Wang Zhibo | 王之博

-

Upload

edouard-malingue-gallery -

Category

Documents

-

view

251 -

download

6

description

Transcript of Wang Zhibo | 王之博

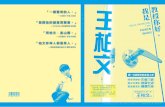

封面:《基座》, 油彩 畫布, 2012, 150 x 200 cm Cover: Bases, oil on canvas, 2012, 150 x 200 cm

《巨浪高企的靜止》 柯蒂斯 L. 卡特 著

Standing Wave by Dr. Curtis L. Carter

紙上作品Works on paper

油彩 畫布Oil on canvas

《王之博的輓歌式園林景色》凱蒂 . 希爾博士 著

The Elegiac Parkscapes of Wang Zhiboby Dr. Katie Hill

簡歷Biography

目錄Contents

5-13

15-19

21-33, 44-59

35-42

60-61

9

柯蒂斯 L. 卡特 著

在香港馬凌畫廊的支持下,王之博得以亮相於2013年度紐約軍械庫藝博會,也標誌著她

繼參與2009年比利時安特衛普美術館群展後,首次進軍西方美術界的重要時刻。1981

年,王之博生於浙江,並一直在杭州生活及工作。2008年,她畢業於中國美術學院油畫

系,獲頒藝術碩士學位。自此,王氏的畫作在中國各地的博物館及畫廊展出。自2005年

第二屆成都雙年展後,王之博曾先後參與2007年上海博物館群展、2008年北京今日美術

館及南京青和當代美術館、2009年國立台灣美術館、2012年北京舉行的中國青年藝術家扶

持推廣計劃,及國內各城市中私營畫廊的展覽等。

王之博紐約之行,正值中國當代藝術在當地的畫廊、博物館,以及歐洲展館的主流展覽中

廣受歡迎之際。她加入了全球藝術家從東方遷徙至西方這一大趨勢,踏上同樣的西征之

路。這風氣始於上世紀八十年代,曾斷續地出現於二十世紀的全球藝術動向,也正是把焦

點從西方轉移至東方的逆轉現象。

當今天才橫溢的新進中國藝術家,包括王之博在内,都致力於尋找一種視覺語言,藉以探

索當代藝術及人類生命複雜的層面。王氏活於一個中國藝術文化及全球大轉變的動亂時期 1。

生活轉變的中國,包括文化大革命後的社會變遷以及在全球化的影響下,中國引進西方藝

術與本土前衛藝術的萌生。王之博及她的同輩面對同一個重要課題:如何在來自西方美術

全球性影響的裨益下保留中國本質。

王氏的藝術根源又可追溯到哪裏?不少當代藝術家把目光投放在個人主觀性之上,視之為

自己的藝術泉源。他們把創作的聚焦放在個人化的美學觀點、自尊、甚至獨立靈性或精

神,把它們當作抗衡不公平、受壓制的社會鬥爭的楔子。現今的藝術家勇於把自我關切具

體化,通過藝術探索人性各方面的意義 2。當然,王之博也不例外。她依靠内心生活作為自

己主要的藝術泉源,對探索超越自我環境的藝術與文化同樣抱著好奇。

當被問及如何評價自己創作的方式,王之博回應道:

「 我 相 信 我 作 畫 的 其 中 一 種 方 式 與 人 類 學 者 的 研 究 方 法 極 為 相 似 , 那 就 是 實 地

考 察 。 唯 一 不 同 之 處 : 我 不 用 長 期 居 住 在 一 些 陌 生 的 文 化 及 國 家 裏 。 我 可 以 四

處 遨 遊 , 又 可 在 互 聯 網 上 及 書 籍 中 涉 獵 圖 像 與 文 字 , 沒 有 影 響 到 自 己 日 常 生

活 , 從 中 發 現 自 己 日 常 生 活 的 種 種 痕 跡 及 細 節 , 原 來 早 已 存 在 於 人 類 文 化 系 統

之 中 , 就 像 原 始 的 社 交 工 具 及 裝 飾 品 , 又 或 是 人 類 學 家 所 探 討 的 建 築 風 格 。 最

關 鍵 的 是 , 這 些 痕 跡 及 細 節 之 間 的 微 妙 關 係 , 可 以 經 時 間 及 空 間 的 改 變 而 更 具

意義。時間是指過去及現在,而空間則是這裡與別處。」3

王之博參與軍械庫藝博會的十三幅作品,全都創作於2012年,以建築空間及地點為主

題,也經常引用大自然。王氏以自己建造的圖像為作畫的主要元素,沒有抄襲客觀世界。

巨浪高企的靜止

1 參考朱莉亞 . 安德魯斯等,《一個世紀危機:

現代與傳統在二十世紀中國藝術》(紐約:古根

海姆博物館,蘇豪,1998)。

2 呂鵬、株株、高建慧等主編,《30年冒險:從

1979年的藝術和藝術家》(香港:Timezone 8,

2011), 149, 175-178頁。

3 王之博訪談 (2013年1月18日) 。

10

她的作品含有象徵性元素,但這些元素大部份都是虛構的,是藝術家根據歷史及今天的圖

像加以想像及創造出來。因此,王之博把建築及雕刻的元素與自然界的現象,包括樹木、

石塊及流水,並列起來。

王氏參與紐約展覽的作品,包括描繪住宅外墻的《我們只是愛美景》、茂林花園般的《人

造黃昏》及偶爾較抽象及強調色彩的構圖《三個挫折》。王氏的畫作予人一種對大自然及

其與建築環境的不同觀點。在這些作品中,大自然與建築的結合並不令人覺得安然,而部

份作品更存在明顯的張力。在《基座》裡,構圖後方的樹木與位於前方的建築及雕刻毗連

一起,給人一種格格不入的感覺。圖像裡的和諧被一種蓄意的雜亂替代了;文化分裂也令

組成畫作的不同元素之間產生不協調的感覺。《無題(後院)》展示一幢現代化的房子,窗旁

放置了一個烤架,圍繞四周的卻是羅馬式圓柱。王之博的畫作散發出一種刻意的雜亂、不

協調的氛圍。縱然她沒有故意傳遞任何關於社會訊息,畫家至少也提供了一個寄予,表明

嘗試將東、西方歷史及當代全球性的複雜文化融合一起,有一定的困難。

那些營造了當今生態及社會動盪的對衡力量,能否復和?也許藝術家在自己的畫作裡捕捉

了它們和諧共存的潛在性。毫無疑問,這裡展示的作品都有一股務求達到安逸的意向,

就像藝術家曾經用過的隱喻:捕捉巨浪高企那靜止的一刻。表面上,巨浪有規律地向前移

動;若對衡力量旗鼓相當,當它們迎頭相撞時,將互相抵消,結果就是瞬間的靜止。王之

博利用這巨浪的隱喻,帶出她的藝術哲學。她透過作品,在人類每天面對著混亂、不平衡

的環境,人工建築與大自然的相互競爭中,創造出巨浪高企的靜止。在王氏的畫作中,往

日的強勢標誌(古典派及文藝復興派的建築及雕刻)與當今建築交於一點,讓觀者有靜思的

空間。《無題(後院)》便是其中的例子。觀者欣賞作品時,因沒有人物的存在,更能享受畫

中的寧靜。或許,正如藝術家自我表述,她刻意把人物排斥於外,好讓建築物(代表人工環

境)與大自然直接對話。

王之博的畫作與中國藝術文化如何拉上關係?有如中國傳統文人的畫作,王氏的風景與室

内場景都是自我思維的創作,不像西方畫作般基於外來事物。那麼,她的畫作所描述的大

自然,是爲了讓觀者聯想起傳統文人的山水畫嗎?也許是的。傳統的文人畫作着重引領觀

者進入及思忖充滿山川、磐石、樹木、池水與瀑布的自然想像。其實,中國古代的帝王園

林同樣企圖創造這種美麗的環境,作為一所令皇族與理想中的大自然靠近的避靜之處。皇

室花園裏井井有條的建築之間,蘊藏著山石、奇異的植物,甚至是小橋流水。傳統中國的

山水畫就是這樣引領觀者在不用置身其中之餘,卻可進入那個理想的自然世界。即使畫中

包括人物,他們也不是主角。

王氏的畫作中沒有人物的存在,是否代表著她向傳統中國畫家人追溯的寧靜安穩致敬?如

果是真的,我們也找得到不少相反的理據。比如説,《綠色故障》明顯地表達一個美麗寧靜的

畫面(水池旁邊種有一株熱帶樹,中央則有供石),但產生出來的效果,卻是一種視覺上的混亂

感。這並不代表作品失敗了。作品故意把觀者的注意力帶到畫中的主題:凸顯今天的混亂時勢

是由不同的文化、思維、環境所引致。另一個相近的主題也在《基座》出現。位於構圖的前方

噴泉前的階梯,是根據仿法國式的園藝設計,但引領至噴泉的卻是中國式樓梯。王氏畫作中的

不和階正好與傳統中國風景畫所表現自然界與人類的和諧及秩序形成直接的矛盾。

在某方面,王之博及她同輩的畫家所面對的,令人聯想起二十世紀初的一群中國畫家,

他們之中包括高奇峰(1889-1933)及高劍父(1879-1951)兄弟創立的嶺南畫派。在同期的

中國畫家中,高劍父的畫作以促進西方美術見稱,目的是以中國及西方藝術的綜合體為基

礎,創立一種新的圖像語言(供中國前衛藝術之用),從而反映中國社會的轉變。他的方法

11

包括運用西方描繪肖像技巧、光影及線條透視於中國傳統文人作畫的筆法、用墨、調色等

技巧 4。

除了高氏兄弟,龐熏琹(1906-1985)及林風眠(1900-1991)等畫家曾赴法國探討馬奈、莫內、

塞尚、梵谷、德蘭、烏拉曼克等畫家繪畫新技法的,嘗試把東、西方美術的分歧縮短5。不同的中

國畫家因著他們在巴黎及西方其他國家的經歷,而選擇把不同的藝術導向帶回祖國。當中包括

前衛派的風格——後印象派、立體派、野獸派、超現實主義、達達主義,都改變了西方傳統的

藝術路向。林風眠選擇把現代主義者馬蒂斯及莫迪里安尼的前衛派風格帶回中國。然而,不是

全部的前衛派風格都是從西方國家而來,好像徐悲鴻(1895-1953)則鍾情於較保守的十八世紀

浪漫現實主義,並以此創作構圖及肖像描繪,以抗衡中國傳統繪畫及西方現代主義的影響6 。

嶺南畫派把政治目的及社會批判都吸納在美學之中,但王之博的畫作則避開任何直接的政

治或社會性。王氏作畫的靈感多來自古典建築及文藝復興時代的美術,她選擇尊崇較古舊

的西方文化,而不是那些曾經吸引二十世紀初中國藝術家的巴黎現代藝術。

這現況凸顯了如何理解不同文化藝術這個問題。不論二十世紀初的中國藝術家或是現今一

代的藝術家得到西方的青睞,都遇上同一個的問題。現今的中國藝術家被接納於西方的美

術世界,接觸新觀眾;但西方觀者也總會產生一個問題,就是如何連繫兩地的文化差異。

近期中國藝術在西方市場上,卻少不免要面對東、西方的文化差異。中國文化藝術那些複

雜堅固的根源,往往對歐美的西方觀衆來説,很難理解。

現今中國美術在西方的成功,只局限於高層次的藝術行業,包括畫廊、收藏家、拍賣行、

博物館及雙年展等,它們只佔據整個市場的一小部分。到現在爲止,西方廣大的觀衆群,

大部分都沒有機會認識中國當代藝術。中國固有的文化及美術觀,能否在西方國家獲得長

久的成功呢?這仍有待觀察。

從上文所述,王之博的畫作融合了西方及中國的美學元素。也許有人爭論,西方美術的傳

統手法會削弱她作品中的中國特性。但是,中國學者許江及高士明則反駁中國畫家運用西

方美術技法,是爲了豐富當代的中國美術發展 7。推而論之,王之博及其他中國畫家的作

品包含西方藝術技法,為西方觀衆建立了橋樑,讓他們可以更了解中國藝術。王之博為中

國當代美術發出了她獨到而清新的聲音。她創造的畫像美輪美奐,同時也為尋找中國美術

的方向提供一條可繼續探索的出路。

柯蒂斯 L . 卡特博士多年來廣於美國及中國教學,是著名的哲

學系美學教授。他的論文多次被收錄在中國大陸的學術期

刊,當中包括北京大學出版社等。卡特博士現於北京一所中

國當代美術館擔任國際策展人。二零零八年三月,卡特博士

被委任為一個專門研究中美兩國文化及教育交流的政府代

表團之一 。

4 Christina Chu,〈嶺南畫派及其追隨者:中國

南方的徹底革新〉,載於朱莉亞 F. 安德魯斯及

Kuiyi Shen,《危機中的一個世紀:現代與傳統

在二十世紀中國的藝術》(紐約:古根海姆博物

館基金會,1998),68頁。

5 高美慶,〈西方風格繪畫運動與二十世紀早期

中國教育改革〉,載於《新亞學術通報》第四卷

(1983),99頁。

6 見邁克爾 . 沙利文,《二十世紀中國藝和藝術

家》(柏克萊及倫敦:加州大學出版社,1996) ,

59、71、72頁。Kuiyi Shen,〈西方的誘惑〉,載

於朱莉亞 F. 安德魯斯及Kuiyi Shen,《危機中

的一個世紀:現代與傳統在二十世紀中國的

藝術》(紐約:古根海姆博物館基金會,1998),

177、178頁。

7 高士明及許江,載於Lee Ambrozy文章“全球

概念”與中國當代藝術的境遇 ,《藝術論壇》。

Com. Cn, SinoPop (2010年7月10日)。

13

Standing Wave

By Dr. Curtis L. Carter

Wang Zhibo’s appearance in the 2013 New York Armory Show, under the auspices of

the Edouard Malingue Gallery of Hong Kong, marks her first venture into the Western

Art World apart from a group showing in Antwerp, Belgium in 2009. Born in Zhejiang

in 1981, Wang lives and works in Hangzhou, China. She earned an MFA degree in oil

painting at the China Academy of Art in 2008. Since then, her paintings have been

shown in an impressive list of museum and gallery exhibitions in China. For example,

since a showing in the Chengdu Biennial in 2005, Wang has participated in group

exhibitions at The Shanghai Museum (2007), the Today Art Museum in Beijing and the

Nanjing QingHe Contemporary Art Museum (2008), the National Taiwan Museum of

Fine Art (2009) and the China Young Artists Project in Beijing in 2012, as well as in

selected private Chinese galleries in various Chinese cities.

In making the journey to New York, Wang joins the global migration of artists from

East to West, where Chinese contemporary art is welcomed into the main stream of

art being shown in New York galleries and museums as well as elsewhere in European

venues. This movement, which began in the 1980s, is a reversal of the direction of

global art from West to East that occurred intermittently throughout the Twentieth

century and beyond.

Like many talented emerging Chinese artists today, Wang Zhibo is in search of a visual

language to explore certain complexities of contemporary art and human life. Her

life span from 1981 to the present marks a period of tumultuous changes in Chinese

art and culture, alongside global changes in the world at large.1 The changes for life

in China encompass the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution and also the influences

of globalization that brought western art and the emergence of avant-garde practices

into Chinese art. A main question facing Wang and others of her generation is how to

maintain some sense of Chineseness in the art while also benefitting from the global

influences arriving from the West.

What then are the likely roots of Wang’s art? A notable portion of today’s artists

look inward to the subjective as the wellspring of their art. These artists focus their

creative output on more personal aesthetic characteristics concerned with self-esteem,

and possibly spiritual autonomy, as a wedge against oppressive societal struggles. For

example, artists today do not shy away from externalizing subjective concerns, using

their art to explore a range of expression that bear on the meaning of humanity.2 It

would not be a surprise to find Wang among those who rely on the inner life as a

principal source of their art, not withstanding her interest in investigating the art and

1 See Julia Andrews et al, A Century of

Crisis: Modernity and Tradition in the Art of

China (New York: Guggenheim Museum,

Soho, 1998).

2 Editors-in-chief: Lv Peng, Zhu Zhu, Kao

Chienhui, Thirty Years of Adventures:

Art and Artists from 1979 (Hong Kong:

Timezone 8, 2011), 149, 175-178.

14

3 Interview with Wang Zhibo on 18

January 2013.

culture beyond her immediate environs.

When asked to comment on her methods for creating art, Wang replied:

“I think I am correct in saying that one of my working methods is similar to

that of an anthropologist. Like he or she, I engage in on-the-spot investigation.

The difference between us, though, is that I do not need to leave China and

live in a different place with an unknown culture and nation for an extended

period of time. I can investigate through travelling as well as learning from

pictures and words found on the internet and in books. I can then combine

these findings with elements from my daily life, which is interesting enough,

I think. I believe that the traces and details of daily life are as central to the

system of human culture as the original social tools, ornamentations, and

architectural styles that are researched by anthropologists. The most

important point is the relationship between these traces and details. These

can be traced meaningfully in time and space, where time refers to the past

and now, and space refers to the here and elsewhere.” 3

The 13 works in Wang’s Armory exhibition created in 2012 feature architectural spaces

and places with frequent references to nature. In these works, Wang focuses mainly on

the constructed pictorial elements that comprise her paintings using these to refer to,

without copying, objects in the external world. The paintings contain representational

elements but the representations are mainly, if not entirely, fictional in the sense that

they are creations of the artist’s imagination using pictorial elements drawn from

history and the present. In this context, Wang juxtaposes architectural and sculptural

elements with images of natural forms, including trees, stones and flowing water.

The spaces explored in Wang’s paintings for the New York show include residential

facades as in We just love the beauty, garden-like spaces with trees as in Artificial

Twilight, and the occasional more abstract pictorial space emphasizing color as in Three

Setbacks. Wang’s paintings offer a different perspective on nature and its relation to

the built environment. The marriage of nature and architecture in these works is not

sanguine. In some of the paintings there is evident tension between architecture

and nature. The trees set in the park as the background of the composition in Bases

appear uncomfortably adjoined with the architecture and sculpture in the foreground.

Harmony inside the pictorial space is replaced by a sense of premeditated disorder.

Cultural disjunctions also contribute to the sense of discord between elements forming

the paintings. In Untitled (Backyard), a modern-looking house with a metal grill over a

window is framed with adjacent Roman style columns. Indeed, a distinct element of

cacophony exudes throughout the paintings. If there is no overt social message, there

is at least the hint that all is not well in the complexities manifest in our attempts to

merge historical and contemporary global cultures of East and West.

Can the opposing forces that contribute to ecological and social unrest today be

reconciled? Perhaps the potential for harmonizing these forces exists in the stillness

captured in the imagination of the artist. Throughout the images shown here there

15

is an unmistakable striving for tranquility that the artist likens metaphorically to

the stillness captured in a standing wave. The wave appears to be constantly moving

forward, but when the two moving forces responsible for the wave are of equal

strength, but operating in opposite directions, they cancel each other out. The result

is then a momentary state of stillness. Wang finds in this metaphor of the wave the

psychological concept underlying her work as an artist. In her paintings, she aims to

create the stillness of a standing wave in the midst of disorder and in-balances found

in the everyday human environments where architecture and nature compete as

opposing forces. The forces of the past (Classical and Renaissance architecture and

sculpture) and the architectural present also converge in Wang’s paintings in ways that

invite reflection. See, for example, Untitled (Backyard). In part, the quietude that one

experiences in viewing these works is heightened by the absence of people. Perhaps, as

the artist hints, she intentionally absents people from her pictorial spaces to allow the

architecture representing the built environment and nature to carry their own revelations.

How are Wang’s paintings connected to Chinese art and culture? As in the traditional

Chinese paintings of the Literati, the landscapes and interiors in Wang’s paintings are

creations of the mind, rather than representations of external nature as it might appear

in western paintings. Are the references to nature in her paintings intended to recollect

in the minds of the viewers the nature tradition found in the paintings of the Chinese

Literati artists? Perhaps in part. Recall, for instance, that pictorial space in the Literati

tradition of painting was intended to invite the viewers to enter into and contemplate

the imagined spaces of nature filled with mountains, rocks, trees as well as ponds

and waterfalls. Indeed, the imperial gardens of enlightened Chinese rulers sought to

create such an aesthetic environment as a refuge to keep them as close as possible to

idealized nature. The imperial gardens included an orderly arrangement of architecture

embellished with rocks, exotic plants and trees, even flowing streams of water.

Traditional Chinese brush and ink paintings extend to the viewer an invitation to enter

into and contemplate the beauties of an idealized natural landscape without actually

being present in the picture space. Even where human figures appear in the paintings,

they do not dominate.

Is the absence of people in Wang’s paintings perhaps a way of paying covert homage to

the peaceful tranquility sought by traditional Chinese artists in their art? If so, there

are never the less contrary forces at work here. For example, in the painting Green

Fault, the elements ostensibly intended to contribute to the tranquil beauty of a scene

(a tropical tree placed near to a pool with scholars’ rocks placed in the center), end

up creating a sense of visual disorder. This is not a failure in the composition. Rather,

the composition draws attention to a main theme in the artist’s paintings: to show

the presence of disorder in today’s world brought about by bringing together in the

environment, and also in our minds, disparate elements of culture. A related theme

appears in the painting Bases. The steps leading to a fountain in the foreground of the

park beyond echo French landscape design, while the steps leading to the fountain carry

a Chinese design. The expressions of disharmony in Wang’s paintings seem in direct

contrast with the traditional celebration of harmony and order existing between nature

and persons reflected in traditional Chinese landscape paintings.

16

In some respects, the situation facing Wang and her generation recalls the circumstances

faced by the generation of Chinese artists in the early part of the twentieth century

that included the Lingnan School of Chinese painting established by the brothers Gao

Qifeng (1889-1933) and Gao Jianfu (1879-1951). Gao Jianfu’s art was influential in the

advancement of Western art ideas among other Chinese artists of the period. His aim

was to create a new pictorial language for the Chinese avant-garde based on a synthesis

of Chinese and Western art suitable to express the changes taking place in Chinese

society. His approach involved attending to portrait painting, lighting and shade, and

linear perspective found in Western art and applying these elements to Chinese brush

strokes, composition, inking and coloring in the manner of the Literati tradition of painting.4

These painters as well as others, such as Pang Xunqin (1906-1985) and Lin Fengmian (1900-

1991) ventured to Paris to explore the new options for paintings including the individual

styles offered by Manet, Monet, Cezanne, van Gogh, Derain and Vlaminck and others, in

an attempt to bridge the gaps between Chinese and Western art.5 The types of Western

influences Chinese artists chose to bring back to China based on their experiences in

Paris and elsewhere in the West varied considerably. Among the choices was a range of

then avant-garde styles - Post-impressionism, Cubism, Fauvism, Surrealism, Dada - all at

work changing the course of Western traditional art. Lin Fengmian (1900-1991) chose

to follow the modernists Matisse and Modigliani in bringing avant-garde modernism

to China. Not all of the influences coming from the West could be considered avant-

garde though. For example, Xu Beihong (1895-1953) favored a conservative Eighteenth

century romantic realism. He used it to create landscape and portrait paintings in

opposition to both Chinese traditional painting and the Western modernist influences.6

Unlike the Lingnan School and its followers, who chose to incorporate political aims

and social critique in their aesthetic, Wang eschews any direct political or social aims

in her art. Taking a longer look backward into Western art, she finds inspiration in

Classical architecture and Renaissance art, choosing to pay tribute to these older

Western cultures instead of the Parisian modern artists that attracted the attention of

Chinese artists earlier in the twentieth century.

This point raises the question of understanding art across cultures. Both the Chinese

artists of the early Twentieth century and the present generation of artists seeking

attention in the west face this issue. It is also the case that as Chinese artists today

enter the Western art world, seeking new audiences, their western viewers must

address the issue of how to bridge the cultural differences represented in such

transitions. Current presentations of Chinese art in western markets require that the

audience be confronted with the issue of cultural differences between East and West

implicit in the shift from a Chinese culture with complex and rich artistic roots not

easily accessible to western audiences in the United States and Europe.

At the present time, the success of Chinese art in the West is mainly confined to the

high end of the art world consisting of galleries, collectors, auction houses, museums,

and biennales that reach a small segment of the population. There is not yet a wide

4 Christina Chu, “The Lingnan School

and Its Followers: Radical Innovations in

Southern China,” in Julia F., Anderson

and Kuiyi Shen, A Century in Crisis:

Modernity and Tradition in the Art of

Twentieth Century China (New York:

Guggenheim Museum Foundation,

1998), 68.

5 Mayching Kao, “The Beginning of

Western-style Painting Movement in

Relationship to Reforms of Education

in early Twentieth-Century China,” New

Asia Academic Bulletin 4 (1983): 99.

6 See Michael Sullivan, Art and Artists of

Twentieth Century China (Berkeley and

London: University of California Press,

1996), 59, 71, 72. And Kuiyi Shen, “The

Lure of the west,” in Julia F. Andrews and

Kuiyi Shen, A Century in Crisis: Modernity

and tradition in the Art of Twentieth-

Century China (New York: The Guggenheim

Museum, 1998), 177, 178.

17

appreciation or understanding of Chinese contemporary art among the western

populous at large, Can the aesthetic values that are grounded in a Chinese cultural

understanding accomplish longer term success in the West? This is a matter that

remains to be seen.

From what has been said already, it is clear that Wang’s art incorporates elements of

both Western and Chinese art. Some might argue that the inclusion of Western art

conventions diminishes the Chineseness of the art. On the other hand, Chinese scholars

Xu Jiang and Gao Shiming have argued that Chinese artists’ employment of Western

art practices serves mainly to enrich the cultivation of contemporary Chinese art.7

Following this line of argument, the presence of western art practices in Wang’s and

other Chinese artists’ work may indeed serve to bridge the understanding of their

art for western audiences. Wang brings to Chinese contemporary art her own voice,

original and fresh. The images are beautifully constructed and mindfully provoking of

thoughts about a direction for Chinese art that invites further explorations.

7 Gao Shiming and Xu Jiang cited in Lee

Ambrozy, “Reading Globalization and

Chinese Contemporary Art”, ArtForum,

July 2010.

Dr. Curtis L. Carter is a renown aesthetics professor who has lectured in the USA as well as across China. Curtis Carter’s essays have been published in numerous Chinese academic journals including the Peking University Press. He now serves as international curator for a contemporary Chinese art museum in Beijing. In March 2008, Curtis Carter was appointed to a governmental delegation that explores cultural and educational exchanges between China and the USA.

紙上作品Works on Paper

20

17#

2012水彩、丙烯、鉛筆 手工紙Watercolour, acrylic, pencil on paper100 x 83 cm

21

22

5#

2012水彩、丙烯、鉛筆 手工紙 Watercolour, acrylic, pencil on paper 26 x 48 cm

23

油彩 畫布Oil on Canvas

26

《無題(後院)》Untitled (Backyard)

2012 油彩 畫布 Oil on canvas135.5 x 155.5 cm

27

28

《我們只是愛美景》We just love the beauty

2012 油彩 畫布 Oil on canvas80 x 96 cm

29

30

《涼的田園詩》Cold Pastoral

2012 油彩 畫布 Oil on canvas89 x 117 cm

31

32

33

《基座》Bases

2012 油彩 畫布 Oil on canvas150 x 200 cm

34

《人造黃昏》Artificial Twilight

2012 油彩 畫布 Oil on canvas215 x 180 cm

35

36

《三個挫折》Three Setbacks

2012 油彩 畫布 Oil on canvas117 x 84.5 cm

39

凱蒂 . 希爾博士 著

漂浮於過去及未來、地方與非地方之間,王之博輓歌式的園林景色充滿歷史影響的衝擊,

也充斥著不尋常的並置及不合理的地標。

供石呈現出灰色白色的裂縫,反耀在柔和的一排排花園的景物之間:樹幹隆起而茂密粗壯

的棕櫚樹;瘦弱小樹的樹葉被剪切成鋸斷狀;小徑與發白的矮欄或扶手杆。這些樹木及小

徑佈滿整個構圖,一直後移至遠處的、帶著褐橘色條紋狀的天空下一個矮小的木屋。

因爲沒有人物的存在,王之博畫作中的地標其實十分普通,甚至平凡之至。然而,畫家的

潤飾把它們豐富起來,令觀眾投入一個奇異的冥想及思考的境界,一個異乎尋常而雜混的

自然與人造之間的狀態。當觀者的雙目凝視着王氏的畫作時,畫布上的色彩好像要跳躍出

來一樣,在不同的時刻,展示出不同的美學元素:點、線、條紋等,同時向現代及古典風

格帶來的各種影響致敬。

王氏技巧高超,有如一位鋼琴家,能輕易地演奏各類風格的樂章。畫布上塗上隨意的厚厚

油彩,刻意地產生質感,從而散發出一種愉悅的靈活性。從她的畫作中,可看出王之博對

自相矛盾的空間擁有強烈的觀察力及詮釋力,它們當中包括美麗、莊嚴、懷舊之情及黑

暗。公園這類空間好像有自己的生命力,屬於另一個世界一般。就像超現實的神話風景一

樣,大自然與奇特的、已被遺棄或變成荒野的建築共處。這些空置的地方表達了私隱的空

間,或是幻想裡藏著的内在空間,一個讓畫家遠離生活的壓力,開懷探索思維的地方。

在王之博的《 綠 色故障》裡,場景及空間都塞得滿滿的。像叢林的空間好像一半被忽略

了,雖有秩序,卻又混亂。尖禿的樹頂被切斷,與高聳而浪漫的棕櫚樹混集在一起,它

們交織的強勢駕馭擺放在院前那些峻峭的、現代仿古供石,以及橫跨畫面下方的欄杆與樹

籬。王氏的筆觸精巧靈敏,她運用的色彩及筆畫,讓畫面變得更柔和更溫暖。細緻的灰綠

色與褐橘色的天空與前面的空地對照得更加明顯。油畫下半部滿佈縱橫交錯的形狀、色彩

及光影。油彩看起來既壯麗又顯著,展現出綫條、筆畫與細節,讓觀者感覺到畫面的表

層,感受創作畫作的喜悅。天空的顔色與薄紗般的質感有著意大利風格,畫中也偶爾帶有

表現主義與後現實主義形態,但畫筆卻製造出一種相比十九世紀的馬奈或二十世紀的弗洛

伊德或霍珀軟化了的實質感。

《紅色故障》是一幀較簡潔的作品,同樣集中於表層及透視、色彩及形態的描繪。從後方

看著一棵滿佈冰霜,被兩塊巨大紅色岩石包圍著的杉樹,隱約的看到兩旁有一團葉子圍在

樹腳。這自然現象看似有點奇異及笨重。在高高的人造岩石的紅色斑點上有深黑色的割

痕。它們與狹窄邊沿的雪白表面,形成對比。這個構圖顯得富戲劇性,因爲兩組紅色岩

石及地面與蒼白的天空及可怖的樹木,正好代表著它們生命的反差,以及彼此所隔離的

空間。

王之博的輓歌式園林景色

40

在另一幀講求強烈對稱的作品《我們只是愛美景》中,兩座噴泉環繞著一幢半懷舊式酒店

的大堂中央。相對於整體的空間,噴泉的比例過大,一切都擠在一起。這個建築在四周密

佈的稜角圍牆及圓形噴泉下,似是有點過於壓倒性和多餘。

《景觀》描述公園的地面水平。那裏散佈著不少人造的建築,它們形成若干個噴泉,當中

的泉水隨意地流向前方的藍色水池。畫面上淺色的人造石塊與遠方深綠色的叢林互相補

足,讓石塊與噴泉顯得更加生動。這些表面塗上了色彩,令到像是沒有生命的景觀,在精

巧的顏色配搭下,顯得生動起來。建築與泉水都有豐富的體裁、畫法及結構。意大利風格

雕刻而成的大碗放在矮柱之上,與左面方形的木雕產生矛盾的感覺,是超現實的後現代設

計。它們的並置好像沒有任何刻意的美學或邏輯。

王之博的作品主題,是因城市發展而運生的混合式而非純粹建築的公共地方。她筆下描繪

的這些隨意而不合邏輯的非地標,在當今的中國是十分普遍。畫作的現代性與新環境產生

共鳴,脫離固有的傳統。這些公園主要爲了捕捉那些超越了都市或郊區發展與生活,但它

們也好像被淘汰,變成一無是處。

在中國,公園擁有數百年的歷史,也是現代都市規劃的重要部份。它是為現代的群眾構想

出來,供大衆休憩、家庭及社交聚會及娛樂之用。在上海及北京等城市的大型公園,週末

往往是充滿了放風箏、太極班、社交舞班、釣魚及下棋的人群。

古雅的花園是明朝最卓越的文人長成地,是高端文化裡精緻美學及哲學的空間。這些花園

内,都有供石及建築特色,如亭台樓閣與橋樑等。這些園景,在每每在詩歌中被讚揚,以

文人秀士的彩筆、墨硯及宣紙加以形容。

自二十世紀開始,公園開放給大衆,成為市民的場所,例如北京著名的北海公園。然而,

在王之博的作品中,公園就好像被超級發展的都市化、商業化及無間斷的開發所吞噬,或

是被忽略。在此情況下,它們被描繪成為奇怪的「後毛澤東」、「後現代」、甚至是「後人

類」的地方。

王之博是新一代優秀畫家的一員,她堅守著嚴格的傳統油畫法則,儘管油畫已被西方很多

同 行 所 摒 棄 。 油 畫 在 中 國 擁 有 一 個 半 世 紀 的 歷 史 , 它 的 藝 術 特 徵 , 是 現 代 化 及 大 變 革

自 相 矛 盾 的 結 果 。 繼 法 國 及 俄 羅 斯 傳 統 學 院 派 的 現 實 主 義 、 印 象 主 義 及 英 雄 式 社 會 主

義 歷 史 油 畫後,在1980年代,風景與肖像畫,因著人文主義及對農村的注意,而得以復

甦。十九世紀的法國畫家及至現代的美國現實主義畫家如安德魯 . 惠氏創作的作品,被形容為

浪漫、壯麗及富有詩意,是特別為響應上世紀意識形態的英雄主義,對單一純淨外型的描

繪。其後,人物描繪成為中國當代美術的主流特徵,不論在繪畫、攝影或表演藝術上,皆

以全體或個別英雄姿態出現,反映出與思想意識及社會階級混雜的社會上集體與個別之間

的張力。

王之博的作品與這兩個導向背道而馳。她選擇集中於人工打造的郊區風景以提供不同的哲

學觀點。這些公園或庭院既非高文化,又非普羅文化,而是一個「後消費者」、「後意

識 形 態 」 時 代 的「非 文 化 」。一 群 年 青 的 畫 家 , 包 括 王 之 博 , 顯 露 出 過 去 二 十 五 年「後

毛 澤 東 」藝 術 的 漸 趨 成 熟 , 並 經 歷 過 無 數 次 風 格 上 的 演 變 。 王 之 博 的 作 品 被 視 為 中 國

新 形 式 主 義 年 青 一 代 中 具 實 力 的 一 員 , 在 近 年 氣 勢 越 見 強 勁 。 在 她 的 畫 作 中 , 自 然 主

義 、 後 寫 實 主 義 、 新 表現主義的元素完美地結合在一起,把一切自然與人為物質也包括

在內。計劃生育孕育出來的獨生子女一代帶來的,是自省的氛圍。王之博的作品讓別處得

41

以活起來。這些安詳的靜物風景畫,正如布賴森探討這個題目的文章道,“ 把目光投在被

忽略的那些”1,提醒我們多留意那些瑣細的、近距離的事物。

1 諾曼·布賴森,《把目光投在被忽略的那些:

靜物畫四講》,Reaktion Books, 2004。

凱蒂 . 希爾博士於專門研究當代中國藝術方面擁有相當豐

富的經驗,現為倫敦蘇富比藝術學院的東亞藝術課程擔

任客座講師。她亦身兼中國當代藝術辦公室(OCCA)的

總監,致力在英國推廣和展示中國藝術家。她曾於2010

年在英國泰特現代藝術館與艾未未進行現場對話,亦為

多本有關當代中國藝術的書藉寫作,包括《藝術轉變:

中國新方向(Art of Change: New Direction from China) 》

(Hayward Gallery出版) 、《中國藝術(The Chinese Art

Book) 》(Phaidon出版)等。

43

The Elegiac Parkscapes of Wang Zhibo

By Dr. Katie Hill

Caught in a state of suspension between past and future, place and non-place, the

elegiac parkscapes of Wang Zhibo depict sceneries of colliding historical influences

filled with unnatural juxtapositions and illogical geographies.

A cluster of scholar’s rocks display shining, creviced surfaces in greys and whites,

glistening in a soft light amongst a strange array of other garden features: a towering

palm with sweeping leaves and a long ridged trunk; thin brittle trees with their

upper branches clipped off leaving jagged spikes; pathways and whitish low railings or

balustrades. These plants and walkways are densely layered within the composition,

receding into the distance towards a deeply streaked brownish-orange sky above a

low-lying wooden building.

Devoid of human presence, the places in Wang Zhibo’s paintings are unspectacular,

even ordinary. Yet, their painterly transformation lends a rich quality that lifts them

into almost magical spaces of meditation and speculation drawing us into a bizarre

hotchpotch of nature and artifice. In viewing her paintings, the eye moves across the

canvas taking in the dense composition, as paint leaps out at us in multiple aesthetic

references: dots, lines, streaks, at different moments, pay homage to both modernity

and classicism plucked from an array of possible influences.

Wang’s work is technically virtuoso, using her skill like that of a pianist with a broad

repertoire who can play all styles and notes easily. The thick surface of the paint is

deliberately textural and freely applied, communicating a joyful sense of its versatility.

The paintings bear witness to Wang’s close observation and interpretation of

paradoxical spaces that she imbues with beauty and dignity, nostalgia and darkness.

Public gardens or parks evoke places with lives of their own, existing as worlds apart.

Like surreal, fairytale landscapes, nature cohabits with odd architectural features that

appear abandoned or deserted. The emptiness of these spaces also conveys a space

of privacy, an inner or interior space of the imagination, where the artist can explore

and play with her imagination and material away from the pressures of life.

In Green Fault, the space of the scenery is clustered and busy, a jungle of a space

created yet half neglected, ordered yet chaotic. Spiky leafless trees cut off at the top

mingle with tall, romantic palms; these loom majestically over the craggy rocks in the

foreground that are modern, artificial versions of traditional scholar’s rocks from the

Chinese tradition and low balustrades and box hedges cut across the lower plane.

Wang’s brush transforms the scene through exquisitely sensitive use of colour and

44

brush, softening and warming the picture into a rich scene. Subtle green-greys are set

off by the orangey-brown sky and patch of ground at the foot of the picture, which

is filled with a complex zigzagging of forms, colours and interplay of light and shade.

Paint is gloriously apparent, revealing itself in so many lines, strokes and detailed

descriptions, drawing us into the picture and leading us through its surface to feel the

enjoyment of its making. There is an Italianate sensibility in the colour and thinness of

the sky, expressionist moments and post-realist depictions of form, with solidity that

is softened and highlighted as painterly gesture from, say, a nineteenth century Manet,

or a twentieth century Freud or Hopper.

Red Fault is a more pared down work that also plays with surface and perspective,

colour and form. A narrow view of a huge dense fir tree tinged with frost is narrowly

framed by two enormous reddish rocks seen from the back looming on each side,

with a ring of small foliage dotted at their feet. The nature in this scene appears

bizarre and cumbersome. There is a strange quality to the red-flecked surface of the

tall artificial rocks with slashes darkly cut into them, contrasting with the iced white

surface of the narrow side. The composition is dramatised into two distinct spheres

of red rocks and ground, set against a freezing pale sky and ghostly tree, distancing the

life of the rocks from that of the trees, spatially cutting them off from each other.

In another painting of strong symmetry, We just love the beauty, two fountains flank

a structure in the centre within a semi-interior reminiscent of a hotel foyer that

appears too clustered and large scale for the space available to it. The architecture of

this space seems overbearing in its crowded placing of angular walls, fountain-features

and a circular, fenced off area that is central yet superfluous.

Spectacle is filled with the park’s ground level, sprawled with manmade structures

making up an elaborate yet bland water feature of several shallow fountains flowing

feebly into a low bluish pool in the foreground. The scene of pale, artificial stone is

offset in the distance by a thick wall of trees and foliage in deep greens, relieving

the paleness of the light stone and fountains. The surfaces are painted so that

the potentially lifeless scene is lit up and varied in its subtle blend of colours and

movements, as architecture and water are vividly portrayed in a rich array of forms,

perspectives and textures. The Italian-style carved bowls set on top of broad, low

columns, contrast with the angular wooden structures to the left, another public

garden feature, in a surreal mélange of postmodern design, created with no apparent

aesthetic integrity or logic.

Modern architecture of a hybrid, bastardised kind is a central feature of the works,

made for public places within urban development. These non-places, sumptuously

depicted in Wang’s works, are suggestive of locations created in a haphazard

craziness of illogical design characteristic of contemporary China. The modernity of

the paintings is resonant of new environments, cut off from traditional allegiances.

Primarily descriptive of life in areas of development that exist beyond the ‘urban’ or

‘suburban’, even these parks seem to have become obsolete, useless.

45

In China, public parks are a vital part of the urban landscape and date back centuries,

conceived in the modern period for ‘the masses’, spaces for leisure, family and social

gatherings, and entertainment. The large parks in cities such as Shanghai and Beijing

are packed at weekends with huge numbers of people, flying kites, practising T’ai Chi,

ballroom dancing, fishing for goldfish and playing Chinese chess.

Classical gardens were an aspect of elite literati culture that flourished during the

Ming dynasty, created as sophisticated aesthetic and philosophical spaces of high

culture, incorporating rocks and architectural features such as roofed pavilions and

fine bridges. These were appreciated in the poetic tradition, to complement the

literati scholar’s tools of brush, ink-stone, carved ink-sticks and fine xuan paper.

In the modern period, since early twentieth century, public parks were opened up as

civic spaces, such as the famous Beihai Park in Beijing. In Wang’s works, however, the

gardens appear to be tucked away or neglected as superfluous leftovers in a world

of super-rapid urbanisation, commercialism and constant unremitting development. In

this context, they are depicted as possible retreats, strange, mixed-up locations that

are post-Mao, postmodern, even post-human.

Wang is a part of the new generation of superb painters emerging within this new

landscape, adhering to the highly disciplined tradition of painting in oil on canvas that

has now been partially abandoned in the West. Following its history of a century

and a half, oil painting is one of China’s great artistic attributes as a paradoxical

result of its modernisation and revolution. After the French and Russian traditions of

academic realism, impressionism, and epic socialist history paintings, both landscape

and figurative painting revived in the 1980s with the rise of humanism and attention

to the rural. Landscapes drawn from French nineteenth century painters and modern

realist American painters such as Andrew Wyeth, were depicted as romantic, epic and

poetic featuring single innocent figures painted in response to the previous decades of

ideological heroism. Figures later became a predominant feature in contemporary art

from China, in paintings, photography and performance presented either en masse or

as single heroes, reflecting the tension between the collective and the individual in a

society interwoven with competing ideologies and economic classes.

Wang’s paintings depart from these two trends, preferring to focus on the artificial

suburban landscape to suggest a different philosophical perspective. These parks

or gardens are neither high culture, nor mass culture but perhaps non-culture in

a post-consumer, post-ideological age. Younger painters, including Wang, reveal a

maturing of the medium over a twenty-five year period of the post-Mao era that

has already undergone numerous stylistic evolutions. Her paintings can be seen as

part of a strong trend of new formalism in young painting in China, that has gained

momentum in recent years. In her work, elements of naturalism, post-realism and

neo-expressionism merge and come together seamlessly in a celebration of form and

an embrace of the materiality of existence across the natural and the unnatural. The

single-child generations of artists have produced an introspective mood. Wang’s works

breathe life into an elsewhere. As quiet still life landscapes, after Bryson’s essays on

46

still life painting, they ‘look at the overlooked’1 reminding us of the more minute,

close-up experience of China away from its spectacular, external image, that might

otherwise remain unseen or ignored.

1 Norman Bryson, Looking at the

Overlooked. Four Essays on Still Life

Painting, Reaktion Books, 2004.

Dr. Katie Hill has extensive experience in the field of contemporary Chinese art. She is a lecturer for the MA in East Asian Art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art, London, and is a regularly invited guest lecturer. Her recent work includes, ‘In Conversation’ with Ai Wei Wei, Tate Modern, selector panel/author, Art of Change: New Direction from China, Hayward Gallery, London and specialist advisor/author for The Chinese Art Book, Phaidon. Katie Hill is director of OCCA, Office of Contemporary Chinese Art, an art consultancy promoting Chinese artists in the UK.

49

《石頭》Stones

2012 油彩 畫布 Oil on canvas200 x 250 cm

51

《無題(泉)》Untitled (Springs)

2012 油彩 畫布 Oil on canvas112.5 x 150 cm

52

《紅色故障》Red Fault

2012 油彩 畫布 Oil on canvas130 x 92 cm

54

《無題(泉II)》Untitled (Springs II)

2012 油彩 畫布 Oil on canvas151 x 180 cm

《景觀》Spectacle

2012 油彩 畫布 Oil on canvas150 x 180 cm

58

《綠色故障》Green Fault

2012 油彩 畫布 Oil on canvas157 x 180 cm

60

《陪音》Overtone

2012 油彩 畫布 Oil on canvas84.5 x 121 cm

61

62

《無題(節日)》Untitled (Festival)

2012 油彩 畫布 Oil on canvas137 x 180 cm

63

64

1981年生於中國浙江省現於杭州生活及工作

學歷

2005-2008中國美術學院第四工作室研究生

2005畢業於中國美術學院油畫系

參展

2013 「駐波」馬凌畫廊 香港 中國2013 紐 約 軍 械 庫 藝 博 會 紐約 美國

2012 「2012青年藝術家扶持推廣計劃彙報展」北京國際會展中心 中國「虛構的復原」上海對比窗畫廊 中國

2010「改造歷史」— 2000-2009年的中國新藝術 北京阿拉裡奧畫廊 中國

2009「講述 — 2009」海峽兩岸當代藝術展 台灣美術館; 北京中國美術館 中國「果凍在安特衛普」比利時安特衛普美術館 比利時「羅中立獎學金獲獎作品展」北京大學百年講壇 中國「刀鋒 — 重建雷峰塔」北京聖之空間 中國

2008「幽塘與浮標」當代藝術展 南京青和美術館 中國「未來的天空」中國當代青年藝術家邀請展 北京今日美術館 中國「2008 羅中立獎學金獲獎作品展」重慶美術館 中國「果凍在台北」台北當代藝術館 台灣「08 新視覺」深圳何香凝美術館 中國

2007「果凍時代當代藝術展」上海美術館 中國「China Today」當代藝術展 Bartha & Senarclens 畫廊 日內瓦 瑞士

2005第二屆成都雙年展 成都現代藝術館 中國

王之博

65

Born in Zhejiang Province in 1981 Works and lives in Hangzhou

EDUCATION

2005-2008MFA, China Academy of Art Oil Painting Department

2005BFA, China Academy of Art Oil Painting Department

EXHIBITIONS

2013Standing Wave, Hong Kong, China The Armory Show 2013, New York, United States

20122012 China Young Artists Exhibition Project, Beijing International Convention and Exhibition Center, Beijing, ChinaFictional Recoveries, Pearl Lam Fine Art, Shanghai, China

2010Reshaping History: Chinart from 2000 to 2009, Arario Gallery, Beijing, China

2009Narrate—The Contemporary Art Exhibition on both sides of Taiwan Strait, National Taiwan Museum of Fine Art, Taiwan/ The National Art Museum of China, Beijing, ChinaInfantization. The New Power of Chinese Contemporary Art, FotoMuseum, Antwerp, BelgiumLuo Zhongli Scholarship Exhibition, Peking University, Centennial Hall, Beijing, ChinaBlade—Rebuild the Pagoda, SZ Space, Beijing, China

2008Deep Pond and Float Chamber, Nanjing Qinghe Contemporary Art Museum, Nanjing, ChinaFuture Sky - Chinese Contemporary Young Artist Invitation Exhibition, Today Art Museum, Beijing, ChinaLuo Zhongli Scholarship Exhibition, Chong Qing Art Museum, Chong Qing, ChinaInfantization, Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei, TaiwanNew View, He Xiangning Art Museum, Shenzhen, China

2007 Infantization, Shanghai Art Museum, Shanghai, ChinaChina Today, Bartha & Senarclens Gallery, Geneva, Switzerland

2005The 2nd Chengdu Biennial Exhibition, Chengdu Modern Art Museum, China

Wang Zhibo

鳴謝

展覽刊物

王之博 | 駐波香港馬凌畫廊 2013年2月22日至25日

紐約軍械庫藝博會 2013年3月7日至10日

2013年馬凌畫廊出版

巨浪高企的靜止 柯提斯 .卡特博士著

王之博的輓歌式園林景色 何凱特博士著

中文翻譯:李正欣 (繆思坊有限公司)

設計:謝敏生

承印:利高印刷有限公司 (中國香港)

ISBN: 978-988-16827-3-4

馬凌畫廊

香港中環皇后大道中8號1樓T: +852 2810 0317 www.edouardmalingue.com

Acknowledgements

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

Wang Zhibo | Standing WaveHong Kong 22-25 February, 2013

The Armory Show, NY 7-10 March, 2013

Publication © 2013 Edouard Malingue Gallery

Standing Wave © Dr. Curtis L. Carter

The Elegiac Parkscapes of Wang Zhibo © Dr. Katie Hill

Chinese translation by Joanna Lee (Museworks Limited)

Design by Olivia Tse

Printing by Regal Printing Limited, Hong Kong

ISBN: 978-988-16827-3-4

First Floor 8 Queen’s Road Central Hong Kong T: +852 2810 0317 www.edouardmalingue.com