85--ADATranstornosAlimentares

-

Upload

joana-tavares -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of 85--ADATranstornosAlimentares

-

8/11/2019 85--ADATranstornosAlimentares

1/10810/ July 2001 Volume 101 Number 7

...................................................................................................................................................

ADA REPORTS

Abstract

More than 5 million Americans suffer from eating disorders.Five percent of females and 1% of males have anorexianervosa, bulimia nervosa, or binge eating disorder. It is

estimated that 85% of eating disorders have their onsetduring the adolescent age period. Although Eating Disordersfall under the category of psychiatric diagnoses, there are anumber of nutritional and medical problems and issues that

require the expertise of a registered dietitian. Because ofthe complex biopsychosocial aspects of eating disorders, theoptimal assessment and ongoing management of these

conditions appears to be with an interdisciplinary teamconsisting of professionals from medical, nursing, nutri-tional, and mental health disciplines (1). Medical NutritionTherapy provided by a registered dietitian trained in the

area of eating disorders plays a significant role in thetreatment and management of eating disorders. Theregistered dietitian, however, must understand the com-

plexities of eating disorders such as comorbid illness,medical and psychological complications, and boundaryissues. The registered dietitian needs to be aware of the

specific populations at risk for eating disorders and the

special considerations when dealing with these individuals.

POSITION STATEMENTIt is the position of the American Dietetic Association

(ADA) that nutrition education and nutrition interven-tion, by a registered dietitian, is an essential component ofthe team treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa,bulimia nervosa, and eating disorders not otherwise speci-

fied (EDNOS) during assessment and treatment across thecontinuum of care.

INTRODUCTIONEating Disorders are considered to be psychiatric disorders,

but unfortunately they are remarkable for their nutrition and

medical-related problems, some of which can be life-threaten-ing. As a general rule, eating disorders are characterized by

abnormal eating patterns and cognitive distortions related tofood and weight, which in turn result in adverse effects onnutrition status, medical complications, and impaired health

status and function (2,3,4,5,6).Many authors (7,8,9) have noted that anorexia nervosa is

detectable in all social classes, suggesting that higher socio-economic status is not a major factor in the prevalence of

anorexia and bulimia nervosa. A wide range of demographics isseen in eating disorder patients. The major characteristic ofeating disorders are the disturbed body image in which ones

body is perceived as being fat (even at normal or low weight),an intense fear of weight gain and becoming fat, and a relent-less obsession to become thinner (8).

Diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa,

and eating disorders not otherwise specified (EDNOS) areidentified in the fourth edition of theDiagnostic and Statis-tical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) (10)

(See the Figure). These clinical diagnoses are based on psy-chological, behavioral, and physiological characteristics.

It is important to note that patients cannot be diagnosed with

both anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) at the

same time. Patients with EDNOS do not fall into the diagnosticcriterion for either AN or BN, but account for about 50% of thepopulation with eating disorders. If left untreated and behav-

iors continue, the diagnosis may change to BN or AN. Bingeeating disorder is currently classified within the EDNOS group-ing.

Over a lifetime, an individual may meet diagnostic criteriafor more than one of these conditions, suggesting a continuumof disordered eating. Attitudes and behaviors relating to foodand weight overlap substantially. Nevertheless, despite attitu-

dinal and behavioral similarities, distinctive patterns ofcomorbidity and risk factors have been identified for each ofthese disorders. Therefore, the nutritional and medical com-

plications and therapy can differ significantly (2,3,11).

Position of the American Dietetic Association: Nutritionintervention in the treatment of anorexia nervosa, bulimianervosa, and eating disorders not otherwise specified(EDNOS)

-

8/11/2019 85--ADATranstornosAlimentares

2/10

...................................................................................................................................................

Journal of THE AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION /811

ADA REPORTS

Because of the complex biopsychosocial aspects of eatingdisorders, the optimal assessment and ongoing management of

these conditions appear to be under the direction of an inter-disciplinary team consisting of professionals from medical,nursing, nutritional and mental health disciplines (1). Medical

Nutrition Therapy (MNT) provided by a registered dietitian

trained in the area of eating disorders is an integral componentof treatment and management of eating disorders.

COMORBID ILLNESS AND EATING DISORDERSPatients with eating disorders may suffer from other psychiat-ric disorders as well as their eating disorder, which increases

the complexity of treatment. Registered dietitians must under-stand the characteristics of these psychiatric disorders and theimpact of these disorders on the course of treatment. The

experienced dietitian knows to be in frequent contact with themental health team member in order to have an adequateunderstanding of the patients current status. Psychiatric dis-orders that are frequently seen in the eating disorder popula-

tion include mood and anxiety disorders (eg, depression,

obsessive compulsive disorder), personality disorders, andsubstance abuse disorders (12).

Abuse and trauma may precede the eating disorder in somepatients (13). The registered dietitian must consult with theprimary therapist on how to best handle the patients recall of

abuse or dissociative episodes that may occur during nutritioncounseling sessions.

ROLE OF THE TREATMENT TEAMThe care of patients with eating disorder involves expertiseand dedication of an interdisciplinary team (3,12,14). Since it

is clearly a psychiatric disorder with major medical complica-tions, psychiatric management is the foundation of treatmentand should be instituted for all patients in combination withother treatment modalities. A physician familiar with eating

disorders should perform a thorough physical exam. This mayinvolve the patients primary care provider, a physician spe-cializing in eating disorders, or the psychiatrist caring for the

patient. A dental exam should also be performed. Medicationmanagement and medical monitoring are the responsibilitiesof the physician(s) on the team. Psychotherapy is the respon-sibility of the clinician credentialed to provide psychotherapy.

This task may be given to a social worker, a psychiatric nursespecialist (advanced practice nurse), psychologist, psychia-trist, a licensed professional counselor or a masters level

counselor. In inpatient and partial hospitalization settings,nurses monitor the status of the patient and dispense medica-tions while recreation therapists and occupational therapists

assist the patient in acquiring healthy daily living and recre-

ational skills. The registered dietitian assesses the nutritionalstatus, knowledge base, motivation, and current eating andbehavioral status of the patient, develops the nutrition section

of the treatment plan, implements the treatment plan andsupports the patient in accomplishing the goals set out in thetreatment plan. Ideally, the dietitian has continuous contact

with the patient throughout the course of treatment or, if thisis not possible, refers the patient to another dietitian if thepatient is transitioning from an inpatient to an outpatientsetting.

Medical nutrition therapy and psychotherapy are two inte-gral parts of the treatment of eating disorders. The dietitianworking with eating disorder patients needs a good under-

standing of personal and professional boundaries. Unfortu-

nately, this is not often taught in traditional training programs.Understanding of boundaries refers to recognizing and appre-

ciating the specific tasks and topics that each member of theteam is responsible for covering. Specifically, the role of theregistered dietitian is to address the food and nutrition issues,

the behavior associated with those issues, and assist the medi-

cal team member with monitoring lab values, vital signs, andphysical symptoms associated with malnutrition. The psycho-

therapeutic issues are the focus of the psychotherapist ormental health team member.

Effective nutrition therapy for the patient with an eatingdisorder requires knowledge of motivational interviewing and

cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (15). The registereddietitians communication style, both verbal and nonverbal,can significantly affect the patients motivation to change.

Motivational Interviewing was developed because of the ideathat individuals motivation arises from an interpersonal pro-cess (16). CBT identifies maladaptive cognitions and involvescognitive restructuring. Erroneous beliefs and thought pat-

terns are challenged with more accurate perceptions and

interpretations regarding dieting, nutrition, and the relation-ship between starvation and physical symptoms (2,15).

The transtheoretical model of change suggests that an indi-vidual progresses through various stages of change and usescognitive and behavioral processes when attempting to change

health-related behavior (17,18). Stages include precontem-plation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance.Patients with eating disorders often progress along these

stages with frequent backsliding along the way to recovery.The role of the nutritional therapist is to help move patientsalong the continuum until they reach the maintenance stage.

MEDICAL CONSEQUENCES AND INTERVENTION INEATING DISORDERSNutritional factors and dieting behaviors may influence the

development and course of eating disorders. In the pathogen-esis of anorexia nervosa, dieting or other purposeful changes infood choices can contribute enormously to the course of the

disease because of the physiological and psychological conse-quences of starvation that perpetuate the disease and impedeprogress toward recovery (2,3,6,19,20). Higher prevalencerates among specific groups, such as athletes and patients with

diabetes mellitus (21), support the concept that increased riskoccurs with conditions in which dietary restraint or control ofbody weight assume great importance. However, only a small

proportion of individuals who diet or restrict intake develop aneating disorder. In many cases, psychological and culturalpressures must exist along with physical, emotional, and soci-

etal pressures for an individual to develop an eating disorder.

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

Medical SymptomsEssential to the diagnosis of AN is that patients weigh less than85% of that expected. There are several ways to determine 20 years of age) a BMI

-

8/11/2019 85--ADATranstornosAlimentares

3/10812/ July 2001 Volume 101 Number 7

...................................................................................................................................................

ADA REPORTS

percent of average weight-for-height can be calculated byusing CDC growth charts or the CDC body mass index charts

(23). Because children are still growing, the BMIs increasewith age in children and therefore the BMI percentiles must beused, not the actual numbers. Individuals with BMIs less than

the 10th percentile are considered underweight and BMIs less

than 5th percentile are at risk for AN (3,5-7). In all cases, thepatients body build, weight history, and stage of development

(in adolescents) should be considered.Physical symptoms can range from lanugo hair formation to

life threatening cardiac arrhythmias. Physical characteristicsinclude lanugo hair on face and trunk, brittle listless hair,

cyanosis of hands and feet, and dry skin. Cardiovascular changesinclude bradycardia (HR

-

8/11/2019 85--ADATranstornosAlimentares

4/10

...................................................................................................................................................

Journal of THE AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION /813

ADA REPORTS

limited to enable sufficient energy intake (3,45). Individual-ized guidance and a meal plan that provides a framework for

meals and snacks and food choices (but not a rigid diet) ishelpful for most patients. The registered dietitian determinesthe individual caloric needs and with the patient develops a

nutrition plan that allows the patient to meet these nutrition

needs. In the early treatment of AN, this may be done on agradual basis, increasing the caloric prescription in increments

to reach the necessary caloric intake. MNT should be targetedat helping the patient understand nutritional needs as well ashelping them begin to make wise food choices by increasingvariety in diet and by practicing appropriate food behaviors

(2). One effective counseling technique is CBT, which involveschallenging erroneous beliefs and thought patterns with moreaccurate perceptions and interpretations regarding dieting,

nutrition and the relationship between starvation and physicalsymptoms (15). In many cases, monitoring skinfolds can behelpful in determining composition of weight gain as well asbeing useful as an educational tool to show the patient the

composition of any weight gain (lean body mass vs. fat mass).

Percent body fat can be estimated from the sum of four skinfoldmeasurements (triceps, biceps, subscapular and suprailiaccrest) using the calculations of Durnin (46-47). This methodhas been validated against underwater weighing in adolescentgirls with AN (48). Bioelectrical impedance analysis has been

shown to be unreliable in patients with AN secondary tochanges in intracellular and extracellular fluid changes andchronic dehydration (49,50).

The registered dietitian will need to recommend dietarysupplements as needed to meet nutritional needs. In manycases, the registered dietitian will be the team member to

recommend physical activity levels based on medical status,psychological status, and nutritional intake. Physical activitymay need to be limited or initially eliminated with the compul-sive exerciser who has AN so that weight restoration can be

achieved. The counseling effort needs to focus on the messagethat exercise is an activity undertaken for enjoyment andfitness rather than a way to expend energy and promote weight

loss. Supervised, low weight strength training is less likely toimpede weight gain than other forms of activity and may bepsychologically helpful for patients (7). Nutrition therapymust be ongoing to allow the patient to understand his/her

nutritional needs as well as to adjust and adapt the nutritionplan to meet the patients medical and nutritional require-ments.

During the refeeding phase (especially in the early refeedingprocess), the patient needs to be monitored closely for signs ofrefeeding syndrome (51). Refeeding syndrome is character-

ized by sudden and sometimes severe hypophosphatemia,

sudden drops in potassium and magnesium, glucose intoler-ance, hypokalemia, gastrointestinal dysfunction, and cardiacarrhythmias (a prolonged QT interval is a contributing cause of

the rhythm disturbances) (27,52,53). Water retention duringrefeeding should be anticipated and discussed with the pa-tient. Guidance with food choices to promote normal bowel

function should be provided as well (2,45). A weight gain goalof 1 to 2 pounds per week for outpatient and 2 to 3 pounds forinpatients is recommended. In the beginning of therapy theregistered dietitian will need to see the patient on a frequent

basis. If the patient responds to medical, nutritional, andpsychiatric therapy, nutrition visits may be less frequent.Refeeding syndrome can be seen in both the outpatient and

inpatient settings and the patient should be monitored closely

during the early refeeding process. Because more aggressiveand rapid refeeding is initiated on the inpatient units, refeeding

syndrome is more commonly seen in these units. (2,45).

Inpatient Although many patients may respond to outpatienttherapy, others do not. Low weight is only one index of

malnutrition; weight should never be used as the only criterionfor hospital admission. Most patients with AN are knowledge-

able enough to falsify weights through such strategies asexcessive water/fluid intake. If body weight alone is used forhospital admission criteria, behaviors may result in acutehyponatremia or dangerous degrees of unrecognized weight

loss (5). All criteria for admission should be considered. Thecriteria for inpatient admission include (5,7,53):

Severe malnutrition (weight

-

8/11/2019 85--ADATranstornosAlimentares

5/10814/ July 2001 Volume 101 Number 7

...................................................................................................................................................

ADA REPORTS

utes significantly to successful long-term recovery. The overallgoal is to help the patient normalize eating patterns and learn

that behavior change must involve planning and practicingwith real food.

Partial Hospitalizations Partial hospitalizations (day treat-

ment) are increasingly utilized in an attempt to decrease thelength of some inpatient hospitalizations and also for milder

AN cases, in place of a hospitalization. Patients usually attendfor 7 to 10 hours per day, and are served two meals and 1 to 2snacks. During the day, they participate in medical and nutri-tional monitoring, nutrition counseling, and psychotherapy,

both group and individual. The patient is responsible for onemeal and any recommended snacks at home. The individualwho participates in partial hospitalization must be motivated to

participate and be able to consume an adequate nutritionalintake at home as well as follow recommendations regardingphysical activity (11).

Recovery Recovery from AN takes time. Even after the pa-

tient has recovered medically they may need ongoing psycho-logical support to sustain the change. For patients with AN, oneof their greatest fears is reaching a low healthy weight and notbeing able to stop gaining weight. In long-term follow-up theregistered dietitians role is to assist the patient in reaching an

acceptable healthy weight and to help the patient maintain thisweight over time. The registered dietitians counseling shouldfocus on helping the patient to consume an appropriate, varied

diet to maintain weight and appropriate body composition

BULIMIA NERVOSABulimia Nervosa (BN) occurs in approximately 2 to 5% of thepopulation. Most patients with BN tend to be of normal weightor moderately overweight and therefore are often undetect-able by appearance alone. The average onset of BN occurs

between mid-adolescence and the late 20s with a great diver-sity of socioeconomic status. A full syndrome of BN is rare inthe first decade of life. A biopsychosocial model seems best for

explaining the etiology of BN (55).The individual at risk for thedisorder may have a biological vulnerability to depression thatis exacerbated by a chaotic and conflicting family and socialrole expectations. Societys emphasis on thinness often helps

the person identify weight loss as the solution. Dieting thenleads to binging, and the cyclical disorder begins (56,57). Asubgroup of these patients exists where the binging proceeds

dieting. This group tends to be of a higher body weight (58).The patient with BN has an eating pattern which is typicallychaotic although rules of what should be eaten, how much and

what constitutes good and bad foods occupy the thought

process for the majority of the patients day. Although theamount of food consumed that is labeled a binge episode issubjective, the criteria for bulimia nervosa requires other

measures such as the feeling of out-of-control behavior duringthe bingeing (See Figure).

Although the diagnostic criteria for this disorder focuses on

the binge/purge behavior, much of the time the person with BNis restricting her/his diet. The dietary restriction can be thephysiological or psychological trigger to subsequent bingeeating. Also, the trauma of breaking rules by eating something

other than what was intended or more than what was intendedmay lead to self-destructive binge-eating behavior. Any sub-jective or objective sensation of stomach fullness may trigger

the person to purge. Common purging methods consist of self-

induced vomiting with or without the use of syrup of ipecac,laxative use, diuretic use, and excessive exercise. Once purged,

the patient may feel some initial relief; however, this is oftenfollowed by guilt and shame. Resuming normal eating com-monly leads to gastrointestinal complaints such as bloating,

constipation and flatulence. This physical discomfort as well as

the guilt from binging often results in a cyclical pattern as thepatient tries to get back on track by restricting once again.

Although the focus is on the food, the binge/purge behavior isoften a means for the person to regulate and manage emotionsand to medicate psychological pain (59).

Medical SymptomsIn the initial assessment, it is important to assess and evaluatefor medical conditions that may play a role in the purging

behavior. Conditions such as esophageal reflux disease (GERD)and helicobacter pylori may increase the pain and the need forthe patient to vomit. Interventions for these conditions mayhelp in reducing the vomiting and allow the treatment for BN

to be more focused. Nutritional abnormalities for patients with

BN depend on the amount of restriction during the non-bingeepisodes. It is important to note that purging behaviors do notcompletely prevent the utilization of calories from the binge;an average retention of 1200 calories occurs from binges ofvarious sizes and contents (60,61).

Muscle weakness, fatigue, cardiac arrhythmias, dehydrationand electrolyte imbalance can be caused by purging, especiallyself-induced vomiting and laxative abuse. It is common to see

hypokalemia and hypochloremic alkalosis as well as gastrointes-tinal problems involving the stomach and esophagus. Dentalerosion from self-induced vomiting can be quite serious. Al-

though laxatives are used to purge calories, they are quiteineffective. Chronic ipecac use has been shown to cause skel-etal myopathy, electrocardiographic changes and cardiomy-opathy with consequent congestive heart failure, arrhythmia

and sudden death (2).

Medical and Nutritional Management of BulimiaNervosaAs with AN, interdisciplinary team management is essential tocare. The majority of patients with BN are treated in anoutpatient or partial hospitalization setting. Indications for

inpatient hospitalization include severe disabling symptomsthat are unresponsive to outpatient treatment or additionalmedical problems such as uncontrolled vomiting, severe laxa-

tive abuse withdrawal, metabolic abnormalities or vital signchanges, suicidal ideations, or severe, concurrent substanceabuse (12).

The registered dietitians main role is to help develop an

eating plan to help normalize eating for the patient with BN.The registered dietitian assists in the medical management ofpatients through the monitoring of electrolytes, vital signs, and

weight and monitors intake and behaviors, which sometimesallows for preventive interventions before biochemical indexchange. Most patients with BN desire some amount of weight

loss at the beginning of treatment. It is not uncommon to hearpatients say that they want to get well but they also want to losethe x number of pounds that they feel is above what theyshould weigh. It is important to communicate to the patient

that it is incompatible to diet and recover from the eatingdisorder at the same time. They must understand that theprimary goal of intervention is to normalize eating patterns.

Any weight loss that is achieved would occur as a result of a

-

8/11/2019 85--ADATranstornosAlimentares

6/10

...................................................................................................................................................

Journal of THE AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION /815

ADA REPORTS

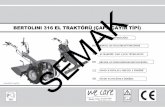

307.1 Anorexia NervosaDiagnostic criteria for 307.1 Anorexia NervosaA. Refusal to maintain body weight at or above a minimallynormal weight for age and height (eg, weight loss leading tomaintenance of body weight less than 85% of that expected;or failure to make expected weight gain during period of

growth, leading to body weight less than 85% of that ex-pected).B. Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, eventhough underweight.C. Disturbance in the way in which ones body weight orshape is experienced, undue influence of body weight orshape on self-evaluation, or denial of the seriousness of thecurrent low body weight.D. In postmenarcheal females, amenorrhea, ie, the absenceof at least three consecutive menstrual cycles. (A woman isconsidered to have amenorrhea if her periods occur onlyfollowing hormone, eg, estrogen, administration.)

Specify type:Restricting Type: during the current episode of AnorexiaNervosa, the person has not regularly engaged in binge-

eating or purging behavior (ie, self-induced vomiting or themisuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas)Binge-Eating/Purging Type: during the current episode ofAnorexia Nervosa, the person has regularly engaged in binge-eating or purging behavior (ie, self-induced vomiting or themisuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas)

307.51 Bulimia NervosaDiagnostic criteria for 307.51 Bulimia NervosaA. Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of bingeeating is characterized by both of the following:1. eating, in a discrete period of time (eg, within any 2-hour

period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than mostpeople would eat during a similar period of time and undersimilar circumstances2. a sense of lack of control over eating during the episode

(eg, a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what orhow much one is eating)B. Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behavior in order toprevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting; misuse oflaxatives, diuretics, enemas, or other medications; fasting; orexcessive exercise.C. The binge eating and inappropriate compensatorybehaviors both occur, on average, at least twice a week forthree months.D. Self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape andweight.E. The disturbance dose not occur exclusively duringepisodes of Anorexia Nervosa.

Specify type:Purging Type: during the current episode of Bulimia Nervosa,

the person has regularly engaged in self-induced vomiting orthe misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemasNonpurging Type: during the current episode of Bulimia

Nervosa, the person has used other inappropriate compensa-tory behaviors, such as fasting or excessive exercise, but hasnot regularly engaged in self-induced vomiting or the misuseof laxatives, diuretics, or enemas

307.50 Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified

The Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified category is fordisorders of eating that do not meet the criteria for anyspecific Eating Disorder. Examples include:1. For females, all of the criteria for Anorexia Nervosa are metexcept that the individual has regular menses.2. All of the criteria for Anorexia Nervosa are met except that,despite significant weight loss, the individuals current weightis in the normal range.3. All of the criteria for Bulimia Nervosa are met except thatthe binge-eating inappropriate compensatory mechanismsoccur at a frequency of less than twice a week or for aduration of less than 3 months.4. The regular use of inappropriate compensatory behaviorby an individual of normal body weight after eating smallamounts of food (eg, self-induced vomiting after the consump-tion of two cookies).

5. Repeatedly chewing and spitting out, but not swallowing,large amounts of food.6. Binge-eating disorder; recurrent episodes of binge eatingin the absence of the regular use of inappropriate compensa-tory behaviors characteristic of Bulimia Nervosa (see p. 785for suggested research criteria).

Binge-Eating DisorderResearch criteria for binge eating disorderA. Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of bingeeating is characterized by both of the following:1. eating, in a discrete period of time1(eg, within any 2-hour

period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than mostpeople would eat in a similar period of time under similarcircumstances2. a sense of lack of control over eating during the episode

(eg, a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what orhow much one is eating)B. The binge-eating episodes are associated with three (ormore) of the following:1. eating much more rapidly than normal2. eating until feeling uncomfortably full3. eating large amounts of food when not feeling physically

hungry4. eating alone because of being embarrassed by how much

one is eating5. feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or very guilty

after overeatingC. Marked distress regarding binge eating is present.D. The binge eating occurs, on average, at least 2 days1 aweek for 6 months.E. The binge eating is not associated with the regular use of

inappropriate compensatory behaviors (eg, purging, fasting,excessive exercise) and does not occur exclusively during thecourse of Anorexia Nervosa or Bulimia Nervosa.

FIG: Diagnostic criteria for eating disorders. Reprinted with permission. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition, TR. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000 (10). 1Method of determining

frequency differs from that used for bulimia nervosa; future research should address whether counting the number of days on

which binges occur or the number of episodes of binge eating is the preferred method of setting a frequency threshold.

-

8/11/2019 85--ADATranstornosAlimentares

7/10816/ July 2001 Volume 101 Number 7

...................................................................................................................................................

ADA REPORTS

normalized eating plan and the elimination of binging. Helpingpatients combat food myths often requires specialized nutri-

tion knowledge. The registered dietitian is uniquely qualifiedto provide scientific nutrition education (62). Given that thereare so many fad diets and fallacies about nutrition, it is not

uncommon for other members of the treatment team to be

confused by the nutrition fallacies. Whenever possible, it issuggested that either formal or informal basic nutrition educa-

tion inservices be provided for the treatment team.Cognitive-behavioral therapy is now a well-established treat-

ment modality for BN (15,63). A key component of the CBTprocess is nutrition education and dietary guidance. Meal

planning, assistance with a regular pattern of eating, andrationale for and discouragement of dieting are all included inCBT. Nutrition education consists of teaching about body

weight regulation, energy balance, effects of starvation, mis-conceptions about dieting and weight control and the physicalconsequences of purging behavior. Meal planning consists ofthree meals a day, with one to three snacks per day prescribed

in a structured fashion to help break the chaotic eating pattern

that continues the cycle of binging and purging. Caloric intakeshould initially be based on the maintenance of weight to helpprevent hunger since hunger has been shown to substantiallyincrease the susceptibility to binging. One of the hardestchallenges of normalizing the eating pattern of the person with

BN is to expand the diet to include the patients self-imposedforbidden or feared foods. CBT provides a structure to planfor and expose patients to these foods from least feared to most

feared, while in a safe, structured, supportive environment.This step is critical in breaking the all or none behavior thatgoes along with the deprive-binge cycle.

Discontinuing purging and normalizing eating patterns are akey focus of treatment. Once accomplished, the patient isfaced with fluid retention and needs much education andunderstanding of this temporary, yet disturbing phenomenon.

Education consists of information about the length of time toexpect the fluid retention and information on calorie conver-sion to body mass to provide evidence that the weight gain is

not causing body mass gain. In some cases, utilization ofskinfold measurements to determine percent body fat may behelpful in determining body composition changes. The patientmust also be taught that continual purging or other methods of

dehydration such as restricting sodium, or using diuretics orlaxatives will prolong the fluid retention.

If the patient is laxative dependent, it is important to under-

stand the protocol for laxative withdrawal to prevent bowelobstruction. The registered dietitian plays a key role in helpingthe patient eat a high fiber diet with adequate fluids while the

physician monitors the slow withdrawal of laxatives and pre-

scribes a stool softener.A food record can be a useful tool in helping to normalize the

patients intake. Based on the patients medical, psychological

and cognitive status, food records can be individualized withcolumns looking at the patients thoughts and reactions toeating/not eating to gather more information and to educate

the patient on the antecedents of her/his behavior. The regis-tered dietitian is the expert in explaining to a patient how tokeep a food record, reviewing food records and understandingand explaining weight changes. Other members of the team

may not be as sensitive to the fear of food recording or asfamiliar with strategies for reviewing the record as the regis-tered dietitian. The registered dietitian can determine whether

weight change is due to a fluid shift or a change in body mass.

Medication management is more effective in treating BNthan in AN and especially with patients who present with

comorbid conditions (11,62). Current evidence cites com-bined medication management and CBT as most effective intreating BN, (64) although research continues to look at the

effectiveness of other methods and combinations of methods

of treatment.

EATING DISORDERS NOT OTHERWISE SPECIFIED(EDNOS)The large group of patients who present with EDNOS consistsof subacute cases of AN or BN. The nature and intensity of the

medical and nutritional problems and the most effective treat-ment modality will depend on the severity of impairment andthe symptoms. These patients may have met all criteria for

anorexia except that they have not missed three consecutivemenstrual periods. Or, they may be of normal weight and purgewithout binging. Although the patient may not present withmedical complications, they do often present with medical

concerns.

EDNOS also includes Binge Eating Disorder (BED) which islisted separately in the appendix section of the DSM IV(See Figure) in which the patient has binging behavior withoutthe compensatory purging seen in Bulimia Nervosa. It is esti-mated that prevalence of this disorder is 1 to 2% of the

population. Binge episodes must occur at least twice a weekand have occurred for at least 6 months. Most patients diag-nosed with BED are overweight and suffer the same medical

problems faced by the nonbinging obese population such asdiabetes, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol levels,gallbladder disease, heart disease and certain types of cancer.

The patient with binge eating disorder often presents withweight management concerns rather than eating disorderconcerns. Although researchers are still trying to find thetreatment that is the most helpful in controlling binge eating

disorder, many treatment manuals exist utilizing the CBTmodel shown effective for Bulimia Nervosa. Whether weightloss should occur simultaneously with CBT or after a period of

more stable, consistent eating is still being investigated(65,66,67)

In a primary care setting, it is the registered dietitian whooften recognizes the underlying eating disorder before other

members of the team who may resist a change of focus if theoverall objective for the patient is weight loss. It is then theregistered dietitian who must convince the primary care team

and the patient to modify the treatment plan to include treat-ment of the eating disorder.

THE ADOLESCENT PATIENT

Eating disorders rank as the third most common chronic illnessin adolescent females, with an incidence of up to 5%. Theprevalence has increased dramatically over the past three

decades (5,7). Large numbers of adolescents who have disor-dered eating do not meet the strict DSM-IV-TR criteria foreither AN or BN but can be classified as EDNOS. In one study,

(68) more than half of the adolescents evaluated for eatingdisorders had subclinical disease but suffered a similar degreeof psychological distress as those who met strict diagnosticcriteria. Diagnostic criteria for eating disorders such as DSM-

IV-TR may not be entirely applicable to adolescents. The widevariability in the rate, timing and magnitude of both height andweight gain during normal puberty, the absence of menstrual

periods in early puberty along with the unpredictability of

-

8/11/2019 85--ADATranstornosAlimentares

8/10

...................................................................................................................................................

Journal of THE AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION /817

ADA REPORTS

menses soon after menarche, and the lack of abstract concepts,limit the application of diagnostic criteria to adolescents

(5,69,70).Because of the potentially irreversible effects of an eating

disorder on physical and emotional growth and development in

adolescents, the onset and intensity of the intervention in

adolescents should be lower than adults. Medical complica-tions in adolescents that are potentially irreversible include:

growth retardation if the disorder occurs before closure of theepiphyses, pubertal delay or arrest, and impaired acquisition ofpeak bone mass during the second decade of life, increasingthe risk of osteoporosis in adulthood (7,69).

Adolescents with eating disorders require evaluation andtreatment focused on biological, psychological, family, andsocial features of these complex, chronic health conditions.

The expertise and dedication of the members of a treatmentteam who work specifically with adolescents and their familiesare more important than the particular treatment setting. Infact, traditional settings such as a general psychiatric ward may

be less appropriate than an adolescent medical unit. Smooth

transition from inpatient to outpatient care can be facilitatedby an interdisciplinary team that provides continuity of care ina comprehensive, coordinated, developmentally oriented man-ner. Adolescent health care specialists need to be familiar withworking not only with the patient, but also with the family,

school, coaches, and other agencies or individuals who areimportant influences on healthy adolescent development (1,7).

In addition to having skills and knowledge in the area of

eating disorders, the registered dietitian working with adoles-cents needs skills and knowledge in the areas of adolescentgrowth and development, adolescent interviewing, special

nutritional needs of adolescents, cognitive development inadolescents, and family dynamics (71). Since many patientswith eating disorders have a fear of eating in front of others, itcan be difficult for the patient to achieve adequate intake from

meals at school. Since school is a major element in the life ofadolescents, dietitians need to be able to help adolescents andtheir families work within the system to achieve a healthy and

varied nutrition intake. The registered dietitian needs to beable to provide MNT to the adolescent as an individual but alsowork with the family while maintaining the confidentiality ofthe adolescent. In working with the family of an adolescent, it

is important to remember that the adolescent is the patient andthat all therapy should be planned on an individual basis.Parents can be included for general nutrition education with

the adolescent present. It is often helpful to have the RD meetwith adolescent patients and their parents to provide nutritioneducation and to clarify and answer questions. Parents are

often frightened and want a quick fix. Educating the parents

regarding the stages of the nutrition plan as well as explainingthe hospitalization criteria may be helpful.

There is limited research in the long-term outcomes of

adolescents with eating disorders. There appear to be limitedprognostic indicators to predict outcome (3,5,72). Generally,poor prognosis has been reported when adolescent patients

have been treated almost exclusively by mental health careprofessionals (3,5). Data from treatment programs based inadolescent medicine show more favorable outcomes. Reviewsby Kriepe and colleagues (3, 5, 73) showed a 71 to 86%

satisfactory outcome when treated in adolescent-based pro-grams. Strober and colleagues (72) conducted a long-termprospective follow-up of severe AN patients admitted to the

hospital. At follow-up, results showed that nearly 76% of the

cohort meet criteria for full recovery. In this study, approxi-mately 30% of patients had relapses following hospital dis-

charge. The authors also noted that the time to recoveryranged from 57 to 79 months.

POPULATIONS AT HIGH RISK

Specific population groups who focus on food or thinness suchas athletes, models, culinary professionals, and young people

who may be required to limit their food intake because of adisease state, are at risk for developing an eating disorder (21).Additionally, risks for developing an eating disorder may stemfrom predisposing factors such as a family history of mood,

anxiety or substance abuse disorders. A family history of aneating disorder or obesity, and precipitating factors such as thedynamic interactions among family members and societal pres-

sures to be thin are additional risk factors (74,75).The prevalence of formally diagnosable AN and BN in males

is accepted to be from 5 to 10% of all patients with an eatingdisorder (76,77). Young men who develop AN are usually

members of subgroups (eg, athletes, dancers, models/per-

formers) that emphasize weight loss. The male anorexic ismore likely to have been obese before the onset of the symp-toms. Dieting may have been in response to past teasing orcriticisms about his weight. Additionally, the association be-tween dieting and sports activity is stronger among males.

Both a dietary and activity history should be taken with specialemphasis on body image, performance, and sports participa-tion on the part of the male patient. These same young men

should be screened for androgenic steroid use. The DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criterion for AN of

-

8/11/2019 85--ADATranstornosAlimentares

9/10818/ July 2001 Volume 101 Number 7

...................................................................................................................................................

ADA REPORTS

References1. Adolescent Medicine Committee, Canadian Paediatric Society. Eating

Disorders in adolescents: Principles of diagnosis and treatment. Paediatrics

and Child Health.1998;3(3):189-92.

2. Rock, CL. Nutritional and medical assessment and management of eating

disorders. Nutr Clin Care. 1999;2:332-343.

3. Kreipe RE, Uphoff M. Treatment and outcome of adolescents with anor-

exia nervosa. Adolesc Med.1992;16:519-540.

4. Gralen SJ, Levin MP, Smolak L et al. Dieting and disordered eating during

early and middle adolescents: Do the influences remain the same? Int J

Eating Disorder.1990;9:501-512.

5. Kreipe RE, Birndorf DO. Eating disorders in adolescents and young

adults. Medical Clinics of North America. 2000;84(4):1027-1049.

6. Becker AE, Grinspoon SK, Klibanski A, Herzog DB. Eating Disorders. New

England J Med. 1999;340(14):1092-1098.

7. Fisher M, Golden NH, Datzman KD, Kreipe RE, Rees J, Schebendach J,

Sigman G, Ammerman S, Hoberman HM. Eating disorders in adolescents: a

background paper. J Adol Health Care.1995;16:420-437.

8. Kreipe RE, Churchill BH, Strauss J. Longer-term outcome of adolescent

with anorexia nervosa. Am J Dis Child1989;43:1233-1327.

9. Rogers L, Resnick MD, Mitchell JE, Blum RW. The relationship between

socioeconomic status and eating-disordered behaviors in a community

sample of adolescent girls. Intern J Eating Disorders.22(10):15-23.1997.

10. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual for

mental disorders (fourth edition, text revision). APA Press: Washington DC;

2000.

11. Halmi KA. Treatment of anorexia nervosa: a discussion. J Adolesc Health

Care. 1983;4:47-50.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the treatment

of patients with eating disorders. Am J Psych.2000;157 (suppl):1-39.

13. Dansky BS, Brewerton TD, Kilpatrick DG, ONeil PM. The National

Womens Study: relationship of victimization and posttraumatic stress disor-

der to bulimia nervosa. Int J Eating Disorder. 1997;21:213-228.

14. Steiner H. Mazer C, Litt, IF. Compliance and outcome in anorexia

nervosa. West J Med.1990;153:133-139.

15. Wilson GT. Cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorder: progress and

problems. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1999;37(suppl 1):S79-95.

16. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to

Change Addictive Behavior.New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1991.

17. Prochaska, J, Norcross, J. DiClemente, C. Changing for Good. New York,

NY: William Morrow and Company; 1994.

18. Prochaska J, Johnson S, Lee P. The Transtheoretical model of behavior

change. In Shumaker SA, Schron EB, Ockene J, McBee WL, editors. The

Handbook of Health Behavior Change. New York: Springer Publishing Com-

pany; 1998:5-32.

19. Ressler A. A body to die for:Eating disorders and body-image distortion

in women. Int J Fertility and Womens Medicine. 1998;43(3):133-138.

20. Portilla MG, Smith PD. Diagnosis and treatment of adolescents with

eating disorders. J Arkansas Med Society. 1997;94(5):211-214.

21. Engstrom I, Kroon M, Arvidson CG, Segnestam K, Snellman K, Aman J.

Eating disorders in adolescent girls with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus:

a population-based case-control study. Acta Paediatrica. 1999;88(2):175-

180.

22. Executive Summary of the Clinical Guidelines on the Identification,

Evaluation and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Arch Intern

Med. 1998;158:1855-1867.

23. CDC growth charts. Available at: www.cdc.gov/growthcharts. 2000.

24. Nudel DB, Gootman N, Nussbaum MP, Shenker IR. Altered exercise

performance in patients with anorexia nervosa. J Pediatrics. 1984;105:34-42.

25. Schebendach J, Reichert-Anderson P. Nutrition in Eating Disorders. In:

Krauss Nutrition and Diet Therapy.Mahan K, Escott-Stump S (eds). McGraw-

Hill: New York, NY; 2000.

26. Swenne I. Heart risk associated with weight loss in anorexia nervosa and

eating disorders: electrocardiographic changes during the early phase of

refeeding. Acta Paediatr. 2000;89:447-452.

27. Harris JP, Kriepe RE, Rossback CN. QT prolongation by isoproterenol in

anorexia nervosa. J Adol Health. 1993;14:390-393.

28. Cooke RA, Chambers JB. Anorexia nervosa and the heart. Br J Hosp

Med. 1995;54:313-317.

29. Silber T. Anorexia nervosa: Morbidiy and mortality. Ped Ann.1984;

13:851-859.

30. Web JC, Kiess, MS, Chan-Yan CC. Malnutrition and the heart. Can Med

Assoc J. 1986;135:753-758.

31. Katzman DK, Zipursky RB. Adolescents with anorexia nervosa: The

impact of the disorder on bones and brains. In: Adolescent nutritional

disorders: prevention and treatment.Jacobson MS, Rees JM, Golden NH,

and Irwin CE (eds).Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. New York,

NY 1997;817:127-137.

32. Dolan RJ, Mitchell JA. Structural brain changes in patients with anorexia

nervosa. Psychiatr Med.1988;18:349-353.

33. Artmann H, Gruau H, Adelmann M. Reversible and non-reversible en-

largement of cerebrospinal fluid spaces in anorexia nervosa. Neuoradiology.

1985;27:304-312.

34. Nusabum M, Shenker I, Marc J et al. Cerebral atrophy in anorexia

nervosa. J Pediatr. 1980;96:869-876.

35. Fisher M. Medical complications of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Adol

Med Stat of the Art Reviews.1992;3:481-502.

36. Bachrach LK, Guido D, Datzman et al. Decreased bone density in

adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. Pediatrics.1990;86:440-447.

37. Biller BMK, Saxe V, Herzog DB, et al. Mechanisms of osteoporosis in

adult and adolescent women with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Edocrinol Metab.

1989;68:548-554.

38. Bachrach LK, Katzman DK, Litt JF, Buido D, Marcus R. Recovery from

osteopenia in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab. 1991;72:602-606.

39. Carmichael KA, Carmichael DI. Bone metabolism and osteopenia in

eating disorders. Medicine.1995;74:254-267.

40. Robinson E, Bachrach KL, Katzman DK. Use of hormone replacement

therapy to reduce the risk of osteopenia in adolescent girls with anorexia

nervosa. J Adol Health. 2000;26:343-348.

41. Harcoff D. Pathological consequences of eating disorders. Childrens

Hospital Quarterly.1982;3:17-21.

42. Devuyst O, Lambert M, Rodhain J, Lefebvre C, Coche E. Hematological

changes and infectious complication in anorexia nervosa: a case control

study Q J M. 1993;86:791-799.

43. Pomeroy C, Mitchell JE, Eckert ED. Risk of infection and immune function

in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eating Disorder.1992;12:47-55.

44. Arden MR, Weiselbert EC, Nussbaum MP, Shenker IR, Jacobson MS, et

al. Effect of weight restoration on the dyslipoproteinemia of anorexia nervosa.

J Adol Health. 1990;11:199-202 .

45. Sargent J, Liebman R. Outpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa. Psycho-

somatics. 1984;7:235-245.

combination of self-study, continuing education programs andsupervision by another experienced registered dietitian and/or

an eating disorder therapist. Knowledge and practice usingmotivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral therapywill enhance the effectiveness of counseling this population.

Practice groups of the American Dietetic Association such as

Sports, Cardiovascular, and Sports Nutrition (SCAN) and thePediatric Nutrition Practice Group (PNPG) as well as other

eating disorders organizations such as the Academy of EatingDisorders and the International Association of Eating DisorderProfessionals provide workshops, newsletters and conferenceswhich are helpful for the registered dietitian.

-

8/11/2019 85--ADATranstornosAlimentares

10/10

...................................................................................................................................................

Journal of THE AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION / 819

ADA REPORTS

46. Durnin JVGA, Rahaman MM. The assessment of the amount of body fat

in the human body from measurements of skinfold thickness. Br J Nutr. 1967;

21:681-685.

47. Durnin JVGA, Wormersley J. Body fat assessed from total body density

and its estimation from skinfolds thickness: Measurements of 481 men and

women aged from 16-72 years. Br J Nutr.1974;32:77-82.

48. Probst M. Body composition in female anorexia nervosa patients. Br J

Nutr.1996;76:639-644.

49. Birmingham CL. The reliability of bioelectrical impedance analysis for

measuring changes in the body composition of patients with anorexia

nervosa. Int J Eating Disord. 1996;19:311-313.

50. Scalfi L. Bioimpediance and resting energy expenditure in undernour-

ished and refed anorectic patients. Eur J Clin Nutr1993;47:61-68.

51. Solomon SM, Kirby DF. The refeeding syndrome: A review. J Parenteral

Enter Nutr. 1990;14:90-97.

52. Feldman, R. Refeeding the malnourished patient. In: Sieisenger and

Fordtrans Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease,6th ed. WB Saunders Com-

pany, New York, NY; 1998.

53. Powers PS, Powers HP. Inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa. Psycho-

somatics.1984;25:512-545.

54. Larocia FEF. An inpatient model for the treatment of eating disorders.

Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1984;7:287-298.

55. Hudson JI, Pope HG. The Psychobiology of Bulimia. Washington DC:

American Psychiatric Press; 1987.

56. Kirkley BG. Bulimia: Clinical characteristics, development and etiology.

J Am Diet Assoc. 1986;86:468-475.

57. Heatherington MM, Altemus M, Nelson ML. Eating behavior in bulimia

nervosa: multiple meal analyses. Amer J Clin Nutr. 1994;60:864-873.

58. Haiman C, Devlin MJ. Binge eating before the onset of dieting: a distinct

subgroup of bulimia nervosa. Int J Eating Disorders. 1999;25:151-157.

59. Mitchell JE, Hatsukami D, Eckert ED, Pyle RL. Characteristics of 275

patients with bulimia. Am J Psych. 1985;142:482-485.

60. Kaye WH, Weltzin TE, Hsu LK, McConaha CW, Bolton B. Amount of

calories retained after binge eating and vomiting. Amer J Psych. 1993;

150:969-971.

61. BoLinn GW, Morawski SG, Fordtran JS. Purging and calorie absorption

in bulimic patients and normal women. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:14-17.

62. Boardley D. The Treatment of Eating Disorders: Role of the Dietitian. In:

Garner DM ed. Academy for Eating Disorders Newsletter. Winter 2000;1-4.

63. Fairburn CG, Jones R, Peveler RC, Hope RA, OConnor M. Psycho-

therapy and bulimia nervosa: longer-term effects of interpersonal

psychotherapy, behavior therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy. Arch

Gen Psych.1993;50:419-428.

64. Jimmerson, DC, Wolfe BE, Brotman AW, Metzer ED. Medications in the

treatment of eating disorders. Psych Clin North America. 1996;19:739-754.

65. Grilo CM. The Assessment and Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder.

Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health.1998;4:191-201.

66. Williamson DA, Martin CK. Binge eating disorder: A review of the

literature after publication of the DSM-IV. Eating and Weight Disorders:

Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity. 1999;4(3):103-114.

67. Goldfein JA, Devlin JH. Spitzer RL. Cognitive behavioral therapy for the

treatment of binge eating disorder: what constitutes success. Am J Psychia-

try. 2000;157(7):1051-1056.

68. Bunnell DW, Shenker IR, Nussbaum MP, Arden MR, Jacobson MS.

Subclinical versus formal eating disorders: Differentiating psychological

features. Int J Eating Disorder.1990;9:357-362.

69. Abrams SA, Silber TJ, Esteban NV. Mineral balance and bone turnover

in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Pediatr. 1993;123:326-331.

70. Pfeiffer RJ, Lucas AR, Illstrup DM. Effect of anorexia nervosa on linear

growth. Clin Pediatr. 1986;25:7-12.

71. Levin MP, Smolak L, Moody AF. Normative developmental challenges

and dietitian and eating disturbances in middle school girls. Int J Eating

Disord. 1994;15:11-20.

72. Strober M, Freeman R, Morrell W. The long-term course of severe

anorexia nervosa in adolescents: Survival analysis of recovery, relapse and

outcome predictors over 10-15 years in a prospective study. Int J Eat Disord.

1997;22:339-369.

73. Kreipe RE, Durkarm CP. Outcome of anorexia nervosa related to treat-

ment utilizing an adolescent medicine approach. J Youth Adolescence.

1996;25:483-397.

74. Woodside DB, Field LL, Garfinkel PE, Heinman M. Specificity of eating

disorders diagnoses in families of probands with anorexia nervosa and

bulimia nervosa. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1998;39(5):261-264.

75. Garner DM. Garfinkle PE. Handbook of Treatment of Eating Disorders,

2nd ed. New York NY: Guilford Press; 1997.

76. Farrow JA. The adolescent male with an eating disorder. Pedia Ann.

1992; 21:769-773.

77. Carlat DJ, Camargo CA, Herzog DB. Eat ing Disorders in Males: A reporton 135 patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(8):1127-1132.

78. Braun D. Sunday SR, Huang A, Halmi KA. More males seek treatment for

eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25(4):415-424.

79. Halmi KA, Sunday, SR. Temporal patterns of hunger and fullness ratings

and related cognitions in anorexia and bulimia. Appetite. 1991;16(3):219-37.

80. Sunday SR, Halmi KA. Eating Behavior and Eating Disorders: the inter-

face between clinical research and clinical practice. Psychopharmacology

Bulletin. 1997;33(3):373-379.

81. Nakai Y, Koh T. Perception of Hunger to Insulin-Induced Hypoglycemia

in Anorexia Nervosa. Int J Eat Dis. 2001;29(3):354-357.

ADA position adopted by the House of Delegates on October18, 1987 and reaffirmed on September 12, 1992 and on Sep-tember 28, 1998. The update will be in effect until December

31, 2005. The American Dietetic Association authorizes repub-lication of the position, in its entirety, provided full and propercredit is given. Requests to use portions of this position must

be directed to ADA Headquarters at 800/877-1600, ext. 4835 [email protected].

Recognition is given to the following for their contributions:Authors:Bonnie A. Spear, PhD, RD (University of Alabama at Birming-ham, Dept. of Pediatrics, Birmingham, AL) and Eileen Stellefson

Myers, MPH, RD, FADA (Marketing, Discovery Alliance Inter-national, Charleston, SC)

Reviewers:Joy Armillay, EdD, RD (New Hope of Pennsylvania, Kingston,PA);

Academy for Eating DisordersLeah L. Graves, RD, LD

(Laureate Psychiatric Hospital, Tulsa, OK; Tami J. Lyon, MPH,RD, CDE (Healthy Living, San Francisco, CA); Marsha D.Marcus, PhD (University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine,

Western Psychiatric Institute, Pittsburgh, PA); Joel Yager, MD(University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque,NM);

Dietetics in Development & Psychiatric Disorders dietetic

practice groupKaren D. Blachley, RD; (Betty Ford Center,Rancho Mirage, CA);Betsy Friedman, MSW, RD (Private Practice, Glastonbury,

CT);Pediatric Nutrition dietetic practice groupDiana MarieSpillman, PhD, RD, LD (Miami University, Oxford, OH);

Sports, Cardiovascular, and Wellness Nutritionist dieteticpractice groupKaren Kratina, MA, RD (Consultant,Gainesville, FL)

Members of the Association Positions Committee Workgroup:Ethan Bergman, PhD, RD, CD; Joan Heins, MA, RD; NancyWooldrige, MS, RD; Lisa Marie Varnert, PhD, RD (content

advisor)