Sacred Duets - booklets.idagio.com · San Casimiro, re di Polonia | Firenze 1705 | Libretto: Anon....

Transcript of Sacred Duets - booklets.idagio.com · San Casimiro, re di Polonia | Firenze 1705 | Libretto: Anon....

2

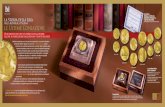

ALESSANDROSCARLATTI(1660–1725) SanCasimiro,rediPolonia|Firenze 1705 | Libretto: Anon.1 Duetto: Al serto le rose 2.58

BERNARDOPASQUINI(1637–1710) Sant’Agnese|Modena 1685 | Libretto: Benedetto Pamphili2 Aria: Vaga rosa 3.34

GIOVANNIPAOLOCOLONNA(1637–1695) Salomoneamante | Bologna 1679 Libretto: Giacomo Antonio Bergamori3 Duetto: Partite dolori 2.534 Aria: Su l’arco d’amore 4.13

DOMENICOGABRIELLI(1651–1690) SanSigismondo,rediBorgogna Modena 1689 | Libretto: Domenico Bernardoni5 Aria: Aure voi de’ miei sospiri 5.49

GIOVANNIBONONCINI (1670–1747) LaconversionediMaddalena | Wien 1701 | Libretto: Anon.6 Aria: Cor imbelle a due nemici 3.29

GIUSEPPETORELLI(1658–1709) Concertigrossiop.VIII| Bologna 1709 ConcertoVIIIcon un violino che concerta solo7 I. Vivace 3.348 II. Adagio 0.299 III. Allegro 2.09

Sacred Duets ANTONIOLOTTI(1667–1740) L’umiltàcoronatainEsther | Wien 1714 | Libretto: Pietro Pariati10 Duetto: Sempre fido, sempre grato 3.44

ANTONIOCALDARA (1670–1736) Lafrodedellacastità| Roma 1711 | Libretto: Anon.11 Aria: Si pensi alla vendetta 2.59

SantaFrancescaromana | Roma 1710 | Libretto: Anon.12 Duetto: È ristoro a un cor che pena 4.35

NICOLAANTONIOPORPORA(1686–1768) IlVerboincarne| Napoli 1747/48 Libretto: Giovanni Giuseppe Giron13 Duetto: Lascia ch’io veda almeno 6.38

Gedeone| Wien 1737 | Libretto: Francesca Manzoni Giusti14 Aria: Quasi locuste che intorno 3.59

IlmartiriodiSanGiovanniNepomuceno Venezia c. 1730 | Libretto: Carlo Emanuele d’Este di San Martino15 Duetto: Della fragile mia vita 9.21

Nuria Rial soprano (1–4, 6, 10, 12, 13, 15)

Valer Sabadus countertenor (1, 3, 5, 10–15)

Julia Schröder solo violin (5–9)

Simon Linné solo theorbo (5) · Hristo Kouzmanov solo cello (5)

Kammerorchester Basel

2

3

violin/Violine I: Julia Schröder · Mirjam Steymans-Brenner · Regula Schär · Tamás Vásárhelyiviolin/Violine II: Yukiko Tezuka · Ewa Miribung · Carolina Mateosviola: Bodo Friedrich · Joanna Bilgercello/Violoncello: Hristo Kouzmanov · Georg Dettweilerdouble-bass/ Kontrabass: Daniel Szomorharpsichord/Cembalo: Francesco Pedrini · organ/Orgel: Francesco Pedrinitheorbo/Theorbe: Simon Linné

www.maierartists.de/nuria-rial.htmlwww.valer-sabadus.de www.kammerochesterbasel.ch

P & g 2017 Sony Music Entertainment Germany GmbH

Special thanks to Freundeskreis Kammerorchester Basel

for the generous support of the album production.

Recording: Riehen, Landgasthof Riehen, 18–21/03/2016

Recording Producer, balance engineer, editing & mastering: Jakob Händel

Concept, musicological research, edition of scores: Giovanni Andrea Sechi © 2016

Critical edition of “Su l’arco d’Amore”: Francesco Lora © 2016

Executive Producer: Stephanie Wieck · Total time: 62.31

Artwork: Christine Schweitzer · Cover photos: Henning Ross (Sabadus)

Merçè Rial (Rial) · g Irina_QQQ/shutterstock (Background)

Blättert man die Partitur einer beliebigen Opera seria des 17. oder 18. Jahrhun-derts durch, stößt man unweigerlich auf ein oder mehrere Duette; in den Orato-rien dieser Zeitspanne sind Duette dagegen nur selten zu finden. Die Sitte, jedes Oratorium mit einem Madrigal zu be enden, in das alle im Werk vertretenen Figu-ren einstimmen, mag Librettisten davon abgehalten haben, weitere Nummern für zwei Solostimmen zu schreiben. Die wenigen Duette in italienischen Oratorien der Jahre 1670 bis 1740 – in etwa die Periode, die dieses Album abdeckt – dienen meist als Übergangsszenen. Sie schildern vorwiegend Begegnungen zwischen Menschen und personifizierten moralischen Werten, Dialoge zwischen Tyran-nen und christlichen Märtyrern, Versöhnungen zwischen Eltern und Kindern, Gebete von Heiligen im Angesicht ihres Martyriums, die von göttlichen Instan-zen erhört werden, usw.

Dennoch: Wie die vorliegende Musikauswahl beweist, setzten sich einige Komponisten intensiv mit dieser speziellen Spielart des Duetts auseinander und erhoben sie in einen Rang, der dem der großen Arien für die Hauptfiguren in nichts nachsteht.

Die Erweiterung des musikalischen Materials ist Ende des 17., Anfang des 18. Jahrhunderts auch in der Arie zu beobachten. Der Siegeszug der dreiteiligen Arie (ABA) verdrängt nach und nach die Strophenarie, sowohl im Oratorium als auch in der Opera seria. Diese Entwicklung schlägt sich im vorliegenden Al-bum nieder, das auch einige Verschmelzungen der alten Form (wie bei Pasquini und Colonna) mit frühen Beispielen der modernen Da-capo-Arie (Gabrielli) ent-hält. Unsere Auswahl präsentiert Stücke der bedeutendsten italienischen Schu-len: Bologna, Rom und Neapel. Die chronologische Reihenfolge veranschau-licht einerseits die stilistische Reifung der einzelnen Komponisten im Kontext ihrer jeweiligen Herkunft, andererseits die grundlegenden geschmacklichen

Entwicklungen, die zur Überwindung der regionalen Unterschiede – und schließlich zum internationalen Erfolg des galanten Stils – führten.

Weder Bernardo Pasquini (1637–1710) noch Alessandro Scarlatti (1660–1725) stammten aus Rom; trotzdem gelten beide mit Fug und Recht als Vertreter der Römischen Schule. Sie studierten nicht nur in der Papst-Metropole, sondern feierten hier auch ihre größten Erfolge. Diese verdankten sie einerseits langjäh-rigen engen Beziehungen zur Elite der römischen Kunst mäzene wie etwa den Kardinälen Ottoboni und Pamphili, andererseits der Zugehörigkeit zu exklusi-ven Zirkeln wie der Accademia dell’Arcadia. Die Vorliebe der römischen Komponis-ten für das Oratorium prägte sich in der zweiten Hälfte des 17. Jahrhunderts immer stärker aus. Der Grund hierfür war rein politischer Natur: die Verteufelung des Theaters durch den Vatikan. Die Zeit der stärksten Repression war das Pontifi-kat von Innozenz XII., der 1697 den Abriss des Teatro Tordinona verfügte. In-folge der ständigen Verbote etablierte sich das Oratorium als Opera- seria-Al-ternative. Mit seinem Vermächtnis von mindestens 38 Oratorien und geistlichen Kan taten, teils in italienischer, teils in lateinischer Sprache, zählt Scarlatti zu den produktivsten Komponisten seiner Generation. Aus seinem Oratorium San Ca-simiro, re di Polonia (Florenz 1705) stammt das Duett „Al serto le rose“, ein schneller Tanz im Duktus einer Gigue. Die Arie „Vaga rosa“ aus Pasquinis Santa Agnese (Modena 1685) erwähnt ebenfalls die Rose, jedoch eher in metaphori-schem Sinne. Vom Librettisten Benedetto Pamphili inspiriert, schuf der Kom-ponist eine thematisch ausgesprochen vielseitige Arie, die den moralischen Subtext der Verse mit seinem Verweis auf die Vergänglichkeit des Lebens tref-fend zum Ausdruck bringt.

Die inspiriertesten Oratorienkomponisten der Epoche stammten zum Groß-teil aus der Schule von Bologna, darunter Giovanni Paolo Colonna (1637–1695),

Innovation und Tradition im italienischen Oratorium 1670–1740

4

Kapellmeister an der Basilica di San Petronio. Der Meister des strengen Kon-trapunkts und der altüberlieferten Kompositionstheorie wurde in ganz Bolog-na als Autorität verehrt. Jenseits der Stadtmauern allerdings machte er sich mit seinem stolzen, herrischen Charakter diverse Feinde (darunter selbst Arcange-lo Corelli, aufgrund einer Kontroverse bezüglich der Quintparallelen in seinen Sonaten op. 2). Das vorliegende Album präsentiert zwei Titel aus Colonnas Sa-lomone amante (Bologna 1678). Francesco Loras Studien zufolge handelt es sich hierbei aufgrund der gewaltigen Sängerbesetzung (ganze acht Personen) und der langen Dauer (fast drei Stunden) um das imposanteste Oratorium dieser Periode. Ein solches Monumentalwerk, das sich an ein gebildetes und aufgeschlossenes Pu-blikum richtete, konnte der Aufmerksamkeit des Herzogs von Modena Frances-co II. d’Este – seines Zeichens der großzügigste Förderer der Gattung Oratori-um in den 1670er bis 1690er Jahren – nicht entgehen. Die Besonderheit und Opulenz des Werks offenbaren sich auch in den beiden Stücken dieses Pro-gramms. In der Arie „Su l’arco d’Amore“ zieht Colonna, um die absolute Gewiss-heit und die sinnlichen Ambitionen der Ersten Phönizierin zum Ausdruck zu brin-gen – die mit einer Zweiten Dame um König Salomos Liebe konkurriert –, sämtliche ihm zur Verfügung stehende instrumentale Register: Zwei Solovioli-

nen führen einen gleichberechtigten Dialog mit der Gesangsstimme – ein imita-tives Spiel, reich an Dissonanzen, bei intensiver Durchführung des themati-schen Materials. Dabei sind die Strophen länger als üblich, und das thematische Material gliedert sich klar in drei Teile. (Die Idee der dreiteiligen Arie schim-mert hier bereits durch.)

Neben den bereits erwähnten formalen Neuerungen kam es im 17. Jahrhundert auch besetzungs technisch zu bedeutenden Innovationen: 1665 wurde zum ersten Mal in einem Musikwerk aus drücklich das Cello genannt, in einer Sammlung mit Instrumentalmusik des bolognesischen Komponisten Giulio Cesare Arresti (Dodici sonate a due e a tre, con la parte del violoncello beneplacito op. 4). In Bologna nahm dann auch die Emanzipation des Cellos vom Basso continuo ihren Lauf: In den folgenden Jahren setzte sich unter den dortigen Komponisten immer mehr das so genannte violoncello spezzato durch, eine unabhängige Cellostimme, losge-löst vom Basso continuo. Das wachsende Interesse an diesem Instrument schlug sich auch in einer Vielzahl von in Bologna ausgebildeten Cellovirtuosen nieder, dar-unter die Brüder Giovanni und Antonio Maria Bononcini, Giuseppe Maria Jacchini und Domenico Gabrielli. Letzterer adelte das Cello schließ lich in seinen Werken zum Soloinstrument. Gabrielli war jedoch nicht nur für seine Ricercarii für Cel-

5

Alessandro ScarlattiAntonio Caldara Nicola Porpora Giovanni Battista Bononcini

6

lo solo bekannt (eine der anspruchsvollsten Cellokompositionen vor Bachs be-rühmten Suiten), sondern auch als Komponist von Opern und Oratorien. Die Arie „Aure voi de’ miei sospiri“ aus Sigismondo re di Borgogna (Modena 1687) wartet mit einem großen Begleitensemble und einem für damalige Verhältnisse recht ungewöhnlichen Solisten-Trio auf: Cello, Geige und Theorbe. Die drei So-loinstrumente stehen in engem Dialog mit der Gesangsstimme und dem Or-chester, wobei sie unter einfallsreicher Verwendung verschiedener Klangfar-ben mit dem im Text erwähnten Motiv des Echos spielen („lasst meine Seufzer widerhallen“).

Der Meister der weltlichen Vokalkomposition Giovanni Bononcini (1670–1747) war ebenfalls ein erfolgreicher Oratorienkomponist: Seine Werke waren in ganz Europa bekannt. Seinen Ruhm verdankte Bononcini nicht nur seinem kom-positorischen Talent, sondern auch seinem Wirken in eben den Städten, die an der Förderung und Verbreitung der Gattung Oratorium maßgeblich beteiligt waren: Bologna, Modena (am Hof von Francesco II.), Rom und Wien (zunächst im Dienst von Kaiser Leopold I., später von Joseph I. und schließlich von Karl VI.). Während seines ersten Aufenthalts in der habsburgischen Metropole ent-stand die Arie „Cor imbelle a due nemici“ aus dem Oratorium La conversione di Maddalena (Wien 1701). Die traditionelle Vorliebe des Wiener Hofs für Arien mit konzertanter Begleitung zeigt sich hier deutlich: Der virtuose Gesang der Magda-lena – eine recht blumige Illustration der an ihr nagenden Zweifel – findet in der Solovioline einen würdigen Mitstreiter. Diese Arie besticht vor allem durch ihre Sanglichkeit – ein typisches Merkmal der Schule von Bologna – und ihre meisterhaft komponierten Ritornelle, die an die Lehrjahre des Komponis-ten im Rom erinnern.

Antonio Caldara (1670–1736) wurde in Venedig geboren, aber sein Aufent-halt in Rom 1711–1716 sollte ihn nachhaltig prägen. Davon zeugt nicht zuletzt der umfangreiche Katalog seines oratorischen Schaffens in Ursula Kirkendales Monographie von 1966, der ganze 42 Titel verzeichnet. La frode della castità (Rom 1711) wurde möglicherweise ursprünglich für Venedig geschrieben, aber nach-weislich auch am Hof des Fürsten Francesco Maria Ruspoli aufgeführt. Aus die-sem Oratorium stammt die Arie „Si pensi alla vendetta“, die als Parodie der Arie „Io parto a vendicarmi“ aus der Oper Arminio (Genua 1705) von besonderem musikwissenschaftlichen Interesse ist. Die hier zitierte Musik der rachsüchti-gen Climene bedurfte nur geringer Modifikationen, um sie dem heidnischen Tyrannen Meraspe zu übertragen, der angesichts seiner Zurückweisung durch die junge Christin Eufrasia zutiefst gekränkt ist. Die Zweitverwertung einer Opernmusik im Oratorium war zur damaligen Zeit nichts Ungewöhnliches. (Ein weiteres Beispiel ist die oben genannte Arie von Gabrielli, die in schlichterer Form auch in seiner Oper Il Maurizio zu finden ist.) Anhaltender Beliebtheit er-freute sich Caldara vor allem in Wien: Hier sind dank des unermüdlichen Einsat-zes von Sammlern wie Raphael Georg Kiesewetter (1773–1850) mehrere Auf-führungen Anfang des 19. Jahrhunderts belegt. Kiesewetters Studien inspirierten weitere Wiener Gelehrte, sich mit der Musik des vorangegangenen Jahrhunderts zu befassen. So kam es, dass Simon Molitor im Rahmen der For-schungen für seine Musikgeschichte in Österreich (ca. 1830) Caldara und seine Oratorien studierte, darunter auch S. Francesca Romana (Rom 1711). In seinem Traktat wählte Molitor das Duett „È ristoro a un cor che pena“ aus eben diesem Oratorium als exemplarisches Beispiel für die Gattung.

Die Komponisten der Neapolitanischen Schule pflegten das Oratorium nicht we-

7

niger intensiv; besonders produktiv war Nicola Antonio Porpora (1686–1768). Il martirio di San Giovanni Nepo muceno (ca. 1730) war ursprünglich zur Aufführung in Venedig bestimmt, wie das einzige erhaltene Exemplar der Partitur belegt (heute in der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek Wien, Libretto verschol-len). Der Ort und ungefähre Zeitpunkt der Entstehung erscheinen umso plau-sibler, als die Musik stilistisch den Werken, die Porpora nachweislich während seines Aufenthalts in Venedig 1726–1731 schrieb, vollkommen gleicht. Ein wei-teres belastbares Indiz sind die Kanonisation Johannes Nepomuks und seine besondere Beziehung zur Lagunenstadt. Johannes Nepomuk, den man nicht nur in Prag (aufgrund seiner böhmischen Wurzeln), sondern auch in Venedig besonders verehrt, wurde 1729 heilig gesprochen. Der Patron des Beichtge-heimnisses und Brückenheilige war als Schutzpatron der Gondolieri eine fun-damentale Größe im venezianischen Leben. Die Partitur des Oratoriums iden-tifiziert den Autor der Textvorlage als »Marchese d’Este Santa Cristiana«, bei dem es sich nach modernem Forschungsstand um Carlo Emanuele d’Este di San Martino (vor 1703–1766) aus einer Seitenlinie des Herrscherhauses von Mode-na handelte. Das Duett »Della fragile mia vita« besticht durch die gelungene Kombination von akademischem Kontrapunkt und sanglichen Melodien sowie den findigen Einsatz von Koloraturen und Ornamenten. Das kunstvolle Duett ist eine Hommage an die hohe Tradition des Kammerduetts, jedoch mit kräfti-gerer Instrumentalbegleitung. (Bei Antonio Lotti, Carlo Luigi Pietragrua und Agostino Steffani werden die Gesangsstimmen nur vom Basso continuo beglei-tet.)

Das zweite Duett von Porpora in diesem Programm, „Lascia ch’io veda alme-no“ aus Verbo in carne (Neapel 1747), stammt aus einem der seltenen Weihnachts-

oratorien (eine im damaligen Italien absolut unkonventionelle Form geistlicher Vokalmusik zum Weihnachtsfest). Auch dieses Werk ist aufgrund seiner Quellen-lage ein interessantes Forschungsobjekt. Meiner Meinung nach wurde das Orato-rium nicht, wie in der bisherigen Fachliteratur angenommen, für Rom oder Dresden, sondern für Neapel komponiert. Der Fund eines gedruckten Librettos (Bibliothek der Società Napoletana di Storia Patria, Neapel), das Giovanni Giu-seppe Gironda (vor 1708–1753) als Autor der Textvorlage verzeichnet, unter-mauert diese These. Neapels Einfluss auf das Werk zeigt sich auch in der anmu-tigen Darstellung der Heiligen Familie, die im Stil einer barocken Weihnachtskrippe gezeichnet ist. Nach einer lebhaften Diskussion über das Schick sal der Menschheit lässt der Anblick des Jesuskinds in der Krippe die al-legorischen Figuren der Gerechtigkeit und des Friedens in diesem galanten Menuett neue Hoffnung schöpfen.

Die vorliegende Musikauswahl beweist: Obwohl oft ignoriert und nur selten gespielt, ist das italienische Oratorienrepertoire des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts reich an Titeln, die es wert sind, ins Musikleben zurückzufinden. Dieser Exkurs am Bei-spiel heute sowohl häufig gespielter als auch weniger geläufiger Komponisten ist eine Einladung, dieses Genre bewusst wiederzuentdecken.

© 2016 Giovanni Andrea SechiÜbersetzung: Geertje Lenkeit

Leaf through the score of a seventeenth- or eighteenth-century opera seria and you will probably come across a duet or two. Scan the pages of an oratorio from the same period and you are far less likely to do so. It was customary to end an ora-torio with a chorus (or “madrigale”) for all the soloists, and this may have dis-couraged librettists from including other numbers for two voices. The few ex-amples of duets to be found in Italian oratorios written between 1670 and 1740, which is roughly the period covered by the works on this album, are nearly all just brief, transitional pieces, most of which deal with such situations as a clash between a mortal and a personified virtue, a dialogue between a tyrant and a Christian martyr, leave-takings between a parent and child, a prayer uttered by saints just before martyrdom, and so on.

That said, as we shall hear in this selection, some composers began to treat the duet form with increasing seriousness, endowing it with as much – if not more – musical dignity as they did any full-scale solo aria. Between the late 1600s and early 1700s, the aria itself was expanded in similar fashion, as the ternary (ABA) form established itself and the strophic version gradually disappeared, in both oratorio and opera seria. That development is reflected in the music ap pearing on this album, which also features various amalgams of the original model (Pas-quini and Colonna) and the earliest examples of the modern da capo aria (Ga-brielli). The programme includes pieces by the leading representatives of the different Italian schools (Bologna, Rome and Naples), enabling us to observe both how the style of individual composers matured over the years, and how changes in musical taste resulted in the sweeping away of regional differences (and in the establishment of the galant style throughout the musical world).

Though neither man was born in the city, both Bernardo Pasquini (1637–1710) and Alessandro Scarlatti (1660–1725) could claim to be fully paid-up members

of the Rome school. They trained there and enjoyed their greatest professional achievements there, thanks in part to their connections with the city’s leading patrons – figures such as Cardinals Ottoboni and Pam phili – and in part to their membership of such exclusive groupings as the Arcadian Academy. In the latter years of the seventeenth century it was politically expedient to compose orato-rios as the papacy grew more distrustful of opera and its effect on public mor-als. The period of greatest hostility and repression came with the pontificate of Innocent XII, who in 1697 ordered the demolition of the Teatro Tordinona. Composers were therefore left with little alternative but to write oratorios in-stead and, with at least thirty-eight oratorios and sacred cantatas to his name, setting texts in both Italian and Latin, Scarletti was one of the most prolific of his generation. The duet “Al serto le rose”, a lively dance in gigue tempo, is taken from his San Casimiro, re di Polonia (Florence, 1705). A more extended al-legorical treatment of the same floral theme can be found in the aria “Vaga rosa” from Pasquini’s Santa Agnese (Modena, 1685). Inspired by the erudite style of Benedetto Pamphili, the composer created an aria whose wealth of the-matic ideas enhance his poetry’s moral subtext, with its allusions to the tran-sient nature of human existence.

The Bologna school produced several of the most inspired composers of orato-rio, including Giovanni Paolo Colonna (1637–1695), maestro di cappella of the Basilica of San Petronio. A master of counterpoint and compositional theory at its most orthodox, he gained lasting fame in his home city. Further afield, however, his arrogance and authoritarian manner earned him more than one enemy (in-cluding no less a figure than Arcangelo Corelli, when Colonna questioned his use of parallel fifths in the Sonatas, op. 2 – a dispute that became known as the “affair of the fifths”). Colonna is represented here by two numbers from his

Innovation and Tradition in the Italian Oratorio 1670–1740

8

oratorio Salomone amante (Bologna, 1678): as demonstrated by musicologist Francesco Lora, this was the most imposing such work of its time, in that it called for a team of eight vocal soloists and took almost three hours to perform. A work on such a monumental scale, conceived for a cultured audience eager for new musical experiences, must have impressed Francesco II d’Este, Duke of Mode-na, the greatest patron of the genre between the 1670s and 1690s, and its opu-lent and idiosyncratic nature can be heard in the two extracts included here. In the aria “Su l’arco d’Amore”, Colonna uses his instrumental resources to bril-liant effect to convey the self-assurance and sensual allure of the First Sidonian Woman, who is competing for the love of King Solomon with one of her compa-triots: two solo violins establish a dialogue on almost equal terms with the voice, in a piece of imitative writing rich in dissonances and elaborations of the thematic material. The strophes here are more extended than usual, with an internal subdivision of the thematic material into three distinct parts (an early glimpse of the concept of the ternary aria).

As well as witnessing formal innovation, the seventeenth century also saw changes in the way instruments were used in vocal accompaniment. The earli-est recorded use of the term violoncello, for example, dates from 1665, when it

appeared in an instrumental anthology by the Bolognese composer Giulio Ce-sare Arresti (12 Sonatas a 2 & a 3, op.4). It was also in Bologna that the cello was first set free from the confines of the continuo line: the term “violoncello spez-zato” began to appear in scores, meaning an independent cello line, distinct from the continuo part. The growing interest in the instrument can also be seen in the succession of great virtuoso players emerging in Bologna, notably broth-ers Giovanni and Antonio Maria Bononcini, Giuseppe Maria Jacchini and Do-menico Gabrielli. It was the last-named who raised the cello to the status of soloist in his own works. Known for his Ricercares for solo cello (some of the most difficult pieces written for the instrument before the Bach Suites), Gabrielli was also a well-known opera and oratorio composer. His aria “Aure voi de’ miei sospiri”, from Sigis mondo re di Borgogna (Modena, 1687), is accompanied by a sizeable en-semble, including a somewhat unusual trio of soloists for the time: cello, violin and theorbo. Together they weave a closely knit dialogue with the voice and the other instruments, as Gabrielli plays with the blending of different timbres and with the idea of an echo, as mentioned in the text (“fate l’eco ai miei sospiri”).

An immensely talented composer of secular vocal music, Giovanni Bononci-ni (1670–1747) was also an oratorio specialist, whose works in the genre were

Bernardo PasquiniAntonio Lotti Giovanni Paolo Colonna Giuseppe Torelli

9

known across Europe. Such fame was due not only to the quality of their writ-ing, but also to the high-profile locations in which they were performed, guar-anteeing their dissemination: Bologna, Modena (at the court of Francesco II), Rome and Vienna (where Bononcini was in the service of Leopold I, then Jo-seph I and, finally, Charles VI). The aria “Cor imbelle a due nemici” from La con-versione di Maddalena (Vienna, 1701) dates from his first period of service in the Habsburg capital. It illustrates the historical predilection of the Viennese court for arias with concertato accompa niment: Bononcini matches the virtuoso vocal line he creates for Mary Magdalene – a highly ornate portrayal of the doubts assailing her – with an equally demanding part for solo violin. The aria is a fine example of the cantabile style typical of the Bologna school and of the compos-er’s beautifully written ritornellos, a legacy of his apprenticeship in Rome.

Born in Venice, but profoundly influenced by a period spent in Rome be-tween 1711 and 1716, Antonio Caldara (1670–1736) wrote at least 42 oratorios, as catalogued in 1966 by Ursula Kirkendale. They include La frode della castità (Rome, 1711), which may have been written for Venice but is known to have been performed at the court of Prince Francesco Maria Ruspoli in Rome. The aria “Si pensi alla vendetta” is of considerable musicological interest in that it is a parody of “Io parto a vendicarmi” from the opera Arminio (Genoa, 1705). The agitated music written for the vengeful Climene did not need much alteration to fit the character of the pagan tyrant Meraspe, whose pride is wounded when he is rejected by the Christian virgin Eufrasia. It was not uncommon during this period for music to be transferred from an opera to an oratorio (cf the Gabrielli aria in-cluded here, an earlier incarnation of which had already appeared in his opera Il Maurizio). Caldara’s fame was particularly long-lasting in Vienna – we know that

his works were still being performed there in the early years of the nineteenth century, thanks to the efforts of collectors such as Raphael Georg Kiesewetter (1773–1850). His books and articles encouraged an interest in the music of the previous century among other Viennese scholars, including Simon Molitor. He began to study Caldara and his oratorios as part of the research that led to his treatise on the history of Austrian music (Musikgeschichte in Österreich, pub. c.1830), in which he featured the duet “È ristoro a un cor che pena” from Caldara’s Santa Francesca romana (Rome, 1711) as a representative piece of its type.

Neapolitan composers were equally dedicated to the oratorio, and Nicola An-tonio Porpora (1686–1768) was particularly prolific in the genre. We know from the only surviving contemporary copy of the score (today housed in the Austri-an National Library in Vienna) that Il martirio di San Giovanni Nepomuceno (c.1730) was written for performance in Venice. The provenance and date of composition seem to be confirmed by the compositional style, which is very similar to that of works written by Porpora during his stay in Venice between 1726 and 1731, and are also supported by the circumstances of the canonisation of the eponymous saint in 1729 and his specific links with the Italian city. St John Nepomuk was particularly venerated not only in Prague (because of his Bohemian origins) but also in Venice, as the patron saint of rivers, bridges and boatmen. No copies of the original libretto have survived, but the score gives its author’s name as the “Marchese d’Este Santa Cristina”, now identified as Carlo Emanuele d’Este di San Martino (b. before 1703, d. 1766), member of a minor branch of the ruling house of Modena. The duet “Della fragile mia vita” is notable for its combination of academic counter-p oint and cantabile vocal melodies, as well as for its ingen-ious use of coloratura and ornamentation. This elaborate piece is a tribute to

10

the tradition of the chamber duet, but employs larger instrumental forces (the duets of Antonio Lotti, Carlo Luigi Pietragrua the elder and Agostino Steffani had continuo accompaniment only).

The second duet by Porpora included here, “Lascia ch’io veda almeno”, is taken from Il Verbo in carne (Naples, 1747), one of the rare Italian oratorios to tell the story of the Nativity (a religious feast that in Italy demanded sacred vocal music of an altogether different kind). This is another work of great mu-sicological interest. In my opinion, it was not written, as has previously been suggested, for either Rome or Dresden, but for Naples. This theory is backed up by the discovery of a printed libretto (part of the collection held by the library of the Società Napoletana di Storia Patria in Naples) which gives the author’s name as Giovanni Giuseppe Gironda (b. before 1708, d. 1753). The work’s Nea-

11

politan roots are also reflected in its portrayal of the Holy family, reminiscent of the kind of elegant Baroque Nativity scene typical of the region. Here, follow-ing on from some rather heated discussions about the fate of humanity, Justice and Peace find new hope as they contemplate the Christ Child in this lilting, galant minuet.

As proved by the excerpts heard here, although the Italian oratorio repertoire of the seven teenth and eighteenth centuries is little-known and rarely per-formed, it boasts a wealth of titles worthy of revival. I hope listeners will now be encouraged to discover more about this genre and the composers both familiar and unfamiliar who added to its riches.

Giovanni Andrea SechiTranslation: Susannah Howe

1 Al serto le rose Duetto di Regio fasto e Amor profano

Al serto le rose se unite agl’allori oh, come più belle m’appresta il valor.

E in cielo le stelle coi loro fulgori non sparser vezzose più lieto splendor.

Al serto etc.

2 Vaga rosa Aria di Agnese

Vaga rosa che fastosa nell’alba nutrì folle speme di vita immortale tosto langue che il raggio vitale Febo asconde all’occaso del dì; e disperse le pompe del crine fa di spine a l’estinta vaghezza il feretro, sia specchio un fiore a una beltà di vetro.

Quel ruscello, che rubello, sua cuna sprezzò sommergendo del prato i tesori, tosto manca ch’in seno di Dori la superbia dell’onde domò: e se lascia tra piagge tranquille, poche stille vivo raggio di sole l’adugge

Duet for Royal Pomp and Profane Love

If roses are entwinedin a wreath of laurel,oh, how their charmsadd to my courage.

And the stars in heavenwith all their radianceand beauty have castno more joyful a light.

If roses, etc.

Aria for Agnes

The lovely rosethat radiantlyat break of day cherishedthe foolish hopeof immortal lifesoon languishes, for Phoebushides his lifegiving rays at sunset;and when her lovely petals have dropped,he makes a coffin of thornsfor her former glory:let fragile beauty learn its lesson from that flower.

The little riverthat rebelliouslyoverflowed its bedand flooded the treasures of the meadowsoon disappears, for the nymph Dorishas tamed the sea’s proud waves:and if it leaves in its wake a few dropsbetween tranquil banks,they will dry up in the sun’s bright rays:

12

Duett des Königlichen Prunks und der Weltlichen Liebe

Durchwinden Rosenden Lorbeerkranz,oh, wie viel schönerstrahlt doch mein Heldenmut!

Die Sterne am Himmelverbreiten mit ihrem Schimmerbei aller Anmutkeinen schöneren Glanz.

Durchwinden etc.

Arie der Agnes

Die holde Rose,die, in voller Pracht,im Morgenrottörichte Hoffnungauf Unsterblichkeit hegt,verblüht, sobald Phöbus’ nährende Strahlenam Ende des Tages versinken;und liegen die Blütenblätter verstreut,bleiben nur mehr die Dornenauf der verblichenen Schönheit Bahre;drum ist die Blume der vergänglichen Schönheit Bild.

Der Bach,der rebellischseine Wiege fliehtund die fruchtbaren Felder überflutet,versiegt, sobald Dorisseine übermütigen Wellen zähmt;und die wenigen Tropfen,die am stillen Hang verbleiben,vertrocknen im Sonnenlicht;

13

sia specchio un rivo a una beltà che fugge.

3 Partite dolori Duetto di Donna prima e Donna seconda

Partite dolori, fuggite timori da un misero sen. Ch’al fine ridente la sorte clemente ci torna il seren.

Rie cure volate, affanni lasciate più libero il cor. Che vinto a la gioia, sbandita ogni noia, già cede il dolor.

4 Su l’arco d’amore Aria di Donna prima

Su l’arco d’Amore se posa mia sorte più chieder non so; fra dolci ritorte di nobile ardore, se un dardo vezzoso di fato amoroso la rota inchiodò, no, no, che al mio core bramar più non so.

Se servo al tuo piede si ferma il mio fato son paga così; d’Amor coronato se candida fede a questo mio seno un giorno sereno

let fleeting beauty learn its lesson from that river.

Duet for First Woman and Second Woman

Sorrows, begone,fears, vanish nowfrom this unhappy heart.For merciful fatehas smiled on us at lastand restored our peace of mind.

Evil cares, fly away,torments, allowthis heart to breathe more freely.For with every woe banished,sadness now yieldsto victorious joy.

Aria for First Woman

If my fate depends onthe bow of Love,I can ask for no more;if amid the sweet chainsof noble passiona charming arrowhas stopped the wheelof amorous fortune turning,no, no, my heart can desirenothing more.

If it is my fateto serve at your feet,that will satisfy me;if sincere faithhas finally grantedthis heart of minea time of peace

drum ist der Bach der flüchtigen Schönheit Bild.

Duett der Ersten und Zweiten Dame

Fort, ihr Schmerzen,flieht, ihr Ängste,aus dieser elenden Brust!Möge uns das Schicksalin seiner holden Güteendlich wieder Freude schenken.

Bange Sorgen, fliegt davon,ihr Nöte, lasstdas Herz wieder frei schlagen!Die Freude siegte,der Unmut verflog;schon schwindet der Schmerz dahin.

Arie der Ersten Dame

Liegt mein Schicksalin Amors Händen,so bin ich wunschlos froh;will in süßen Bandenedler Glutein anmutiger Pfeildas Los meiner Liebebestimmen,nein, nein – so kennt mein Herzkeine Sehnsucht mehr.

Ist es mein Schicksal,dir zu Füßen zu dienen,so bin ich selig fürwahr;schenkt reine Treuemeinem Herzennun endlichFrieden,

14

al fine scoprì, sì, sì, che in mercede mi basta così.

5 Aure voi de’ miei sospiri Aria di Inomenia

Aure voi de’ miei sospir fate l’eco a’ miei flebili lamenti; fra speme e timore ondeggia il mio core, e piangon l’errore i lumi dolenti. Aure voi etc.

6 Cor imbelle a due nemici Aria di Maddalena

Cor imbelle a due nemici come mai resisterà? Nel duolo instabile che il cor m’esanima non sa quest’anima, non sa gioire, languire non sa.

Cor imbelle etc.

10 Sempre fido, sempre grato Duetto di Esther e Assuero

Esther: Sempre fido, Assuero: sempre grato Esther: mio regnante, Assuero: mia salvezza, A 2: questo core a te sarà. Assuero: Dolce sposa, Esther: sposo amato la mia gloria, Assuero: il viver mio,

crowned with love,yes, yes, that is rewardenough for me.

Aria for Inomenia

Breezes, you take my sighsand make them echomy melancholy laments;my heart is caughtbetween hope and fear,and my sorrowful eyesweep at my wrongdoing.Breezes, etc.

Aria for Mary Magdalene

Defenceless heart, howcan you ward off two enemies?Caught in a conflict of painthat weakens my heart,this soul of minecan neither rejoicenor languish.

Defenceless heart, etc.

Duet for Esther and Ahasuerus

Esther: Always faithful, Ahasuerus: always grateful,Esther: my king, Ahasuerus: my salvation,Both: my heart will be to you. Ahasuerus: Sweet wife, Esther: beloved husband,my glory, Ahasuerus: my life,

von Liebe gekrönt,ja, ja, so ist’s mirLohn genug.

Arie der Inomenia

Ihr Winde, lasst die Seufzermeiner mattenKlagen widerhallen;zwischen Hoffen und Bangentaumelt mein Herzund meine schmerzenden Augenbeweinen meinen Fehler.Ihr Winde etc.

Arie der Magdalena

Schwaches Herz, wie willst duzwei Feinden widerstehen?In den Wallungen des Schmerzes,der mein Herz erdrückt,weiß meine Seeleweder zu frohlockennoch schmachtend zu vergehen.

Schwaches Herz etc.

Duett der Esther und des Assuero

Esther: Ewig treu,Assuero: ewig dankbar,Esther: mein Herrscher,Assuero: meine Retterin,Beide: wird dir mein Herze sein.Assuero: Süße Braut,Esther: geliebter Bräutigam,meinen Stolz,Assuero: mein Leben,

15

il mio ben, Esther: la mia grandezza, solo io deggio, Assuero: sol degg’io Esther: alla tua regal pietà Assuero: alla tua fedel pietà Esther: Sempre fido etc.

11 Si pensi alla vendetta Aria di Meraspe

Si pensi alla vendetta e il cor che m’ha sprezzato aspetti il mio rigor.

Amor più non m’alletta e l’animo agitato è pieno di furor.

Si pensi etc.

12 È ristoro a un cor che pena Duetto di Francesca e Angelo

Francesca: È ristoro a un cor che pena la speranza di gioir. Cara speme che diletti se tu vuoi che lieta viva dal mio sen, deh! non partir. È ristoro etc.

Angelo: È diletto a un cor che pena la speranza di gioir. Speme cara che diletti se tu vuoi che lieta viva dal suo cor, deh! non partir. È diletto etc.

my prosperity, Esther: my status,I owe solelyAhasuerus: I owe solelyEsther: to your royal mercy.Ahasuerus: to your loyal mercy.Esther: Always faithful, etc.

Aria for Meraspe

Let my thoughts turn to vengeance,and let the heart that spurned meexpect no mercy.

Love no longer entices meand my tormented mindis full of rage.

Let my thoughts, etc.

Duet for Francesca and the Angel

Francesca: The hope of joybrings solace to a grieving heart.Beloved hope, you who bring pleasure,if you want me to live in happiness,ah, do not abandon my heart.The hope, etc.

Angel: The hope of joybrings delight to a grieving heart.Beloved hope, you who bring pleasure,if you want her to live in happiness,ah, do not abandon her heart.The hope, etc.

mein HeilEsther: meine Herrlichkeitverdanke ich alleinAssuero: verdanke ich alleinEsther: deiner fürstlichen Gnade.Assuero: deiner treuen Gnade.Esther: Ewig treu etc.

Arie des Meraspe

Auf Rache will ich sinnen!Das Herz, das mich verschmähte,erwarte meine Strafe!

Nicht länger lockt mich die Liebe,und meine ruhelose Seeleist voller Wut.

Auf Rache etc.

Duett der Francesca und des Engels

Francesca: Labung ist dem leidenden Herzen die Hoff-nung auf Entzücken.Teure, frohe Hoffnung,willst du, dass ich glücklich lebe,ach, so schwinde nicht aus meiner Brust!Labung ist etc.

Engel: Freude ist dem leidenden Herzendie Hoffnung auf Entzücken.Teure, frohe Hoffnung,willst du, dass sie glücklich lebe,ach, so schwinde nicht aus ihrer Brust!Freude ist etc.

13 Lascia ch’io veda almeno» Duetto di Giustizia e Pace

Giustizia Lascia, ch’io veda almeno in questo bacio, o cara, depor la doglia amara il mondo vincitor.

Pace Torna di questo seno ai dolci amplessi, o bella, e si richiami quella placida età dell’or.

A 2 Che nuova guisa è questa di tenerezza e amor! A notte così chiara ceda coi raggi il sole, ceda alla bassa mole il ciel col suo splendor.

Giustizia Lascia, ch’io etc.

14 Quasi locuste Aria di Oreb

Quasi locuste che intorno l’ampio suolo ricoprono è quella gente che innumerabile qui d’Oriente venne a posar. Ed Israele d’essa all’incontro è come polvere che in mano chiudasi contra la rena che immensa i lidi

16

Duet for Justice and Peace

JusticeGrant that I may at least seein this kiss, o beloved,the victorious worldset aside its bitter pain.

PeaceReturn to the sweet embracesof this breast, o beauty,and let that peaceful, golden agebe recalled.

BothWhat new guiseof tenderness and love is this?Let the sun’s rays yieldto so clear a night,let heaven’s radiance yieldto the earth below.

JusticeGrant that, etc.

Aria for Oreb

The countlessswarms of peoplewho have come herefrom the easthave gatheredthick like locustsacross this land.And Israelwho would confront themis no more thana handful of dustcompared to the sandsthat cover all the immensity

Duett der Gerechtigkeit und des Friedens

GerechtigkeitLass mich zumindest sehen,o Teure, wie sie in diesem Kussden bitteren Schmerz begräbt,die siegreiche Welt.

FriedenKehre zurück an meine Brust,o Schöne, in meine süße Umarmung, und lass uns jenes stillengoldenen Zeitalters gedenken.

BeideWelch neue Gestalt der Zärtlichkeitund der Liebe ist doch dies!Solch heller Nachtbeugen sich die Strahlen der Sonne;der niederen Erde beugt sich der Himmel mit seinem Glanz.

GerechtigkeitLass mich etc.

Arie des Oreb

Wie ein Heuschreckenschwarm,der das weite Landbedeckt,ist jenes Volk,das zahlreichvon Osten herbeiströmt,um sich hier niederzulassen.Und Israel,vor seinem Angesicht,ist wie der Staubin einer Handgegenüber dem Sand

copre del mar Quasi etc.

15 Della fragile mia vita Duetto di San Giovanni e Angelo

San Giovanni Della fragile mia vita sino agl’ultimi momenti fra le pene e fra i tormenti io costante ogn’or sarò. O che sorte a me gradita sciolto poi dall’uman velo tuo compagno io goderò Della fragile etc.

Angelo Della fragile tua vita sino agl’ultimi momenti fra le pene e fra i tormenti tuo sostegno ogn’or sarò. O che bel trionfo in cielo sciolto poi dall’uman velo io godere ti vedrò

Della fragile etc.

17

of the sea’s shores.The countless, etc.

Duet for St John and the Angel

St JohnUntil the final momentof my fragile life,amid pain and torment,I shall always remain loyal.O how welcome a fateI shall enjoy as your companiononce I am freed from my human veil.Until the final, etc.

AngelUntil the final momentof your fragile life,amid pain and torment,I shall aways sustain you.O how sweet a victory in heavenI shall see you enjoyonce you are freed from your human veil.

Until the final, etc.

Translation: Susannah Howe

am endlos weitenMeeresstrand.Wie ein etc.

Duett des Heiligen Johannes und des Engels

JohannesBis zum letzten Augenblickmeines flüchtigen Lebens,durch alle Leiden und Qualen,will ich stets Treue bewahren.Oh, welch Schicksal ist mir beschieden!Befreit von meiner menschlichen Hülle,werde ich froh an deiner Seite sein.Bis zum letzten etc.

EngelBis zum letzten Augenblickdeines flüchtigen Lebens,durch alle Leiden und Qualen,will ich dir beistehen.Welch schöner Triumph des Himmels!Befreit von deiner menschlichen Hülle,werde ich dich frohlocken sehen.

Bis zum letzten etc.

Translation: Geertje Lenkeit

G010003525449C

![Guimares Rosa - Grande Serto Veredas[1]](https://static.fdocument.pub/doc/165x107/577d2f391a28ab4e1eb12383/guimares-rosa-grande-serto-veredas1.jpg)