Chinaman (Porcelain)

description

Transcript of Chinaman (Porcelain)

-

Chinaman (porcelain)

This business card from about 1764 reads, William Hussey,China and Glass Man, In Coventry Street, Piccadilly, London.Sells all Sorts of China, Glass and Stone Ware; Likewise JapanDressing Boxes for Ladies Toilets with Variety of India Fans &c.&c. Wholesale and Retail. N.B. The above Goods for Exporta-tion. It is embellished with Chinese motifs such as a gure witha pigtail.[1]

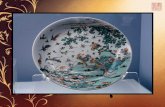

Blue and white porcelain in a Chinese style. The willow patternwas actually invented in England and this piece was produced inStaordshire.

William BELOE, China-Man,Market-Place, Norwich

Has just received from the India Companys Sale a largeand regular Assortment of useful and ornamental China,

Japanned Tea Boards, Waiters, Toilet and Card Boxes,the best India Soy, Fish and Counters, Fans, etc, etc.which will be sold at the present London Prices. Hehas also a large Parcel of useful China from CommodoreJOHNSTONE's Prize Goods taken from the Dutch,which will be sold cheap.He is lately returned from Staordshire with a very largeand elegant Assortment of that much improvedManufac-tory, particularly some compleat Table Services, after theDresden Manner and from their Patterns; and in conse-quence of his frequent Attendance on that Manufactory,he will be able to supply his Warehouse in Norwich im-mediately with every new and improved Pattern.The above Goods, with all Sorts of Glass, Stone, Delft,and Earthen Ware, will be sold Wholesale and Retailupon very low Terms.N.B. All Wholesale Dealers will meet with very great En-couragement for ready Money.Norfolk Chronicle (July 12th 1783) in the British Library

A chinaman is a dealer in porcelain and chinaware, es-pecially in 18th-century London, where this was a recog-nised trade; a toyman dealt additionally in fashion-able tries, such as snuboxes.[2] Chinamen bought largequantities of china imported by the East India Company,who held auctions twice a year in London. The tradersthen distributed chinaware throughout England.Imports from China declined at the end of the 18th cen-tury. Domestic production by the English potteries be-came large and the manufacturers, such as Mason andWedgwood, became successful and supplied their own re-tail businesses.

1 Chinaware

Chinese porcelain was imported into England from the1680s. London was the main port where between oneand two million pieces were landed each year. Thesewere sold at auction by the East India Company andthe resulting trade made London the hub for distribu-tion of chinaware throughout the country. London re-mained the centre of the trade even after large scale pro-duction started in the English provinces, especially theStaordshire Potteries. This was because of the continu-ing import/export business and the concentration of artis-tic talent and the cream of society there.[3]

1

-

2 5 REFERENCES

2 Trade

The occupation of chinaman was documented by A Gen-eral Description of All Trades in 1747: This businessis altogether shopkeeping, and some of them carry ona very considerable Trade... The cost of becoming anapprentice was usually 20 to 50 but could be as muchas 200. A journeyman was given wages of 20 to 30 ayear plus board.[4] The value of the stock in trade wouldtypically be 500 but a prosperous merchant might havestock valued at 2,000 or more.One prominent chinaman of this well-to-do sort wasJames Giles who had premises in Soho and a fashionableshowroom near Charing Cross.[5][6] In the 1760s, JosiahWedgwood was the rst of the English potters to openhis own showroom in West End of London rather thanmaking bulk sales to the trade (as well as commissions forlarge services); eventually others followed. The retail sideof Wedgwoods operation was run by his partner thecultivated merchant, Thomas Bentley. Bentley opened ashowroomon the corner of St. Martins Lane, thenmovedto Greek Street in Soho and opened further showrooms inother fashionable places such as Bath.[7]

3 Competition

In 1785, they formed a trade association called the ChinaClub.[8] Collusion developed at the biannual auctions ofthe East India Company from about 1779.[9] This auctionring depressed the prices obtained at auction and so thetrade became unprotable.[10] The import duty on tea wasreduced from 119% to 12.5% in 1784. This increased thedemand for tea and so it became the preferred cargo.[11]In 1791, the Court of Directors ordered that, henceforth,china was only be carried as ballast on their vessels. Thisreduced the import trade considerably and so, in 1795,the chinaman Miles Mason of Fenchurch Street, askedwhether the company would carry private shipments ofchina for a carriage fee. They declined and Mason wenton to develop a business in Liverpool and then Staord-shire.Mason wanted to develop a method of making replace-ment pieces for existing sets of china. His experimentsled to the development of a type of pottery which, likeChinese porcelain, was strong and so resisted chipping.This was ironstone china which developed into a substan-tial business under his son, Charles, who patented the pro-cess. Many other potteries in England copied this styleand large quantities were exported to other countries suchas France and the United States.[12][9] The original tradein imports from China ceased in 1798 as the East IndiaCompany stopped making bulk sales.[10]

4 See also Worshipful Company of Glass Sellers

5 References

5.1 Citations[1] Trade Card, Victoria and Albert Museum, 2 April 2013

[2] Horace Walpole, who took the lease on Strawberry Hillfrom the toy-woman Mrs Chevenix, said of the little villain a letter to Sir Horace Mann (5 June 1747), This littlerural bijouwas Mrs Chevenixs, the toy-woman la mode,who in every dry season is to furnish me with the best rain-water from Paris, and now and then some Dresden-chinacows...

[3] Weatherill 1986, p. 51.

[4] Young 1999a, p. 158.

[5] Young 1999a, p. 173.

[6] Young 1999b, p. 264.

[7] Blaszczyk 2002, p. 8.

[8] Young 1999a, p. 160.

[9] Coutts 2001, p. 153.

[10] Godden 1983, p. 115.

[11] Copeland 2008, p. 7.

[12] Godden 1996, p. foreword.

5.2 Sources Blaszczyk, Regina Lee (2002), Imagining Con-

sumers: Design and Innovation from Wedgwood toCorning, JHU Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-6914-3

Cheang, Sarah (2007), Selling China: Class, Gen-der and Orientalism at the Department Store,Journal of Design History (Oxford UniversityPress for Design History Society) 20 (1): 116,doi:10.1093/jdh/epl038

Copeland, Robert (2008), Spode, Osprey Publish-ing, ISBN 978-0-7478-0364-5

Coutts, Howard (2001), Porcelain in Eighteenth-Century Britain, The Art of Ceramics: EuropeanCeramic Design, 15001830, Yale University Press,ISBN 978-0-300-08387-3

Godden, Georey A (1983), Staordshire Porcelain,Granada

Roberts, Gaye; Godden, Georey (1996), Masons,The First Two Hundred Years, Merrell Holberton

-

5.2 Sources 3

Smith, S (1974), Norwich china dealers of themideighteenth century, Transactions of the En-glish Ceramic Circle IX: 207

Waller, T (1747), A General Description of AllTrades: Digested in Alphabetical Order

Weatherill, Lorna (1986), The Business ofMiddleman in the English Pottery Trade Be-fore 1780, Business History 28 (3): 5176,doi:10.1080/00076798600000030

Young, Hilary (1999a), English Porcelain, 174595: its makers, design, marketing and consumption,Harry N. Abrams, ISBN 978-1-85177-282-7

Young, Hilary (1999b), Manufacturing outside theCapital: The British Porcelain Factories, Their SalesNetworks and Their Artists, 17451795, Jour-nal of Design History (Oxford University Pressfor Design History Society) 12 (3): 25769,doi:10.1093/jdh/12.3.257

-

4 6 TEXT AND IMAGE SOURCES, CONTRIBUTORS, AND LICENSES

6 Text and image sources, contributors, and licenses6.1 Text

Chinaman (porcelain) Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinaman_(porcelain)?oldid=653040692 Contributors: Wetman, Piotrus,Jeodesic, Rjwilmsi, King of Hearts, Canthusus, Kanuk, Makyen, Colonel Warden, CmdrObot, Mafmafmaf, Johnbod, Getonyourfeet,Niceguyedc, Piledhigheranddeeper, NellieBly, Addbot, Yobot, Rickyrickythemagicalheronheron, Trappist the monk, Claritas, Lgfcd,Burne-Jones and Anonymous: 1

6.2 Images File:Blueandwhite2.jpg Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/3/3a/Blueandwhite2.jpg License: Cc-by-sa-3.0 Contributors:

? Original artist: ? File:Meissen_hard_porcelain_vase_1735.jpg Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Meissen_hard_

porcelain_vase_1735.jpg License: CC BY-SA 3.0 Contributors: Own work, photographed at Musee des Arts Decoratifs Original artist:World Imaging

File:Ming_plate_15th_century_Jingdezhen_kilns_Jiangxi.jpg Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f6/Ming_plate_15th_century_Jingdezhen_kilns_Jiangxi.jpg License: Public domain Contributors: Own work Original artist: PHGCOM

File:William_Hussey{}s_business_card.PNG Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/c/c9/William_Hussey%27s_business_card.PNG License: Public domain Contributors: ? Original artist: ?

6.3 Content license Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

ChinawareTradeCompetitionSee alsoReferencesCitationsSources

Text and image sources, contributors, and licensesTextImagesContent license