm ent workers are another interesting case in point. T he ir low incomes makethem potentially attrac tive targets for redistributive benefits from b oth p arties. Ittakes more political will power for a member of the ga rmen t worker's unionearning less than $10 per hour to resist offers of largesse from an anti-unionRepublican candidate than it does for a high paid member of the airline pilots'association.G arm en t workers had a second trait identified by o ur analysis as impo rtan t in re-

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

15/27

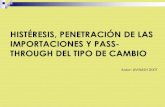

1145h e De terminants of Success of Special InterestsCe nsus of M anu facture s closest to that year, namely 1982. We com pare the sh are ofapparel workers living in a state, with the degree to which the state was up forgrabs electorally. While the 1.189 million workers who toiled in the apparel indus-try in 1982 accounted for less than 2% of the labor force, they app ear to have beenconcentrated in what were then electorally pivotal states.Le tting p measure the fraction of the population of U.S . garm ent workers whowere in a pa rticu lar state, say North Caro lina, we can calculate the state's log-oddsratio as

ln(p) ln(1 p) .T h is is the log of the o dds th at a randomly chosen apparel worker lived in th e state.T h e higher the probability, the larger the log odd s ratio. Le t m denote the absolutevalue of the state's marg in for Reagan versus Carter:

m = Votes cast for Reagan I 1Votes for Reagan plus Votes for Car ter 2Smaller values of m thus denote states in which the 1980 election was closest. Asimple plot of 1against m (see figure 2) reveals the tende ncy for to be small when1is large-all bu t two of the states with above-average values of 1had closer-than-average margins. A statistical test confirms this: the X test for independence re-jects the hypothesis that the observed association between above average concen-trations of textile workers and below average electoral margins is random. Underthe null hypothesis the X statistic has 1 degree of freedom , indica ting a 5% criti-cal value of 3.84. The realized value for the statistic is 5.63, well in excess of thisthreshold.O ur theory tells us that the pivotal location would ten d to make apparel workersrecipients of bipa rtisan redistribu tion. Shifting voters in states with close marginswill magnify th e effects of any redis tribu tive strategy.

These two attributes, low income and political centrality, offer an explanationfor the garment industry's history of receiving tariff protection with bipartisansupport. The first Multi-Fiber Arrangement, exempting textiles from many ofthe provisions of G A T T was negotiated d uring the Republican adm inistration ofRichard Nixon at a cost per job saved of $22,000 d urin g 1974 alone (Hufbau er,Berliner, an d Elliott 1986). T h e second M ulti-Fiber Arran gem ent was reacheddurin g the De moc ratic administration of Jimmy Carter, and it again provided forspecial protection from imp orted garm ents at a cost per job saved of $36,000 dur-ing 1981 alone (Hufba uer, Be rliner, and Elliott 1986). Reagan, who is noted for thesuspicion with which he viewed any Carter initiative, nevertheless went on to ne-gotiate the third Multi-Fiber Arrangement and to reach bilateral restraint agree-me nts covering textiles and apparel with mo re than 30 countries, creating over 600

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

16/27

Avinash Dixit and John Londreg an

SD-7 18547,189394 56.0284M a r g i n f o r R ea ga n o v e r C a r t e r

Baldwin (1985) in his regression analysis of the Tokyo round of trade negotia-tions noted that an industry's size was not significant as a predictor of whether itreceives tariff protection. Our analysis has a natural explanation for this finding:group size cancels out in calculating the gains and losses of votes per dollartransferred. When a small group gets additional redistributive benefits, these aredivided among a small number of individuals, shifting the group's cutpoint sub-stantially. T h e same total transfer, if made instead to a large group , would am oun tto less per capita, and m ove the cu tpoint of that gro up by less. T h e total num ber ofvotes shifted is the same in the two cases.Th e Core Support Outcome

Examples from urban machine politics illustrate the forces pushing politicalcompetitors toward asymmetrical strategies. During the nineteenth and earlytwen tieth cen tury urban political machines channeled benefits to core con-stituencies that rou tinely favored them at the polls by wide margins. T h e machinesappeared to rely on re distributive private benefits rather than issue positions to at-tract voters. The prototypical machine supporter if polled about his views on thefree silver controversy would be likely to agree with Richard Croker's famous re-mark: What's the use of discussin' what's the best kind of money? I'm in favor ofall kinds of money-the more the better. (Riordan 1963, 88). A machine politi-

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

17/27

1147h e Determ inants of Success of Special Intereststhe Philippines, as no platform seems to be comp lete witho ut them bu t heregarded particularistic benefits as the key to winning elections (Riordan 1963,88-89).T h e key to the electoral strategies of the u rban political mach ines was the ir abil-ity to provide personal services to their core con stituents at lower cost than couldtheir competitors. They did this by knowing their constituents. In New York,Tammany ward leader George Washington Plunkitt (Riordan 1963,25-28,90-98)kept track of constituents' likes and dislikes, compulsively participating in a spec-trum of social events. He attended baptisms and bar mitzvahs, weddings and fu-nerals, baseball games and dances, and always stood ready to ingratiate himself.Ch ildren knew Plun kitt as Uncle George, a name he soug ht to make synony-mo us with candy (Riordan 1963, 28). Tammany boss Charles Francis Murphywould hold regular daily meetings with constituen ts: Each n ight after nine o'clockhe would station himself by a lamppost ou tside the Anawanda Clu b and hear whatanyone wished to tell him (Allen 199 3,20 9).

The second way services flowed from the machine came in the form of an un-written insurance contract. George Plunkitt sought to be among the first at thescene of a fire in his dis trict, following the so und of fire eng ines to the sight of theblaze and finding hotel accommo dations, clothes, and food for those who had beenburned out until they could find new apartments. He was routinely roused in themiddle of the nigh t to bail ou t loyal con stituents arrested for infractions of the law.He would appear in court to arrange for legal counsel for one constituent threat-ened with eviction or to pay the rent of another. He found jobs for unemployedloyalists and restored them for those who had been fired (with cause) from m unic-ipal employm ent (R iordan 1963, 90-93). By being in touch with his constituencyhe was able to provide a very narrowly targeted form of social insurance.

In co ntrast, no nmach ine politicians were at a marked disadvantage. Lacking thewell-developed sup po rt networks they were unable to target red istributive benefitsto supp orters with th e accuracy and effectiveness of the m achine. In colorful lan-guage Plunkitt describes the failure of reform candidates to distribute patronagebenefits once in office, and notes their fundamental informational disadvantage(Riordan 1963, 18-19, 57-60). De spite the rhetorical appeal of a campa ign forclean government, nonmachine candidates were handicapped by their inability tocomp ete with the m achine at the redistribu tion of patronage benefits.

We conten d that the advantage enjoyed by the m achines arose because they werebetter able to spend within their core than the nonmachine politicians. If this ad-vantage is what stood b ehind the use of asymm etrical redistributive strategies, weshould expect the redistributive strategies used in interne ine contests betweenpoliticians of the same machine to be more symmetrical, and show behavior thatconforms to the swing voter mod el. Inde ed they do. Consider the primary con-test for leadership of New York's Second District between Patrick Diver and

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

18/27

48 Avinash Dixit and John Lond reganarrived to register their marriages Foley's minions would alert him and he wouldrush to the m arriage bureau to present them with a wedding gift. Diver tired of ar-riving later at the couple's home with his present, and by the end of the campaignhad taken to po sting his own spy. T he re w ere similar races to console newly madewidows with money for an undertaker, carriages for the mou rners , and coal for thestove.

For the wedding of the daughter of a prominent constituent Foley learnedthrough his spies that Diver was preparing to give silver place settings. H e dupli-cated the gift and trumped Diver with a silver tea set. Rather than pursue asym-metric strategies, these rivals bid against each other for the same voters and withvirtually equal offers.

Of course, knowledge of the com munity may also confer a special ability at ex-tracting revenues. Corruption within the local police department in the manage-me nt of the public docks and the practice of extracting dues from governm entemployees who owed the ir jobs to th e mach ine also gave machine po liticians privi-leged means of extracting revenue from their core constituencies that w ould havebeen more costly to use outside the core.

T h e advent of civil service greatly limited th e benefits the political m achines hadavailable to distrib ute, making their specialized knowledge of individuals' c ircum -stances less valuable. Other broad-brush means of redistribution were equallyavailable to both parties leading to the use of more symmetrical redistributivestrategies.

The examples appearing in this section are provided as illustrations of the logicbehind ou r theoretical results. No ne is offered as a test of our model. Carefultesting of the model awaits detailed data on the distribution of political viewswithin and across interest groups, including both the groups that receive subsidiesand, very importantly, those that do not. W hat th e examples are designed to pro-vide is some substantive intuition about the theory developed in the precedingsection.

T h is analysis compared the swing voter view of redis tribu tive politics withthe perspective emp hasizing mem bers hip in core political con stituen cies as a de-terminate of success. Swing groups have relatively many political moderates,nearly indifferent between th e partie s on the basis of policy position and traditionalloyalties, and more likely to switch their votes on the basis of particularisticbenefits. T he se gro ups benefit when the p arties have no special skills at conveyingbenefits to, or taxing, any core su pp ort g roups. If suc h advantages exist, the p artieshave a very real incentive to cultivate core groups with which the parties can usetheir special understanding of the voting community to target particularistic

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

19/27

1149h e D eterminants of Success of Special InterestsIn related work, Dixit and Lo ndreg an (1995), we generalize the m odel to a dy-

namic settin g in which political parties use of red istribu tive political benefits toattract voters has the unintended effect of impeding the adjustment to economicshocks. The model constructed here could also be generalized to allow for moregeneral, nonlinear, deadweight losses from taxation and subsidy. We suspect thatmany econom ically inefficient policies, from the use of im po rt tariffs to protect de-clining industries, to th e pay ment of agricultural subsidies, to disaster aid for floodvictims used to reconstruct housing in areas in peril of reflooding fit within theframework of the model of redistributive politics con structed here.Manuscript submitted 20 September 1994Fin al manuscript received 12 December 199 5

Here we validate the intuition developed in the Analysis section of the text byformally characterizing the Nash eq uilibrium .

Recall that p arty L chooses its strategy, namely its transfers (T L , i 1 ,2 , G),to maximize its vote total given by (2), subject to the bud get constraint (7), andparty R similarly chooses its (T R ) o maximize (3) subject to its bud get c onstrain t.A pure strategy Nash equilibrium is defined as a situation whe re each party s strat-egy is optima l for it, given the strategy of the o the r party.

First we examine the existence of equilibrium in our model. The standardsufficient cond itions for the existence of Nash equilibrium are given by Glicksberg sTheorem; see Fudenberg and Tirole (1992, 34). These conditions are that eachplayer s payoff is a quasiconcave fun ctio n of his or her own strategy, and a contin u-ous functio n of the othe r player s strategy. In o ur m odel, the c on tinu ity is obvious.To get the quasi-concavity, note the ch ain by which the strategies affect the paoyffs.For par ty L , (8 ) and (9 ) define the t , ~ctually received or paid by each member ofgroup i as an increasing and concave func tion of the strategy T L .Nex t, (10) definesC IL s an increasing linear functio n of tiL T h e n (1) defines X as an increa sing con-cave functio n of CIL Finally, from (2), is an increasing func tion of X I ; it is con-cave if the cum ulative d istribution func tion Q l(X1) s concave. If this last assump-tion is made, then the chain is complete and V is a concave (and thereforequasi-concave) fun ction of (T L ). A similar argu me nt applies to y a nd ( T R ) , h eonly difference being that y is a decreasing fun ction of X I and X I is a decreasingfunction of CIR.

In previous literature, Cox a nd M cC ub bin s (1986) assume exactly such concav-ity of the distribution func tion. Lindbeck and W eibull(1993) directly assume quasi-concavity of the payoff func tion, bu t if one tries to trace this back in th eir m odel,it would entail a similar assum ption for the distribution functio n. Howe ver, cumu -

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

20/27

1150 Avinash Dixit and John Lond reganportion where the corresponding probability density function is increasing. For-tunately, there a re othe r links in th e chain that con tribute to concavity, and we willassume that the utility function is sufficiently concave to offset any failure of con-cavity of the distribution func tion, and ensu re quasiconcavity of the payoff func-tion. M oreover, in th e special examples of the general model th at give us many use-ful insights, we can calculate a unique equilibrium explicitly, and do not need torely on a general existence theorem .

Next we consider the conditions that ensure an interior equilibrium. Note thatthe m arginal effect of (T L )on 5 is

As TLgets negative and large in numerical value, CILeventually goes to zero. Weassume that at this point the marginal utility U , (C rL ) oes to infinity, as is the casein the special form (5). If the den sity &(X i) is positive at this point, the n th e mar-ginal benefit to party L from making TL a little less negative will be infinite.Therefore, the party will not drive group i to this low level of consum ption. Sincewe do not expect political red istribution to drive some grou ps down to zero con-sum ption, this seems a reasonable con dition to assume.

At the other end of the spectrum , consider a situation w here Tr s so large tha tall members of grou p i are voting for par ty L . If either the den sity + , X i ) is verysmall at this point, that is, group i has very few ex trem ists who favor party R, or themarginal utility U\(CjL) s very small, that is, a very high level of consumptionmu st be given to this group to win over the last of them , then the de rivative aboveis very small, and par ty L would find it desirable to give a little less to grou p anduse its budget to woo some other grou p. Of these two conditions, th e first (few realextremists) seems reasonable. Also, interior equilibria suffice to bring out the re-sults concerning th e determ inants of political success. Th ere fore we assume such acondition, and henceforth treat only interior equilibria.T h e constrained m aximization problem for party L has the Lagrangian:

T h e Lagrange mult iplier XL is the value to party L, m easured in votes, of an addi-tional dollar available for tactical redistribution . T h e reciprocal of the m ultiplier isthe marginal cost to party L of buying an add itional vote. T h e first orde r condi-tions for a maxim um are:

a at ^N, +, (X i) U1i c r ~ ) TL hL 0 for all i

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

21/27

1151h e D eterminants of Success of Special InterestsWe can similarly co nstruct th e maximization problem for pa rty R; its first orderconditions are just like (13) with the Lagrange multiplier XR instead of hL. T h e

Nash equ ilibrium is to be found by solving all the first-order con ditions and thebud get con straints simultaneously.Even before we do so, we see one important aspect of the equilibrium empha-

sized in our intuitive discussion. The group sizes N, factor out of the first-orderconditions. T h e num bers do affect the total national product , y , and thereforehave some ind irect effect on what individuals get. But the direct effect via the po-litical process is absent. A larger group has more voters to be won, but the bud-getary cost of winn ing them is also proportionately highe r.

M ore exp licit solution s to the mod el can be derived by specializing th e struc tureto reflect the two cases we discussed above.

The Swing Vbter CaseH er e we focus on differences across grou ps in their political preferences distrib-

utions @ ,( X i) nd ut i l ity functions u ( C l ) . Since the leaky bucket aspects are tan-gential to this, we simplify the algebra by leaving them ou t. Th u s, we assume forthe purp ose of this subsection tha t t,k l b for all grou ps and both parties.

T h is allows us to simplify the b udg et constraints. Mu ltiplying e qua tion (10) foreach grou p by the group s size N ,, sum min g across groups and u sing the budgetconstraint (7) we have

where Y 2 N , y is the total p retransfe r income of all groups.Consider party L. Its first-order co ndition s now becomeDividing by + ,(X i) and solving for CIL,we have

where Hi is the inverse of the marginal utility function. Multiply these by N, andadd , and use (14) above to get

Since each U , is a decreasing fun ction, each Hiis a decreasing func tion. Th ereforethe left-hand side is a decreasing function of XL, and therefore the equ ation defines

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

22/27

1152 Avinash Dix it and John Lon dreg anMoreover, the equation does not involve any party-specific information any-

where else. Similar steps for party R will yield an identical equa tion for h R .Therefo re the solut ions mu st be equal: hL h R .Bu t then the two parties first-ord er cond ition s yield C,L C,R for all i, and therefore (1) yields X , 0 for all i.

In oth er words, the two parties chase the same grou ps of voters. I n equ ilibriumtheir promises of transfers cancel each other out, and the vote is exactly what itwould have been if neithe r party had offered any tactical redistribu tive transfers atall. But zero transfers would not constitute an equilibrium. Starting from such aposition, each party has an incentive to try to win over some voters from thegroups that are electorally more attractive, and the process drives both parties tothe equ ilibrium described above.

To get a clearer understanding of which groups do well in the equilibrium, ithelps to consider the special utility function (4). Using this in equ ations (15) and(16) and similar equations for party R, and remembering that X , 0 in equilib-rium, we have,

where h k is the com mon Lagrange mu ltiplier for the two parties, an d we define

Usin g the b udg et con straint, solving for Xk, and substituting , c onsu mp tion C, ofeach me mb er of any particula r grou p (same whichever party the transfer comesfrom ), is given by

c r ( Y B ).i iniT h e solution is as if the governm ent collects all the o utpu t Y that is produced by

the whole electorate, adds o n th e extra bud get B (if any) available for tactical redis-tribution, and divides the result, each person getting a share proportionate tohis/her group s r , . Therefore, the rj defined in (17) serve as measures of thegroup s political power in achiev ing red istribu tive benefits. We can get an unde r-standin g of the de termin ants of success in redistributiv e politics by examining thecomp onents that go, or do not go, into the .rr,.

M ost importantly, r is highe r when K is higher-group j s vote is more respon-sive to econom ic favors-and when +,(O) is higher-members of gro up are moredensely located at the center of the ideology spectrum between the parties, in thesense tha t they would be close to indifference if the two parties offered th em equaleconomic favors.Next, note that the .rr, do not involve N,-group size does not affect politicalpower either way. Group size does affect the total amount available for redistribu-

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

23/27

1153h e D eterminants of Success of Special Interests

If NJ is very large, then the j-th term dom inates the sum s in both the nu me ratorand the denominator of the fraction on the right hand side, so the fraction is ap-proximately Y/T and C, approximately equals Y . In other words, large groupstend t o get tactical redistri bu tive trea tment t hat is closer to being neutral-neitherlarge transfers nor large taxes.

F inally , when is large, 1 / ~s small, which tends to make all the .rr, close to 1.T h en CJ ( Y B)/N, where N N is the total popu lation. Th u s everyonegets equal consum ption-the poorer grou ps (low receive transfers, and thericher ones (high pay taxes. T h e reason is that the parties find the poor voterseasier to attract with economic transfers, not that they favor equality on ethicalgrounds.The Core Support Case

Now we introduce the parameters elkand l hat measure differential abilitiesof parties to deliver benefits to or raise taxes from particular groups. As we statedbefore, we believe that differences in the ability to deliver benefits (different elk)are the more likely situation in reality; differences in th e ability to tax are includedfor logical com pleteness.

T h e ad ditiona l parameters make a general analysis very messy, bu t sufficient un-derstan ding can be achieved by considering just two groups, and the special form(4) of the utility function. We also suppose that the distribution of each group'smembers is uniform, thus

i whenl , X0 otherwise.Of course 6, I/(? , I,) to keep the total mass equal to 1. W hen 6i is large,(r, 1, is small, and g roup i is ideologically more concentrated. Of course we as-sume that the range (I,, r,) of the distributions of ideological preferences aresufficiently wide to rule ou t corner solutions in wh ich one of the gro up s is en-tirely bought by one of the political par ties.T h e derivative of pa rty L's Lagrangian (12) with respect to T,L is

Party L will tax gro up 2 to subsidize group 1 if and only if this derivative is positiveas qLincreases start ing at 0. T h e condition for that is

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

24/27

1154 Avinash Dixit an d John Lond reganLikewise, the condition for party L to tax group 1, using th e proceeds to subsidizegrou p 2, is

If the right hand side expression in these inequalities takes on an intermediatevalue, party L will not engage in transfers TiL= TZL 0):

Similar conditions apply for par ty R.Th ese cond itions clarify the implications of allowing the pa rties to differ in their

abilities at subsidizing the various voting blocks. T h e ratio

can be tho ug ht of as gauging those aspects of the relative political clout ofgroup 2 which are the sam e for both parties. H igher income for group 2 relative togroup 1 makes it a more attractive target for redistributive taxes. T h is is because,all else equal, wealthier individuals a re less willing to compromise their ideologicalviews for particularistic benefits.

Group 1 will fare better than group 2 in the game of tactical redistribution if[ l ] group 1 is more co ncentrated than is group 2, that is, S1/82s large, and[2] group 1 me mb ers have greater intrinsic willingness to comprom ise on t he ideo-logical issue in exchange for particularistic benefits than do members of group 2,that is, KI ~2 is large.

All the results thus far are the sam e as in the sw ing voter case. Mach ine politicsconsiderations enter through the relative advantages of th e pa rties at subsidizingand taxing different groups. Recall that ou r concept of a grou p being a coregroup for a party is measured by the magnitude of the 0 and coefficients; for acore group these are close to zero. W hen both groups are close to the core ofparty L, the two expressions on the e xtreme e nds of the chain of inequalities (18)are each close to 1 and therefore the two are close to each o ther. S o party L willonly refrain from redistributive transfers when the groups have very similarclout. If both g roup s are distan t from the core, party L will refrain from redis-tributive transfers over a wide range of values of political clout.

Being in the core of one of the p arties can be a mixed blessing when this entailslower sensitivity to taxes levied by the party as well as greater receptiveness totransfers: parties may find it in their in terest to exploit the good will of their coreconstituents by taxing them mo re heavily, and lavishing the p roceeds o n less loyalgrou ps of responsive swing' voters. But in practice we expect th e differential sen-

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

25/27

T h e Determ inants of S uccess of Special Interests

Allen, Oliver E. 1993. The Tiger: Th e Rise and Fall of Tam many Hall. New York: Addison-Wesley.Baldwin, Robert E. 1985. The Political Economy of U.S. Import Policy. Cambridge, MA: M I T Press.Cox, Gary W., and M atthew D . McCubbins. 1986. Electoral Politics as a Redistributive Gam e.

Journal ofpolitics 48:370-89.Dixit, Avinash, and John Londreg an. 1995. Redistributive Politics and Econom ic Efficiency. Ameri-

can Political Science R evie w 89:856-66.Downs, Anthony. 1957. A n Economic Theory ofDemocracy. New York: Ha rper and Row.Fuden berg, Drew, and Jean Tirole. 1992. Game Theory. Cambridge, MA: M I T Press.Hufbauer, Gary C., Diane T Berliner, and Kimberley A. Elliott. 1986. Trade Protection in the United

States: 31 Case Studies. Washington, DC : In stitute for International Economics.Lindbec k, Assar, and Jorgen Weibull. 1987. Balanced-budget Redistribution as the Ou tco me of

Political Com petition. Public Choice 52 :272-97.Lindbec k, Assar, and Jorgen Weibull. 1993. A Mod el of Political Equilibrium in a Represe ntativeDemocracy. Journal of Public Economzcs 51 195-209.

Mye rson, Roger B. 1993. Incentives to Cultivate Favored Minorities Und er Alternative ElectoralSystems. American Political Scrence Review 87 856-69.

Pu rdum , Tod d S. 1994. In Political Power Gam e, It's Advantage, California, New York TimesMarch 8, p. B1.

Rakove, Milton, 1975. Don t Ma ke N o Waves, Don t Back No Losers. Bloomington, IN: IndianaUniversity Press.

Riker, William H . 1982. Liberalism Ag ainst Populism. San Francisco: W . H Freeman.Riordan, William L 1963. Plunkitt of Tammany Hall. Toronto: Clarke and Irwin.Shepsle, Kenneth A. 1991. Models of Multi par ty Electoral Competition. Reading, UK: HarwoodAcademic.Shepsle, Kenn eth A,, and Barry R. Weingast. 1981. Political Preference for the Pork Barrel: A

Generalization. Ame rica n Journal of Political Sczence 25 96- 11 1.Avinash Dixit is professor of economics, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ08544-1021.John Londregan is assistant professor of political science, University of Cali-fornia, Los Angeles, CA 90095.

-

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

26/27

You have printed the following article:

The Determinants of Success of Special Interests in Redistributive Politics

Avinash Dixit; John Londregan

The Journal of Politics, Vol. 58, No. 4. (Nov., 1996), pp. 1132-1155.

Stable URL:

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-3816%28199611%2958%3A4%3C1132%3ATDOSOS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-S

This article references the following linked citations. If you are trying to access articles from anoff-campus location, you may be required to first logon via your library web site to access JSTOR. Pleasevisit your library's website or contact a librarian to learn about options for remote access to JSTOR.

[Footnotes]

5 Electoral Politics as a Redistributive Game

Gary W. Cox; Mathew D. McCubbins

The Journal of Politics, Vol. 48, No. 2. (May, 1986), pp. 370-389.

Stable URL:http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-3816%28198605%2948%3A2%3C370%3AEPAARG%3E2.0.CO%3B2-9

References

Electoral Politics as a Redistributive Game

Gary W. Cox; Mathew D. McCubbins

The Journal of Politics, Vol. 48, No. 2. (May, 1986), pp. 370-389.

Stable URL:

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-3816%28198605%2948%3A2%3C370%3AEPAARG%3E2.0.CO%3B2-9

Redistributive Politics and Economic Efficiency

Avinash Dixit; John Londregan

The American Political Science Review, Vol. 89, No. 4. (Dec., 1995), pp. 856-866.

Stable URL:

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0003-0554%28199512%2989%3A4%3C856%3ARPAEE%3E2.0.CO%3B2-P

http://www.jstor.org

LINKED CITATIONS- Page 1 of 2 -

NOTE:The reference numbering from the original has been maintained in this citation list.

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-3816%28199611%2958%3A4%3C1132%3ATDOSOS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-S&origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-3816%28198605%2948%3A2%3C370%3AEPAARG%3E2.0.CO%3B2-9&origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-3816%28198605%2948%3A2%3C370%3AEPAARG%3E2.0.CO%3B2-9&origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0003-0554%28199512%2989%3A4%3C856%3ARPAEE%3E2.0.CO%3B2-P&origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0003-0554%28199512%2989%3A4%3C856%3ARPAEE%3E2.0.CO%3B2-P&origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-3816%28198605%2948%3A2%3C370%3AEPAARG%3E2.0.CO%3B2-9&origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-3816%28198605%2948%3A2%3C370%3AEPAARG%3E2.0.CO%3B2-9&origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-3816%28199611%2958%3A4%3C1132%3ATDOSOS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-S&origin=JSTOR-pdf -

8/12/2019 Dixit Etal 96

27/27

Incentives to Cultivate Favored Minorities Under Alternative Electoral Systems

Roger B. Myerson

The American Political Science Review, Vol. 87, No. 4. (Dec., 1993), pp. 856-869.

Stable URL:

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0003-0554%28199312%2987%3A4%3C856%3AITCFMU%3E2.0.CO%3B2-C

Political Preferences for the Pork Barrel: A Generalization

Kenneth A. Shepsle; Barry R. WeingastAmerican Journal of Political Science, Vol. 25, No. 1. (Feb., 1981), pp. 96-111.

Stable URL:

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0092-5853%28198102%2925%3A1%3C96%3APPFTPB%3E2.0.CO%3B2-A

http://www.jstor.org

LINKED CITATIONS- Page 2 of 2 -

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0003-0554%28199312%2987%3A4%3C856%3AITCFMU%3E2.0.CO%3B2-C&origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0092-5853%28198102%2925%3A1%3C96%3APPFTPB%3E2.0.CO%3B2-A&origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0092-5853%28198102%2925%3A1%3C96%3APPFTPB%3E2.0.CO%3B2-A&origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0003-0554%28199312%2987%3A4%3C856%3AITCFMU%3E2.0.CO%3B2-C&origin=JSTOR-pdf