Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

-

Upload

what-is-this-about -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 1/16

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Early Music.

http://www.jstor.org

Audible Rhetoric and Mute Rhetoric: The 17th-Century French Sarabande

Author(s): Patricia RanumSource: Early Music, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Feb., 1986), pp. 22-30+32-36+39Published by: Oxford University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3127596Accessed: 23-01-2016 23:28 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of contentin a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

This content downloaded from 90.48.197.33 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 23:28:35 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 2/16

Patricia Ranum

A u d i b l e r h e t o r i c n d

m u t

r h e t o r i c t h e

17th century

r e n c h s r b nde

. . .

. .

~2~c '>-ipaM/dC >-r

F

~

lnli- ?12?"

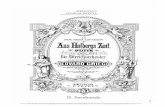

1 Danseurs de

Sarabande

from the Ballet des

quatre parties

du

monde

(Paris,

Bibliotheque

Nationale

19165;

photo

Giraudon)

In

1724

Jacques

Bonnet

categorized

the so-called

'Spanish'

sarabande

as an

unusually

expressive

ex-

ception

among

the

various

French

dances:

Almost

all the

dances that

are danced

at balls

and assemblies

employ

no

expression

i.e.

no

expressive

gestures],

with

the

exception

of

the

Spanish

sarabande

with

castanets,

or

the

English jig,

for the

courante

typifies

the

gravite

staidness]

of

French

dancing.'

In

singling

out

the

'Spanish'

sarabande,

Bonnet

implies

the existence

in the 18th

century

of a

'French'

sara-

bande

that

is less

demonstrative

than its Iberian

cousin,

which

steadfastly

retained

its castanets

and

expressive gestures

a

century

after

emigrating

to

France.

A mere

half

century

prior

to Bonnet's

reference

to

the

'Spanish'

dance,

sources

fail

to

mention

a staid

'French' sarabande.

Antoine

Furetiere's

Dictionnaire

universel

(1690), compiled during

the

1670s,

presented

an

exotic

Mediterranean

dance:

SARABANDE.

A

musicalcomposition, dance n triplemetre,

and which

usually

finishes

with a raised

hand when

beating

time,

in

contrast

to the

Courante,

which ends

with a lowered

hand. Like the

Chaconne,

the Sarabande

came from

the

Saracens...

It

is

usually

danced to the sound of the

guitar

or

castanets. Its

mouvement2

s

gay

and amorous.

GESTE.

he sarabande

employs

lascivious

postures

and

gestures.

It

was

'gay

and

amorous',

terms

that

implied

a

strong

22 EARLY

MUSIC

FEBRUARY

1986

This content downloaded from 90.48.197.33 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 23:28:35 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 3/16

undercurrent

of

seduction.

Indeed,

its

gestures-or

expression-were

'lascivious'.

In

addition, Furetiere

described

a

distinctive

sarabande

phrasing

that

moves

in full

bars,

a

phrasing

that stands in marked

contrast

to

that of

the

courante,

Bonnet's

quintessential

French

dance.

If,

as

late as the

1680s,

the sarabande

was

on the

surface Iberian and lascivious, a subtle change was

nonetheless

taking

place

in

the

lyrics

of

sung

sara-

bandes.

The distinctive balanced

phrasing

(ex.1a)

of

the

1640s

was

gradually

being

abandoned

in favour

of

the unbalanced

line

(ex.

1

b) preferredby

French

poets.

Exx.2and 3 show

the first of the

many

stanzas of two

sung

'sarabandes

or

dancing' published by

Jean

Boyer

in 1642.

(Phrasing

breaks created

by

the

mid-line

caesura or

by

the

rhyme

are

shown

in

all

examples by

the double slashes used

in

ex.1.)

Save for the con-

cluding pair

of

lines with their

hemiola

rhythm,

each

line

in

ex.2 ends at a musical

barline.

This

same

balanced,

assertive

phrasing

is

also found

in

'sara-

bandes for

guitar',

in

other

words,

for

'Spanish'

sara-

bandes.3

On the

other

hand,

ex.3

quickly

leaves this

balanced

phrasing

and

moves to the unbalanced line

that

typifies

the French

sarabande after

1690.4

Thus,

Ex.2(b)

1 Cloris,

-do

you-wish

to

know

The effect-of

your power,

Cleante-

night-

and

day

Burns-with love.

2 'Tis he-who-full-of trust

Within

his

soul

Cherishes-the flame

That he

nourishes-for

you.

Beware-lest his

eyes,

More

brilliant-than the

skies,

Should lose-their

clarity

Because of

your

beauty:

3 You read-his

passion

On his

visage

The

living image

Of

affection.

Will

sighs-and

tears,

The

proof-of

his

anguish,

Bring

an

end-to

his

life

Without

your help?

4

Must-the

charms

Of

a

heartless woman

In

addition to

pain

Cause-his death?

Ex. The

phrasing

f

sarabandes

(a)

a balanced

hrase

.

3 J J J IJ

J

J

I

J

JJ

(b)

an

unbalanced

hrase

3 ? ?

// 1 ii /

Ex.2(a)

ean

Boyer,

Sarabande

our

danser',

Ie

ivrede chansonsa

danser

t d boire

Paris,

642),

.36v

A

•e

r

r0,0

; I

1

M

I

Clo-RIS,

I

VEUX

-tu sa-VOIR //

L'ef-FET de TON

pou-VOIR//

(Cloris,

do

you

want

to know The effect of

thy power,)

A

,

Cl

-

an

-/te

nuit /

et

JOUR

(//)Brfi-//le

d'A

-

MOUR //

(Cl~ante

night

and

day

Burns

with

love:)

C'EST

luy

/

qui

/

PLEIN

/

de FOY//

De

-

DANS

son i

-

me//

('Tis

he who full

of trust

within his

soul,)

Che

-

rit

/

la

fl

-

me//

Quil

NOUR-rit

/

POUR TOY//

(Cherishes

the

flame

That he nourishes

for

thee.)

Clo-RIS,

VEUX-tu sa-VOIR

/

L'ef-FET

de TON

pou-VOIR,

/

Cle-an-

/

te

nuit

/

et

JOUR

/

Brfi-

/

le

d'A-MOUR.

/

C'ESTuy / qui / PLEIN de FOY/

De-DANS

son

a-me

//

Che-rit

/

la

fla-me

//

Qu'il

NOUR-rit

POUR

TOY.//

PRENDS

ar-

/

de

que

SES

YEUX

/

PLUS

bril-LANTS

que

LES

CIEUX

/

VONT

per-

/

dre

LEUR

CLAIR-TE

/

POUR

a

BEAU-TE:

/

Tu

lis

/

sa

pas-si-ON

//

DANS SON

vi-sa-ge,

//

Vi-van-te

i-ma-ge

//

De

l'af-fec-ti-ON.

//

LES

sou-PIRS

et

LES

PLEURS,

//

Te-MOINS

de SES

dou-LEURS,

//

Fi-ni-RONT-ILS SES

JOURS

//

SANS TON

se-COURS?

/

Faut-il

/

que

LES

ap-PAS

/

D'u-ne

in-hu-mai-ne,

//

Ou-tre la

pei-ne,

//

Don-

/

nent le

TRES-PAS?

/

EARLY

MUSIC

FEBRUARY

1986

23

This content downloaded from 90.48.197.33 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 23:28:35 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 4/16

by

the

1660s,

the

Spanish

sarabande,

a

recent

immi-

grant,

had

to some

extent

already

adapted

to the

manners of

the

French

court. It was

abandoning

the

assertive

phrasing

of its

native

land for

the

more

tender

verse

structure of

its

adopted

country.

In so

doing,

it

abandoned none

of its

expressiveness.

In

1671 Father

FranqoisPomey

included a

definition

of

the

sarabande

in

his

French

and

Latin Dictionnaire

royal,

first

published

at

Lyons.

This

Jesuit

teacher of

rhetoric

agreed

with

the

academician

Furetiere,

and at

the same

time added

several

important

details:

SARABANDE,

altatio

numerosa,

quam

arabanda

ocant

[a

metred

dance

that

they

call

the

sarabande].

he

sarabande

s a

passionate

ance hat

originated

ith

he Moors f Grenada

and that the

Spanish Inquisition

outlawed because it

deemed

t

capable

of

arousing

ender

passions,captivating

the heart

with

he

eyes,

and

disturbing

he

tranquillity

f the

mind.

ForPomey the sarabande was 'Spanish',and so lewd

that

it was

outlawed

by

the

Church.

Like

Furetibre,

he

considered

the

metre

of

a

sarabandeso essential to its

character that

he

gave

the dance the

Latin

name

Saltatio

numerosa.This 'metre' is

not,

however,

the

rhythm

created

by

the

double slashes of

phrase

and

half-phrase,

but the

rhythm

created

by

'number',

hat

is,

by

the

way

crotchets

are

placed

within

those

larger

units

in

groups

of

one,

two,

three or four notes.

Indeed,

the

larger

phrasing

does not

preoccupy

Pomey. During

this

period

of

transition,

he does not address the

question

of

whether

the dancer

moves to the balanced

phrasing

of ex.2 or the unbalanced one of ex.3. His

chief

concern

is the

passionate

nature of this

'Spanish'

dance.

The lascivious

gestures

and

postures

of

the sara-

bande did

not

prevent

the Jesuit

pedagogue

from

dwelling

at

length

upon

this

dance. A detailed

bilingual

'Description

of a Danced

Sarabande',

written

between

1664

and

1671,

was included in an

appendix

to

Pomey's

dictionary.5

The French

ext

appears

as illus.4.

The

description

will

be

analyzed

at

length

later

in

this

article.

(A

transcription

of

the French

original,

with

English translation,

can

be found on

page 35.)

Song

and dance

as

oratory

Pomey's precious

document confirms

the

presence

of

what some

considered

to be lascivious

postures

and

gestures

in the

mid-century

sarabandein

France. It

also

provides

sufficient information

to

permit

some

study

of

the dance as a

unitary experience,

that

is,

a

study

not

only

of

the notes and

lyrics,

but

of

gestures

Ex.3

First

stanza

of

Belle

riviere,

another

'Sarabande

pour

danser'

by

Jean

Boyer,

IIe

livre de

chansons

a

danser et

a

boire

(Paris,

1642),

f.37v

I.

1

1

'

i

,ImI

',

Bel

-

le

ri

-

vi

-

re,

/

SUR

qui

/

na

gu6

-

re//

(Lovely

river,

on

whom

long

since)

Phi

-

LIS

I

jet

-

TOIT

/

SES

DOUX

re

-

GARDS

//

(Philis

cast

her

sweet

glances]

A

*

-0"

1.

1

-f;•a

aI.

r

'

"

POUR BIEN

PLEU

-

RER

(//)

I'ab-men

CE//

de

SES char

-

mes,//

(To

greatly

mourn

the absence

of her

charms,)

A

_,,-L-

,-1..-]

I

Tu AS MOINS

/

d'EAU//que

je

n'au

-

ray

/

de

lar

-

mes.//

(You

have

less water

than I

shall have

tears.)

as

well,

in the

light

of the

rhetorical

theory

of the

period.

The

analysis

of

all these dimensions

is

inspired

by

numerous statements

in

rhetoric handbooks

of

the

period,

which liken dance

steps

to

the

individual

syllables

of

a

song,

the

complete

lyrics

of that

song

to

an

oration,

and

the

actor's

expressive

gestures

to

the

orator's

figures

of

speech.

For

example,

in 1702 Michel

de

Saint-Lambert

compared

a

piece

of

music to an oration

and sub-

divided

the musical

composition

into smaller

units

that he

equated

with

the sections

of

a

speech.6

And,

indeed, the lyricsof 100 selected dance songs written

between 1619

and

17507

leave

little

doubt

that the

train of

thought

in a French air

assumes the

four-part

organization

of

a

speech

described

in

the

various

rhetoric

handbooks.8

(These

four

parts

are

marked'l,

2,

3

and

4' in the

examples

to this

article.)

This

same

four-part

division

is evident

in

Pomey's

description

(illus.4),

where

each

section

of the

dance

is

separated

from the

next

by

a

space.

That

the

mute

rhetoric

of the

dance

and the

audible

rhetoric

of the

singer

are both

founded

upon

the

principles

of

public speaking

is confirmed

by

com-

paring

the

wording

of

Pomey's

definition

'Sarabande',

quoted

in full

earlier,

with

the

definition

of the

'Art

of

Rhetoric'

by

his

contemporary,

Rene

Bary.

Bary

wrote:

'Rhetoric

is a

discipline

that

reveals the means

of

persuading,

moving

and

pleasing.'9

The

orator's

goal

is

threefold.

He must

persuade

his audience

or,

to

use

another of

Bary's xpressions,

'unsettletheir

minds'.A

consummate

actor,

he must

move his listeners

by

24

EARLY MUSIC

FEBRUARY 1986

This content downloaded from 90.48.197.33 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 23:28:35 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 5/16

Ex.4

Jean-Baptiste

Lully,

Sarabandedes

contrefeseurs',

Ballet

de

la raillerie

(1659;

F-Pn,

Vm6

4,

p.71)

1.

2+4//4//

A.

EN-FIN

/

je

VOUS

re-VOIS,//

CHAR-man-te

COUR//

(At

last

I see

you

again, Charming Court, )

2.

1+3//3+2//

LIEU/

TANT

ai -

ME

/ Ou

na -

quit/

l'a

-

MOUR//

(Place

so beloved where was

born the

love)

2

+

Que

j'ay/POURCli -

m

-

ne//

(That

I bear

Climine.

)

S.

3+5

//5/

..

I

Et

je

VOIS

/

de

-

PUIS MON

re-TOUR//Que

cet-te

in-hu

-

mai

-

ne

//

(And

see

since

my

eturn

That

his

nhuman

ne)

I

Com-me le pre- MIER JOUR EST IN-SENsi-ble

(As on

the first day

is

insensitive)

a

ma

pel

-

ne.//

(to

my pain.

)

portraying

on

his

face

and

registering

in

his

voice

the

emotions

he

wishes his

audience

to feel in

earnest.10

Andfinally, he must pleasethem

by

the

'regular'

and

'agreeable'

rhythms

of

his

speech,

a

rhythm

that

he

continually

varies

according

to

the mood

he

wishes to

create.

The

dancer is

confronted

by

a

similar

challenge.

He

too

must

persuade

his

audience,

or,

in

Pomey's

words

(which

closely

resemble

Bary's)

disturb

he

tranquillity

of

the mind'.

Like

the

orator,

he

must

move

his

audience

and 'steal

hearts

by

his

glances'.

He

also

pleases

onlookers,

forhis dance

is

'metred',

numerosa;

and

it is metre or 'number'

Fr.:

nombre, adence;

Lat.:

numerus)

hat make

a dance

agreeable.'2

Thus,

by

definition,

both the dancer

and the

orator

set

out to

persuade,

to

move,

and to

please

their

audiences.'3

In other words,

they

both

employ

the

art

of rhetoric.

They

sharetheir reliance

upon

this artwith

the

singer,

who,

at least

as

early

as Mersenne,

was

described as

a

'harmonic

orator'.'4

Before

turning

to

the

English

translation

of

Pomey's

Description';

et

us

look

more

closely

at these three

facets of 1

7th-century

rhetorical

theory,

in order to

recognize

them in

the

audible rhetoric

of four harmonic

orators,

and

in

the

mute rhetoric

of

Pomey's

male

dancer.

'Persuading,moving

and

pleasing'

Persuasionwas accomplished chiefly by the orator's

skilful use

of the so-called

'figures'

of

speech.

Hand-

books describe

the orator as locked in

something

of

a

combat

with his listeners

from his

opening

statement.

He must convince

them

by

his

artful

deployment

of

exclamations,

questions,

dramatic

pauses,

repetitions,

strongly

contrasted

statements,

exaggerations,

and

so

on.

As Bernard

Lamy,

another

contemporary

f

Pomey's,

pointed

out:

'These turns

of

phrase,

which are

the

characteristics

traced

by

the

passions

during

speech,

are the famous

figures

to

which

rhetoricians

refer.'"

Thus,

figures

of

speech

express

the

passions16

hat

the

orator s actingout andhopes to stir n the hearts ofhis

listeners. In

other

words,

figures

of

speech

not

only

persuade,

they

also move

the

audience.

These

figures

of

speech

are the

verbal

equivalents

of

certain

postures

that the

body

assumes

when

seized

by

strong

emotions:

Allthe

figures

of

speech

naturally

mployed

when

excited,

create

the same effect

as the

postures

of

the

body;

as

postures

are

appropriate

or

protecting hysical

hings,

so

figures

of

speech

can

conquer

r

nfluence he

mind.

Words

are the soul's

spiritual

weapons."7

Although they

'protect

physical things', postures

and

gestures

are

by

extension

the

soul's

physical

weapons.

Through

posture

and

gesture,

the

mute

rhetoric

of

dance,

painting

and

sculpture

stirs

the

passions.

Specific

postures

and

facial

expressions

that

hadbeen

observed

as

typical

of

certain

emotional

states

were

called

upon

to

reproduce

these

emotions in

stone

and

on

canvas.

8

On

the

stage,

in

the

pulpit,

and

before the

bar,

hese

same

postures

and

expressions

accompanied

EARLY

MUSIC

FEBRUARY

1986

25

This content downloaded from 90.48.197.33 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 23:28:35 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 6/16

the verbal

figures

of

speech.

For

example,

while

uttering

the

repeated

exclamations,

'No

no ..

.',

an

actor or orator would

assume the

posture

associated

with

the

passion

called 'aversion'.He would

step

back-

wards or

at

least

lean

away

from his audience and

would extend his arm toward

them,

the hand at

right

angles

to the arm and the

palm exposed.'9

He would

also

avert his

eyes,

to show 'aversion'.

The audience takes

pleasure

n

the

regularity

of

the

orator's

phrasing,

that

is,

in

his

observance

of the

lengthened

syllables

and the

pauses

that end each

carefully

planned

clause of

an

oration.20

The same

pauses-shown

by

double

slashes

in

our

examples-

were

employed

in

oratory,

verse drama and

operatic

airs,

in love

songs, drinkingsongs

and

dance

songs.

As

the

lyrics

of these

examples

show,

balanced

phrases

go

hand-in-hand with

assertive,

exclamatory

state-

ments,

while unbalanced

phrases

usually

express

tender,plaintive thoughts-or implyhemiolas. Since

the ear

easily

picks

out these

contrasting phrasings

and the emotions

with which

they

are

associated,

the

position

of the double

slashes within each four-

measure

phrase

is

of

prime

importance

to the rhetoric

of the

sung

sarabande.

Although

the

rhythm

of these

pauses

determines

the

general

mood of each

line,

this

largerphrasing

is

not

the stuff of

which

strong passions

are made. Rhetoric-

ians

pointed

out

that,

although

sentences should

always

employ

a

regularlyrecurring

rhythm

of

pauses

at

the

end of each

clause,

the

rhythms

of the

smaller

grammaticalunits should 'perpetuallyvary'.2' ndeed,

it is

through

these smaller

units that the

passions

are

portrayed

n

speech

and verse. In other

words,

within

the

relatively

inflexible structure of

poetry

and the

very

inflexible

musical metre to which that

poetry

is

set

(both

described

n

detail

by Rosow),

French

Baroque

poets

varied

speech

rhythms

from line to

line,

accor-

ding

to

the emotions

they

wished to

stir.

These

passionate

rhythms

combine with

the

figures

of

rhetoric to create the

'character',

he

'movement',

the

mood

of a

speech,

a

song

or

a

dance.

These

rhythms

are

determined

by

three factors: the

length

of

the

individual

syllables,

the number of

syllables

in a

group,

and

the melodies of emotional

speech;

the first

two

will

be discussed here.22

Familiarity

with these

passionate speech rhythms

is essential to an under-

standing

of the

sarabande,

for statements in 17th-and

18th-century

treatises liken the

rhythmic

units of

speech

to the

steps

of a

dance,

and

Pomey's

dancer

seems to have been

drawing

a similar

analogy.

2 A

Spaniarddancing

the sarabande at

the

opera:

engraving byNicholas Bonnart,

cl685

Passionate

rhythms

In

this

article the term

syllable

length

is not

synony-

mous

with

the shorts

and

longs

of

poetic

scansion.

Instead,

it

means the

short

and

long

syllables

'of

declamation' that

Benigne

de

Bacilly

summarized

in

his handbook

of

1668.23

That is to

say,

the

'long

syllables'

discussed

here are the

long,

sustained

sounds

of French

oratory.

Bacilly

and

his

successors

are

unequivocal:

a

long syllable

must be

made

to

seem

'long',

despite

the

inadequacies

of

musical notation.

The

length

of the

syllable

therefore

overrides

the

position

of its

note

within a

musical bar.

In

other

words,

a

long

syllable

on the

final note

of a bar must

seem

long

to the ear. It

should not be

neglected

as if

it

were an

embarrassing

error

by

the

librettist,

simply

on

the

grounds

that it

occupies

a

weak

position

in

the bar

or

is a

candidate for the

rhythmic

alteration

of

notes

26

EARLY

MUSIC FEBRUARY 1986

This content downloaded from 90.48.197.33 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 23:28:35 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 7/16

inegales.

(These

long

syllables

are

shown

in

capital

letters

throughout

the

examples.)

The number of

syllables

in

a

group

is

of

prime

importance

to

French declamation of the

passions.

These

groups,

or

rhythmic

units,

are set off

by

single

slashes

throughout

the

sung

dances

in

this article.

Rhythmicunits are not synonymous with the metric

feet of standard

poetic

scansion. French

Baroque

poetry

s

based

upon

units of from one to six

syllables,

each

ending

with a

pair

of

lengthened

syllables (which

in

many

cases are

also

long

syllables

of

declamation).

On the other

hand,

the

classical feet

of

scansion lack

one-, four-,

five- and

six-syllable

units.

This discre-

pancy,

combined with the

pair

of

lengthened

syllables

at

the

end of each

rhythmic

unit,

prompted

numerous

Baroque

writersto insist that

applying

classical

scan-

sion to

French was an

anachronism,

an exercise

in

antiquarianism.24

The shorter a French rhythmic unit, the more

intense it

appears

in

comparison

with

surrounding

units. One- and

two-syllable

units are therefore

per-

ceived

as

containing

key

words,

and their

syllables

are

intuitively

lengthened.

(Readers

will

note that

many

of

these short units

are,

in

addition,

made

up

entirely

of

long

syllables,

and

that

they usually

express

the

key

ideas of the

song.)

These short units are

employed

in

exclamations and commands.

Three-syllable

units are

perceived

as

balanced

and calm. Units of four

syllables

and more

approach

what could be called the

fluid,

'unsustained'

style

of conversation or of

hasty,

emo-

tional remarks.

Short

rhythmic

units

of one or two

syllables

are

capable

of

overriding

he accents of

musical

metre

and

the

end-accentuation

described

by

Rosow. That

is,

a

one- or

two-syllable

unit

employed

in

early-

or mid-

line

(especially

if its

syllables

are also

long

or on

a

raised

pitch)

will

attract

the

listener's attention

from

the end-accents at caesura

and

rhyme(heureux

n

ex.6),

on occasion

creating

the effect of

a

displaced

double

slash

(Brile

in

ex.2,

and

labsence in

ex.3,

with its

long

and

expressive

lyric

e).25

Syllable lengths

and

rhythmic

units combine

in

various

ways

to create the

rhythms

of

the

passions.

A

run

of

long

syllables,

especially

if

broken

into short

units,

makes a

speech

seem

to move

slowly.

A run

of

short

syllables

in

long

units is heard as

movingrapidly,

while

a

unit of

similar

length

with numerous

long

syllables

seems

dragged

out and

suspenseful.26

Shifts from

one

passion

to another

are often re-

vealed

by

a series

of words with 'feminine'

endings,

that

is,

words

that

end with

a

mute e.

(The

penultimate

long

syllable

of these

words is shown

in

bold face

type

in

the

various

examples.)

As the

single

slashes

and

bold face

type

in

lines 3

and 4

of ex.2

show,

this mute

e

is heard as

starting

a

new word or a new

rhythmic

unit

and crosses

the

slash like a

wave,

rising

to

a

crest

before sinking to the soft 'uh' of the e.27This gliding,

connected

rhythm,

often

employed

to

evoke

flowing

water

(ex.3),

appears

chiefly

in

insinuating, cajoling,

flattering

passages

of

songs

and

recitative.

In

its

extreme

form,

the

penultimate

syllable

swells like a

great

wave and adds

pomposity

to the

speech

of

kings,

to evocations

of the

gods,

or to

exaggerated

remarks.

These,

then,

are

the

passionate

rhythms

that create

the

'movement'

of

a French

Baroque

dance

song.

They

'move'

the

audience

by

arousing

a

variety

of

passions,

and

they

create

the effect of

changing

the

'tempo'

at

which

the words are

sung

within the inflexible

musical

beat.Theyare the keyto the performanceof all French

Baroque

music,

for

they

are

inseparable

from the

figures

of

speech

and the

body

gestures

of the

art of

rhetoric.

Indeed,

Pomey's

dancer mimes these

speech

rhy-

3 An

orator

speaking

before

an

oratorical

academy.

engraving

by

Sebastien Le

Clerc,

1680

EARLY

MUSIC FEBRUARY

1986 27

This content downloaded from 90.48.197.33 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 23:28:35 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 8/16

thms,

perpetually

varying

the

rhythms

of

his

steps.

As

the'movement' of his

passions

increases

or

wanes,

the

rhythms

these

passions

stir

within him are

reinforced

by

his

gestures

and his

facial

expressions,

much

as the

important

syllables

of

a

French

song

are

strengthened

by expressive

articulation and

lengthened

vowels.

In

addition,

from time

to

time he

mimes with his

body

the

rhetorical

figures

of

speech.

Ex.5 Andre

Campra,

Air

pour

une

Espagnole',

sung

between

repetitions

of an

instrumental

sarabande,

L'Europe

alante

(Paris,

1698), .152

1. 2

+2//4//

A

+

SO

-

yez

/ CON

-

STANTS. //

DANS VOS

a

-

MOURS,

//

a-

(Be

faithful.

In

your

love,

//

Lov-

4

3

2+3+3//

M A N T S

E S T

P R E S T

-

ers,

one

is

ready

to

surrender;)

8 4

5

2.

2+3/3//

+

...

...

.

N

COEUR /

QU'ON

at

-

ta

-

/que

TOU

-

JOURS//

(A

heart

that

is attacked

always)

6

6 o

2+2+4//

+

I1

Se

la-/

seEN-

FIN

/

de

se

def

- fen

-

DRE:

//

(Wearies at last

of

defending

itself:)

I

.

4

3

3.

1

+ 2

+

2+3//

12

1

+

-DRE: TOST

/

ou

TARD

/

ii VIENT/D'HEU-REUX

JOURS//

(Sooner

or later

come

happy

days)

4.

3+3//

a

qui

SCAIT/LES

at

-

ten

-

DRE.//TOSTOU

-DRE.

To he who knows how to wait.

)

The

following presentation

of

Pomey's

Description

of a

Danced

Sarabande'

co-ordinates

this

dancer's

mute oration

with

pertinent

statements

from

rhetoric

handbooks

and with the audible

rhetoric

in the four

sections of four

dance

songs.

Exx.2a

and

2b serve

as

our model

for the rhetoric

of

sung

sarabandes

early

in

the

century. (Ex.3,

which

represents

the

opening

statement of

a

multistrophed

song,

is

excluded

from

this

analysis.)

Exx.4,

5 and 6

carry

the sarabande

throughLully

and

into

the 18th

century.

This

emphasis

upon

oratory

does not

imply

that

musicians

studied

rhetoric

in

exclusive

secondary

schools,

the better

to

'orate'

their

performance.

Nonetheless,

composers,

singers,

instrumentalists

and dancers

alike

were suffi-

ciently

acquainted

with the

rules of that

art to

apply

them to

performance.

Pomey's

'Description': 1)

The Exordium

Accordingto rhetorical theory, an oration generally

has four

parts:

an

introduction,

an account

of the

matter

being

discussed,

a

presentation

of

the

pros

and

cons,

and

a

concluding

statement.

The

introduction,

or

exordium,

erves

as a

prelude

to the

body

of

the

speech,

setting

the mood:

'Musicians

use

preludes

to

prepare

the

listener's

ear,

actors use

prologues,

and

orators

use exordiums.28

Here

the

orator

should

speak

gently

and

peacefully

on

a rather low

pitch.

His

face

and

gestures

should

be

restrained,

modest

and

slow.

He

should not

gesture

with his

hands

until

he has

uttered several

sentences.29

In dance songs of all types, the exordium usually

takes the form

of

a statement

addressed

to

a

specific

audience:

in

our

examples,

Cloris,

overs,

and so on.

In

the exordiums

of

most

sung

sarabandes

written

be-

tween

1642

and the

1730s,

'slow'

two-syllable

units

with numerous

long

syllables

predominate.30

For

the

earlier

part

of

this

period,

they

are assembled

into

a

balanced

phrasing

(exx.1

a, 2,

3 and

4). By

1700

the

unbalanced

French

phrasing

predominates

(exx.

b

and

6),

although

the

virtually

abandoned

balanced

phrasing

occasionally

resurfaces

(as

in

the

song

by

a

Spaniard

n

ex.5).

Pomey's

dancer

mimes

the

salutation of the exor-

dium

by

assuming

the

dancer's

equivalent

of

the

imposing

posture

that

17th-century

artists

give

an

orator

who

is about

to

speak.

(A

monarch

or a

general

stands

with one

arm

down

athis

side,

the other

crossed

over his

chest.)

Like

the

orator,

the

dancer

completes

his

greeting

before

bringing

his hands

into

play

and

assuming

the

orator's

posture

portrayed

by

Sebastien

28

EARLY

MUSIC

FEBRUARY

1986

This content downloaded from 90.48.197.33 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 23:28:35 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 9/16

Le

Clerc

in 1680

(illus.3)-a

posture

similar

to

that

shownin

18th-century

dancebooks.3I

His

step

rhythms

imitate

the orator's

speech

rhythms.

To

the

balanced

phrasing usually

employed

in

this section

until

1690,

he

moves

with

an

'equal

and

slow

rhythm'

hat

inspires

respect

and

gives'pleasure'.

(See

paragraphs

1]

and

[2].

References

to

step rhythms

are italicized

throughout

the Englishtranslation.)

(2)

The

Narration

Having

set

the tone

in these

opening

remarks

and

impressed

his

audience

by

his

bearing,

the

orator

moves

to the

second

part

of

his

speech,

the narration

f

the

point

he

wishes

to

make.

Handbooks

advise

him

to

predict

dire

events

if

his

warnings go

unheeded.32

Any

figure

of

rhetoric

used in

this

section

should

be

emphatic

(e.g.

an

exclamation),

and

'his

voice

and

gestures

should

fit

the

subject

and

the

figures'.33

Increasing

emotion

should

not,

however,

lead

to

vehement

speech

or

exaggerated

gestures

this

early

in

the

oration.

Instead,

the

orator

should

add

emphasis

by

introducing

a

new

speech

rhythm

and

tone

of

voice,

at the

same time

moving

his

hands

more

expressively

than

before.34

These

suggestions

were

heeded

by

the

versifiers

of

the

four

dance

songs.

In

ex.2

the

singer

predicts

a

catastrophe,

while in

ex.6 he

exclaims. In

dance

songs

of all

types,

the

speech

rhythms

of

the

narration

usually

differ

noticeably

from

those

of

the

exordium.

For

example,

a

series

of

feminine

endings

is

often

set

to a melody that on paperresembles another section

(exx.2,

text,

and

5).

For

more

than

a

century,

sara-

bandes

employ

increasingly

longer

units

as

the

dance

progresses,

usually

shifting

to

three-syllable

units in

the

narration. In

other

words,

the

singer

seems

to

be

increasing

the

speed

of

his

words

as

his

emotions

heighten.

This

increased

emotion

often

goes

hand

in

hand

with

erratic

rhythms

in

both

lyrics

and

music.

Thus,

ex.4

expresses

its

passion

through

a

unit

set

to

quavers

that

takes

the

form

of

two

extra

bars

inserted

between

the

usual

four-bar

phrases.

Instead

of

adding

measures,

the harmonicoratorof ex.5 omits one, whilethe singer

in

ex.6

pours

out

his

emotion

in

alternating

dotted

crotchets

and

quavers.

Pomey's dancer

seems

aware

of

these

rhetorical

conventions.

He

restricts

his

hand

and

torso

motions,

concentrating

upon

the

rhythms

of

his

feet.

He

glides

rather

han

steps,

blurring

his

footwork

as

if

miming

a

run

of

feminine

endings,

where

the

divisions

between

Ex.6

Marin

Marais,

Sarabande

pour

une

prestresse',

Alcione

(Paris,

1706),

p.163

1. 1

+

3

//2+2

+

2//

+

+

DIEU/

ES

a-MANTS,//HEU-REUX/ui

ENT

TES

fl

-

mes

(God

of

lovers,

happy

he

who feels

thy

fires)

Sa

L

3.

4//4

+2//

(da

-drea

ng

Nil

.o)

ohingu

ldsh

witehouttthey;)

exclamation

in

ex.6.-

tres

BIENS//N'ENdchancer

then

flies

off

with

es

Oapparently

miming

the

apossession

called

'aversion'

or

##4

4.

1+1+1+2+2//

+

+

NON,

/

NON, /

RIEN

/netPLAnST/SANS

TOY

aI

(No,

No,

nothing

pleases

without

thee.)

rhetorical

figures,

as

he

costruggles

o

'unsettering

he

exclamatiminds'

f

his

audienex6.

he

and,

y

the

n flies

offf

his

section

'destroy

their

obstepsinacy'.

t one

pointmake

is

argumentscks

p,

'strontaneity

nd

invincible',

he

employ

his

movexaggerated

igures

hat

into

he

second

section

of his

speech,

the

orator29

rhetorical

figures,

as

he

struggles

to

'unsettle

the

minds'

of

his

audience

and,

by

the

end

of this

section,

'destroy

their

obstinacy'.

To

make

his

arguments

'strong

and

invincible',

he employs

exaggerated

igures

This content downloaded from 90.48.197.33 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 23:28:35 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 10/16

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 11/16

Nicolas Poussin

(c1594-1665).

Dance

to

the Music of Time

(detail)

London,

Wallace

Collection.

32

EARLY

MUSIC FEBRUARY

1986

This content downloaded from 90.48.197.33 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 23:28:35 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 12/16

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 13/16

equivalent

f the 'oratorical'

nd

pathetic

ccents'

that

s,

the

pitch

accentsor

long

syllables

hat

so often

fall onweak

notes of the

musical

measure].46

This observation

may

well

provide

a tool for historians

of the dance.

The

lyrics

of

sung

sarabandes indeed confirm

that

within the larger structure of 'end-accentuation',

speech

rhythms

and their emotional connotations

convey

the

passions

of a dance to the audience.

In like

manner,

we

know from Diderot

that,

within the

larger

structure of

reposes

in

a

dance,

tiny

differences

in

footwork,

posture

and

gesture

permitted

he dancer to

express

the emotions associated with

a

given

dance. It

remainsfor dance historians to discern

these'pathetic'

figures

and

gestures

concealed within the

arabesques

of

18th-century

choreographies.

I am

grateful

o

Betty

Bang

Mather

or

the

many

insights

into the

performance f

French

Baroque

dances that she

shared with

me.

I

also wish to thank

Professors

Henri

Morier

f

Geneva,

van

Fonagy

of

Parisand

Joseph

Pineau

of

Poitiers

or

their

helpful

orrespondence

nd kind

words.

M.

Morierhas in addition

reatly acilitatedmy

work on

French

Baroque

declamation

by offering

me

materials

from

his

laboratory.

The

many

unremuneratedours

he

spent

marking

ach

syllable

of

meter

upon

meter

f

oscillo-

gram

print-outs

re

deeply

appreciated

am

especially

n-

debted

o

William

Christie nd all the

members

f

'Les

Arts

Florissants'

or

their

encouragement,

heir

udicious

obser-

vations

and their

willingness

o test

my

findings.

Patricia

M.

Ranum

is

a

researcher nd

translator

rom

Baltimore,

Maryland

DIVERSES DESCRIPTION S.

III*

%L

Di•'cription

'une

Sarabande

danse&.

1

danTa

one

abord,

aur

wne

ra

u

sw

wfaIt

thbar

nate,'

rr

n

ar

grv

awflrdamerdena

te

4

St

ntc

P

ave

toM

mer

.

corps

i'Se,qb

6ji.f

iorI

C" ii

a ti,

qM'i

rut toume

4

ma'Wfl

an

'

y

.

R

'il

Win#j

r-,

pma

mwuns

e

mr#B,

quual

ama

dt

plAjir.

Ea

t•ire,

'ilevawt

uavre

s

da

diGl041tin

ortant

lei

ra,

i

demy

hats,

a

d y

eaerjt

fi

4

s

5

b#Aw.xpaOue

'.P

O

aj]

s

am"nuse

ear

dmf.pox

Tau:tefl

u

ie fteu blementfan qe

r..

PAtdif.

Str

&

meoovemr

do

(rsprwdi

de

fes Umess

&fembloit

Plrtoji

gsljfrqu

sMurc:

:

Trntofto vec

I~s

ply'. ka4x

temps

I

monodc,il emwreaoitr

ndu.,

im•mo•itd

.

i

de.-

mp

dr..

d'be

ord,

a

ve

de

wfpied$

Cn

fres :

C

sid

p4ra1t

la

perr

1,I

aV*i.tfiure

d'unecadane ,

par

meo

awre

ps

prci

ri•

,

on

Ie

vooet

prrIt

u

vP

lr

,

stm

eSA

moPrIment Jloiseapide.

Tantojf

i1

U

anfoit ea

A

petits

bonds

taOteft

retloi:t grands

pA

qyua

w

rg.M

. q

Im•s

t

tetent P4.A

voiJfoent

efirefait,

fs

art

,

sAws

tI eu bimr

rcA•kU

se

ienscul

afWgisgenUe.

TaNtO.ll

pose

r

laehriet

pAr

tt,

i f

tesnuui

A

droit,"t

fm/I

re s$i

u..

•ACrfr&gil

w

~

ao pijue

milieude

1eacecOUiUdZI

uJ

ajser

te

dons

w.Asomem

ifla

,ui

slrm

yeur

am

1pwiS

Beyueupf~

ltlibtr

p

reedence

mtm

.rs

r

o

"ft

isl

dfirdso

pparsir

s'il

l

iP.

Wei,

Lre.ser

eursgluear

pfefeuua

awqwv4-te#?Mr

jos uswuireas

o~p.r

LOMinds

*oswuem

jhrl

Wia/e,

dAs

f-sy,

8Mfx

Fas

e

sMesfs

rT

Me

Ldfdes

wgads

I ai.

,a7s

que r., SU

AN,

gasst

P,~~la

a

vr

d- f

a-s

P

isw0-r-a

par

dAes

se6h

dinv

vris

r,

Fit

s

mr.

oasu

ea

s

.

'm

adh

III.

Defcriptio

altatienis mnMrof~a,qitv

dg)

Sarabanda

dik'twr.

S

A'tationem

igicur

autp1cartus

tt

cum

almiratione

fpe-

J

lantium,

ravitcr

primuin

c

ctfiiun,

quablialcnt6.

quc

matu.

tamcirti,

tamn

nuuitc,

cam

dcoid,

clqtuec

czpcudt Ic

mnvchcnv,

ut

q'ocut.lu

e fc

a

ct,

r[iIam

circlmt"rrct

maj.ltatcm

.

nec

vCeclratiossil

min?is

CGC-

cuaret,luacm

obieattnniaffidJcrct.

l'olt

p'. ,0

:0ani,

ahquan1l

mags

C

cincitans,

bra-

htaquc

soilhl

a

t,)'.lcs

.

acquc

nonmhd

tplcauos

alrus

dcbt

initabilcs

c

fltupcndos.

Nunc

decntc.gradu

Cc

pe

finleenCu

nferebat,i

ana

tam

int9'di,quaun

c,

pcr

lubr cunm

gere

idcrctur,

Au

l

v.ltigi• •

I.

abcntc

planti.

Nunc

morulis

Gamla

cum

vcnaltte

intcriccls,morum

cermatchbat

ait~qua,

tip'ernmintus

&

nchin.ins

in

latus

alrcrum,lhccoult

p.nlo pycic

D:.n

jadaram

qufi

compnlfans

m~Id

tCInpoL1u,

mcIndabat

,.cttarlct

calditatem

morC

adeC

rapido

Itdruan

ctnctlcns ut volatumpotLWRc

qjainexrccre

ltatrationem.

A..i,quafi

modctC

u'filins,

c6iidn(fquepovhet.

bat

fict; magnts

lias

alslipbasrtrcdcbat

,'tats

illUs

qui1cem

cz

aris

formuli

,

fed

Club

artilicil

fuL*

celat

attcm,tum maxiue pcodcbat,es ocultaIu idiofit

V

Nunc

qu6

voluptatem

circunquaque

rcfperg

ret,

a

in

omnem

parem•aquabili~rdirpcntrct

oblek&ama

tum,

verabat

Cc

mod6

dczttn dm,

mod6liRuriftwni

aque

ubim

medium

vCeraS=

,

in

iugym

ira

pa

cipitam

fe

voIvebat,

ut

coporis agilitcaem,

loeIma aclentas

minimr

pofec

afflqui.

In:elrum

nenounquam,

fdibus

intared

oacinenti

bus,

clabi

numcrumfiicbat Rtazu

ad

ipitat procs

immotus moe exrreasc dacnctic,a revlui

qtoc.

qucns

n moium

jactliIt,

xcrm

tu

vidchbP

aual

parne,

clm

nonduim

fc

moviffe

loco

crede•trr.

cAm,

hand

quaqam la

magam

aciida

,

p

illis

quz

(iunt

onutafccucrnum

mos vadelicet

mimt

motu

apit homadmilendu

yvarioexhibec

opowis

mocuS

a

vuiaocmlii

UwcfhabaLquIc

ct.o,

co•s

przlnx.

Nuclanguidluos

adjiciebat

ac

illcocules,cupid,.

tapis leaos&anmos ndices,quaadi&angure vide-

barturi

cant sTumn

quA edi

arus

atatp

p1gdcr. iuaitdi

4r

t

culmini al6,

elruteamn

animum

coucitatenueafe

amritan,•quam

iacratIi

CiM,

tu,

gratiam

u re

ita

b

ncbalbs.

AliqaW4n1,taundivi_

indito•.t~ian•tq

,

iphi

o

nto

morcsba

t

.cf

:lqumaon:d&ura:

twm

Cpum

CIptunCS

modcSatiore

fahateI

,

frumpii

vidcba•uut kct,

ddbtui

vidbusapimoddtnqui -

guentancr

ntfquc oculoscircumwtcere

mnlti-ri

deu

mu

covcrfionvclac

ontorfionc

tAchiorum

corp.

Xis,

Pw)c

ClcrS

fluflc

rnifCi.

nuoc

pmrturbari

roje"

&torum

tanu•t.

pepmit

fibi

rimartionis

a&

tix,

utquadrlu

ptiti~atUl

hrzc

Sa•tatio

enuit

omni•nm

tcuuett

mnimos

amoredcvin&'aoquonua

oculos

vo,

1uptac

c

ucgataImi•ationc

.4.xos.

4 Father Francois

Pomey.

'Descriptiond'une Sarabande

dansee': Le dictionnaire

royal

augment6 (Lyons,

1671). p.22

(Bibliotheque

municipale.

Rodez;

photo

R. and

P.

Lancon)

34

EARLYMUSICFEBRUARY

986

This content downloaded from 90.48.197.33 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 23:28:35 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 14/16

Description

'une

Sarabande

ansee

[1]

Ildansa

donc

d'abord,

vec

unegrace

outd

aitcharmante,

d'un

air

grave

&

mesured

'une

adence

gale

& ente&avec

un

port

de

corps

i

noble,

i

beau,

i

libre,

&

i

digagd,

u'il

ut oute

la

majest6

'un

Roy,

&

qu'il

n'inspira

as

moins

de

respect,

u'it

donnadeplaisir.

[2]

En

suite,

s'dlevant

vec

plus

de

disposition,

&

portant

es

bras

d

demy

hauts,

&a

demy

ouverts,

l

fit

les

plus

beaux

pas

que

l'on

ait

jamais

inventez

pour

la

danse.

[3]

Tantost

il

couloit

insensiblement,

ans

que

l'on

pzit

discer[ner]

e mouvementde

ses

pieds

& de ses

jambes,

&

sembloit

pli2tost

lisser

que

marcher:

antostavec

les

plus

beaux

emps

du

monde,

l demeuroit

uspendu,

mmobile,

&

d

demypanchi

d'un

cdte,

avecun

de ses

pieds

en

I'air:

&

puis

reparant

a

perte

qu'ilavoitfaite

d'une

cadance,

ar

une

autre

plus precipitie,

n le

voyoitpresque

oler,

antson

mouvement

estoit

rapide.

[4] Tantostlavanfoitcomme

d

petitsbonds;antost l reculoit

d

grandspas; qui

tous

reglez

qu'ils

toient

paroissoient

stre

faits

sans

art,

tant il

estoit

bien

cache

sous

une

ingenieuse

negligence.

[5]

Tantost

pour

porter

a

felicitM

ar

tout,

l

se

tournoit

droit,

& tantost

l

se

tournoit

d

gauche;

&

lorsqu'il

stoit

au

juste

milieu

de

l'espace

vuide,

il

y faisoit

une

piroiette

d'un

mouveme[n]t

i

subit,

que

celuy

des

yeux

ne

le

pouvoit

uivre.

[6]

Quelquefois

l

laissoit

passer

une

cadence

entiere ans

se

mouvoir,

on

plus

qu'une

tatue;

&

puis

partant

commeun

trait

on

le

voyoit

d

'autre

bout

de la

sale,

avant

que

'on

eust

e

loisir

de

s'appercevoiru'il

estoit

parti

[7] Maistoutcelanefutrien, ncomparaisone ceque 'onvit

lorsque

cette

galante

personne

commenfa

d'exprimer

es

mouvements e

l'ame

par

ceux

du

corps,

&de

les

mettreurson

visage,

dans ses

yeux,

en ses

pas,

& en

toutesses

actions.

[8]

Tantost l

lanfoit

des

regards

anguissans

&

passionnez,

tant

que

duroit

une

cadence

lente

&

languissante;

&

puis

comme

e

lassant

d'obliger,

l

ddtournoit

es

regards,

omme

voulant

acher

a

passion;

&

par

un

mouvement

lus

precipitd,

il

diroboit

a

grace

qu'il

avoit

faite.

[9]

Quelquefois

l

exprimoit

a

colbre

& le

depit par

une

cadance

mpetueuse

&

turbulente;

&

puis

representant

ne

passion

plus

douce

par

des

mouvemens

lus

moderez,

n

le

voyoitsotpirer,epmer, laissererrerses eux anguisamment;

&

par

de

certains

ddtours

e bras

&de

corps,

onchalans,

emis,

&

passionnez,

lparutsi

admirable

tsi

charmant,

ue

tant

que

cette

Danse

enchanteresse

ura,

l

ne

deroba

pas

moins

de

coeurs,

qu'il

attacha

d'yeux

d

le

regarder.

[1]

At first

he dancedwith

a totally

charminggrace,with

a

serious

and

circumspect

air, with

an

equal

and

slow

rhythm,47

nd with

such a noble, beautiful,

free and

easy

carriage

hat

he had all the

majesty

of

a

king,

and

inspired

as much respect as he gave pleasure.

[2]

Then,

standing

taller

and more

assertively,

and

raising

his arms

to

half-height

and

keeping

them

partly

extended,

he

performed

the most beautiful

steps ever

invented for the dance.

[3]

Sometimes

he would

glide

imperceptibly,

with

no

apparent

movement

of

his feet and

legs,

and seemed

to

sliderather

han

step.

Sometimes,

with

the most

beautiful

timing

in the world,

he would remain

suspended,

mmobile,

and half

leaning

to the

side with one

foot in the

air;

and

then,

compensating

or

the

rhythmic

unit

that had

gone by,

with another

more

precipitous

nithe would

almost

fly,

so

rapidwas his motion.

[4]

Sometimes

he would

advance

with little

skips, some-

times he would

drop

back

with

long steps

that,

although

carefully

planned,

seemed

to be done

spontaneously,

so

well had he cloaked

his

art in skilful

nonchalance.

[5]

Sometimes,

for the

pleasure

of

everyone

present,

he

would turn

to the

right,

and

sometimes he

would turn

to

the left; and

when he reached

the

very

middle

of

the

empty

floor, he would

pirouette

so

quickly

hat

the

eye

could not follow.

[6]

Now and then

he would

leta whole

rhythmic

nit

go

by,

moving

no morethan

a statue and

then,

settingoff

like

an

arrow,he would be at the other end of the room before

anyone

had

time to realize

that he had

departed.

[7]

But

all this was

nothing

compared

to what

was

observed

when

this

gallant

began

to

express

the

emotions

of his soul

through

the motions

of

his

body,

and

reveal

them

in his

face,

his

eyes,

his

steps

and all

his

actions.

[8]

Sometimes

he would

cast

languid

and

passionate

glances

throughout

slow

and

languid

rhythmic

unit;

and

then,

as

though

weary

of

being

obliging,

he

would

avert

his

eyes,

as if

he

wished

to

hide his

passion;

and,

with

a

more

precipitous

motion,

would

snatch

away

he

gift

he

had

tendered.

[9] Now and then he would express angerand spite with

an

impetuous

ndturbulent

hythmic

nit;

and

then,

evoking

a sweeter

passion

by

more

moderate

motions,

he

would

sigh,

swoon,

let his

eyes

wander

languidly;

and

certain

sinuous

movements

of

the arms

and

body,

nonchalant,

disjointed

and

passionate,

made him

appear

o

admirable

and so

charming

that

throughout

this

enchanting

dance

he

won as

many

hearts as he

attracted

spectators.

EARLY

MUSIC

FEBRUARY

1986

35

This content downloaded from 90.48.197.33 on Sat, 23 Jan 2016 23:28:35 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/25/2019 Rhetoric 17thC French Sarabande Ranum EM 1986

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/rhetoric-17thc-french-sarabande-ranum-em-1986 15/16

1J.Bonnet,

Histoire

endrale

de la danse sacree et

prophane Paris,

1724), p.69.

Although gravit6

can

also be rendered

as

'slowness'

or

'seriousness',

Bonnet

is

contrasting

the emotional excesses

of

the

sarabande with the

propriety

of

the

other dances.

2Although

mouvement eferred

o

both

'motion'

(or tempo,

metre)

and

'emotion',

the latter

translation

is

generally

the

more

appro-

priate.

It

is not

a

question

in

Furetiereof

an

'amorous

empo',

but

of

a

dancer

who tries to

'move' his

audience to feel

gay

and amorous.

This emotion

is to a

large

extent

conveyed by

the

rhythmic

movement of the upper voice. On these rhythms,see J. Pineau,Le

mouvement

ythmique

n

franfais

(Paris,

1979).

3The

music

has,

unfortunately,

been lost: J.

La

Mesnardiere,

Les

poesies

(Paris,

1666),

pp.48,

69,

112.

4This

phrasing

was

already

well established

by

the

1660s,

witness

the

music-less

lyrics by

P.

Perrin,

Les

oeuvres

de

podsie Paris,

1661),

pp.255,

257;

and

Bouillon,

Les

oeuvres

de Feu Monsieur

de Bouillon

(Paris,

1663),

pp.

183,

217,

218.

5In

his

'Avis au

Lecteur',

Pomey

states

that he

has

been

accumulating

materials

for this

appendix

for 'six or seven

years'.

Although

omitted from

this

article,

the