Te Rangipureora

-

Upload

sam-sadlier -

Category

Documents

-

view

246 -

download

10

description

Transcript of Te Rangipureora

26 • TE AO MAORI MAI I TE TAIRAWHITI • FRIDAY, DECEMBER 5, 2008

NGĀ MAUNGA

Ko Ō-manu-huruhuru te maungaŌ-manu-huruhuru is the mountain

Ko Waikirikiri te awaWaikirikiri is the river

Ko Te Whānau-a-Te-Rangi-pure-ora te hapūTe Whānau-a-Te-Rangi-pure-ora is the sub-tribe

Ko Te Āitanga-a-Hauiti te iwiTe Āitanga-a-Hauiti is the tribe

Tihe mauri ora!Alas, the breath of life!

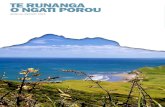

AT first sight the name Ō-manu-huruhuru is unlikely to ring a bell with the great majority

of readers. On the other hand, the photograph of Ō-manu-huruhuru might be a bit more familiar but likely to prompt the question, “I know I’ve seen it, but where?” Well, for the many hundreds and thousands of people who have flocked to the Tolaga Bay Beach Races at Kaiaua in summers gone by, it just might start to trigger the memory banks. You see, as you come in to view of the sea at Kaiaua and look right to the point, there it is, Ō-manu-huruhuru, the ancestral mountain of Te Whānau-a-Te-Rangi-pure-ora, a hapū (sub-tribe) of Te Āitanga-a-Hauiti.

In fact, our journey this month takes us into the heartland of Ō-manu-huruhuru and Te Rangi-pure-ora, and an area known as Koura-te-uwhi. If you’re one of those who has made the trip to the beach races, you’ll be somewhat familiar with the area. Otherwise, you will be soon.

As you drive the main road north past Tolaga Bay,

look to your right just before the Kaiaua turnoff. This area is called Koura-te-uwhi, and runs all the way down the Kaiaua road to the beach.

One of the meanings of Koura-te-uwhi is “covered in crayfish”, refering to spots on this coastal seaboard which were renowned for this phenomenon. Another meaning is that the area was covered in native yams (uwhi) and, probably because of their colour, resembled crayfish.

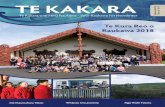

On the same road just past the turnoff from the main road is Puketawai Marae. The name of the whare tipuna (ancestral house) is Te Amowhiu, the mother of Te Rangi-pure-ora, the principal ancestor of the hapū. The whare kai (dining room) is called War Memorial Hall, commemorating the soldiers of the tribe who died in the two world wars.

The ancestor Te Rangi-pure-ora traces a direct

line of descent six generations from Hauiti. Hauiti lived during the period 1575AD, therefore Te Rangi-pure-ora lived around 1725. Many things happened between the time of Hauiti and Te Rangi-pure-ora and some of these events will be covered in the following stories.

That’s coming up, but what of Te Whānau-a-te-Rangi-pure-ora today? Who are they and where are they?

Well, the crayfish or yams of Koura-te-uwhi might not be as abundant today as before but the people certainly are, and you’re likely to find them everywhere — at Koura-te-uwhi, in Ūawa, in Tūranga, throughout Aotearoa and undoubtedly all over the world. So next time you meet someone from Te Āitanga-a-Hauiti, ask if they affiliate to Puketawai Marae — you’re likely to find a gem!

He MihiTēnā rā koutou ki tēnei te tekau mā

waru o ngā kōrero e mōhiotia nei ko, Ngā Maunga Kōrero o Te Tairāwhiti. Kua hoki whakamuri tā tātau haere ki roto o Ūawa anō, ki Koura-te-uwhi, ki Puketawai me ngā uri o Te Rangi-pure-ora. He uri tonu a Te Rangi-pure-ora i a Hauiti mai i tana tama, a Tamatea-pāia, heke iho ki te mokopuna i a Angiangi-te-rangi, ki tana ake mokopuna i a Te Amowhiu te kōkā o Te Rangi-pure-ora. Engari, waiho mā ngā kōrero e puaki, e whakamārama. Tēnā, e noho, whakatā mai, pānui mai, whakaarohia mai.

Welcome to the eighteenth issue in the series, Ngā Maunga Kōrero o Te Tairāwhiti. In this journey we return to Ūawa (Tolaga Bay), to the area known as Koura-te-uwhi, to Puketawai Marae and the descendants of their ancestor, Te Rangi-pure-ora. Te Rangi-pure-ora was a direct descendant of Hauiti through his son Tamatea-pāia, to his grandson Angiangi-te-rangi, then to his granddaughter Te Amowhiu, who was the mother of Te Rangi-pure-ora. But let the stories do the talking. Meanwhile, sit down, relax, read and let your thoughts wander.

Principal resources referenced for this collection include: Horouta (Halbert, 1999); Raurunui-a-Toi Lectures (Ngata, 1944); Tolaga Bay — A History of the Uawa District (Laurie, 1988); Te Amowhiu Wānanga Booklet (Victor Walker, July 4-6 2003). Tokamāpuhia (Wayne Ngata, 2003).

(A special thanks to Victor Walker, Cynthia Sidney, Wayne Ngata and Puketawai Marae)

Walton WalkerSchool of Humanities, Tairāwhiti Polytechnic.

Ō-manu-huruhuru and Te Whānau-a-Te-Rangi-pure-ora

BACK in the December 2007 issue of Maunga Kōrero - Tītīrangi and Ūawa, we followed the fortunes of Hauiti and his battle for supremacy over his elder brothers,

Taua and Māhaki-ewe-karoro. Hauiti eventually secured control over the land in and around Ūawa, including much of the lands occupied by his older brothers. All the while though, his brothers and their children continued to challenge him in a series of ongoing skirmishes. Therefore, to consolidate his hold, Hauiti strategically placed his children on the land.

Hauiti had two wives, the first, Kahukuraiti, was the daughter of Rongowhakaata and Moetai. Together they had nine children — daughters Hine-te-rā, Rongotīpare, Hine-kura and Pāhirauwaka, and sons Tamatea-pāia, Pīrau, Tāporo, Kahukuranui and Wawau. To his second wife, Rākau-manawa-hē, who was the daughter of Uepōhatu and Rangi-whaka-oma, he had another son, Kārihimāmā (Kārihimana in some text). These children would ultimately inherit and establish the mana of Hauiti as we recognise it today.

In the March 2008 issue of Maunga Kōrero – Marotiri and Tokomaru, we followed the adventures of Hauiti’s son, Kahukuranui, to whom the mantle of leadership was eventually passed and with whom the responsibility of consolidating the estate rested. Kahukuranui fought and killed his cousin Apanui-waipapa, the son of Taua, and took control of the lands of the Ūawa district.

Of no less importance in this consolidation process, though, was the part played by Kahukuranui’s half-brother, Kārihimāmā. Kaiaua, which was one of Taua’s residences, was left to his son Kōkoru. During the battles between the families, Kārihimāmā fought with and killed Kōkoru. Kārihimāmā took possession of Kaiaua, including the offshore fishing rocks called Toka-mā-puhia, which he subsequently named after himself.

Thereafter Kārihimāmā was joined by his brother Kahukuranui and together they affirmed their residence on Kaiaua, with the principal settlement being Mārau and their people becoming known respectively as Ngāti Rākau-manawa-hē (after Kārihimāmā’s

mother) and Ngāti Kahukuranui.From Kaiaua and Mārau, Kahukuranui took control of the

territories north to Tawhiti near Tokomaru. The mana of these lands would eventually pass on to his children — Tautini, Ake-tū-angiangi and Kapi-horomaunga.

Kapihoromaunga became the custodian of Kaiaua, Mārau and Toka-māpuhia, howevever his authority over these lands was lost to his brother Tautini, who was living at Toiroa pā at Tokomaru. In time Tautini’s interests would be inherited by his daughter Te Ao-tāwari-rangi and son Tū-te-rangi-ka-tipu, and then a grandson, Wakarara.

Of Hauiti’s other children, Pīrau and Tamatea-pāia were to inherit Koura-te-uwhi. Pīrau occupied the northern part of Koura-te-uwhi from Te Kōpuni to Tikopunga, while Tamatea-pāia occupied the southern side from Tikopunga to the Ūawa river mouth.

The inland boundary marker of the territory controlled by Pīrau and Tamatea-pāia was the Ūawa river. The principal pā were Motueka, an island just offshore, and Te Karaka.

Meanwhile, Hauiti’s daughters Hine-te-rā and Rongotīpare also featured in their father’s real estate plans. Hine-te-rā had control of the land from the Ūawa river mouth south, while Rongotīpare had the territories bordering the inland boundaries of her other siblings — Kahukuranui to the north, Hine-te-rā to the south and Pīrau and Tamatea-pāia to the east.

Rongotīpare, in fact, was land-locked and did not have any direct access to the sea, however, she would always have access privileges at the behest of her brothers. Whilst not obvious at the time, Rongotīpare’s desire to be closer to the sea would soon reveal itself.

Puketawai Marae with meeting-house Te Amowhiu (right) and dining-room, War Memorial Hall, (left).

Ō-manu-huruhuru, the ancestral mountain of Te Whānau-a-Te-Rangi-pure-ora.

Te Amowhiu, the mother of Te Rangi-pure-ora, at Puketawai Marae.

Hauiti Consolidates Control Over Ūawa

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI • FRIDAY, DECEMBER 5, 2008 • 27

KŌRERO O TE TAIRĀWHITI

HAUITI’S children all played an important part in consolidating his control over Ūawa and the lands that

once belonged to his older brothers, Taua and Māhaki. But ongoing skirmishes with Taua and Māhaki’s children and their supporters also had drastic consequences for Hauiti which could have threatened this hold on these lands.

On a fateful campaign to Tūranga (Gisborne), Hauiti’s sons Tamatea-pāia, Pīrau and Tāporo were all killed, whilst Hauiti was mortally wounded. When news of the deaths reached Ūawa, Hauiti’s daughter Rongo-tīpare undoubtedly grieved her father and brothers’ passing, but also saw an opportunity to assert her seniority and secure the lands belonging to Tamatea-pāia and Pīrau.

Rongo-tīpare, who lived inland from the coast, moved with her people on to Koura-te-uwhi with the intention of occupying these lands as well. She did so and lived together with the descendants of

Tamatea-pāia and Pīrau at Te Karaka pā.Meanwhile, Angiangi-te-rangi, a grandson

of Tamatea-pāia, and therefore a grand-nephew of Rongo-tīpare, had risen to prominence to become the leader of his people. He resented the intrusion by his grand-aunt but tolerated her presence. Things changed for the worse, though, when a gale arose at sea and smashed newly-made crayfish pots — Rongo-tīpare saw this as an ill omen and became fearful. She left Te Karaka pā and shifted inland, residing at Pā-oneone (near the present rubbish dump at Tolaga Bay), but was still determined to occupy Koura-te-uwhi.

Some time later, Angiangi-te-rangi’s dog Puhunui was captured and killed by the occupants of Pā-oneone. This was a prelude to war and Angiangi-te-rangi engaged the services of his cousin Te Whaka-piu-a-rangi, at Whanga-parāoa (Cape Runaway), to raise a war party. Whaka-piu-a-rangi was a descendant of Hine-

te-rā, Hauiti’s eldest daughter. Thus, Angiangi-te-rangi marched on Pā-oneone to attack his aunt Rongo-tīpare for the overtures she was making towards Koura-te-uwhi and for the death of his dog, Puhunui.

The battle resulted in Rongo-tīpare’s death together with other principal chiefs Rākai-whare-wai (Rongo-tīpare’s son) and Kahu-tāpere. The lands of Tamatea-pāia and Pīrau were once again restored to their descendants and their mokopuna, Angiangi-te-rangi. However, the survivors of Pā-oneone enlisted the aid of Hika-wehea, who

was a mokopuna of Kuranui of Ngāti Kuranui fame, to avenge the death of Rongo-tīpare and together defeated Angiangi-te-rangi at the battle of Tai-porotū. Angiangi-te-rangi survived the battle but retreated to Te Kōpuni (at Kaiaua). He still, however, continued to reside on Koura-te-uwhi. Some of Rongo-tīpare’s descendants also remained on Koura-te-uwhi. However, it was Angiangi-te-rangi’s mana that would endure and this responsibility would ultimately pass on to his granddaughter Te Amowhiu and her son Te Rangi-pure-ora.

Angiangi-te-rangi and Rongo-tīpare —What You Doing Nan?

OUT from the beach at Kaiaua and the ancient pā site of Mārau lies a

cluster of rocks renowned for its kaimoana (seafood) called Toka-māpuhia. On a clear day you might be able to see them, or the white caps of breaking waves will indicate their location. The story of the rocks is shrouded in legend and goes back to a time when dates were a bit of a blur.

The story begins at Manga-tokerau, located just a little way up the valley f rom the present Mangatuna School.

There, next to the river called Toka-māpuhia, lived a woman and her chi ldren who were desperately hungry. Her children were continually crying, so she was forced to go in search of food.

At Mā-kawakawa, where the river divides, a tohunga (priest) greeted her but also cautioned her about a pregnant chieftainess roaming the area who could bring misfortune to her quest if she crossed her trail. She continued her search and at Para-te-nohonoa, where the Hikuwai river divides, she was cautioned by another tohunga who advised her to head north lest she crossed the path of the pregnant cheftainess who was in the south.

The cries of her hungry children grew stronger so, through the power of karakia (prayer and incantation), she changed herself into a dog so as to hasten her journey in search of food.

Ignoring the advice of the tohunga about the pregnant woman in the south, she headed in that direction anyway for there was no food to be found in the north.

Sure as the tohunga had warned, the woman crossed the trail of the pregnant chieftainess at a

place which became known as Whatikawa — to break (whati) the rule (kawa).

The impact of this indiscretion wasn’t immediately seen and the woman continued on her way.

By nightfall her search had taken her to the sea, surely she would find food there! But that too was in vain.

Despite searching all night, she couldn’t find even a scrap of food.

All the while the woman was well aware of the incantation she had performed upon herself that turned her into a dog.

But driven by the hunger of her children, she lost all track of time. When the morning sun rose in the east she was still out at sea. And there she remains to this day, caught by the rising sun and turned into a rock — a rock, it is said, that is shaped like a dog, the rock that bears the name Toka-māpuhia.

Meanwhile, her children who were left ashore searched in vain for their mother and, like their mother, they too were transformed into rock, one at Rototahe (Puatai, Whāngārā) and the other at Ūawa.

Another interesting phenomenon about Toka-māpuhia is that a f reshwater spring flows f rom it and the origin of the spring has been traced back to Mā-kawakawa at Manga-tokerau, where it runs underground out to sea.

Also, Toka-māpuhia was the name of the pā belonging to Te Aotaki and Hinemaurea at Wharekahika, who had their origins in the area described in this story.

In life, Tokamāpuhia could not find food to feed her children. However, in her transformation, she has become a bountiful food provider for endless generations of her descendants.

The rocks of Toka-māpuhia lie amongst the white caps off the tip of Mārau at Kaiaua.

Toka-māpuhia —No Ordinary Rock!

Toku ate kei te ao e rere nei ki runga o Ō-kū-kekaMy yearning heart lingers on the cloud over Ō-ku-keka

Ōrite ana ki runga o Ō-manu-huruhuruAs it does on the clouds over Ō-manu-huruhuru

He aha te rangi ka ūhia te huruhuru te manu ka rere?What day will bring the feathers for the bird to fly?

IN the aftermath of Angiangi-te-rangi’s battle with his grand-aunt, Rongo-tīpare, his sister Whiwhinga married Te Whakapiu-a-rangi, the cousin who he enlisted to

help him fight against Rongo-tīpare. They had a child, Te Whakahī-o-te-rangi, who in turn had a daughter, Te Waho-te-ngatata. Te Waho-te-ngatata married Te Heke-o-te-rangi and together they lived at Whāngārā.

When Te Heke-o-te-rangi lay dying, a messenger was sent to fetch Pārua-o-Teina, another great chief of the area, who was living at Ūawa. Pārua-o-Teina was a direct descendant of Hauiti, through Kahukuranui, to Tautini, to Tū-te-rangi-ka-tipu, and to his father Te Rangi-tau-ki-waho. Te Rangi-tau-ki-waho married Māriu, the daughter of Tūwhaka-iri-ora and his second wife Te Ihiko-o-te-rangi. Another child born of this union, and sister to Pārua-o-Teina, was Hine-tāpora, a principal ancestress of the Ruatōria area.

When Pārua-o-Teina arrived to the bedside of the dying Te Heke-o-te-rangi, he instructed him that after his death he was to look after his wife, Te Waho-te-ngatata. Parua-o-Teina agreed and after Te Heke-o-te-rangi’s death returned to Ūawa with Te Waho-te-ngatata. They had a child named Te Ao-pua-angiangi who resided with her mother at Wairere near Te Ūpoko-o-te-Ika (Cooks Cove). Pārua-o-Teina also married Te Amowhiu and had three children, including Te Rangi-pure-ora. When Pārua-o-Teina died, Te Rangi-pure-ora went to fetch his half-sister Te Ao-pua-angiangi from Wairere and settled her at Te Karaka pā on Koura-te-uwhi. The people living in the area were all descendants of Pīrau and Tamatea-pāia.

A later incident involving the death of Te Rangi-hema, a tohunga (high priest) of Te Whānau-a-Pīrau, at the hands of an invading war party, saw Te Rangi-pure-ora place a rāhui (prohibition) on the land where he was killed. This was on account of the area being rendered tapu (sacred) by the spilling of Te Rangi-hema’s blood on the land, namely Paerau pā.

Te Rangi-pure-ora instructed the people of Te Whānau-a-Pīrau to also observe the rāhui and seek another place to live while he himself took refuge in Whāngārā.

Te Whānau-a-Pīrau ignored his instructions and instead bade him farewell. In time this would have serious ramifications.

Te Rangi-pure-ora stayed in Whāngārā for two years but yearned to return home. Upon seeing a cloud going seaward, he uttered the words, Toku ate kei te ao e rere nei ki runga o Ō-kū-keka, ōrite ana ki runga o Ō-manu-huruhuru. He aha te rangi ka ūhia te huruhuru te manu ka rere? When Konohi, the principal chief of the Whāngārā area, heard Te Rangi-pure-ora’s words he said he would return him. Konohi sent a messenger to Te Ika-whai-ngata, a chief of Rongo-whakaata in Tūranga, to raise a tauā (war party). When the tauā arrived, Te Rangi-pure-ora asked that they not travel by the beach where his sister Te Ao-pua-angiangi lived, but by the inland track instead.

When the war party arrived at Ō-manu-huruhuru they completely sacked the pā, Te Waipuna, the house Wai-ora-tāne and the chiefs Tū-te-rangi-wetea and Te Kai-whakaaro, together with Te Whānau-a-Pīrau. The battle also spread to Te Karaka pā.

Following the battle, Konohi’s patu parāoa (whale-bone club) was washed in a stream that became known as Te Wai-horoi-a-Titinapua — The washing place of Titinapua (the name of Konohi’s club).

Te Rangi-pure-ora was restored as the principal chief of the area and took possession of all the lands north from the mouth of the Ūawa river to Ō-manu-huruhuru. The families of Te Rangi-pure-ora and his sister Te Ao-pū-angiangi became collectively known as Te Whānau-a-Te-Rangi-pure-ora, with the principal pā being Motueka. The descendants of Te Rangi-pure-ora remain in occupation of these lands to the current day.

Motueka Island, one of the principal pā of Tamatea-pāia, Pīrau and their descendants.

Te Karaka pā with Motueka island. Te Karaka pā from sea-level.

Te Rangi-pure-ora — I’ll Be Back

Kapu-a-rangi (foreground), Wai-o-tapu (stream) and Te Karaka pā (background left).