ajr.04.1563

-

Upload

reza-pramayudha -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

description

Transcript of ajr.04.1563

AJR:186, March 2006 833

AJR 2006; 186:833–836

0361–803X/06/1863–833

© American Roentgen Ray Society

M E D I C A L I M A G I N G

A C E N T U R Y O F

M E D I C A L I M A G I N G

A C E N T U R Y O F

Strife et al.Frequency of Radiology Reporting of Childhood Obesity

Pe d i a t r i c I m ag i n g • O r i g i n a l R e s e a rc h

The Frequency of Radiology Reporting of Childhood Obesity

Janet L. Strife1

Raymond E. DecanioLane F. DonnellyNeil D. Johnson

Strife JL, Decanio RE, Donnelly LF, Johnson ND

Keywords: obesity, pediatric radiology, radiology practice

Received October 5, 2004; accepted after revision February 7, 2005.

DOI 10.2214/AJR.04.1563

1All authors: Department of Radiology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave., Cincinnati, OH 45229. Address correspondence to J. L. Strife.

OBJECTIVE. The purpose of our study was to review the current practice of radiologistswith respect to dictating the presence of obesity in imaging reports.

MATERIALS AND METHODS. Over 1 million radiology reports dictated at a large pe-diatric hospital from 1994 to 2002 were analyzed for several keywords relating to obesity. Thenumber of cases in which the keywords appeared was recorded for each year, and a percentagewas calculated. Reports done in 1999 and 2000 were further analyzed to determine where thekeywords were positioned within the report.

RESULTS. The number of reports containing a keyword ranged from 131 to 456 per year.During each year, documentation of obesity occurred in less than 0.4% of all reports. Duringthat same time period, the national prevalence of pediatric obesity ranged from 6–16%. De-tailed examination of the 1999 and 2000 reports showed that even in the reports that mentionedobesity, it was usually not listed in the diagnostic impression.

CONCLUSION. Despite the increase in public awareness of obesity and increasing rec-ognition of obesity-related disease, this study did not find a similar awareness among radiolo-gists at a large pediatric radiology department. The reason for this discrepancy is speculativeand likely multifactorial. Regardless, radiologists may be missing an opportunity to play a rolein disease prevention and early recognition by documenting findings of obesity and therebybringing them to the attention of referring physicians.

hildhood obesity has reached epi-demic proportions in the UnitedStates, and its prevalence contin-ues to increase. Since 1980, the

number of obese children has more than dou-bled [1, 2]. The American Academy of Pediat-rics [3] states that childhood obesity poses anunprecedented burden in terms of children’shealth and present and future health care costs.Pediatric obesity not only negatively affectsself-esteem and quality of life, but also causesserious secondary medical sequelae. Obesityin childhood also frequently leads to obesity inadulthood. In adults, obesity outranks smokingand drinking as having a greater deleterious ef-fect on health and health costs [4].

Significant effort is being made by themedical community to develop a treatmentplan to combat this epidemic in children.However, effective treatment is and willcontinue to be dependent on the recognitionof obese patients by their care providers.Radiologists are trained to identify potentialhealth risks on imaging studies and reportthese findings to referring physicians.

The purpose of this study was to review thecurrent practice of radiologists at a large pe-diatric institution with respect to dictating thepresence of obesity in the imaging report. Theresults were then compared with the nationalprevalence of pediatric obesity.

Materials and MethodsCincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

has had a computer-based radiology informationsystem since 1990. Radiology reports dictated from1994 to 2002 were reviewed and analyzed. Approvalfrom the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Internal Re-view Board was obtained. Patient identities weremasked to protect confidentiality according to thestandards set forth by the Health Insurance Portabil-ity and Accountability Act of 1996.

Reports on imaging studies done on childrenunder 1 year old were eliminated from review be-cause of the large number of premature infants andthe exceedingly low incidence of obesity in thatage group. All other reports were subjected to aword search for the following keywords: obesity,obese, excessive soft tissue(s), heavy, overweight,abnormal body habitus, and excessive fat. The

C

Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

jron

line.

org

by 1

14.1

24.3

4.61

on

05/2

7/14

fro

m I

P ad

dres

s 11

4.12

4.34

.61.

Cop

yrig

ht A

RR

S. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly;

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved

Strife et al.

834 AJR:186, March 2006

number of cases in which the keywords appearedin the report was recorded for each year. The num-ber of reports containing a keyword was then di-vided by the total number of reports dictated dur-ing that same year, then multiplied by 100 so thata percentage could be calculated.

The subset of reports done in 1999 and 2000were subjected to further analysis to determinewhere the keywords were positioned within the re-port (clinical history, descriptive findings, or diag-nostic impression). If a keyword appeared morethan once in a report, the location of the word wasassigned to the portion of the report closest to di-agnostic impression. In addition, the context ofthe keywords was evaluated to determine whetherthe words were used in reference to large bodyhabitus. Those that were not were consideredfalse-positive search results. For example, a reportmay contain the keyword “heavy,” but in the con-text of “heavy-duty wire” or “heavy object fell onfoot.” The keyword in this case would be recordedas a false-positive. However, those reports con-taining false-positives were not eliminated fromthe total count of reports containing a keyword.Positive reports were also analyzed to evaluatewhich radiology modalities were used most fre-quently when mentioning keywords.

ResultsOver 1 million radiology reports were ana-

lyzed. The number of reports containing akeyword ranged from 131 to 456 per year.

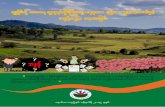

During each of the 9 years reviewed, docu-mentation of obesity occurred in less than0.4% of all radiology reports (Fig. 1). Duringthat same time period, the national prevalenceof pediatric obesity ranged from 6–16% de-pending on age and sex [1, 2].

When the 1999 and 2000 reports were fur-ther examined, it was found that a significantnumber of the dictated reports containedfalse-positives and relatively few includedobesity as part of the diagnostic impression(Table 1). False-positives were included inthe overall data and, thus, there was actuallyunderrepresentation of the percentage of timethat keywords were used to describe an obeseor overweight child. Table 2 describes the dis-tribution of modality-specific volume and thepercentage of cases where keywords wereused. Radiography contributes to 73% of thevolume of cases, and it also was the mostcommon imaging technique where keywordswere used to recognize obesity.

DiscussionThe number of obese children has more than

doubled in the past 25 years. Data from the sec-ond National Health and Nutrition Examina-tion Survey (NHANES) (1976–1980) [1]showed that the prevalence of childhood obe-sity (defined as a body mass index of 30 orhigher) was approximately 5–6%. The thirdNHANES (1988–1994) [2] data showed that

Fig. 1—Percentage of reports containing keywords according to year. Prevalence of childhood obesity in 1994 and 2002 (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data) are also shown.

Year

Per

cen

t

0

2

4

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002

11

16

0.3150.3520.3280.2730.2860.2480.2470.1530.226

number to have increased to 10–11%, depend-ing on age group and sex. Data collected from1999 to 2002 showed a continued increase inprevalence, with percentages over 16% [2].

Although childhood obesity frequently af-fects self-esteem and quality of life, it canalso result in dysfunction of multiple organsystems even in the pediatric population [5].Approximately 60% of overweight childrenand adolescents have at least one additionalrisk factor for cardiovascular disease, such aselevated blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, orhyperinsulinemia [6]. More than 25% havetwo or more of these risk factors. Liver steato-sis, obstructive sleep apnea, and early puber-tal maturity are all associated with obesity inchildren [7, 8]. Orthopedic problems may re-sult as well, including slipped capital femoralepiphysis and tibia vara [9, 10].

The childhood years are a critical time forobesity management. In their review of theliterature, Serdula et al. [11] found that aboutone third of obese preschool children wereobese as adults, and about half of obeseschool-age children were obese as adults.Overall, the risk for adult obesity was at leasttwice as high for obese children as for non-obese children. Dietz [12] also stated that ap-proximately 50% of obese adolescents with a

TABLE 1: Where the Keywords Were Found in an Analysis of Radiology Reports from 1999–2000

Location in the Report 1999 2000

Clinical history 28 30

Descriptive findings 134 231

Diagnostic impression 27 79

False-positivesa 112 61

Total 301 401aFalse-positives (e.g., “heavy-duty wire”) were included in the overall data.

TABLE 2: Modality-Specific Dictation of Obesity Compared with Volume of Cases in 2000

Method

Cases Using Key Terms (%)

(n = 340)

Departmental Volume (%)(n = 151,000)

Radiography 81 73

Sonography 11 9

CT and MRI 8 13

Interventional 0 2

Nuclear medicine 0 3

Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

jron

line.

org

by 1

14.1

24.3

4.61

on

05/2

7/14

fro

m I

P ad

dres

s 11

4.12

4.34

.61.

Cop

yrig

ht A

RR

S. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly;

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved

Frequency of Radiology Reporting of Childhood Obesity

AJR:186, March 2006 835

body mass index at or above the 95th percen-tile become obese adults.

In addition, treating obesity during child-hood may be easier than during adulthood. Un-healthy eating and activity patterns have notbeen in place as long, family support is usuallymore consistent, and treatment of obese chil-dren can take advantage of increases in leanbody mass as the child grows. Early treatmentcan also prevent the development of excess ad-ipose cells instead of shrinking them [13].

Pediatric obesity that persists into adult-hood brings myriad complications. Glucoseintolerance, type 2 diabetes, hypertension,dyslipidemia, and coronary heart disease areall closely associated with obesity [14]. As inchildren, liver disease, gallbladder disease,and obstructive sleep apnea are all comorbidconditions [15]. Obesity in adults has alsobeen associated with menstrual irregularityand infertility, osteoarthritis, gout, venous in-sufficiency, and certain forms of cancer[16–18]. Weight loss can and often does elim-inate many of these conditions, and a reducedmortality among weight-reduced individualshas also been recently reported [19].

It is clear that pediatric obesity is epidemicand that prevention and treatment of this dis-ease are of paramount importance. However, itis also clear that at-risk children are not consis-tently being identified. One review of pediatriccharts showed that providers documented obe-sity in only 53% of obese patient visits (rang-ing from 31% in preschoolers to 76% of ado-lescents) [20]. In the same study, obesity wasonly documented at the physical examination39% of the time. Another report of surveyeddoctors indicated that only 50–61% routinelyinitiated treatment in overweight children withno obesity-associated medical conditions [21].Many obese children who are at high risk forserious comorbid conditions now and duringfuture adulthood are being missed.

Radiologists are relied on to examine im-aging studies for findings that may reflect dis-ease or potential disease and to report those tothe referring physician. Much of what is re-ported is subjective, with the impressionsbased on the radiologist’s experience andtraining. It is expected that subjective findingssuch as osteoporosis will be looked for, doc-umented, and reported to the referring physi-cian because of the relation to potential healthrisk. However, our study found that radiolo-gists reported obesity in fewer than 0.4% ofcases, while the incidence of obesity in thepediatric population during that time periodapproached 16%. Even in cases where obesity

was documented, it was frequently not in-cluded in the diagnostic impression.

The reason for this discrepancy between theincidence of obesity in pediatric patients andthe notation in the radiology reports is specula-tive and likely multifactorial. It could be ar-gued that no standard measurements forimaging obesity currently exist. However, radi-ologists routinely document other observationsthat are not based on an actual measurement,such as osteopenia, peribronchial cuffing, andheart size. The negative social connotation ofobesity may deter some from documenting it ina report. Others may avoid it because of fear ofmedical liability, although we would argue thatthere is a danger of medical liability in not re-porting it. Some radiologists may avoid listingobesity as a diagnosis for fear of affecting thepatient’s insurance status, although cliniciansoften list tobacco use and other high-risk be-haviors as diagnoses.

Finally, many radiologists self-report thattheir primary reason for not documenting obe-sity is that it is fairly obvious on physical ex-amination (Strife JL, unpublished data). How-ever, just because something is obvious onexamination does not mean that it is being ad-dressed. The patient who presents with gall-stones and who is obese with CT findings offatty liver needs to have the obesity reportedbecause of its relation to the disease process.The obese adolescent patient who presents tothe emergency department with knee or hippain should not be told that the radiographs are“normal,” especially if there are inches of soft-tissue fat. There is a well-known associationbetween slipped capital femoral epiphysis andthe immature skeleton and obesity. It is the ra-diologist’s responsibility to try to prevent fur-ther disease by reminding the clinical care pro-viders of the morbidity and potential riskassociated with obesity in that patient.

The limitations of the study include the factthat not all reports were actually interpreted.The computer searched for keywords indicat-ing obesity and other terms may have been usedin addition to those specified. In this respect, itwould lead to an underestimation of obesity in-dicating a disease. On the other hand, false-pos-itives were included in the overall data and,thus, there is actual underrepresentation of thepercentage of time that certain keywords wereused to describe an obese child. In addition, thedistribution of radiology modality-specificwork volume is relevant. In certain studies suchas neuroimaging and nuclear medicine imag-ing, appreciation for obesity may be limited. Inthis respect, these volumes of cases contribute

to an overestimation of obesity. Regardless ofthe limitations, a big discrepancy exists in thenotation of obesity and the well-known in-crease in prevalence of the disease. No substan-tial change has occurred in the notation of obe-sity in radiology reporting over the past 8 yearsdespite the increase in prevalence and recogni-tion by other subspecialties.

Former Surgeon General C. Everett Koopstated that obesity is the number one medicalissue the nation faces and warns that it is dif-ficult to justify complacency in the face ofthis growing epidemic now affecting morethan 58 million Americans [19]. The Amer-ican Academy of Pediatrics [3] has statedthat it is incumbent on the pediatric commu-nity to take a leadership role in preventionand early recognition of pediatric obesity.Radiologists can and should be involved inearly recognition by documenting findingsof obesity and thereby bringing them to theattention of the referring physician.

References1. Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, et al. Prev-

alence and trends in overweight among US chil-

dren and adolescents, 1999–2000. JAMA 2002;

288:1728–1732

2. Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, et al. Prev-

alence of overweight and obesity among US chil-

dren, adolescents, and adults, 1999–2002. JAMA

2004; 291:2847–2850

3. Krebs NF, Jacobson MS; American Academy of Pe-

diatrics Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of pe-

diatric overweight and obesity. Pediatrics 2003;

112:424–430

4. Sturm R. The effects of obesity, smoking, and drink-

ing on medical problems and costs: obesity out-

ranks both smoking and drinking in its deleterious

effects on health and health costs. Health Aff (Mill-

wood) 2002; 21:245–253

5. Schwimmer JB, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Health-

related quality of life of severely obese children and

adolescents. JAMA 2003; 289:1813–1819

6. Dietz WH. Overweight in childhood and adoles-

cence. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:855–857

7. Mallory GB Jr, Fiser DH, Jackson R. Sleep-associ-

ated breathing disorders in morbidly obese children

and adolescents. J Pediatr 1989; 115:892–897

8. Rashid M, Roberts EA. Nonalcoholic steatohepati-

tis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000;

30:48–53

9. Dietz WH Jr, Gross WL, Kirkpatrick JA Jr. Blount

disease (tibia vara): another skeletal disorder asso-

ciated with childhood obesity. J Pediatr 1982;

101:735–737

10. Loder RT, Aronson DD, Greenfield ML. The epi-

Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

jron

line.

org

by 1

14.1

24.3

4.61

on

05/2

7/14

fro

m I

P ad

dres

s 11

4.12

4.34

.61.

Cop

yrig

ht A

RR

S. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly;

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved

Strife et al.

836 AJR:186, March 2006

demiology of bilateral slipped capital femoral epi-

physis: a study of children in Michigan. J Bone Joint

Surg Am 1993; 75:1141–1147

11. Serdula MK, Ivery D, Coates RJ, Freedman DS,

Williamson DF, Byers T. Do obese children become

obese adults? A review of the literature. Prev Med

1993; 22:167–177

12. Dietz WH. Childhood weight affects adult morbidity

and mortality. J Nutr 1998; 128[suppl 2]:411S–414S

13. Epstein LH, Myers MD, Raynor HA, Saelens BE.

Treatment of pediatric obesity. Pediatrics 1998;

101:554–570

14. National Task Force on the Prevention and Treat-

ment of Obesity. Overweight, obesity, and health

risk. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:898–904

15. Sheth SG, Gordon FD, Chopra S. Nonalcoholic ste-

atohepatitis. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126:137–145

[Erratum in Ann Intern Med 1997; 127:658]

16. Scott TE, LaMorte WW, Gorin DR, Menzoian JO.

Risk factors for chronic venous insufficiency: a dual

case-control study. J Vasc Surg 1995; 22:622–628

17. Grodstein F, Goldman MB, Cramer DW. Body

mass index and ovulatory infertility. Epidemiology

1994; 5:247–250

18. Felson DT. Does excess weight cause osteoarthritis

and, if so, why? Ann Rheum Dis 1996; 55:668–670

19. [No authors listed]. Clinical guidelines on the iden-

tification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight

and obesity in adults—the evidence report: Na-

tional Institutes of Health. Obes Res 1998; 6[suppl

2]:51S–209S

20. O’Brien SH, Holubkov R, Reis EC. Identifica-

tion, evaluation, and management of obesity in an

academic primary care center. Pediatrics 2004;

114:e154–e159

21. Jonides L, Buschbacher V, Barlow SE. Manage-

ment of child and adolescent obesity: psychologi-

cal, emotional, and behavioral assessment. Pediat-

rics 2002; 110:215–221

Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

jron

line.

org

by 1

14.1

24.3

4.61

on

05/2

7/14

fro

m I

P ad

dres

s 11

4.12

4.34

.61.

Cop

yrig

ht A

RR

S. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly;

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved