UAWANUI-A-RUAMATUA

-

Upload

sam-sadlier -

Category

Documents

-

view

262 -

download

5

description

Transcript of UAWANUI-A-RUAMATUA

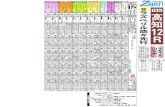

26 • TE AO MAORI MAI I TE TAIRAWHITI • FRIDAY, DECEMBER 7, 2007

He Mihi

NGĀ MAUNGA

Ko Tītīrangi te maungaTītīrangi is the mountain

Ko Ūawa te awaŪawa is the river

Ko Te Āitanga-a-Hauiti te iwiTe Āitanga-a-Hauiti is the tribe

Ko Te Kani-a-Takirau te tangataTe Kani-a-Takirau is the chief

Tīhe mauri ora!Alas the breath of life!

APPROACHING Ūawa (Tolaga Bay) by the main road from the south, you cannot miss the mountain ridge of

Tītīrangi. Looking to your right, it emerges from the land like a colossus, prominently positioned and sheltering the inland flats from the ravages of wind and sea. From its summit one can survey the beauty of the surrounding landscape and a breathtaking view of the ocean. Tītīrangi, like all the maunga (mountain) featured in this series, has stood witness to all that has happened in and around its location. The stories that follow are but

a smattering of the events that Tītīrangi has seen, but such has been their impact that the lives of the people of the area have changed forever. Witness, for instance, the proliferation of the arts under Hīngāngāroa and the whare wānanga (school of learning) of Te Rāwheoro; the emergence of Hauiti over his older brothers, Taua and Māhaki, to claim mana whenua (right to land) of Ūawa and its surrounds; the arrival of Captain James Cook at Te Ūpoko-o-te-Ika (Cooks Cove) in 1769; and the life of perhaps the last paramount chief of Te Tairāwhiti, Te Kani-a-Takirau. Add to these the story of Ruakapanga and his prized birds and how kumara was brought to the region, Tītīrangi has seen it all!

The people of Ūawa (full name, Ūawanui-a-Ruamatua) and Te Āitanga-a-Hauiti fiercely protect the traditions and practices of their ancestors. From the time of Hauiti, the occupation of their lands has been continuous and undisputed. The manifestation of these traditions has evolved into presentations such as Te Pou o Te Kani, Ūawanui, Rūawa and countless other activities in the name of the arts and academia. Little doubt indeed that things are really happening in Ūawa, and all under the discerning eye of Tītīrangi. Does Ūawa rock? You bet!

KO te mihi whānui ki a koutou i tēnei putanga, te ngahuru hoki o ngā tuhituhi e kōrerohia nei ko, Ngā

Maunga Kōrero o Te Tairāwhiti. Kua whakatata pēnei mai mātau ki roto o te tarawāhi e mōhiotia whānuitia ko Ūawa me tōnā maunga teitei rawa, ko Tītīrangi. Kauaka e pōhēhē ki te Tītīrangi o Tūranganui-a-Kiwa nei, he Tītīrangi kē tēnei. Ā, me ngā kōrero e hora nei, mō Ruakapanga me āna manu nui, mō Hīngāngāroa me tana tama a Hauiti, mo te taenga mai o iwi kē, me te rangatira rongonui, a Te Kani-a-Takirau. Anō nei rā, tangatanga mai, pānui mai, whakaarohia mai.

A warm greeting to you all and to this the tenth issue of the series Ngā Maunga Kōrero o Te Tairāwhiti. From Whareponga in the last issue, we’ve come back towards Gisborne to Ūawa (Tolaga Bay) and their mountain, Tītīrangi — not to be confused with Tītīrangi in Gisborne.

We will cover the stories of Ruakapanga and his birds, of the artisan Hīngāngāroa and his son Hauiti, the eponymous ancestor of the tribe that bears his name, the contact with Captain James Cook, and the story of the paramount chief Te Kani-a-Takirau. Once again, relax, read and let your thoughts wander.

Kahutia — Department of Māori Studies & Social Sciences, Tairāwhiti Polytechnic

Please note: Photographs of Ruapakanga Marae together with the carvings and the image of Te Kani-a-Takirau shown on these pages cannot be used for any other purpose without the permission of the Hauiti Ruakapanga Marae Trustees.(A special thanks to Wayne Ngata, Victor Walker, Māui Tangohau, Adrian Stewart, Cynthia McCann and the Hauiti Ruakapanga Marae Trustees — he mihi nui ki a koutou katoa)

Me ko Manutangirua ko HīngāngāroaFrom Manutangirua descends Hīngāngāroa

Ka tū tōna whare Te Rāwheoro eWho built his house of learning Te Rāwheoro

Ka tipu te whaihanga, e hika, ki ŪawaProliferating the arts from Ūawa

Hīngāngāroa stands as one of the most important ancestors of the people of Ūawa. He was, after all, the father

of Hauiti, the eponymous ancestor of the Te Āitanga-a-Hauiti tribe. And in his day, he was renowned for his reputation as a tohunga (expert) of the arts and ancient traditions.

Hīngāngāroa was born about 1550. He was the son of Manutangirua and Kehutikoparae. His whakapapa (genealogy) connected him to all the principal senior ancestral lines of Te Tairāwhiti. His marriage to Iranui further reinforced these lines and gave him a brother-in-law in Kahungunu and a daughter-in-law, Kahukura-iti (wife of his son Hauiti), who was the daughter of Rongowhakaata and Moetai. Another daughter-in-law, Rākau-manawa-hē — the junior wife of Hauiti — was also the daughter of the chieftainess Uepōhatu.

Hīngāngāroa was a skilled artisan, a tohunga of whakairo (wood carving), and a builder of waka (canoe). His reputation was such that his brother -in-law Kahungunu, then resident in Maungakāhia pā on the Māhia Peninsula, requested if he could build him a waka. The task was a mere formality for the talented Hīngāngāroa, but easier said than done when you possess the skill, the knowledge and associated rituals and karakia (incantation) to go along with it. This is what Hīngāngāroa had. In today’s parlance we would say he was “the real deal”.

The knowledge and skill that Hīngāngāroa possessed ult imately culminated in the development of the whare wānanga (house of learning) Te Rāwheoro. This wānanga was to become the leading centre of the arts and associated knowledge of Te Tairāwhiti, extending all the way to the Wairarapa. This knowledge

traced a line of descent going back to Tangaroa, from whom the origin of all art forms — whakairo (carving), tāmoko (tattoo) and raranga (weaving) — can be sourced. This knowledge was passed down to Uenuku, the feared but revered high priest of Hawaiki, and his senior wife Rangatoro, on to their son Kahutia-te-rangi, who married Hauwhakatūria, then to their son Rongomai-tū-aho. Rongomai-tū-aho became the leading priest of these ancient traditions and set up the whare wānanga named Te Aho-matariki at Whāngārā. Seven or so generations forward, his descendant Hīngāngāroa established Te Rāwheoro in Ūawa.

Te Rāwheoro flourished for many centuries and produced many tohunga in the art forms, knowledge and traditions of the ancestors originating from Hawaiki. The proliferation of whakairo entrenched itself into a carving style distinctively that of the Te Rāwheoro school. Even Captain James Cook commented, in 1769, on the state of the arts in Ūawa, evidenced by the elaborately carved meeting houses and pātaka (store houses) he and his crew saw. Te Rāwheoro closed in the mid 1800s, its last tutor and priest being Rangiuia. Included amongst its last students were Mohi Ruatapu of Tokomaru Bay, and Tokipuanga and Hoani Te Parehuia of Ngāti Ira.

Te Rāwheoro may be gone but the tradition of the arts, originated by Hīngāngāroa, continues to flourish among his present day descendants.

Hīngāngāroa and Te Rāwheoro

Looking south across the bay from Tātarahake, the setting sun strikes Tītīrangi.

Tītīrangi and Ūawa

HAUITI, the eponymous ancestor of Te Āitanga-a-Hauiti and the people of Ūawa, was the youngest of

the three sons of Hīngāngāroa and Iranui. His rise to leadership was a classic story of brother versus brother, young versus old, and conquest against the odds. Hauiti was born about 1575 but generally lived in the shadow of his older brothers, Taua-i-te-rangi and Māhaki-ewe-karoro. As tradition would dictate, the mana of their father, Hīngāngāroa, would ultimately pass on to the sons — in particular the oldest son.

As they grew older the story is told of how the three brothers turned their attention to fishing. With their attendants and followers they all made kaharoa (large seine fishing nets) for themselves. Hauiti named his net Whakapaupakihi; whakapau meaning to consume or to take all and pakihi meaning the ebbing tide — an obvious reference that he would catch all the fish in the changing tide. One day all the brothers, with their followers, went to sea to trial their new nets. When they returned, Hauiti’s net contained a great deal more fish than those of his brothers. Taua and Māhaki, envious at being upstaged by their younger brother, forcibly helped themselves to the best fish in Hauiti’s net. This happened not once but several times, and all the while Hauiti was wondering how he could circumvent the behaviour of his elder brothers.

Hauiti therefore went to see a tohunga named Marukākoa of the Ngā Ariki tribe, who lived in a place called Makihoi, near the present township of Matawai. Marukākoa could be compared to the modern day life coach, but with a bit more bite to his teachings. He instructed Hauiti in several methods of how to deal with his unreasonable brothers. After a short period under Marukākoa’s tutelage, Hauitireturned home to his pā at Te Rāroa, on the Tītīrangi ridgeline, and prepared his followers for the task ahead.

As he had done many times in the past, Hauiti and his people cast their nets into the sea. Like before, his net brimmed with kahawai (fish). And again, like before, Taua and Māhaki’s followers came down to the beach to take their share of the catch. This time, though, Hauiti signalled his people to retaliate and in their shock and haste to retreat, the marauding hordes of Taua and Māhaki dropped their bundles of kahawai and scurried back to the safety of their homes. The battle was called “Te Kahawai Makere — the dropped Kahawai”. But the brothers had not learned their lesson and a following fishing expedition met with the same response. Hauiti commanded his

people to raise the ends of the net and envelop all the marauders within it. This time they were mercilessly slaughtered and the battle was named, “Te Kaha Whitia — The joined ends”.

Taua and Māhaki realised their younger brother meant business and they assembled a war party to destroy him. Hopelessly outnumbered (some sources say 300 against 2000), Hauiti commanded his people to assemble their belongings and leave their homes for a safer place. They travelled in the night but by morning were overtaken by Taua and Māhaki’s warriors. In the ensuing battle both sides suffered heavy losses and Hauiti was speared in the leg, but still emerged victorious. The battle was called Te Werewere. Several more battles followed and were given the names Tā-wehi-kura, Kauneke, Ngaru-e-nuku, Rangihīwera and Parawera-nui. By the end Hauiti had overcome his brothers and banished them forever to the fringes of the tribal territory.

Despite this, however, Hauiti still needed to consolidate his position as the principal heir of their father’s estate. His brothers and their followers till constituted a threat, and with his advancing age he passed the mantel of control on to his eldest son, Kahukuranui. Through a number of battles, Kahukuranui completed the expulsion of the progeny of Taua and Māhaki. Taua’s granddaughter, Rongomai-huatahi, took refuge in Te Kaha and from her son, Apanui-ringa-mutu, originated the tribe of Te Whānau-a-Apanui. Māhaki’s family moved north into the Waiapu Valley, consolidating what is recognised as Ngāti Porou Tūturu. Thus Hauiti, through his children and in particular his son, Kahukuranui, affirmed the tribal region we now recognise as Te Āitanga-a-Hauiti, stretching from Ūawa all the way to Gisborne.

Te Āitanga-a-Hauiti – The Descendants of Hauiti

The sons of Hīngāngāroa and Iranui, Taua (left), Māhaki (centre) and Hauiti (right). The carvings are all part of a single pou (carved post), with Taua above, Māhaki in the centre and Hauiti at the bottom.

IranuiHīngāngāroa

Ūawa-nui-a-Ruamatua, looking north to the Ūawa River (centre). Pāoneone, the pā of Taua and Māhaki, was on the inland part of the ridgeline at the far end of the bay. The ridge also comprised Tātarahake going seaward and then Pīrau at the seaward end. Hauiti at this time resided on the southern side of the river.

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI • FRIDAY, DECEMBER 7, 2007 • 27

KŌRERO O TE TAIRĀWHITI

Ngā Manu nui a Ruakapanga – Ruakapanga’s Prized Birds

Ko Ruakapanga te huinga o te iwiTis Ruakapanga who unifies the people

Te tipuna o te whare nei e!Tis he the ancestor of this house!

RUAKAPANGA is the name of the whare whakairo (carved meeting house) at Hauiti Marae. Hauiti Marae

is just off the main road approaching Tolaga Bay from the south. Ruakapanga was a descendant of Rūaumoko — the earthquake God and the guardian of the art form of tāmoko — and lived in far away Hawaiki. He owned two great birds, known by the names Hāro-ngā-rangi and Tiu-ngā-rangi, and was also a tohunga (expert) in the cultivation of kumara. Ruakapanga, together with his birds, is credited with introducing the kumara to Te Tairāwhiti and their story is indelibly etched

into the traditions of the Ūawa region. Many of you are familiar with the story of Kupe

and his discovery of Aotearoa, a name supposedly uttered by his wife when describing the land that suddenly appeared before them covered by a “long (roa), white (tea) cloud (ao)”. Some writings date this journey to about 925AD while other sources say 1400AD. When Kupe eventually returned to Hawaiki and spoke of his journey, Ruakapanga decided to look into the possibility of cultivating kumara in this far-off land. With that in mind, he sent one of his protégés, Tairangahue, to investigate.

Tairangahue and a crew of helpers, who included Pourangahua and his wife Kanioro, set sail for Aotearoa and made landfall in Tūranga (Gisborne). They were greeted by the sound of singing birds — the shining cuckoo, the fantail, the kiwi and the weka — and the splendour of blossoming kōwhai trees. Spring was in the air and Tairangahue also assessed that the soil was well suited to the growing of kumara. He and Pourangahua immediately sailed back to Hawaiki to tell Ruakapanga, leaving behind Kanioro and others of his crew in Tūranga. Once home, he reported to Raukapanga all that he had seen and heard, and that the land on the eastern seaboard would be an excellent place to grow kumara.

Ruakapanga agreed and ordered Pourangahua to return to Aotearoa immediately with the kumara tubers in order to catch what remained of the planting season. Ruakapanga entrusted his prized birds, Hāro-ngā-rangi and Tiu-ngā-rangi, to Pourangahua’s care to hasten his return to Aotearoa. He also gave some equipment to take

with him — two kete (kits) named Hou-tākere-nuku and Hou-tākere-rangi, which contained the kumara tubers, and two kō (digging implements) named Mamae-nuku and Mamae-rangi. Pourangahua was to fly on Hāro-ngā-rangi while the kete, with the kumara tubers, and the kō would be carried by Tiu-ngā-rangi.

Ruakapanga gave Pourangahua str ict instructions as to the treatment of the birds. “Do not fly near Hikurangi lest Tama-i-waho (taniwhā — goblin) snares you for his dinner. And what ever you do, do not pull out any of the feathers.” He was also given incantations to perform on the birds when they arrived in Tūranga and for their safe return home. Simple enough, Pourangahua thought, and off he flew on the prized birds of Ruakapanga.

As Pourangahua neared the northern coastal reaches of Te Tairāwhiti, so excited was he at the prospect of seeing his wife, Kanioro, that he totally forgot about Ruakapanga’s instructions. To shorten his journey he flew over Hikurangi and was attacked by Tama-i-waho. He was lucky to survive this attack but the birds were the worse for it. As he neared Tūranga the birds circled around looking for a suitable place to land. But Pourangahua became impatient and pulled out one of Hāro-ngā-rangi’s feathers to hasten his descent. When they finally did land Pourangahua greeted his wife and his comrades, forgetting

about the birds until he heard their cries. He was overcome with shame and hastily chanted the karakia (incantations) that Ruakapanga had given him for their safe return to Hawaiki.

The journey home wasn’t without drama, for the birds were set upon by the spirit guardians, Tū-nui-o-te-ika and Hua-taketake. By the time they arrived back to their master they were completely exhausted and in a state of collapse. Ruakapanga was furious. To avenge the maltreatment of his prized birds, he dispatched three pests that would forever blight the kumara of Pourangahua — the anuhe to eat the buds, the mokoroa to eat the shoots and the mokowhiti to eat the leaves. To this day, these grubs continue to ravage kumara crops throughout Aotearoa, reminding us of Pourangahua’s neglect of Ruakapanga’s birds.

Another aspect of this story is that thefeather pulled by Pourangahua, which was cast into the ocean, took root on Toka-ahuru, more commonly known as Aerial Reef, a fishing spot near Tatapōuri. There it grew into a makauri tree and bloomed in all respects similar to those that grow on shore.

There are tribal variations to this story but all are consistent with the fact that Ruakapanga, his prized birds and Pourangahua were responsible for bringing the kumara to Aotearoa.Ruakapanga — the meeting house at Hauiti

Marae.

The pare (door lintel) of the meeting house shows Ruakapanga flanked by his prized birds, Hāro-ngā-rangi and Tiu-ngā-rangi.

ON October 23rd 1769, Captain James Cook, aboard the HMS Bark Endeavour, landed at Te Upoko o te

Ika (Cooks Cove) near Ūawa. They had already spent three days at nearby Anaura but turned back to Ūawa because of difficulty trying to land in the pounding surf, prolonging their efforts to restock their ship with water and wood. The cove was more sheltered and it was easier to get ashore. Cook and his men were warmly greeted by the locals, especially after their disastrous encounter with the people of Tūranga some two weeks before. Perhaps word had got to the people of Ūawa and they were more prepared to receive these strangers from afar.

Cook and his crew spent six days in the cove, replenishing their water and wood supply, and bartering with the local iwi for food, in particular fish. The stopover also enabled the scientific party, comprising botanist Joseph Banks and natural historian Daniel Solander, to explore the local interior, collecting plant and tree specimens and observing the lifestyle of the local people. Meanwhile, artists Sydney Parkinson and Herman Sporing sketched detail drawings of some of the things they saw. From these observations we can get an idea of what life was like back in that time.

Joseph Banks observed that many of the houses

in the valley were deserted and that most of the people lived on the ridges in, “Very slight built houses, or rather, sheds. For what reason they have left the vallies, we can only guess, maybe for air”. A strange observation indeed, when logic would suggest that retreating to the hills would be a cautionary measure with the approach of strangers. Banks described, “Cultivations were far numerous and larger than we saw them any where else and they had a far greater quantity of fine boats, fine clothes, fine carved work. In short the people were far more numerous than any others we saw.” Banks also spoke of an, “extraordinary

natural curiosity”. He said, “In pursuing a valley bounded on each side by steep hills we on a sudden saw a most noble arch or cavern through the face of a rock leading directly to the sea . . . .It was certainly the most magnificent surprise I have ever met with, so much is pure nature superior to art in these cases.” The arch cavern he was referring to is known by the name “Te Kōtore-o-te-Whenua – The rectum of the earth”, and can still be clearly seen today.

Also among Cook’s crew was a man called Tūpaea who boarded the Endeavour when it was in Tahiti in the three months prior to sailing to New Zealand. Tūpaea became a translator for Cook and, from his initial encounters with Māori in Tūranga, found that the language of Māori

was similar to his own Tahitian language and therefore could easily converse with the locals. It was during an exchange of dialogue between Cook and the local Hauiti people, via Tupaea, that a misunderstanding regarding the name of the district occurred. As a result, Cook mistakenly thought the name to be Tolaga.

The legacy of Cook’s visit to Ūawa has been enshrined in local place names — Cooks Cove (Te Ūpoko-o-te-Ika) and Sporing Island (Pourewa), and street names in the township — Cook, Banks, Solander, Parkinson, Endeavour and Gore. Also named are the ships of his second voyage, Resolution and Adventure, and from his third voyage, Discovery, although Cook himself did not return to Ūawa in either of these voyages.

IT could be argued that Te Kani-a-Takirau was the last in the line of paramount chiefs of the Tairāwhiti region. His nobility

could not be disputed, being descended from the most senior genealogical lines of the Tairāwhiti tribes, and the grandson of Hinematioro and Te Whakatātare-o-te-rangi. Te Kani was born around 1800 and belonged to Te Āitanga-a-Hauiti. He lived most of his life at Ūawa.

Joseph Baker, son of missionary Reverend Charles Baker, who was stationed in Ūawa from 1843 to 1851, described Te Kani as follows. “He was a man of princely appearance, tall, fair and handsome, with curly auburn hair and possessing all the qualities of nature’s gentleman. Being a man of extra high birth, he was looked upon as sacred by his people who numbered from Cook Strait in one direction to the extremity of the Bay of Plenty on the other side, whom he could sway in any direction by a word or wave of his hand.”

Another visitor to the area, J.W. Stack, said of him, “The man himself was quite different from anyone else I had ever seen. He possessed such an indescribable air of distinction that I felt quiet awe-struck in his presence.”

Te Kani did not mix that much with the ordinary person and generally lived by himself with minders of high rank to wait upon him. Like his grandmother, Hinematioro, he was considered to be tapu and somewhat untouchable. When he travelled he was always accompanied by a guard of honour. But he was well regarded for his generosity and was friendly towards European traders, whom he encouraged to engage in doing business with Māori. He also protected the mission station established in Ūawa under Rev. Charles Baker, but never himself became a Christian. A reason given for this is because he had a number of wives, as many as 10 according to some accounts.

Te Kani was present when the missionaryWilliam Williams visited Ūawa in May 1840seeking signatures for the Treaty of Waitangi, buthe did not sign. And when he was offered theleadership of the Kingitanga in the Waikato in theearly 1850s, he declined with the words, “Ehara taku maunga a Hikurangi he maunga nekeneke,he maunga tū tonu — My mountain Hikurangi does not move, it remains firm and steadfast.” In essence, he, like his mountain Hikurangi, was nota wanderer, unlike other mountains of Aotearoa that chased opportunities as they came along. And also, why should he, when he was already a king amongst his own people.

After a long illness, Te Kani-a-Takirau died inWhāngārā about 1856 and is said to be buried inTe Ana-a-Paikea on the island Toka-a-rangi, nearhis grandmother Hinematioro. Although he had two children, one a son named Te Waikari, bothdied before him without leaving issue.

Captain James Cook Visits Ūawa

Te Ūpoko-o-te-Ika, or Cooks Cove, where Captain James Cook and his crew replenished theEndeavour with water, wood, fish and vegetables.

Te Kōtore-o-te-whenua looking north to Tātarahake.

Te Kani-a-Takirau – Last of The Line?

Te Kani-a-Takirau.