GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

-

Upload

cleitonlages -

Category

Documents

-

view

225 -

download

1

Transcript of GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

1/78

EPA

Recycled/Recyclable Printed on pper that contains at least 50% reccled fiber.

United States Solid Waste and EPA530-R-92-026Environmental Protection Emergency Response August 1993Agency (OS-305)

Household HazardousWaste ManagementA Manual for One-DayCommunity Collection Programs

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

2/78

This handbook is designed to help communities plan

and operate a successful household hazardous waste

(HHW) collection program. The handbook focuses on

one-day drop-off programs. Other types of HHW collection

programspermanent, mobile, and special-are not discussed

in detail.

The handbook is intended for community leaders and HHW

collection program organizers. It provides guidance for all as-

pects of planning, organizing, and publicizing a HHW collec-

tion program. It does not provide technical information about

the treatment, disposal, or transport of HHW. These jobs are

performed by professional contractors or others with special-

ized training. The manual includes information about select-

ing a qualified hazardous waste contractor

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

3/78

Household HazardousWaste Management

A Manual for One-DayCommunity Collection Programs

Section 1

Section 2

Section 3

Section 4

Section 5

Section 6

Section 7

Section 8

Section 9

Section 10

Section 11

Appendix A

Appendix BAppendix C

Appendix D

Page

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ...1

Getting Started . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ...5

Selecting Wastes and Collection Methods . . . . . . . . . .11

Selecting Waste Management Methods . . . . . . . . . . .17

Minimizing Liability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ...21

Funding the Program and Controlling Costs . . . . . . . . .25

Publishing the Request for Proposals andSigning the Contract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ...31

Selecting, Designing, and Operating the

Collection Site . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ...37

Training the Collection Day Staff . . . . . . . . . . . . . .41

Education and publicity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ...45

Evaluating the Program . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ...49

Case Studies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ...51

Hazardous Waste Laws and Regulations . . . . . . . . . . .58

State and Regional Hazardous Waste Contacts . . . . . . .62Information Resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ...68

Sample Participant Questionnaire . . . . . . . . . . . . . .74

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

4/78

What Is Household once the consumer no longer has any use for

Hazardous Wast e?them. The average U.S. household generatesmore than 20 pounds of HHW per year. As

Many common household products con- much as 100 pounds can accumulate in the

1

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

5/78

I N T R O D U C T I O N

home, often remaining there until the resi-dents move or do an extensive cleanout.

Hazardous waste is waste that can catchfire, react, or explode under certain circum-stances, or that is corrosive or toxic. The

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency(EPA) has set stringent requirements for themanagement of hazardous waste generated

by industries. Some HHW can pose risks topeople and the environment if it is not used,stored carfully, and disposed of properly.However, Congress chose not to regulate it

because regulating every household is sim-ply too impractical.

Government and industry are working todevelop consumer products with fewer orno hazardous constituents. However, forsome products, such as car batteries and

photographic chemicals, no safe substi-

tutes exist. So, communities will need effec-tive HHW management programs for sometime to come.

Communit ies FindSolutions

HHW programs can benefit communitiesin several important ways. They can reduce

the risks to health and the environment re-sulting from improper storage and disposalof HHW. They can reduce communitiesliability for the cleanup of contaminationresulting from improper HHW disposal.Finally, HHW programs can increase com-

munity residents awareness of the potentialrisks associated with HHW and promote a

ommon Household Hazardous Wast

(These i tems, and o thers not i nc luded on th i s l i s t , m ight conta in mater ia l s

that are i gn i tab le , cor ros i ve , reac t i ve , or tox i c . )

qDrain openers

qOven cleaners

qW and metal cleaners and polishers

qAutomotive oil and fuel additives

qGrease and rust solvents

qCarburetor and fuel injection cleaners

qAir conditioning refrigerants

qStarter fluids

Paint thinners

Paint strippers and removers

Adhesives

Herbicides

Insecticides

Fungicides/wood preservatives

Source: A Survey of Household Hazardous Wastes and Related Collection Programs, Office of

Solid Waste and Emergency Response, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. EPA/530-86-038.

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

6/78

1990

1991

175

2 4 8 31 94

1988 1989

I N T R O D U C T I O N

PROGRAMS

1 ,000

800

600

400

200

0

better understanding of waste issues ingeneral.

Many communities have established pro-grams to manage HHW. The impetus forstarting a HHW program can come from the

grassroots level, from local or state gover-nment agencies, from community groups, orfrom industry. The number of HHW collec-

tions in the United States has grown dramati-cally over the last decade. Since 1980, whenthe first HHW collection was held, morethan 3,000 collection programs have beendocumented in all 50 states.

Although programs vary across the coun-try, most include both educational and col-lection components. Communities usually

273

1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986

YEAR

300

L1987

484

859

802

693

umber of HHW Collection Programs in the United States, 1980-1991.

ourceWaste Watch Center, Andover, Massachusetts, 1991.

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

7/78

N T R O D U C T I O N

begin a HHW program by holding a single-day drop-off HHW collection. Organizing acollection event is an important first step inreducing and managing risks associatedwith HHW.

Some communities hold annual or semia-nnual collections, while others have estab-lished permanent HHW collection programswith a dedicated facility (open at least onceeach month) to provide households withyear-round access to information and reposi-tories for HHW. By 1991,96 permanentHHW collection programs were operating in

16 states. In addition, communities haveinitiated pilot programs for curbside pick-up

by appointment, neighborhood curbside col-lection programs, and drop-off programs forspecific types of HHW.

The efforts of communities across thecountry provide a wealth of experience forother communities beginning HHW manage-ment programs. As the number of these pro-grams continues to grow, public awarenessabout HHW will also grow, and the environ-mental problems associated with improperstorage and disposal of HHW are likely to

decrease.

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

8/78

Getting Started

5

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

9/78

G E T T I N G S T A R T E D

Planning for your first HHW collection must begin very early-as long as 6 to 18months before a projected HHW collection date. See box for a sample timeline for

planning the HHW collection. In addition, the case studies presented in Section 11describe how two communities successfully planned HHW collection days.

Define Roles and

Responsibil i t iesAlthough one person can be the catalyst

for beginning a community program, thesuccess of the program depends on the in-volvement of a variety of individuals andorganizations. A key initial step in planningthe program is identifying who should beinvolved and defining their roles andresponsibilities.

The PlanningC ommi t t ee

The most important step in beginning aprogram is enlisting a core group of peoplewho can assemble the needed resources andmanage the program. The planning commit-

tee can perform or oversee many differentfunctions, such as:

Providing background information.Setting policy and goals.

Obtaining finding and other resources.Championing the program in the

community.Supervising a sponsor.

The process of forming a planning com-mittee can begin at a meeting of communityofficials and interested members of the pub-lic where they can discuss instituting aHHW management program. Telephoninginfluential community members and placing

announcements in the local media can helpboost attendance at the meeting.

If sufficient support for a program exists,

the people gathered can choose a programcoordinator, form a planning committee andsubcommittees, and begin planning the pro-gram. The planning committee usually in-

cludes solid waste, health, public safety, and

planning officials; legislators; members of

citizen groups; and representatives from lo-cal business and industry.

The HHWProgram Sponsor

Every community HHW managementprogram needs a sponsor or co-sponsors.

Usually the sponsor is a government agency,but some programs are sponsored by a civicorganization or a business. The sponsorsrole includes:

Managing and funding all aspects of theprogram.

Developing Requests for Proposals(RFPs) and contracts with a licensed

hazardous waste contractor.

Recruiting, managing, and delegating re-sponsibilities to supporting agencies andstaff.

s Involving community leaders and resi-dents in planning and implementing the

program.

The HazardousWast e Firm

Most communities contract with a quali-fied hazardous waste firm that handles theHHW at the collection site and brings it to ahazardous waste treatment storage, and dis-

posal facility (TSDF). If you hire a hazardous

waste contractor to handle the HHW collec-tion, be sure to choose a firm or firms licensed

to store, transport and dispose of HHW ac-cording to federal and state requirements. Haz-

ardous waste contractors might not need tobe fully licensed (see Appendix A) to per-form the duties your contract requires.Licensing, however, helps to ensure that the

contractor is experienced. The roles of the

6

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

10/78

G E T T I N G S T A R T E D

contractor are spelled out in the contract and

can include:

Providing necessary materials and

equipment.Properly training its collection staff.

s Obtaining necessary insurance.

Consulting with the program plannersabout waste management methods to beused.

s Providing necessary services on collec-tion day, such as unloading wastes fromvehicles; screening, packaging, testing,

and labeling wastes; supervising volun-teer personnel; and hauling and dispos-ing of the waste.

s Complying with all applicable federal,state, and local requirements.

s Submitting post-collection reports.

s Identifying appropriate hazardous waste Information on selecting a contractor is

TSDFs. provided in Section 6.

6 to 18 Months before Collection Identify/order equipment

Establish planning committeeArrange disposal and recycling of

Identify program goalsnonhazardous material

Select program sponsor and cosponsors brought in

Contact environmental regulatory Continue education and intensify

agencies publicity efforts

Begin designing education program Solicit volunteers

Initiate community outreach Acquire insurance

Research laws, regulations, and guidelines Develop collection day surveys

Determine collection methods

Set tentative collection date(s)0 to 6 Weeks before Collection

Select potential sites Receive equipment and suppliesInitiate public education program Conduct worker training/safety training Determine targeted wastes/excluded Complete publicity campaign

wastes/generators Confirm police/emergency serviceEstimate costs involvementSecure funding

Issue Requests for Proposals (RFPs) Collection Day

to S Months before Collection Set up site

Evaluate RFP submissionsOrient community staff and volunteers

Interview contractorsComplete participant questionnaires

Select contractorqReceive, package, and ship HHW

Identify markets for reusable andClean up site

recyclable HHW Post-Collection DayInvolve emergency services (fire,police, etc.) Tabulate survey responses

Begin publicizing collection program Evaluate collection/public education

Obtain permits results

6 to 12 Weeks before CollectionPublicize results

Thank participants and volunteers

Design site layout and draw site plan through the media

Develop collection day Write summary report

procedures/written plan Prepare for future events

7

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

11/78

G E T T I N G S T A R T E D

Involve theC o m m u n i t y

Community involvement is critical to thesuccess of a HHW management program.

Government agencies, community groups,local legislators, businesses, industries, andconcerned citizens should be involved fromthe start. They can promote the HHW pro-

gram in a number of ways:

Bu i ld ing accep tance fo r t he p rog ram

If key community leaders participate in

the planning process, they can help buildcommunity acceptance and support for theproject. In addition, local officials will know

the mood and interests of the communityand can help avoid or overcomesensitive issues.

Develop ing a sense o f commun i t yownership

People involved in planning and imple-menting a project will feel that the programbelongs to them. Community ownership

helps to ensure greater participation on col-lection day as well as community prideabout the outcome of the event.

Prov id ing communi ty ass is tance

Volunteer groups and residents often can

contribute expertise or resources and canshare the responsibilities of planning andimplementing the program withthe program sponsor.

8

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

12/78

Prov id ing leadersh ip on HHW issues

The more community leaders learn about

managing and reducing HHW, the morelikely they will be to support an ongoing orpermanent program. Many community lead-

ers also will alter their buying and disposalpractices, becoming examples for the com-munity.

Assemble the Fact s

Members of the planning committee

should conduct background research duringthe programs early planning stages. At least

a month or two is needed to acquire the in-formation necessary to plan the program and

inform the community. This research can beconducted by planning committee members,

who can provide important information in

their own areas of expertise:

Health department officials can pro-

vide technical data (such as materialsafety data sheets) about specific hazard-

ous materials.Police and safety officials can provideprocedures for handling materials and

for preventing and managing accidents

(such as site selection procedures andtraffic management).Legislators and public officials can

provide relevant regulations and

guidelines.Public interest groups can provide site

selection considerations, media con-tacts, informational materials, and proce-

dures for volunteer recruitment.Businesses can provide information

about sources of funding and material

and equipment donations.Educators can provide curricula and

audiovisual materials.

It is essential that the sponsor and the

planning committee learn about the federal,state, and local regulations that apply to

their HHW management program as well as

the steps they can take to minimize liability.It is important to note that state regulations

9

G E T T I N G S T A R T E D

might be more stringent than federal hazard-

ous waste management regulations. For ex-ample, states might require HHW collectionprograms to obtain operating permits. Local

governments also might have applicable re-

quirements, such as zoning laws or buildingcodes. These issues are discussed in Section4 and Appendix A. The sponsor or planning

committee should review current literature,attend conferences or workshops about man-aging HHW, if possible, and contact the

state hazardous waste management agency,

the EPA regional office, and local agencies(see Appendix B).

It is also important to anticipate the types

of wastes to be collected, since different

types of HHW present different transportand handling requirements. The type of ac-

cumulated HHW is strongly influenced bywhether the community is in an urban, sub-

urban, rural, or agricultural area. For exam-ple, an agricultural area might generate largequantities of pesticides. Pesticides areamong the most expensive wastes to dispose

of. HHW programs in rural or agriculturalareas, therefore, might be more expensive

than programs in urban or suburban areas.

Collection programs in environmentallyproactive communities usually will have

higher participation and collection rates thanprograms in less environmentally active

communities.

Establish Goals

Every HHW management program needs

clear, realistic goals and feasible ways of

achieving them. Typical program goalsinclude:

s Maximizing public participation. By

maximizing participation in the HHW

program, the quantity of hazardous ma-terials will be reduced in both the solidwaste stream and the wastewater

stream. Greater participation will mean

higher costs for the community in theshort run but will help avoid or reduce

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

13/78

G E T T I N G S T A R T E D

costs associated with potential environ-mental cleanups. It will also help to pre-vent or minimize health and safetyproblems associated with improper

HHW storage and handIing in homes.maximizing the reuse and recycling

of HHW. By maximizing reuse and re-

cycling, program sponsors will mini-mize their hazardous waste disposalcosts and will conserve natural and fi-nancial resources. Collecting productssuch as paint for reuse and recycling,

however, might result in higher laborcosts (e.g., for paint consolidation). Inaddition, communities will have to lo-cate and secure markets for the materials.

s Removing from homes those wastes

considered most hazardous. Instead ofcollecting all wastes, some communitiesmight want to collect specific wastes

that they consider to present an unac-ceptable risk or to be a likely source of

environmental contamination, such asoil-based paint and used motor oil. Itmight be difficult, however, to educatepeople to bring only those wastes to thecollection. In addition, environmental,health, and safety problems could

result from uncollected wastes in thecommunity.

9Educating the public about reducing

generation of HH W. Some programsponsors might want to establish a

HHW program to provide informationto consumers about proper HHW man-agement and alternative ways to reducegeneration of HHW. No matter how ef-fective education is, however, collectionprograms will still be needed for wastes

for which there are no alternatives (suchas car batteries) and for existing HHWstored in homes.

Identifying goals will help collection pro-gram organizers determine the basic type ofcollection program (e.g., periodic drop-off,curbside, or permanent), the amount of fund-

ing needed to collect and manage the wastes

and to educate the community about the pro-gram, and the waste management practicesthat the program will use.

10

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

14/78

Selecting Wastes

and Collection

Methods

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

15/78

S E L E C T I N G C O L L E C T I O N M E T H O D S

wDecide

hen initiating a collection program, the planning committee must decide who

may bring wastes to the collection, what types and quantities of waste will be

accepted, and how the waste will be collected.

W h o

May Bring Wastesto t he Col lect ionProgram

Most collections are limited to wastes

generated by individuals at home and ex-

clude hazardous waste from commercialand institutional generators. This is primar-

ily because programs are expensive, aver-

aging $100 per participant. In addition, bylimiting the number of participants it is

possible to limit the amount of wastes (al-

though it also reduces effectiveness).

Some HHW collections, however, are

open to small businesses that are condi-

tionally exempt small quantity generators

(CESQGs) of hazardous waste (see Appen-

dix A). Examples of businesses and institu-

tions that might be considered CESQGs

under certain circumstances include flo-rists, home repair businesses, gas stations,

and schools. CESQGs often are unawarethat they produce hazardous waste, and so

sometimes store and dispose of wastes im-properly. A HHW program that includes

these generators can educate them about

environmentally sound ways to manage

their hazardous waste. Requirements that

must be followed if a HHW collection pro-

gram accepts wastes from these small busi-

nesses are explained in Appendix A. Thesegenerators usually are charged based on

the cost of managing their wastes. The

charge for CESQG waste is less than whatgenerators would pay if they managed the

waste themselves.

Dec ide What Types

Of HHW to Accept

The two types of waste received mostoften at HHW collections are used motor oil

and paint. Pesticides usually are the thirdlargest category. Programs also receive sig-nificant numbers of car batteries. Over thenext few years, the types of wastes collected

might begin to change, and the volume ofcertain types of HHW will probably de-

crease. For example, the proportion of latexpaint compared to oil-based paint will prob-ably increase since sales of oil-based painthave been decreasing. It will take a long

time, however, to remove stored materialsfrom all the homes in a community. (In SanBernardino County, California, for example,

the paint brought to HHW collections is an

average of 10 years old.)

To minimize costs, some programs tar-

get only specific recyclable HHW, such asused oil, car batteries, antifreeze, and latex

paint. In addition, HHW collections oftenexclude certain wastes that the contractor

is not licensed to receive or does not havethe necessary equipment to identify or han-

dle. Certain wastes also might be excludedif the TSDF will not accept them. Fre-

quently excluded wastes include garbage,

asbestos, dioxin-bearing wastes, explo-

sives, radioactive such as smoke detec-

tors, and unlabeled or unknown wastes.Most programs also exclude medical

wastes. In New Jersey, however, some pro-grams have begun to collect medical waste

using a hauler licensed to handle suchwastes.

12

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

16/78

Decide Whether to Limit the Amount Of HHW

A few programs limit the amoubt of HHW that each participant may bring to the collectopn. For example, some collections

impose a five-gallon or 50-pound limit per participant, while others limit the size of the containers. This practice holds down

collection-day costs. Limits can also prevent CESQGs or small quanity generators (SQGs) (see AppendixA) from bringing

wastes to the collection, if that is a goal of the program. In some states, limits on the amount of HHW are set by law. In addition,

state permits for one-day collections or program contracts may forbid overnight storage of the hazardous waste. Amounts, therefore,

might need to be limited so that all wastes can be properly packaged before the end of the day.

Programs accepting waste from small businesses (CESQGs only) might limit amount acepted ro charge a participation

fee so that the program will not be overwhelmed by disposal costs. Allowing dropoff "by appointment only" will prevent the

collection site from being overwhelmed by too many CESQGs.

S E L E C T I N G C O L L E C T I O N METHODS

Select a Col lect ionMethod

To maximize participation, many commu-nities are experimenting with a variety ofcollection methods. Some use a combination

of collection methods. Common collectionmethods include one-day, permanent facil-ity, mobile facility, door-to-door pickup,

curbside, and point-of-purchase. Althoughthis manual focuses on one-day drop-off pro-grams, the next section briefly introduces

each of the major types of HHW collectionprograms.

One-Day Drop-Off

Most communities begin HHW programs

with one-day, one-site events at which resi-

dents drop off their HHW. The events usu-ally are scheduled in the spring or fall;participation during other seasons is limitedby summer vacations and winter weather inmuch of the country. One-day drop-off col-lections typically are held on Saturday, with-out appointments, starting in the morningand ending in the afternoon.

A potential limitation of drop-off pro-grams is finding a date for the collection onwhich the hazardous waste contractor will

13

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

17/78

S E L E C T I N G C O L L E C T I O N

be available. It is important to confirm the

date with the contractor as early as possible(six months in advance is recommended), es-pecially if HHW collections are scheduledon the weekend. Weekend HHW collectionsin the spring and fall are very popular, and

these dates fill up quickly.

Another potential limitation of one-dayprograms is that the chosen day might notbe convenient for some residents. To ad-dress this concern, some communities holddrop-off collections on more than one dayfor example, a Saturday and Sunday-or on

two successive weekends. The selectedHHW collection date(s) should not conflictwith other major events in the community.

Holding collections in more than one loca-tion within the community also can increaseparticipation.

Still another potential limitation is that

participants sometimes must wait an hour ormore to drop off their wastes. Organizers of

drop-off collection events need to plan waysto avoid long waits. Strategies for reducingwaiting time include using express lanes forcertain wastes (see Section 7), holding thecollection in several different locations,holding the collection over several days, andimplementing a two-phase program (for ex-

ample, accepting paint and oil one day andother wastes the next).

Permanent Drop-Off

I f the limitations of one-day collectionsprove too great, a community might want toconsider instituting a permanent drop-off

program. The community must anticipate anumber of needs that accompany permanentdrop-off programs, including:

Managing the increased annual quantityof HHW and increased participationrates.

s Ongoing public education and publicity.s A facility for onsite storage of HHW.

s

s

M E T H O D S

Training local staff to perform many of

the responsibilities usually assumed bythe hazardous waste contractor atone-day collections.An institutionalized, predictable fundingsource.

Compliance with additional state and lo-cal regulatory requirements that mightapply to permanent programs.

Permanent programs require a larger up-

front investment than one-day collections,but they probably will reduce costs per par-ticipant for the community in the long run.For example, communities generally usetheir own employees instead of contractors,often resulting in lower costs.

Drop-Off at aMobi le Faci l i ty

Most surveys show that the average col-lection day participant travels five miles orless to the site. Sponsors can purchase a mo-bile facility and equipment to provide peri-odic collections on a regular schedule atdifferent sites within a county or large com-munity. This is an effective method for pro-

viding service to geographically large anddiverse regions. Like permanent programs,these mobile collection programs might costmore than one-day programs in the begin-ning, but they probably will reduce costs perparticipant over the long term.

Door-to-Door Pickup

Door-to-door pickup by appointment is

expensive, but it is more convenient for par-ticipants than drop-off. The personnel whocollect materials must be trained in handlinghazardous waste, including how to pack andseparate the waste in the collection vehicle.It also allows participation by housebound

individuals and others who cannot travel toa collection site. Sometimes the programs

14

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

18/78

S E L E C T I N G

are offered to certain individuals in additionto the one-day event.

Curbside Col lect ion

Curbside programs usually are limited toa few selected wastes collected from house-holds on a regularly scheduled basis. Restric-tions on the types of waste are necessary

C O L L E C T I O N M E T H O D S

because leaving highly toxic or incompat-ible wastes at the curb can be dangerous,

and because collecting and transportinga variety of hazardous materials in residen-tial neighborhoods presents logisticaldifficulties.

The most common type of waste

collected at curbside is used oil. More than115 communities have set up programs to

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

19/78

S E L E C T I N G C O L L E C T I O N M E T H O D S

collect recyclable used oil at curbside. Othercommunities collect household batteries andpaint at curbside.

Point of Purchase

In some commun i t i es , a few types ofHHW can be returned to retail stores.community HHW program planners can

publicize these point-of-purchase programsas part of an overall HHW managementstrategy.

Retailers have implemented some point-

of-purchase programs voluntarily. in NewHampshire andVermont for example, somehardware and jewelry stores collect custom-

ers spent household batteries in buckets orspecially designed cardboard boxes.

In addition, several states require that cer-tain retailers take back some types of HHW.In Massachusetts and New York, for exam-ple, retailers must take back automobile bat-teries and used motor oil. Regulations inConnecticut, Minnesota, and Oregon bancar batteries and used oil from landfillsand/or require deposits and retailer redemp-tion.

Regulations regarding proofs of pur-

chase, deposits, and surcharges for returnsare different in each state. Massachusettsused oil law, for example, requires proof ofpurchase. Auto battery regulations usuallyrequire retailers to post a notice informingcustomers that they may return their batter-

ies and stating how many may be returned atone time.

16

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

20/78

Se ecting Waste

anagement

Methods

17

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

21/78

S E L E C T I N G M A N A G E M E N T M E T H O D S

n designing a collection program, it is important to determine what will happen to thewastes that are collected. When selecting among various waste management options,

HHW program planners should try to recycle or offer for use as much of the collectedwastes as possible. The HHW that cannot be recycled or used should be managed as a hazardo-us waste. If the communities use contractor services to manage some or all of this HHW,waste management priorities and procedures should be communicated clearly to the hazard-

ous waste contractor.

In addition, it is essential that the pro-gram planners investigate the soundness ofany facility where the waste will end up-particularly if CESQG waste is accepted(see Appendix A). The planners should askpotential contractors about the methods theywill use to manage the wastes, and theyshould also ask for copies of the permits for

the hazardous waste facilities that are to beused. Planners can also contact the state haz-ardous waste agency (see Appendix B) tofind out if a facility is properly permitted.

Reduce through Use

Reusing materials brought to HHW col-lections can reduce the amount of HHW thatthe contractor must manage, often signifi-cantly lowering program costs. Some com-munities have set up waste exchanges tomake materials available for other partici-pants use. These exchanges can take placeat a HHW drop-off site or through

telephone/hotline referrals. For example,reusable paint can be placed on drop-and-swap tables for collection program partici-pants to pick up, or it can be bulked andblended for use by people or institutionswho request the paint. This second-hand

paint is readily accepted by the public, com-munity groups, religious and recreationalcenters, graffiti removal programs, and

1Duxbury, Dana and Phi l ip Mor ley. 1990. Overview of

collection&management methods. Proc. of the Fifth

National Conference on Household Hazardous waste

Managements, November 5-7, 1990, San Francisco,

California, pp. 251-274.

schools. Experience shows that paintexchanges can reduce the amount of paintbeing disposed of at HHW collections by asmuch as 90 percent.

1

EPA recently prohibited mercury in indoor latex paint. Latex paintexchange programs and disposal, however, still must be carefully

managed.

Interior latex paint manufactured before August 20,1990, might

contain mercury. For this reason, all latex paint in a paint exchange or

drop-and-swap program should be assumed to contain mercury

and labeled FOR EXTERIOR USE ONLY. Using interior paint

outside will substantially reduce the risk from exposure to mercury.

Interior paint used outside, however, might not hold up as well as

paint originally manufactured for exterior use. Alternatively, interior

latex paint may be swapped for interior use if mercury levels of less

than 200 parts per million (ppm) can be confirmed. This can be done

in several ways

A commercial laboratory can test the paint for mercury.

The National Pesticides Telecommunications Network

(800-858-7378) provides names of paint brands that contain less

than 200 ppm of mercury.

The date of manufacture might appear on the label; no interior

latex paint manufactured after August 20, 1990, contains

mercury. No paint manufactured after September 30, 1991, may

contain mercury.

Usable latex paint can be consolidated and then might or might

not be reprocessed. The consolidated paint should be tested for

mercury. If it contains more than 200 ppm, it must be labeled FOR

EXTERIOR USE ONLY.

Unusable latex paint (such as paint that is frozen or solidfied) that

contains more than 200 ppm of mercury should be managed as

hazardous waste.

18

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

22/78

S E L E C T I N G M A N A G E M E N T M E T H O D S

Other materials suitable for reuse caninclude unwanted pesticides, cleaning prod-ucts, and automotive products. These materi-als often can be used by the sponsoringmunicipality for its buildings and vehicles.

Communities should offer products only ifthey are in the original container and the la-bel is intact and legible. They should not of-fer products if the container is banned,leaking, rusting, or otherwise damaged.Products should not be repackaged for reuse.

R e c y c l i n gA significant percentage of HHW can be

recycled. For example, used oil can be

rerefined for use as a lubricant. It also canbe reprocessed for burning as a supplemen-tal fuel (as can oil-based paint and ignitableliquids). EPA has issued several publicationsto help communities safely collect and recy-cle used oil (see Appendix C, ProjectROSE).

Other recyclable HHW includes:

Antifreeze.

Latex paint. (Up to 50 percent of latex

paint can be recycled by filtering, bulk-ing, and blending it for reuse.)Lead acid batteries. Lead used in dentalx-rays.Mercury-oxide, mercury-silver, silver-oxide, and nickel-cadmium householdbatteries. Several firms in the UnitedStates take these batteries for a fee; thecontractor can be required in the con-tract to investigate the option of ship-ping used batteries to one of these firms

for recycling.Fluorescent light bulbs.

Some communities sponsor recyclables-only days to divert the large-volume materi-als (motor oil, car batteries, and latex paint)from HHW collections and to reduce the

amount of waste that the contractor has to re-ceive, package, and process. Recycling days

save money because they often are staffedby the sponsor. Communities that sendHHW off site for recycling should contacttheir state environmental regulatory agen-cies to identify recyclers and to verify that

the recycler is reputable (see Appendix Bfor a list of state regulatory agencies).

The results of the State of FloridasAmnesty Days show the great potentialfor recycling HHW received at one-day

R e c y c l i n g U s e d O i l :

ject ROSE

For over 14 years, a trailblazing

program in Alabama has worked to

stimulate the collection of used

automobile oil for recycling. Project ROSE

(Recycled Oil Saves Energy) has taken the

lead in helping communities across the

state develop used oil recycling programs

tailored to local circumstances.

Project ROSE has built an extensive

infrastructure for recycling used

automobile oil generated by people whochange their own oil (do-it-yourselfers)

throughout Alabama. Because much of

Alabama is rural, collection centers, in

the form of service stations, are the most

widely used system. In addition, several

larger cities provide curbside collection of

used oil.

The program uses publicity and

education to develop the momentum to

start local used oil recycling programs and

then coordinates the effort of

established networks by matching buyers

of used oil with collectors. This strategy

relies heavily on recruiting leaders from

local organizations, who then work with

Project ROSE to help introduce and

support recycling programs in their area.

19

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

23/78

S E L E C T I N G M A N A G E M E N T M E T H O D S

collections. Thirty-six percent of the HHWcollected at 107 Amnesty Days (984,655pounds out of a total of 2.7 million pounds)was recycled over a two-year period. The re-

cycled material consisted of used oil, car bat-

teries, and latex paint.

Trea tmen t

Treatment technologies reduce the vol-ume and/or toxicity of HHW after it is gener-ated. These technologies include chemical,physical, biological, and thermal treatment.

Common treatment procedures are neutrali-zation of acids and bases, distillation of sol-vents, and incineration. The methods are

dictated by the types of waste, proximity totreatment facilities, cost, and the contrac-tors access to treatment facilities. However,

the contract can specify the waste manage-ment methods to be used. If the waste is sent

off site for treatment, the contractor should

provide the sponsor with documentationverifying the wastes final destination.

Landf i l l

As a result of current and pending banson land disposal of certain hazardous wastesand the efforts of communities to reduce theamount of HHW sent to municipal solidwaste landfills, more HHW is being reused,recycled or treated. As with waste destinedfor offsite treatment the hazardous waste

hauler should provide the sponsor with

manifests, state-approved shipping docu-ments, or similar documentation verifying

the wastes final destination and showingthat the hazardous waste landfill is properly

permitted.

Procedures forExc luded Wastes

HHW program planners and contractorsoften exclude certain wastes from collection

programs. Frequently excluded wastes in-clue radioactive materials, explosives,

banned pesticides, and compressed gascylinders. Program organizers must let par-

ticipants know which wastes will not be ac-cepted and must give them other optionsand instructions for managing the excludedwastes. For example, the police usually willarrange for pickup of explosives. Smoke de-tectors, which often contain a minute quan-

tity of radioactive material, are accepted by

some manufacturers (see product labelingfor instructions). If participants are not pro-vided with alternative management options,

they often discard these wastes in the near-

est trash can.

Information is available through EPA-sponsored environmental

outreach programs

Informational materials on recycling reuse, disposal, andcollection program design are available through: RCRA

Hotline 800424-9346; the Waste Watch Center

508470-3044 and the Solid Waste Information

Clearinghouse 800-67SWICH.

With EPA support the International City Managers

Association (202-962-3672) and the Solid Waste Association

of North America (301-585-2898) provide technicalassistance to communities and other nonprofit groupsthrough a peer matching program. This program provides

direct, hands advice and assistance on a peer-to-peerbasis (e.g., mayor-to-mayor).

20

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

24/78

Minimizing Liability

21

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

25/78

M I N I M I Z I N G L I A B I L I T Y

Communities can be liable for an injury to a collection day worker, an accidental re-lease of HHW to the environment at the site, or an accident during the transportationof HHW from the collection site to the disposal site. The following recommendations

can help communities minimize potential liability.

Becom e Fami l iarWith Nat ional ,St ate, and LocalHazardous Wast eRegulations

Planners of community HHW

programs must know the laws that governtheir collection activities. Planners also

should be aware that their state might have

requirements that are more stringent thanthose set by the federal government.

In addition, program planners should be

familiar with regulations governing manage-ment of specific wastes. For example, con-

solidated oil-based paint must be tested for

polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) before itis sent to a supplemental fuel-burning facil-ity. Paint that contains more than 50 partsper million of PCBs must be sent to an incin-

erator permitted to burn PCBs under the

22

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

26/78

M

Toxic Substance Control Act. Latex paint

usual] y is not considered a hazardous waste.Several states recommend treating it as ahazardous waste, however, because of thelevels of heavy metals found in some brandsand formulations.

While hazardous waste regulations mightseem complex at first, program plannersshould remember that there is potential li-ability associated with taking no action at allto manage HHW. By complying with the re-quirements set out in federal, state, and locallaws, communities can reduce their overallliability. Appendix A summarizes the federalrequirements that apply to HHW programs.

Develop a Safe ty P lan

Well in advance of collection day, the

sponsor (or contractor) should develop asafety, accident prevention, and contingencyplan. Hazardous waste management firms

experienced in servicing HHW collectionscan provide a sample plan. The plan shouldinclude steps for preventing spills, a contin-gency plan in the event of a spill or acci-

dent and a list of the health and safetyequipment available on site. The plan alsoshould specify when an evacuation wouldbe necessary, the evacuation routes andmethods, and who would be in charge of an

evacuation. For example, primary emer-gency authority should be designated to aspecific police and fire department if morethan one department has jurisdiction. Policeand fire departments should be involved inthe planning and provided with the layout of

the collection site, information about thewastes that will be handled, and possibleevacuation routes.

A copy of the safety plan should be avail-able at the collection program. One personshould be designated to control any emerg-

ency operation.

I N I M I Z I N G L I A B I L I T Y

Make Training andPubl ic Educat ion aHigh Pr ior i t y

Proper training of the sponsors in-house

staff and volunteers is essential for minimiz-ing potential problems on collection day.Section 8 discusses training requirements ingreater detail. Public education and public-ity also can help ensure a safe operation.Publicity should inform participants abouthow to safely package their HHW and trans-

port it to the collection site. For example,participants should be instructed not to trans-port HHW within the passenger compartm-

ents of their vehicles.

Obta in t heNecessary Insurance

The sponsor should ensure that theprogram has adequate insurance to covergeneral, employee, transportation, and envi-ronmental liability, Some communities willchoose to self-insure for any HHW collec-tion liability, especially when a contractorhas most of the responsibility. The minimuminsurance required includes:

General Liability Insuran ce. Contrac-tors managing all collection site opera-tions and activities usually provide $1

million to $2 million of general liabilityinsurance for damage to property or for

bodily harm at the collection site causedby actions of the contractors staff. Thiscoverage does not apply to propertydamage or bodily harm caused by the

sponsors staff or volunteers.Motor Vehicle Insurance The contrac-

tor needs insurance to coverall drivers

and vehicles transporting the collectedwaste.In-Transit Insurance. In-transit insur-

ance is required by the Department ofTransportation for interstate movement

23

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

27/78

M I N I M I Z I N G L I A B I L I T Y

of hazardous materials or waste. Thecontractors coverage, up to $5 million,

will vary according to the types of mate-rials transported. This insurance covers

environmental restoration of property orcompensation for bodly harm.

s Indemnification Clause. The contract

with the hazardous waste firm should in-clude an indemnification clause stating

that the sponsor is blameless in the

event of contractor negligence, acts ofomission or wrongdoing. Similarly, thecontractor can request indemnificationby the sponsor for any costs incurred by

the sponsors negligence.s Workers Compensation Insura nce

The sponsor should obtain coverage for

any staff or volunteers working at thecollection day who are not provided by

the contractor.

The sponsor also can require additionalprotection from the contractor to help mini-

mize liability, including:

A bid bond to cover the sponsor fortime and expenses for the bid period in

the event that a contractor turns downthe contract after it is awarded.A performance bond to ensure satis-factory performance and, if necessary,

cover the costs of completing the pro- ject according to the contract.A certificate of insurance from

the contractors insurance company,

and a clause in the contract requiring

that the sponsor be given notice in theevent of cancellation of the contractorspolicy.

In addition, the sponsor should ask to see

a copy of the TSDFs environmental impair-ment liability insurance. These facilitiesneed this insurance to cover lialility under

the Resource Conservation and RecoveryAct (RCRA), the federal law covering haz-ardous waste management. The insurance is

not available to HHW collection programs.

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

28/78

F U N D I N G T H E P R O G R A M

Anticipating and reducing costs of a HHW program, as well as locating funding

sources, are major concerns for program planners. However, many communitieshave found creative ways to finance their programs and effective ways to cut costs.

HHW program costs generally increaseas the amount of waste collected increases.

It is important to keep in mind, however,that the potential consequences of mismana-ged HHW-soil and ground-water contami-nation, hazardous emissions at landfills,

worker injury and equipment damage, inter-rupted water treatment, and contaminated ef-fluent at water treatment plants-can result

in much greater costs.

Fact ors that Af fec tc os t s

A review of the data on approximately

3,000 collection programs held since 1980

indicates that costs for a one-day HHW

collection range from as little as $10,000

to more than $100,000. The final cost of aHHW collection is difficult to predict be-

cause many variables cannot be estimatedor controlled easily. These variables in-

clude the number of households that par-

ticipate, the types and amount of waste

collected, and the waste management

methods used. Major urban multi-site

collection events, targeted farm pesticide

collections, and collections in communi-

ties located a long distance from hazard-

ous waste disposal facilities willexperience higher costs. See box for devel-

oping a rough cost estimate for a one-day

HHW collection. This formula is based on1991 estimates of disposal costs. These

estimates might need to be adjusted ifwaste management costs change. This

formula is based on much of the work be-

ing done by a contractor. Programs that

use less contractor help and that rely more

on recycling and reuse for waste manage-ment will greatly reduce the cost.

Part ic ipat ion

On average, each participant brings 50 to100 pounds of HHW to a collection, at a

cost to the sponsor ranging from $50 toslightly more than $100 per participant.Participation rates usually range from one tothree percent of eligible households and canbe as high as 10 percent. Suburban commu-nities, especially those with a hazardous

waste problem or a solid or hazardous wastefacility, experience high rates of participa-

tion. Extensive education or publicity pro-grams also can increase participation rates.

Wast e Managem entMethods

Waste management costs are the largestitem in the HHW program budget. The over-

all waste management costs will depend onthe types of waste collected and the wastemanagement methods that are used. For ex-ample, programs that accept only recyclable

materials or provide a drop-and-swap areawill experience much lower waste manage-ment costs and lower personnel costs aswell. Reusing or recycling HHW or burning

it as a supplemental fuel is less expensivethan incinerating the waste at a hazardous

waste facility. Pesticides, especially those

containing dioxin, and solvent paints andother materials containing PCBs can be very

expensive to manage ($850 per 55-gallondrum in 1991). Burning used oil and solvent-based paint as supplemental fuel typicallycosts the sponsor $175 to $250 in manage-ment fees. In 1991, the cost of sending most

26

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

29/78

Controlling Costs

Funding

Program

the

and

25

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

30/78

F U N D I N G T H E P R O G R A M

other wastes to a hazardous waste incinerator

or land disposal facility ranged from $350 to

$500 per drum. These costs can vary andmight increase over time; the hazardous waste

contractor or appropriate state agency can pro-vide current rate schedules.

Other factors will affect waste manage-ment costs as well. For example, contractorswho own and operate their own TSDFs orhave access to facilities close to the collec-tion site might be able to charge less for acollection than other contractors. Communi-ties that are located closer to hazardouswaste management facilities also might

benefit from lower costs.

Col lect ion Methods

The programs collection method also

affects the overall cost. For example, col-lecting HHW door-to-door is more expen-

sive than holding a drop-off collectionday. Permanent programs might be morecost effective than one-day collections.The number of participants might increasewith a permanent program; however, in a

permanent program, there are often more

opportunities to arrange for recycling orreuse of collected materials, resulting in

less waste per participant to be disposed of

as hazardous waste.

Estimating Costs.

There are no proven formulas for estimating cost fora one -day HHW collection.

Below is a formula for a very rough cost estimate range:

.01 H (low participation) x $350 + $5,000=$

8 (consolidation)(low estimate)

.03H (high participation) x $350 +$5,000=$

4 (no consolidation) (high estimate)

H is the number of households in the target area.

The formula produces a range, reflecting a participation rate from one to

three percent of the targeted households.

If oil and paint are to be consolidated, divide the number of expected

participants by eight, as shown in the equation, to calculate the number of

55-gallon drums. (It generally takes seven or eight households to fill a

55-gallon drum of waste.) If no wastes are consolidated, divide by four, as

shown in the equation.

$350 is the average cost of treatment/disposal per 55-gallon drum.

Add $5,000 for set-up and personnel costs.

Local staff time, publicity, and education are additional but are usually not a major

cost item for one-day collection programs.

Note: Dollar figures above are 19% estimates.

27

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

31/78

F U N D I N G T H E P R O G R A M

Ways To Min im izeCosts

program sponsors continue to find waysto reduce both overall costs and the average

cost per participant. For example:

Consolidating instead of lab-packingHHW reduces costs by allowing formuch more waste per drum. (A lab-pack

consists of a large container that holdsseveral smaller containers.) Paint used

oil, and antifreeze are frequently

consolidated.Some programs reduce costs by usingvolunteers (only for low hazard items)or city or county personnel to receive,

consolidate, and package the waste,rather than using contractor staff forthese functions.The sale of some recyclable items, such

as silver-oxide button and lead-acid bat-teries, can help defray a programs costs.

Of course, one of the best cost-cuttingmeasures is to educate the public about howto reduce HHW generation and how to mana-ge existing HHW without bringing it to a

collection center. For example, consumers

can bring used Oil and antifreeze to some

service stations. In addition, wastewatertreatment plants in some communities takeused oil to discourage improper disposal of

this waste and prevent damage to the treat-

ment plant. Generally, car batteries can bereturned to the point of purchase.

Obt ain ing Funding

HHW management program sponsorshave obtained funding from a wide varietyof sources. They have used state, county,

and local general funds; taxes, fees, and pen-alties; in-kind contributions from industry,cities, and districts; and the help ofvolunteers.

St at e and LocalGovernments

The majority of funding for local govern-ment programs comes form municipal solidwaste budgets. In addition, county and localagencies that benefit from HHW collection

days often contribute a portion of their budg-ets to HHW management programs. Amongthe agencies that benefit from HHW collec-

tions are water and sewer departments, sinceless HHW is poured down drains; fire and

health departments, since less HHW isstored in homes; and public works &part-ments, since less HHW is discarded withmunicipal trash. Some state environmental

agencies, such as departments of natural re-sources or the environment also providefunds for HHW management programs.

Sources of state funding have included stateSuperfund budgets, oil overcharge funds,

surcharges on environmental services or haz-ardous products, and special environmentalbond issues and trust funds.

Fees and Taxes

Many communities increase landfill tip-ping fees, property taxes, or water/sewerfees to create a fund for managing HHW.

Some communities also have imposed userfees, but these might be a deterrent to partici-pation in the collection program, since

household residents in most states legallycan throw HHW in their trash.

Some states have instituted specific taxesfor HHW programs. For example, the State

of Washington has imposed a tax on the firstuse of certain chemicals by manufacturersor wholesalers. The tax will be used in part,

to fired county HHW collections. Retailersin Iowa selling prducts covered under the

shelf labeling law pay a $25 registration fee.In New Hampshire, a tax on hazardous

28

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

32/78

F U N D I N G T H E P R O G R A M

waste generators funds matching grants to

communities for HHW collection programs.In Florida, local governments receive three

percent of the gross receipts from permittedwaste management facilities.

Contr ibut ions,In-Kind Donat ions,And Volunteers

Donations of money, materials, and labor

are the lifeblood of many community HHWprograms. These donations can come frommany different sources:

s

Cities counties, civic groups, environ

mental organizations, and corpora-

tions often provide seed money ormatching grants for collections.Hazardous waste contractors some-

times donate collection and transporta-tion services.Local industries or businesses that pro

duce or distribute household productsthat can become HHW sometimes con-tribute money or services to HHW man-agement programs because theyrecognize the importance of product

stewardship. In some communities, lo-cal printers have donated services for advertising or education materials.

In late 1986, the Seattle Metrocenter Young Mens Christian Association (YMCA)

(see Appendix C for address), the community development branch of the Greater

Seattle YMCA launched an impressive campaign to sponsor and fund a HHW

collection day in King County, Washington.

Metrocenter decided to seek the help of outside catalysts to develop a HHW

collection program. Ultimately 15 cities, King County, and several other public

authorities and agencies joined together to sponsor a series of major HHW

roundups between 1987 and 1989.

Fourteen different local and regional government agencies provided funding for the

roundups. Additional financial support was provided by:

. A cigarette tax.

. Revenue from a Department of Ecology tax on hazardous materials sold within

the state.

. A water quality fund, a county solid waste fund, and the general funds of cities.

. In-kind contributions from cities, districts, and corporations.

Metacenter also made extensive use of volunteers to stretch its resources for the

roundups. For example, chemistry graduate students performed some of the

actual site work.

29

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

33/78

State and municipal agency staff and

F U N D I N G T H E P R O G R A M

s Civic and environmental organizations

can provide volunteers to help plan, publi-

cize, or staff the HHW collection. Volun-

teers can be used to direct traffic, hand outliterature, fill out questionnaires, and han-

dle nonhazardous waste.

local fire and police departments often

provide supervision and traffic control.

Programs can attract direct financial

contributions, in-kind donations, and vol-

unteer services by giving donors positiverecognition, such as a mention in flyers,

an award, or a recognition ceremony. Apublicly acknowledged donation from one

group or company often encourages othersto contribute or participate in some other

way.

30

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

34/78

Publishing the

Request for

Proposals andSigning the Contract

313 5 7 - 4 4 5 0 - 9 3 - 3 : Q L 3

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

35/78

R F P s A N D C O N T R A C T S

If a contractor is to be used to do some or all of the collection work, the HHW collectionprogram probably will issue a Request for Proposal (RFP). An RFP will solicit informa-

tion on which contractors are available and qualified to manage a HHW collection pro-

gram, and the amount they will charge. Most local governments have specific procedures forissuing RFPs. A contractor should be selected based on the proposals received in response tothe RFP, and a formal contract between the sponsor and contractor must be signed. This proc-

ess ensures that the community is provided with all the necessary services at a reasonablecost, and that the roles of everyone involved in the collection event are clearly defined. This isthe only way to ensure proper management of the waste.

Issue t he RFP

A good RFP provides a comprehensive

description of the services to be provided sothat prospective contractors can bid on thecost of delivering those services. The more

specific and clear the RFP, the better the

chances of obtaining complete proposalsand realistic bids.

An RFP can include the followinginformation:

A detailed narrative description of thesponsors goals for the program.The proposed collection site(s) anddate(s).The size of the targeted population and

types of generators (e.g., households,

farmers, and/or schools).The size and relevant characteristics,

such as community demographics, ofthe targeted geographic area.The percentage of the targeted popula-tion within five miles of the selected site.Copies of the completed manifests.The extent and focus of planned educa-tion and publicity (to help estimate par-ticipation rates).The targeted waste categories.

The type of collection (drop-off, curb-side, etc.)Any specific waste handling require-ments.

Use of volunteers and in-house staff andthe tasks they will perform.Training required for HHW handlers.All services required of the contractor,potentially including:

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

unloading HHW from participantsvehicles (for a drop-off collection).

pre-screening waste.

sorting, segregating, and packagingwaste.

testing unknown wastes.

labeling wastes.

combining materials for reuse (e.g.,paint consolidation).

filling out hazardous waste forms(manifests).

obtaining a temporary EPA identifica-tion number, if necessary (see Appen-dix A).

controlling traffic.

hauling and disposing of the waste.

Post-collection reports to be submitted.The materials and equipment to be pro-vided by the contractor (see box).The waste management preferences ofthe sponsor, including the wastes thatthe sponsor wants recycled.The ultimate destination for each waste(when the sponsor has preferences).Proof of insurance.

An escape clause to ensure that thesponsor reserves the right to reject allbids or to modify the plan.costs.

The RFP can be advertised in the local

press (this might be required by localordinance) and in waste management trade

journals. It also can be sent to the contrac-tors on bid lists (lists of qualified

32

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

36/78

R F P s A N D C O N T R A C T S

contractors are available from state, local,and EPA regional offices).

Select the Contractor

The program sponsor should base the se-

lection of the contractor on the following in-formation requested in the RFP and suppliedin the proposal:

s Contractors license. The contractormust be licensed to handle hazardous

waste in the state where the HHW col-lection will be held.

s Contractors HHW experience and

references. The proposal should includea narrative section describing the

contractors qualifications and experi-ence. It also should include a list of ref-erences from any previous HHWcollection programs handled by the con-tractor. (The sponsor should carefullycheck these references.)

Equipment

The equipment needed at the

collection day is supplied by either the

contractor or the collection program

sponsor. It usually includes:

Waste management/disposal

equipment : Awning or tent (if

needed for shelter), drums,

absorbent for spills, shipping

manifests, labels, testing equipment,

and a dumpster.

Safety equipment: Plastic

ground covering, safety

coveralls/Tyvek suits, aprons,

goggles, splash shields, gloves,

respirators, traffic safety/refIector

vests, eye wash hoses, fire

extinguishers, first-aid kits, towels,

blankets, washtubs for scrubbingcontaminated clothing, and air

monitoring instruments

(recommended for monitoring

explosive vapor and organic vapor

levels).

Traffic control equipment:

Traffic cones, barriers, and signs.

Furniture: Tables, benches,

stools, and chairs.

Other equipment: Portablebathroom (if needed), portable

water (if needed), food, dollies,

dumpster for garbage, stapler, tape,

markers, scissors, hammers,

clipboards, coolers with ice, coffee

maker, shovels, brooms, and

garbage bags.

33

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

37/78

R F P s A N D C O N T R A C T S

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

Compliance record. (State and environ-

mental regulatory agencies also can pro-vide the regulatory compliance/violationrecords of contractors.)Insurance/indemnification providedby the contractor. A list of insurance

carriers and policy numbers should beincluded.Waste management services offered

and the immediate and ultimate desti-

nation of the collected waste. A con-

tractor might own waste managementfacilities or might contract inde-pendently with incinerators, landfills,treatment facilities, and recycling firms.The sponsor should confirm the relation-ship of the contractor with any treat-

ment and/or disposal facilities to beused. The sponsor also should receivecopies of manifests or other shippingdocuments confirming the receipt of thewastes at the facilities identified by the

contractor.Contractor costs. The proposal should

include itemized costs for site set-up, la-bor, equipment materials, hazardous

waste training, transportation, and

disposal.

Available collection dates. Fall andspring weekends are especially busy.The contractor should have enoughequipment and personnel to operate atthe times the sponsor selects.A list of wastes not accepted by the

contractor. If a community expects

large quantities of unusual wastes, this

might be a consideration in choosing thecontractor.A list of wastes that will be consoli-

dated and those that will be lab-

packed in original containers.

Consolidation of high-volume wastescan result in significantly reduced coststo the sponsor.A sample Contract The contractor usu-

ally provides a sample contract with the

proposal. (If the RFP contains a modelcontract, the contractor can accept it ormodify it as necessary.)How recyclable materials, such as

used oil, batteries, paint and anti-

freeze, will be ma naged. Th is should

specify any offsite recycling facilitiesthat will process these materials.The number and level of training ofpersonnel proposed for the collection.

Highly trained personnel are more ex-pensive and are not always needed. (Forexample, they might not be necessary ata recyclables-only event or a paint drop-and-swap.)A health and safety plan. The proposal

should include a safety, accident preven-

tion, and contingency plan. (The spon-sor also might need to be involved inensuring the availability and coordina-tion of emergency services.)Cost per drum, per product, or per

unit of waste. It also must be clear howmuch waste will be placed in each drum

or container.

Wri te the Contract

Once a contractor is selected, the sponsorand contractor sign a formal contract agree-ing to the services the contractor will pro-vide and the compensation the contractorwill receive. The contract usually is based

on the contract in the original RFP or theone supplied in the proposal. It usually is alengthy document, containing addenda withcopies of insurance policies and rate and per-sonnel schedules. It should include the fol-lowing clauses:

s The names and addresses of all the par-ties to the contract.

The specific role and status of each

party, and the terms and conditions un-

der which each operates.A full description of the services to be

performed.

34

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

38/78

R F P s A N D C O N T R A C T S

The time, place, and duration of the swork.The fee schedules for all thework to be s

done.

Submission of proof (manifests) of de-livery of all wastes prior to payment to

the contractor.The default guarantees and assurance

Any insurance and liability guarantees

and requirements.The procedure for amending provisionsof the contract.The contractors guarantee of compli-ance with any applicable laws.

and bond provisions for the qualityand completeness of the work to beperformed.

35

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

39/78

R F P s A N D C O N T R A C T S

s The data the contractor will provide to

assist in evaluating the program.s A savings clause that protects the re-

mainder of the contract should any part

of it be deemed illegal or inappropriate.

As with the RFP, the more specific, com-plete, and clear a contract is, the less the con-tractor will have to assume and the moresatisfactory the results will be. State hazard-ous waste contacts (see Appendix B) usually

have current model contracts that cover allfederal and state requirements. The indemni-fication and insurance clauses usually causethe most difficulty. The contract should indi-cate clearly which liabilities and hazards arecovered and to whom the indemnificationand insurance clauses apply (e.g., contrac-tors, haulers, municipality and individualdepartments, or volunteers). The sponsorslegal advisors should review the contractbefore it is signed.

36

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

40/78

Selecting, Designing,

and Operating the

Collection Site

37

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

41/78

S I T E C O N S I D E R A T I O N S

Proper site selection, design, and operation are crucial in promoting maximum participa-tion in the HHW collection and subsequent collections. An easily accessible, effi-ciently run site will help ensure positive experiences on collection day, which can

result in favorable publicity for the next event.

Site Select ion

The site chosen for the collectionshould be well known, centrally located,and easily accessible. It also should be

well removed from residences, parkswhere children play, and environmentally

sensitive areas, such as open bodies ofwater, wells, faults, and wetlands. Localzoning regulations might specify required

setbacks and buffer zones and might iden-

tify acceptable or restricted areas. Using

sites with an impermeable surface (e.g.,

pavement or concrete) helps to minimize

environmental risks. Onsite utilities shouldinclude running water, fire hydrants, and

electric hookups (or generators) in caselights are needed to pack and label the

HHW after dark.

Collection sites typically are located onpublicly owned land, such as stadium park-ing lots, solid waste landfills or transfer sta-tions, schools, fire stations, and publicworks yards. A wastewater treatment plantis a good collection site because it alsooffers the opportunity to educate the public

about water pollution problems caused byimproperly managed HHW.

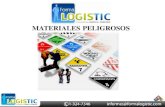

Simple site plan for a one-day drop-off HHW collection program.

38

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

42/78

Shower Rest Rooms Safety Gear Check-Out Fork LiftBreak Area Kitchen

Dumpster

Waste Management Company's Semi Truck

Decontamination Area Safety Station

Recycling Area

Flammables Explosive Poisons Aerosols Corrosives

Unloading Zone for Paint

Paint Receiving

Fire Truck or Aid Van

"ESCAPE ROUTEEXIT

ENTRANCE CHECK IDENTIFICATION TRAFFIC FLOW & TRAFFIC HOLDING LINE

Legend (not to scale): DRUM TABLE PALLET

S I T E C O N S I D E R A T I O N S

The simple plan shown in Figure 1 mightnot be adequate for all programs, however.

Depending on the design and goals of theprogram, a more complex layout might be

required, such as the layout shown in Figure2. Described below is a commonly used sys-

tem for designing the site layout. There aremany other ways an effficient collection can

Sit e Design andOperat ion

A well-designed and well-operated HHWcollection site allows participants to movethrough the collection area quickly and effi-

ciently. It includes areas for people who re-quire special attention, and adequate spacefor waiting lines. It also has staff on hand todirect traffic, offer informational materials,and answer questions.

The size of the site is critical to the effi-ciency of the program; sponsors should planfor traffic overflow. The site should beatleast 10,000 square feet.

Figure 1 shows one example of a site plan

for a one-day drop-off collection program.

be achieved.

Entrance

Collection staff or volunteers shouldstand at the entrance or check-in station togreet the participants and direct them to thereceiving area. Police officers or volunteer

personnel should be stationed just outside

Drum storage

I

Unloading Zone forNon-Hazardous

Wastes Unloadfor Paint

for Ineligible Vehicles Unloading Zone

I

Pallet

More complex site plan for a one-day drop-off HHW collection program.

39

-

8/3/2019 GUIA Epa Gestao Matpel Domiciliares

43/78

S I T E C O N S I D E R A T I O N S

the entrance to manage traffic flow that can-not be contained on the site.

Several unloading lanes with signs and

traffic cones can help control the flow of

traffic on and off the site. Separate expresslanes for the wastes received in the highest

volume (usually paint and used oil) can helpspeed up service to participants.

Before participants drop off their HHW,they can be asked to document their eligibil-ity to participate in the collection (resi-dency), complete questionnaires, and list thewastes they have brought to the site. (A sam-ple questionnaire is provided in Appendix

D.) The staff can offer informational materi-als, answer questions, and provide informa-tion about what to do with excluded wastes.

To minimize traffic delays, these tasks canbe completed while participants wait to en-ter the receiving area.

Receiving Area

At the receiving areas, trained personnel

(usually the contractors staff) screen eachvehicle for unknown, unacceptable, recycla-ble, or nonhazardous waste. Participantsshould not be permitted to remove any

wastes from their own cars and should be en-couraged to remain in their cars. The staffmembers unload recyclable materials andtake them to the recycling area. The recy-clable should be handled and packaged ac-

cording to any instructions from therecycling firm. They then take the rest of the

acceptable wastes to a sorting table. After re-moving the HHW from the vehicle, the staff

members direct the participant to the exit.

Sort ing AreaIn the sorting area, staff members or con-

tractor personnel sort the wastes into hazardcategories and deliver them to the packingarea. They place empty containers and non-hazardous waste in dumpsters located in the